Why Dreaming Big Can Be a Huge Waste of Time And Money

Pathological technology is technology motivated by emotions not reason, says author.

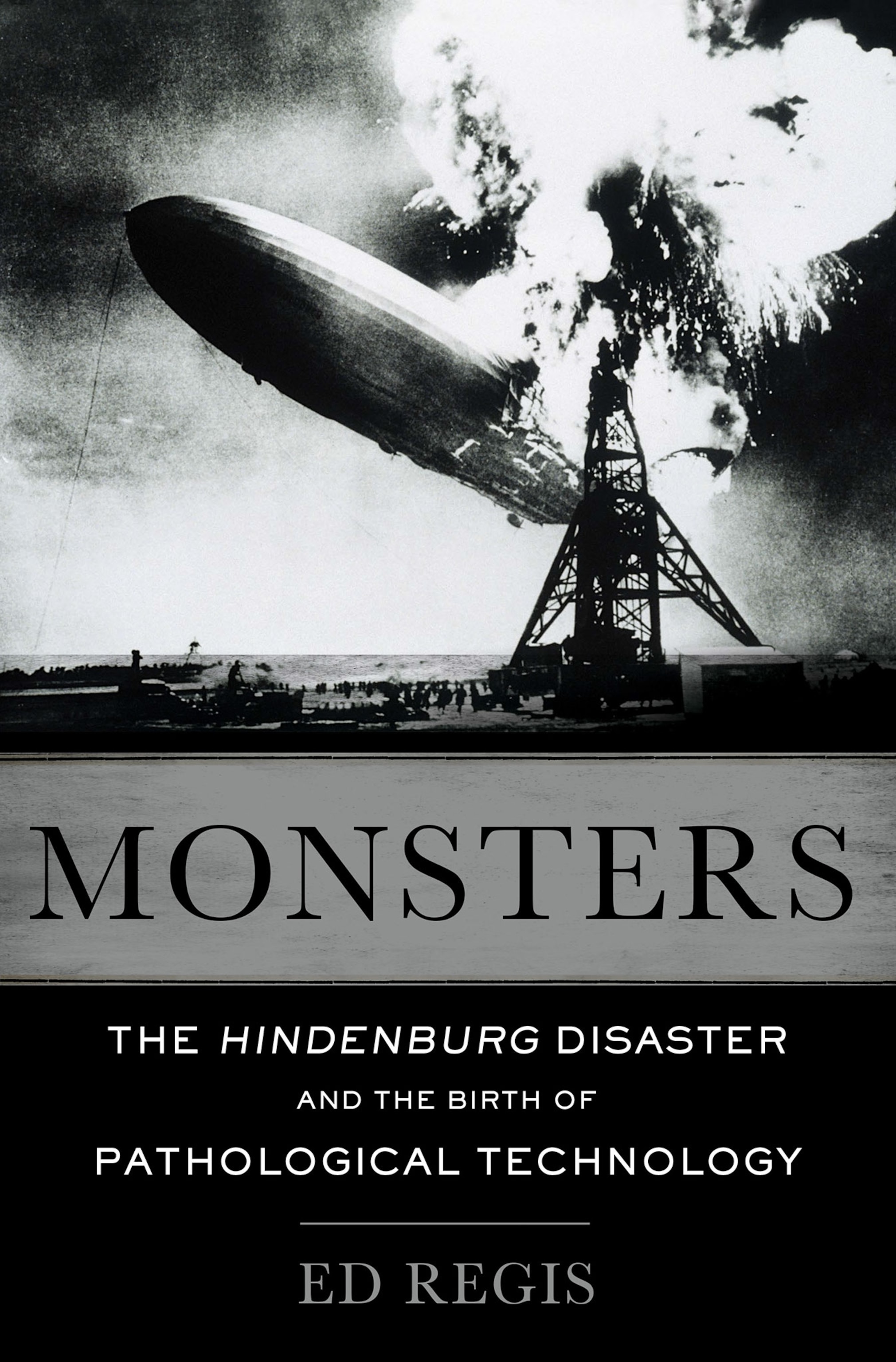

“Oh, the humanity!” was the cry from radio announcer Herbert Morrison on May 6, 1937, as the LZ 129 Hindenburg zeppelin burst into flames over Lakehurst, New Jersey.

