Is the Wild West Dead?

In the age of Google Earth and GPS, places that are truly off the grid have real psychological value, author says.

Jason Mark, cofounder of the largest urban farm in San Francisco, is a passionate outdoorsman and hiker.

In his new book, Satellites In The High Country: Searching For The Wild In The Age Of Man, Mark takes us on a journey across America in search of wilderness, from a reservation in South Dakota where the reintroduction of bison has divided the community to a cave in Washington state where a British cavewoman is replicating life in the Paleolithic more than two million years ago. Along the way, he explores the meaning of wilderness and the urgent need to conserve what remains of it.

Speaking from his home in Oakland, California, he explains why the Lakota fought against the reintroduction of bison to their lands, how young people need to discover that yes they can exist without selfies, and why political liberty needs blank spaces on the map free of corporate or government interference.

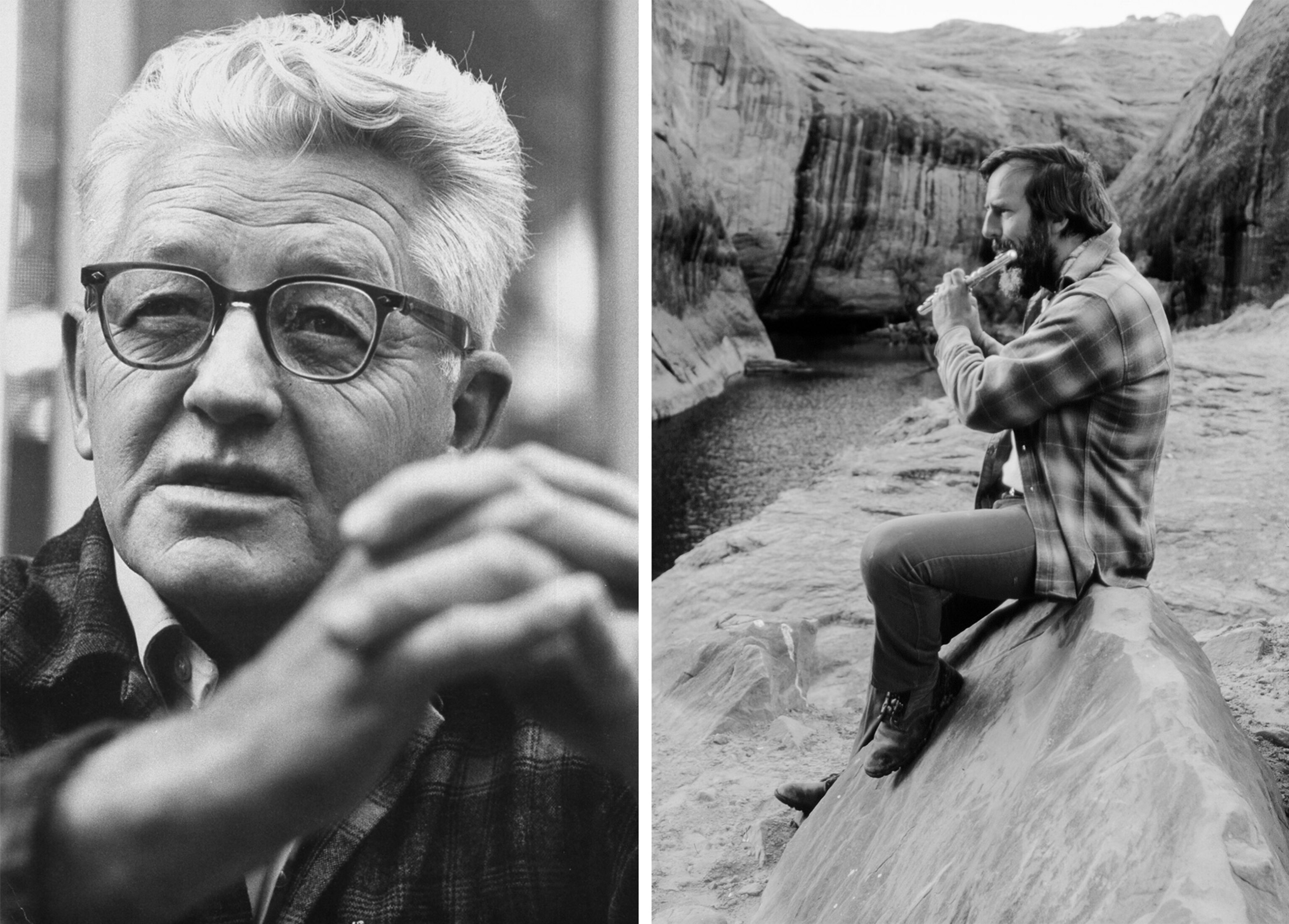

Edward Abbey wrote, “Wilderness is not a luxury but a necessity of the human spirit.” Is that a sentiment you share—and why?

