What we can learn from watching 100,000 animals in unbelievable detail—from space

By monitoring the movement, health, and environmental conditions of thousands of animals at once, Project ICARUS hopes to solve scientific mysteries.

A satellite recently ferried into space by a SpaceX rocket marks a crucial step toward tracking wildlife in unprecedented detail.

Project ICARUS (International Cooperation for Animal Research Using Space) will monitor thousands of animals, from mammals to insects, in real time. The November launch will be a test phase for a new, more nimble satellite developed after the program underwent a three-year hiatus. A second satellite will be launched in March in coordination with the National Geographic Society, with plans for more launches down the line.

Scientists working on the project say it will not only tell them more about animals’ movements, but also how these movements can help predict everything from the weather to disease spread.

“I think we need a new Earth observation system for life itself,” says Martin Wikelski, director at the Max Planck Institute of Animal Behavior in Germany and a National Geographic Explorer.

Wikelski is excited to find answers to the lengthy list of questions that have long vexed him, such as: What happened to the three billion songbirds that seem to have gone missing in North America? And what can animals sense that alerts them to an oncoming disaster?

Even more exciting, he says, are the answers to the questions he and his peers haven’t even thought to ask yet.

“We know it will provide amazing information,” he says.

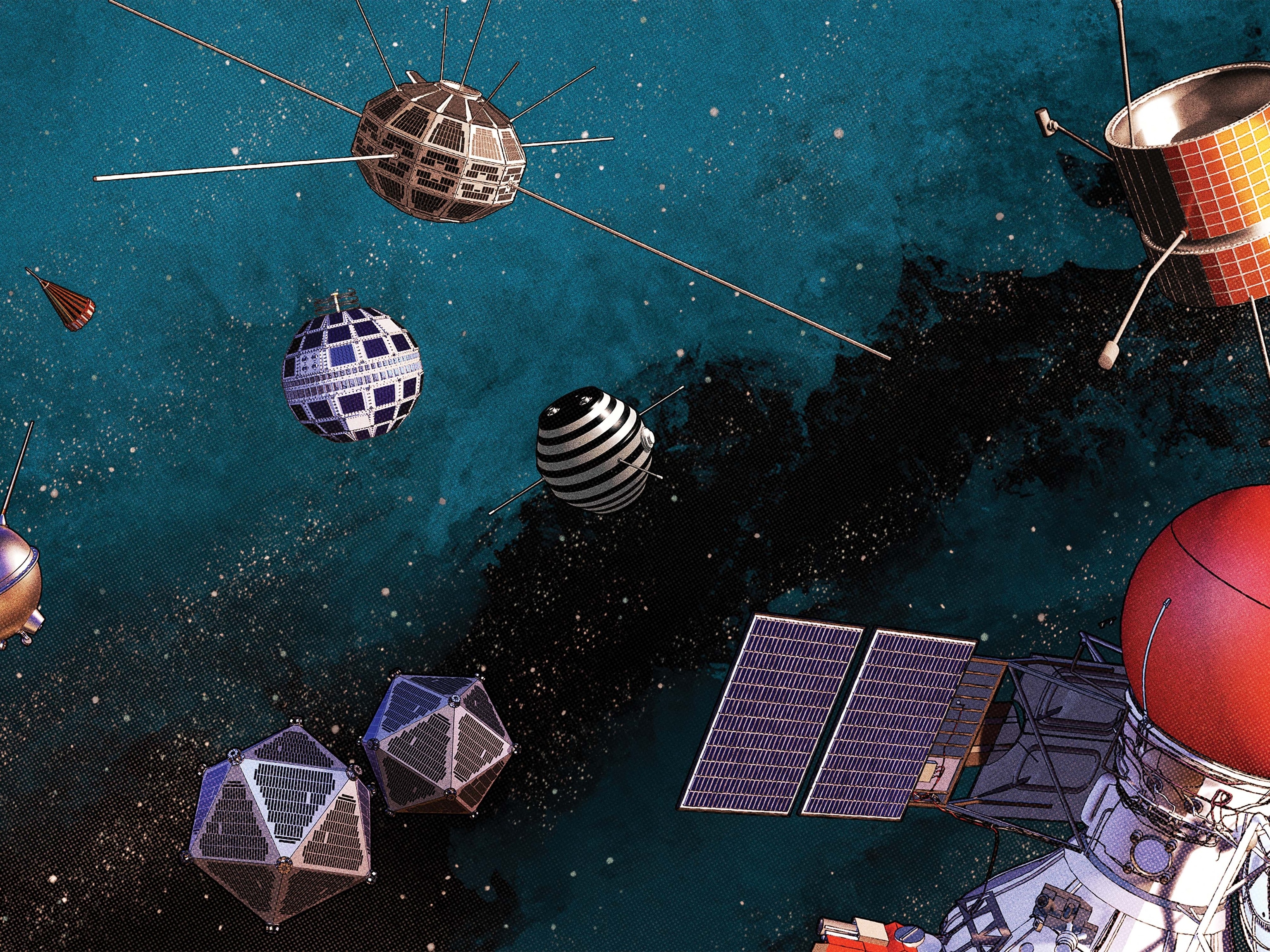

ICARUS 2.0 gets a lighter, more efficient upgrade

The first iteration of Project ICARUS took the form of an antenna abroad the International Space Station. Launched into space in 2020, it was a feat eight years in the making, says Wikelski. In just a year’s time, the antenna watched hundreds of animals from 15 different species. Scientists learned that Hudsonian godwits, a type of bird, can fly nonstop from Central America to Texas and that cuckoos, another bird, can fly over the Indian Ocean from India to Africa.

However, after Russia invaded Ukraine in 2022, Project ICARUS was paused when a collaborative space program between Germany and Russia ended.

“The war was horrible and still is, but in the end, it made our engineers work super hard on a new system,” he says.

“The antenna in the previous launch was a monster,” says Wikelski of its original size. The new ICARUS system measures just 10 centimeters long.

It’s now fitted on a box-shaped satellite—an aptly named CubeSat—that Wikelski describes as the size of a refrigerator (“a European fridge,” he clarifies). He says future satellites will be even smaller, around the size of a shoebox.

