This could be the oldest evidence of fire-making

A new study pushes back the advent of fire-making by more than quarter of a million years.

Archaeologists have discovered what may be the earliest evidence of deliberate fire-making.

At a site called East Farm in England, recent excavations revealed reddened silt, flint handaxes distorted by heat, and fragments of a mineral—iron pyrite—that could have been used to make sparks on tinder. Taken together, the finds suggest that an early group of Neanderthals deliberately and repeatedly set fires in a hearth there roughly 400,000 years ago.

"In over 36 years of field work and geological studies in the area, we've never found pyrite before," says British Museum archaeologist Nick Ashton, the senior author of a study of the discoveries published in the journal Nature on December 10. "And now, the only time we find it is alongside heat-shattered handaxes and baked sediments."

While the several distinct pieces of evidence make a strong case, figuring out if early humans lit flames on purpose is hard because the archaeological traces of natural and human-made fires look very similar. But if the finds hold up, they would shift the first fire-making back by more than 350,000 years and add to evidence that Neanderthals mastered flames independently of early modern humans.

Evidence from fool's gold

The East Farm site, about 70 miles northeast of London near the village of Barnham, was discovered more than 100 years ago. Early excavations revealed stone tools from more than 400,000 years ago, during the Lower Paleolithic period or Old Stone Age. Scientists think hunter-gatherer groups of early human ancestors lived in the region, possibly Homo heidelbergensis; and that all of Britain at that time was connected to the European continent by a land bridge known as Doggerland. Ashton says the East Farm site may be the remains of a seasonal camp.

Some nearby prehistoric sites also show evidence that early hominins were using fire, but researchers are unable to tell if the fires were lit deliberately or if they were sourced from natural wildfires. (The evidence for the humans capturing fire from wildfires for their own uses goes back over a million years to the early hominin Homo erectus.) But the East Farm excavations are the first in the area to find fragments of iron pyrite that seem to have been from a fire-making kit, Ashton says. In addition, a few fragments of ancient skulls unearthed at other sites suggest that early Neanderthals may have lived there at that time, though the team can’t rule out the possibility that the pyrite belonged to Homo heidelbergensis.