Morrison's breathless description sent news of the disaster around the world in a real-time recording that would become one of the most famous audio reports ever filed.

Starting with eyewitness accounts and in-depth analysis of the zeppelin catastrophe, Ed Regis, author of The Hindenburg Disaster and The Birth of Pathological Technology, also tells the story of other mega-projects that were inherently flawed and often dangerous but which, despite their astronomical cost, became reality.

Speaking from his home in Frederick County, Maryland, he explains how Hollywood got it wrong about the Hindenburg disaster, why a giant hole in the ground in Texas cost the U.S. taxpayer six billion dollars, and why he thinks the idea of interstellar travel is not romantic—but idiotic.

We’re brought up to believe in technological progress. You have a very different view, don’t you? Explain what you mean by “pathological technologies.”

I’m all in favor of technological progress, but it has to be motivated by rational, real-life concerns. Pathological technology is technology that’s motivated more by emotions. In some cases it’s almost exclusively driven by emotion rather than reason. The best example of this is the Hindenburg, which went up in flames in New Jersey in May 1937.

What a lot of people don’t realize is that 26 prior Zeppelins also burst into flames, crashed, and killed people, including some British hydrogen airships. What is the emotion in this case? It has to do with size. The Hindenburg was longer than the Capitol building. To see this cosmic, manmade object drove the Germans into a frenzy, not because it enabled people to travel. It only carried a few dozen people at most. It was motivated by this awesome sight in the sky.

The book starts with the Hindenburg disaster. Set the scene for us.

The airship was approaching its mooring mast in Lakehurst toward evening. Everything seemed to be going smoothly, like an ocean liner coming in to dock. Then all of a sudden, it burst into flames, and it was gone from the face of the Earth, with the exception of its metal skeleton and a few other remnants, in the space of 34 seconds.

All of a sudden, it burst into flames and was gone from the face of the Earth.Ed Regis

The reason it happened so quickly was that the ship was filled with seven million cubic feet of hydrogen gas, a highly flammable and indeed explosive gas, when mixed with air. Some hydrogen had escaped from one of the gas cells inside the Hindenburg and was ignited by static electricity caused by lightning. As hydrogen streamed out of the Hindenburg, it mixed with air and ignited.

Amazingly, although there were 97 people on board, only 35 died. If you look at the videos on YouTube, you’d think this had to be a non-survivable accident. But the vast majority of the passengers and crew survived.

Thanks to a project called Faces Of The Hindenburg, we know a lot about the people on board. Pluck out a few particularly interesting ones for us.

It’s hard to talk about these because I got pretty emotionally involved with them. [Sighs] The Doehners were a family of five: Walter Doehner and his wife, Matilda, and the three children, Walter, Werner, and Irene. The father and mother were on the deck promenade, looking out at the scene as the Hindenburg came in to land. The father then went downstairs to get a roll of film, and perished in the accident.

The mother jumped out and survived. Before she did so, she threw out her two little boys, Walter and Werner, aged ten and eight, respectively. That left the girl, Irene. She was rescued by a tanker driver for the Esso oil company named Emil Hoff, who was there to refill the diesel fuel tanks. He actually went into the craft during this 34-second period, while the airship was aflame, and got her out. But she died during the night because she was so badly burned.

There were also two journalists on board, Leonard Adelt and his wife, Gertrud. Leonard cowrote a book called The Zeppelin, with one of the captains of the line. But although he survived the accident, he returned to Germany and was in the city of Dresden during the firebombing, so he died in flames in Dresden.

Radio announcer Herbert Morrison’s cry, “Oh, the humanity!” as he witnessed the disaster became instantly famous. This was also one of the first disasters to be filmed. How did this affect its cultural afterlife?

It put an end to airship mania, except in Germany. The Hindenburg had a sister ship, the LZ130, and when the Hindenburg disaster happened, they didn’t want to dismantle it. They thought they could fill it with helium, which is a non-flammable gas. But the United States held almost total control over helium supplies. The Helium Control Act of 1927 prohibited sale of helium to any foreign power, including Germany.

So although the Zeppelin company tried to get helium to inflate the sister ship, they weren’t able to do, so they went and filled it with hydrogen and even flew it over Germany, as if nothing had ever happened! Once again, it was the emotional appeal of this immense object, even though the Hindenburg disaster had shown it was actually a flying bomb.