The spirit of Ed Abbey hovers over this book in large measure. I think we need wild places more than ever in what some are calling the Anthropocene or Age of Man. We need wilderness for ecological reasons as a safe harbor for plants and animals at a time when global climate change is increasingly dislocating them from their historical ranges and habitat.

We need wilderness as a psychological tonic.Jason Mark

We also need wilderness as a psychological tonic—the benefit of having places that are off the map. With Google Earth and GPS, to still have places where humans are not dominating the landscape has real psychological value. In the spirit of Abbey, I would also say that wilderness has got civic or political values. Liberty benefits from having places beyond the reach of corporations and the power of the government.

Why did you call the book Satellites in The High Country?

The phrase comes from a scene in the last pages of the book where I am shadowing some young men on an Outward Bound course in the Colorado Rockies. We were at about 8,000 feet, at night, the firmament was crystal clear. I looked up in the sky and saw what looked like a star on the move—a satellite tracking across the sky. It became a good five-word encapsulation for the idea that there’s nowhere left, including the night sky, that’s pristine anymore. The human insignia is everywhere. Yet, as I say in the closing words of the book, Earth remains a beautiful mystery.

Rewilding is a movement happening here and in Europe. Describe the thinking behind it—and whether it can succeed.

I’ll give a plug here for George Monbiot’s book, Feral. Rewilding is the idea that, having extirpated many species, by returning large animals and birds like the California condor to the landscape, we can restore key ecosystem functions.

The most famous example is probably the reintroduction of grey wolves to the northern Rockies and the Mexican grey wolf to the desert Southwest in the mid-late’90s. There’s a phenomenon called trophic cascade, which means that a large predator like a wolf has a regulatory effect on the entire food chain. In Yellowstone, the return of wolves has meant that the elk can’t be fat and lazy and start to browse in a different fashion, which in turn allows aspen and beavers to come back.

If 20th-century conservation was about drawing lines on a map and saying, this is a park or preserve, 21st-century conservation is about filling in those lines, bringing back animals that have been extirpated.

Sometimes attempts to reintroduce species can backfire. Tell us about bison and the Lakota.

As a journalist you always try to go with your eyes wide open and let the story come to you. I went to the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation, home of the Ogallala Sioux or Lakota, because whispers had gotten into the national media of an unprecedented effort by the U.S. National Park Service to return half of Badlands National Park to the Lakota Nation and create the U.S.’s first tribal national park.

It was surprising to me how remote you can still get in the Lower 48.Jason Mark

There are tribal national parks in Canada, Australia, and Africa, but this was to be the first in the U.S. Initially, the Lakota were hugely enthusiastic. But when it became clear they were going to reintroduce bison to Badlands, many Lakota became incensed because they are now cattle ranchers, and cattle and bison don’t mix.

By the time I got to Pine Ridge, there was a raging controversy over whether to bring back bison. All the stereotypes were turned on their heads. Many members of one of the most iconic Indian nations, the same nation as Crazy Horse and Sitting Bull, were arguing against the reintroduction of the bison.

It was ugly. People were at each other’s throats. Some Lakota were saying, “Wow, I can’t believe we would be arguing against bison reintroduction!” Others were saying, “Listen, the only thing that works here economically is cattle ranching. This bison reintroduction is not gonna work.” It goes to show how everyone has a lot of often contradictory ideas about where we can fit wildness into our lives.

The paleo diet has recently become fashionable. You spent time with a modern day cavewoman. Tell us about Lynx Vildern.