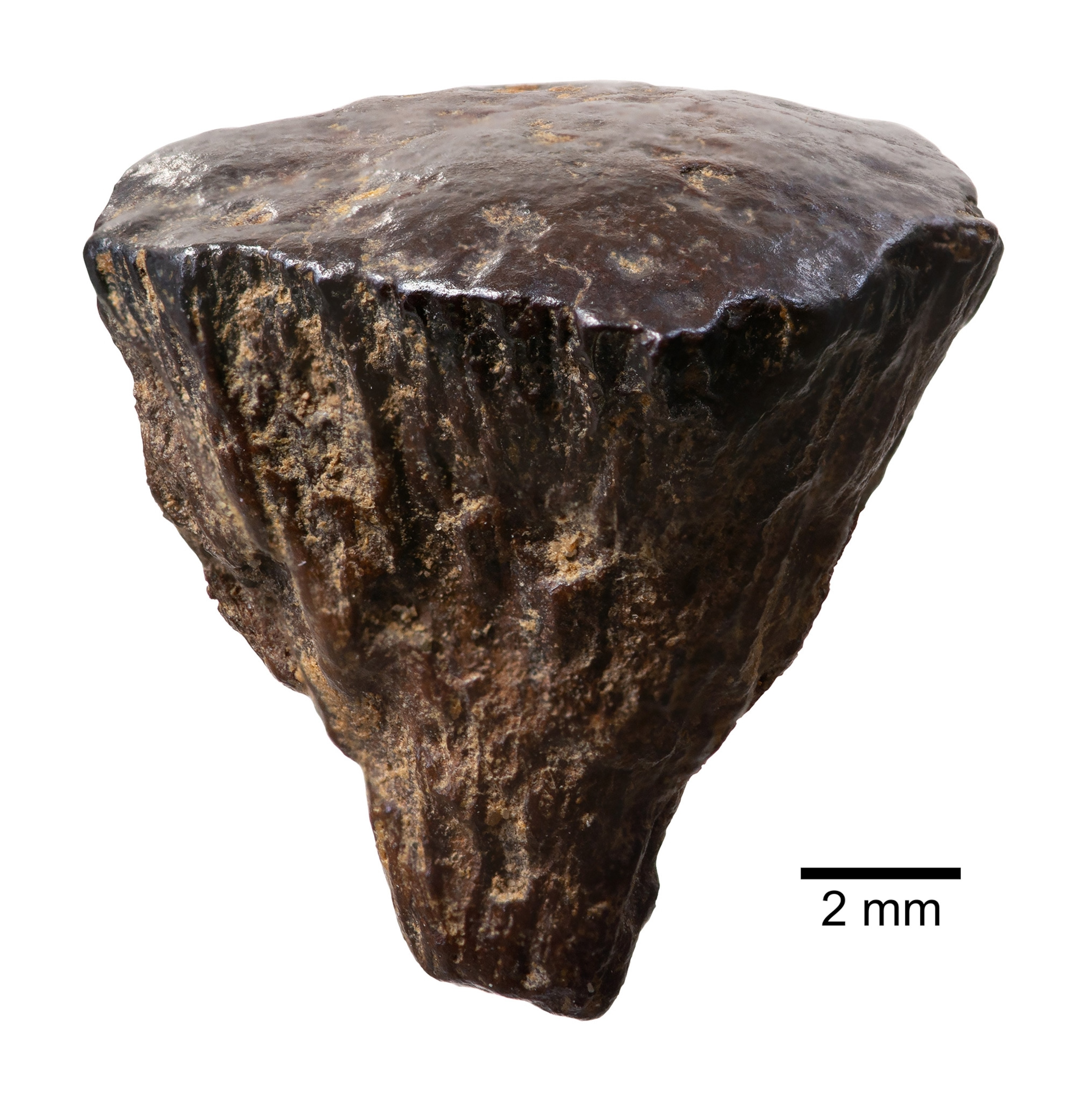

Iron pyrite—sometimes called "fool's gold" because of its golden sheen—is a mineral form of the chemical iron disulfide. When struck sharply with flint, the substances combine to create bright sparks that can start fires in specialized tinder; wood scrapings or dried mushrooms were often used, Ashton says.

The mineral can also form naturally from chemicals in the ground, notes study co-author Andrew Sorensen, an expert on prehistoric fire at Leiden University. But that typically happens hundreds of yards below the surface at East Farm, while these fragments were found just a few feet down. "No pyrite-bearing outcrops or geological deposits are known in this region, [which] suggests they were brought in by hominins," he says.

Ashton says that observed changes in the geomagnetism of sediments around the hearth suggest fire was repeatedly made there; infrared spectroscopy shows clear signs that the sediments were heated, sometimes to more than 1300 degrees Fahrenheit; and there are traces of chemicals called polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons that are typically formed by burning wood. "All these things contribute to our understanding that this was not a natural fire," he says.

The evidence for fire control at East Farm was consistent, says archaeologist Ségolène Vandevelde from the Université du Québec à Chicoutimi who was not involved in the study but wrote an analysis of it for Nature. "The strength of this research is really the effective combination of different types of expertise and complementary methods," she says. And she notes the evidence suggests this fire-making technique was already well-known: "If the ability to light fires is so ancient, we can assume that the mastery of fire and its habitual use dates back even further," she says.

The prehistory of fire

Researchers have long thought that our ancestors harnessed wildfires and carefully used those flames for campfires before Homo sapiens later mastered lighting fires themselves. But the true control of fire was a "turning point" in human history that affected almost every facet of life and enabled the later transformations of agriculture and metallurgy, British Museum archaeologist Rob Davis, the study's lead author, told an online news conference.

He notes that the ability to make fire "would have had an impact on evolutionary trends, in particular on biological evolution, but also on social evolution and social developments." Fire was important for many obvious things, like protection from predators, providing light and heat, and for cooking food. But fire also features in many human belief systems, and it would have enabled early humans to live in colder places.

The previous evidence of fire-making was also found at Neanderthal sites, including one in France from about 50,000 years ago that held the oldest record. But Homo sapiens were living in Europe by that time, and so scientists reasoned that the Neanderthals might have learned to make fire from them. The ancient evidence from East Farm, however, indicates that Neanderthals purposefully lit fires before our species emerged in Africa around 300,000 years ago.

"This is something that we shared with our evolutionary cousins," Davis says.

(Inside the last days of the Neanderthals.)

Cautious criticism

Before Neanderthals can share credit for this innovation, more evidence is needed.

Leiden University archaeologist Wil Roebroeks, an expert on the prehistoric use of fire who was not involved in the study, sees the new find as " a new addition to the early fire record" but isn’t satisfied that the fire-making at East Farm was deliberate. "The authors did an excellent job with their analysis of the Barnham data, but they seem to be stretching the evidence," he says.

Others hope that researchers can build on the East Farm analysis. "I would certainly like to investigate it more, to see if this could be confirmed somehow," says Dennis Sandgathe, an archaeologist at Simon Fraser University who studies Neanderthal fire use but was not involved in the latest work. Though he says he is skeptical of many ancient fire-making claims, he found the new paper “quite compelling.”

Even if the East Farm evidence is confirmed, however, Sandgathe cautions against supposing that fire-making was widespread at this time: "The current evidence still suggests that this would have been an exceedingly rare thing."