Like 9/11, there were also many conspiracy theories about the Hindenburg. Give us an overview.

There’s one major conspiracy theory: that the fire was due to sabotage rather than electrical discharge. A movie was made called The Hindenburg, starring George C. Scott, which depicted the cause of the crash as sabotage. But there’s not a shred of evidence sabotage was involved. The FBI did a very thorough investigation of the one person considered a possible culprit, a guy by the name of Joseph Spah, an acrobat and anti-Nazi who was cracking jokes during the crossing from Frankfurt to New Jersey. People tried to attribute the disaster to him. But he had no real motive; he didn’t have the means; and there was no evidence.

The other wild theory is that the disaster was not the result of the hydrogen but rather due to the Hindenburg’s outer skin, which was painted with an exceptionally flammable compound. This theory was put forward by a former NASA scientist, Addison Bain. He didn’t offer much in the way of evidence, and the theory about is, in fact, preposterous. It’s worth noting that Bain is a proponent of hydrogen as a valuable new energy source, so he was trying to exonerate his pet project.

The real cause was a spark caused by an electrical storm that had passed through the area shortly before the Hindenburg tried to land. An electrical storm turns the surrounding atmosphere into a kind of atmospheric battery. At least one observer also noted that some of the outer fabric was flapping, as if air was rushing out from the interior. But there was no air inside the craft. So it must have been hydrogen coming out. The one thing that’s unexplained is where the leak came from. How come, all of a sudden, there was a leak of hydrogen gas, during the approach? That remains unexplained to this day.

Some of the projects you describe can consume vast sums of money. Tell us about the Superconducting Supercollider (SSC)