[Laughs] She’s an extraordinary character! London born. Stepfather was the head of the St. Martin’s School of the Arts. She was a London and then Amsterdam punk in the heyday of the punk movement in the ’80s. In her words, she was, “killing herself faster than she wanted to” with drugs and alcohol.

So she went to the woods of Sweden where her grandmother lived and had an epiphany that she wanted to live in the wild. For the last two decades she’s been living in some of the wildest places in North America, first in New Mexico and now in Washington. She has also become one of the world’s foremost instructors in primitive skills, teaching people how to make fire with two sticks, hunt with a homemade bow, and dress an animal.

What makes Lynx especially interesting is the ambition of her endeavors. For the last ten years, she’s organized something called the Stone Age Living Project, where she and other neo-primitivists go into the wilderness and see how long they can survive using only Paleolithic technologies. She calls herself a time traveler.

She’s under no illusion that this is anything more than an experiment, and yet she feels that the experiment has a lot of value in exploring our relationship with nature. It’s a kind of human rewilding, where we try to shed some of our post-modern consciousness, which isn’t easy. A young woman from Devon, England, who had made her way to Lynx’s place, said, “I’m walking through the wilderness wearing deer skins and carrying all my food in a tump strap, yet Britney Spears is still pumping in my head!”

What surprised you most in your adventures into the wild? Do you have a favorite wild place?