During this new satellite’s test period, Wikelski and his team will make sure the satellite orbits a viable path around the Earth and effectively connects to computers on the ground.

“It's almost like a line scanner. It goes pole to pole, scanning every corner of the earth roughly within a day,” says Wikelski.

If all goes as planned, his team plans to launch another National Geographic Society-funded satellite in the spring. By 2027, they plan to have six ICARUS satellites monitoring animals.

Then, he and his collaborators will begin the painstaking work of fitting new animals with small tags that send pings of data to the satellites in orbit.

How the project will monitor thousands of animals

The solar-powered devices worn by animals, which feed data to Project Icarus, weigh around three to four grams, with a one-gram device—the weight of a paperclip—in development. In addition to logging an animal’s GPS coordinates, the tags can also monitor their health by sensing body temperature and their environmental conditions such as humidity, air pressure, and acceleration.

Having a light and unobtrusive monitoring tag is crucial. If tagged animals were negatively impacted by their weight or shape, it could send scientists inaccurate information about the health and movements of a particular species.

“We have done tracking of [tagged] blackbirds and songbirds for the last 10 to 15 years, and we know they reproduce fine,” says Wikelski. “The ones with the tag survive a little better—we don’t know why. Maybe predators don’t like them.”

Next year, Wikelski says he and his collaborators plan to tag and begin continuously monitoring somewhere between 5,000 and 10,000 animals, eventually tagging 100,000 animals.

Wikelski sees potential far beyond learning the routes and timing of animal migrations.

For example, could snow vultures flying near the Himalayas’ 8,000-meter peaks help monitor dangerous weather conditions for Everest’s climbers? Can goats grazing along the flanks of Italy’s Mount Etna volcano detect signs of an imminent eruption? Or might the behavior of different bird populations around the world help epidemiologists track avian influenza?

These are all questions Wikelski sees potential for this ambitious new technology to answer.

“We think the info will be so valuable that government insurance agencies will rely upon it,” Wikelski says.

And when we see how valuable animals are to so many of Earth’s systems, he hopes we’ll be motivated to better protect them, saying, “If people understand how important animals are, then they will have a new appreciation for them.”