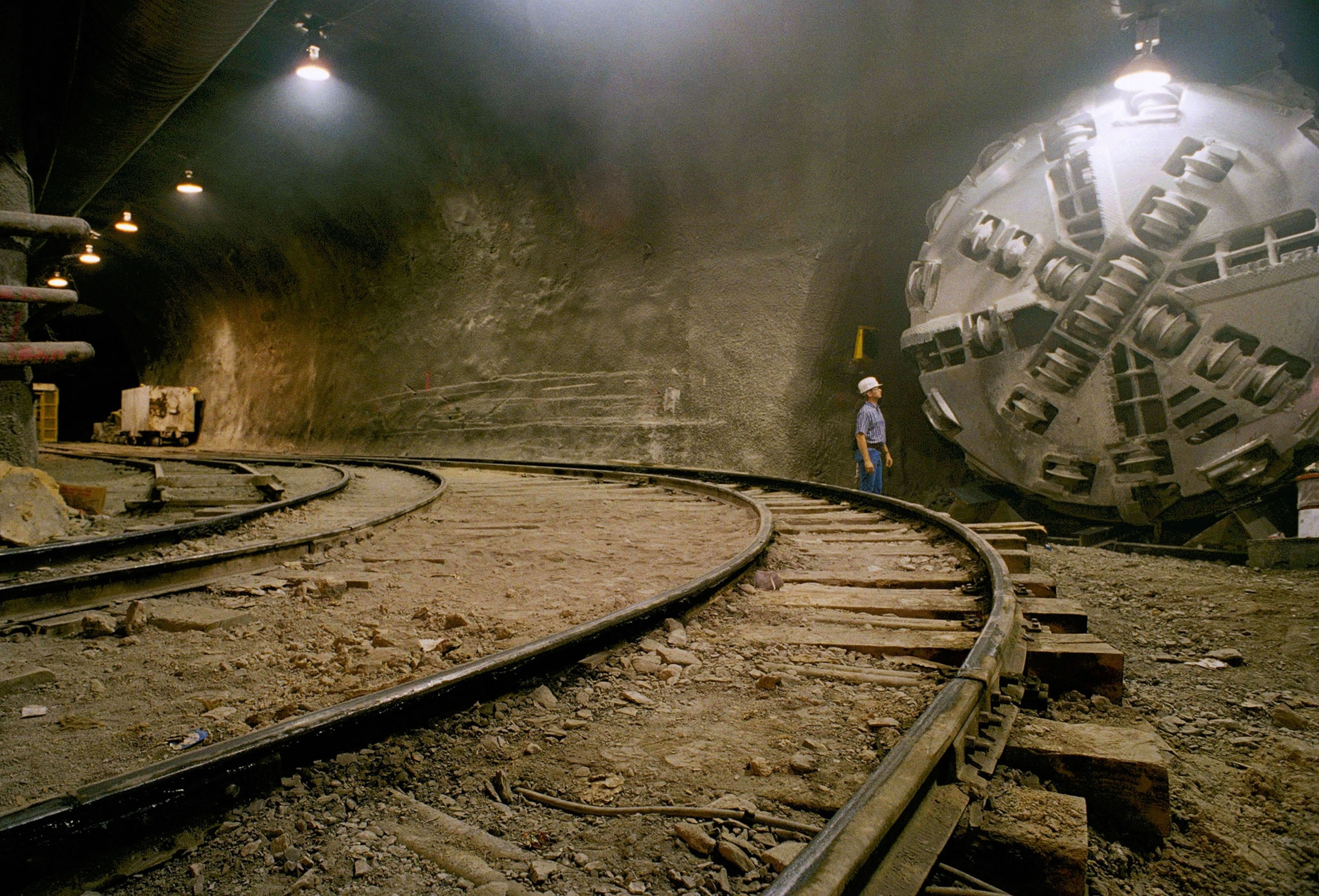

[Laughs] That’s one of my favorite examples, although people claim I’m being anti-science when I criticize it. The Superconducting Supercollider was proposed back in the ’80s. It was to be a 54-mile-long tunnel in Texas filled with superconducting magnets. To energize these, they had to be kept cold with liquid helium at about 400 degrees below zero. It was wildly expensive, not so much to dig the tunnel but to fill it with these superconducting magnets, cool them to 400 degrees below zero, and then keep them at that temperature while you’re doing your scientific experiment.