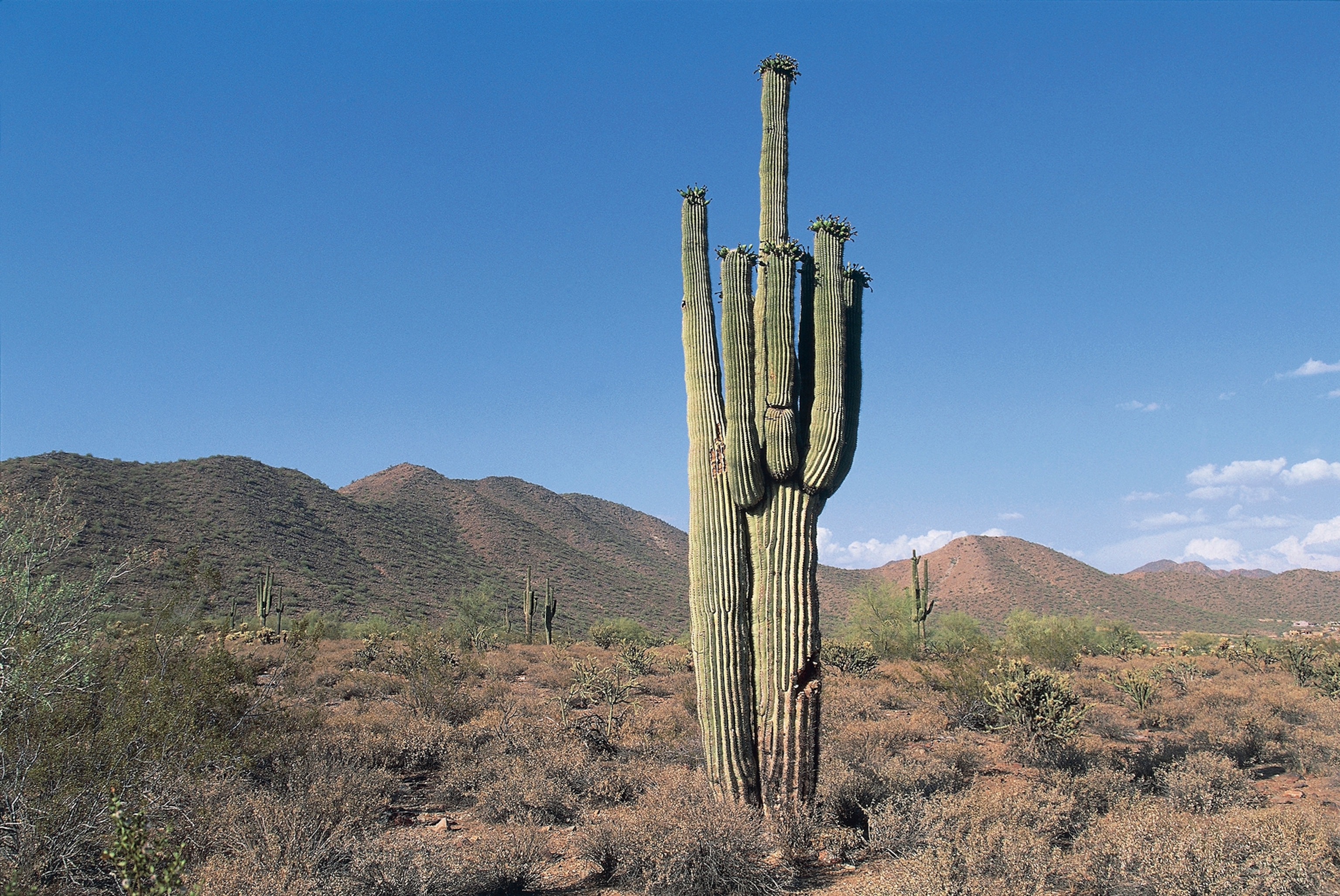

It was surprising to me how remote you can still get in the Lower 48. I grew up in Phoenix, Arizona, and I know the Southwest. But what was surprising was how deeply wild the Greater Gila of Arizona and New Mexico is. You expect it in Alaska, but people in that section of Arizona and New Mexico never set out without a couple extra gallons of fuel and water in their vehicle because if you break down, you’ve probably got a 40-mile walk. So, even in the Anthropocene, there’s still a lot of wildness out there.

The National Park Service will have its centennial in 2016. What would you like to see change in the agency’s management?

I’d like to see the national parks expanded. We need more of them, not less. We’ve seen very few parks authorized in the last eight years.

The National Park Service does a great job of balancing the interests of what we’d call the front-country users—people mostly interested in car camping or staying at lodges, with the backcountry enthusiasts, who want to go places they can only get to on their own two feet. It’s important to have all those different entry points for people, so that folks can engage in nature at whatever level feels comfortable for them. Not everybody’s going to want to climb Half Dome! [Laughs]

I went to see A Walk In The Woods the other night, and there was almost no one under 60 in the audience. What are the challenges in inspiring a love of wild places among young people?

It’s a serious issue. The ranks of backcountry and wilderness enthusiasts are greying, and we run the risk of losing a political constituency that understands why wilderness is important. One of the biggest challenges is simply access or introduction.

In some ways it’s an esoteric art. Whether you’re hunting, angling, or backpacking, you need someone to introduce you to it because it can sometimes be dangerous, and you need to know what you’re doing. There are a lot of great programs doing that. I recently got an email from a program here in Northern California called Bay Area Wilderness Training. The headline was, “I exist even without a selfie.” It was a quote from a kid at Middle School, whose head had been turned around by being off electronic devices for 72 hours. Nobody’s saying we’re going to shed all these wondrous devices. I’m talking to you from an iPhone! The challenge is to connecting with young people, who are so awash in digital entertainment.

I went backpacking on Labor Day weekend in the Sierra Nevada, and I can see why some folks wouldn’t be into it because frankly it’s kind of boring [Laughs] That’s the thing about wild nature! When you go into the wilderness, not much happens on the human scale. If you see a bear or elk, it’s a thrilling experience, but most of the action passes unseen. Things are moving at a much slower pace than we are accustomed to.

Most Americans have spent their entire lives in the anthill of civilization.Jason Mark

To most Americans, the wilderness is nothing more than myth. They may have seen some amazing YouTube video or a National Geographic show, but they haven’t actually been there. They’ve spent their entire lives in the anthill of civilization. The challenge for the Park Service and institutions like NatGeo is to give people a taste for wilderness so they want to go and explore for themselves.

What do you hope readers will take away from your book?

Two things. I was overhearing a conversation, especially within academia, that wilderness was dead and that we live in a post-wild world. While I get that at an intellectual level, it made me uncomfortable at an emotional level. That’s why I did the book. Is there anything that’s still truly wild?

I’m hoping this book provides new intellectual ammunition for the defenders of the wild and allows them to respond eloquently to the folks saying that wildness is dead.

I’m also hoping to inspire people to recognize that there’s a lot of wildness out there, understand why that’s important, and then commit themselves to defending and preserving it. If this book in some modest way fosters the movement to conserve and restore wild places, I’d be very happy.

Simon Worrall curates Book Talk. Follow him on Twitter or at simonworrallauthor.com.