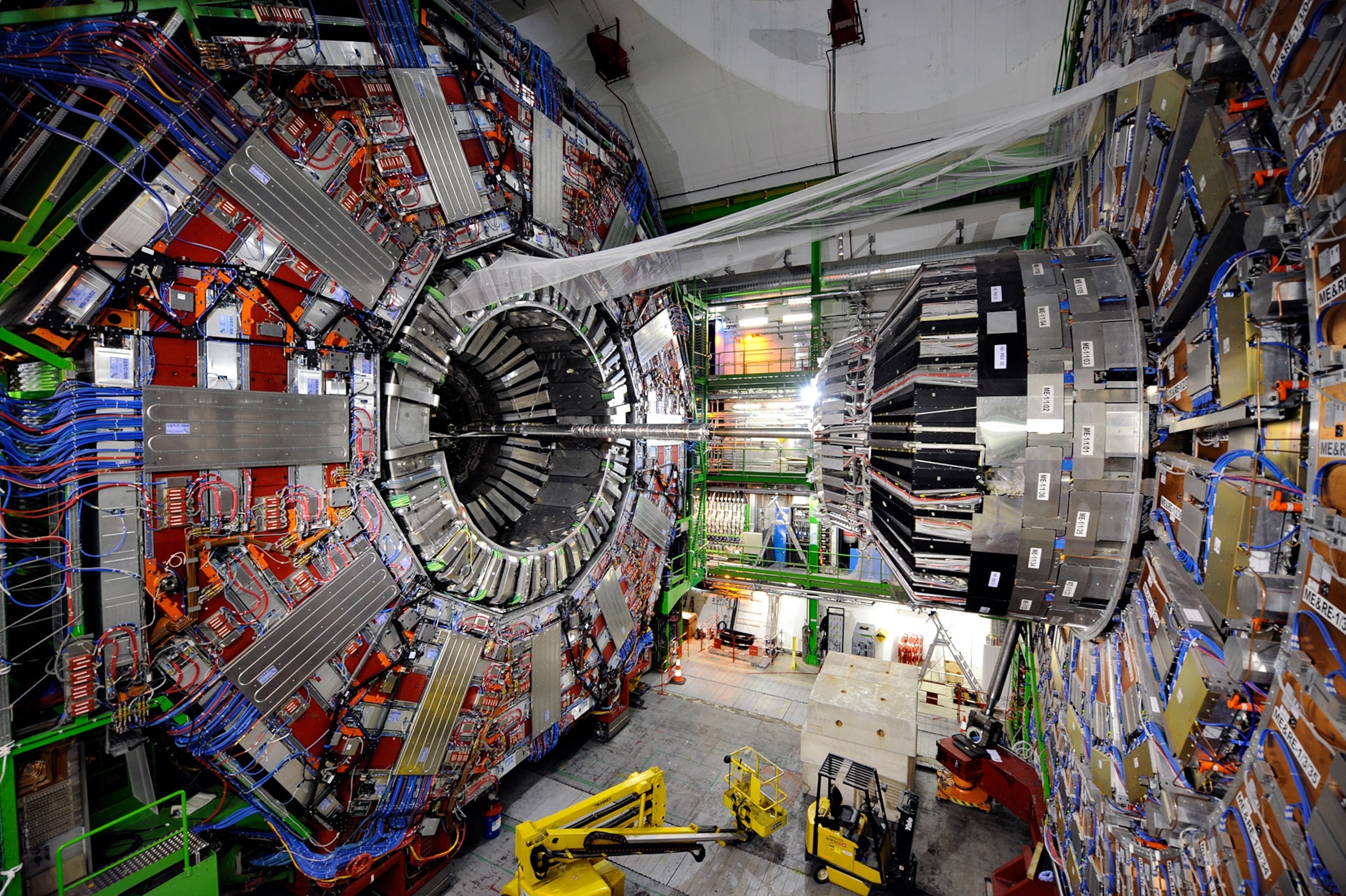

The purpose of the experiment was to find whether or not the Higgs-Boson particle existed. It was going to be like the Large Hadron Collider near Geneva, except that one is only 17 miles in diameter. The SSC was going to be more than three times bigger and would have taken billions and billions of dollars to construct.

The emotion involved here was to plumb the deepest secrets of nature. For particle physicists, the Higgs Boson is like the Holy Grail. They speak of it in religious terms, as though it’s their duty to gain this knowledge. My point is that some knowledge may be too expensive to gain.

Luckily, the SSC was stopped by Congress after about ten miles of tunnel and 17 access shafts had been dug and two magnets installed. It became a white elephant: a gigantic waste of five to six billion dollars to build a non-functional hole in the ground.

Man has long dreamed of interstellar travel. Tell us about the 100 Year Starship project—and why you think it’s a ludicrous idea.

[Laughs] The hundred-year starship project was instigated by DARPA, the Defence Advanced Research Projects Agency, which in 2010 offered $500,000 to any organization or individual who could put together a plan for building a starship that would take a founding colony of human beings to another solar system.

Now I’m not against the human colonization of space. My point is that we should do this incrementally. We could start with an orbiting space colony, or one on the moon. We could even start one on Mars, as Elon Musk wants to do.

I’m not against the human colonization of space.Ed Regis

But to go to another star system? We’re talking about stars that are so far away it’s almost inconceivable. Voyager recently exited the solar system and is traveling away from us at the speed of something in the neighborhood of 43,000 miles per hour. But if that craft were to go to the nearest star system, Proxima Centuri, which is four light-years away, it would still take 76,000 years.

There are much cheaper, closer ways of building colonies in space. There’s simply no point in going to the stars. People who want to do so are just enthralled by the idea of going to the stars. What more romantic phrase can you think of than “going to the stars”? It’s just wonderful! But to me it’s not wonderful at all. It’s just pretty idiotic. [Laughs]

Surely, if we stopped dreaming the impossible most of the great discoveries and achievements of the past 1,000 years would never have happened?

I don’t think people strive after the impossible. The advances that have been made were things we knew in advance were probably doable, but we didn’t have the means or technology and theories to achieve them. Take flight, for example. Birds fly, bees fly, so it’s been known since the beginning of time that flight was possible. Human flight was looked upon as impossible, but it was gradually achieved.

Most scientific and technological progress has been the result of incremental steps. I don’t buy the premise that progress through history was a result of trying to do the impossible. The point I’m making is not that you shouldn’t try to do things that sound impossible. You shouldn’t do things that are irrational, like the Hindenburg, or unnecessary, like the Superconducting Supercollider or interstellar flight. They’re achievable, but they’re pointless. They’re expensive, they harm the environment, they harm people, and there are other ways of accomplishing the same objective.

Simon Worrall curates Book Talk. Follow him on Twitter or at simonworrallauthor.com.