Shipwreck May Hold Clues to Famous Lost Expedition From 1800s

Recent underwater search yields new artifacts and glimpse inside ship that mysteriously disappeared 167 years ago.

Unusually calm weather and clear water during the waning Arctic summer has helped Canadian archaeologists get their best look yet inside their nation’s most famous shipwreck, the Franklin Expedition’s H.M.S. Erebus.

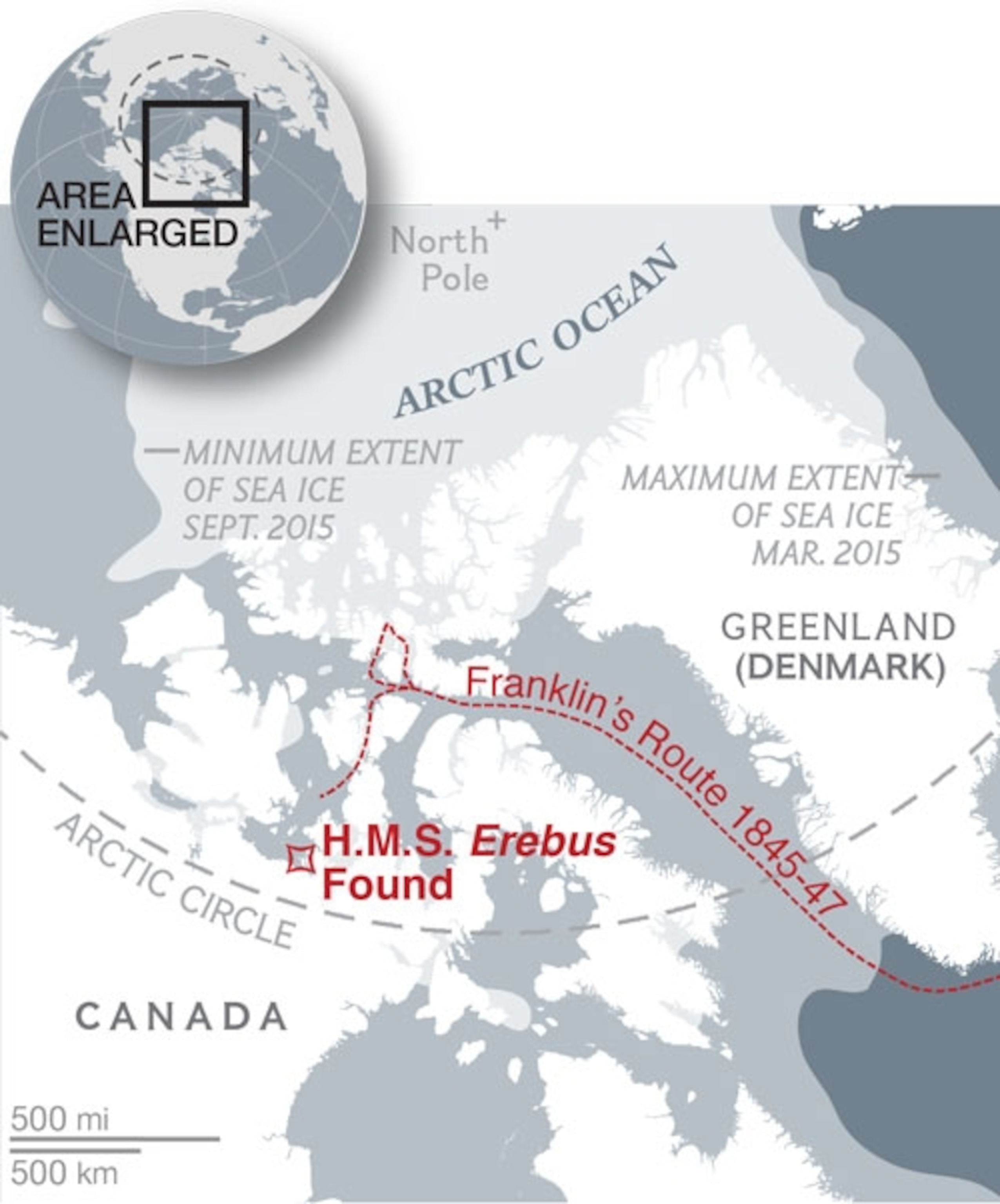

Dispatched by the British admiralty in 1845 to search polar waters for the fabled Northwest Passage from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific, the expedition led by Sir John Franklin was soon lost. For more than a century and a half searchers combed Canada’s high Arctic in vain for the expedition’s two ships, H.M.S. Erebus and Terror.

Last year, Canadian Prime Minister Stephen Harper announced that a Canadian scientific team had located Erebus in less than 40 feet (12 meters) of water in a remote Arctic strait. (Read more about the discovery of H.M.S. Erebus.)

This past summer the Canadian team returned to the Arctic to study the ship’s well preserved remains and peer inside. Inserting cameras through holes in the vessel’s upper deck and hull, the team spied the shattered remains of expedition leader Sir John Franklin’s cabin. Part of the stern where Franklin’s quarters were located has collapsed, trapping what appear to be his furnishings and possessions under beams and planking.

(Read about the discovery of H.M.S. Erebus.)

“Probably a good percentage of the contents of Franklin’s cabin is either entombed within the crushed cabin itself, or deposited on the seafloor,” said Jonathan Moore, a senior underwater archaeologist with Parks Canada.

In contrast to the heavily damaged stern, much of the ship is remarkably intact, raising hopes that archaeologists may be able to probe the hold at some point in the future. There they might find scientific specimens collected during the expedition and possibly even photographs.

(Read about 5 shipwrecks archaeologists want to get their hands on.)

“A lot of the things that could tell us about the fate of the Franklin expedition are trapped deep inside the bowels of the ship,” said Ryan Harris, the Parks Canada underwater archaeologist who led the recent research effort. “Before we go inside, we want to know how it’s holding together, and what reinforcement we need to do.”

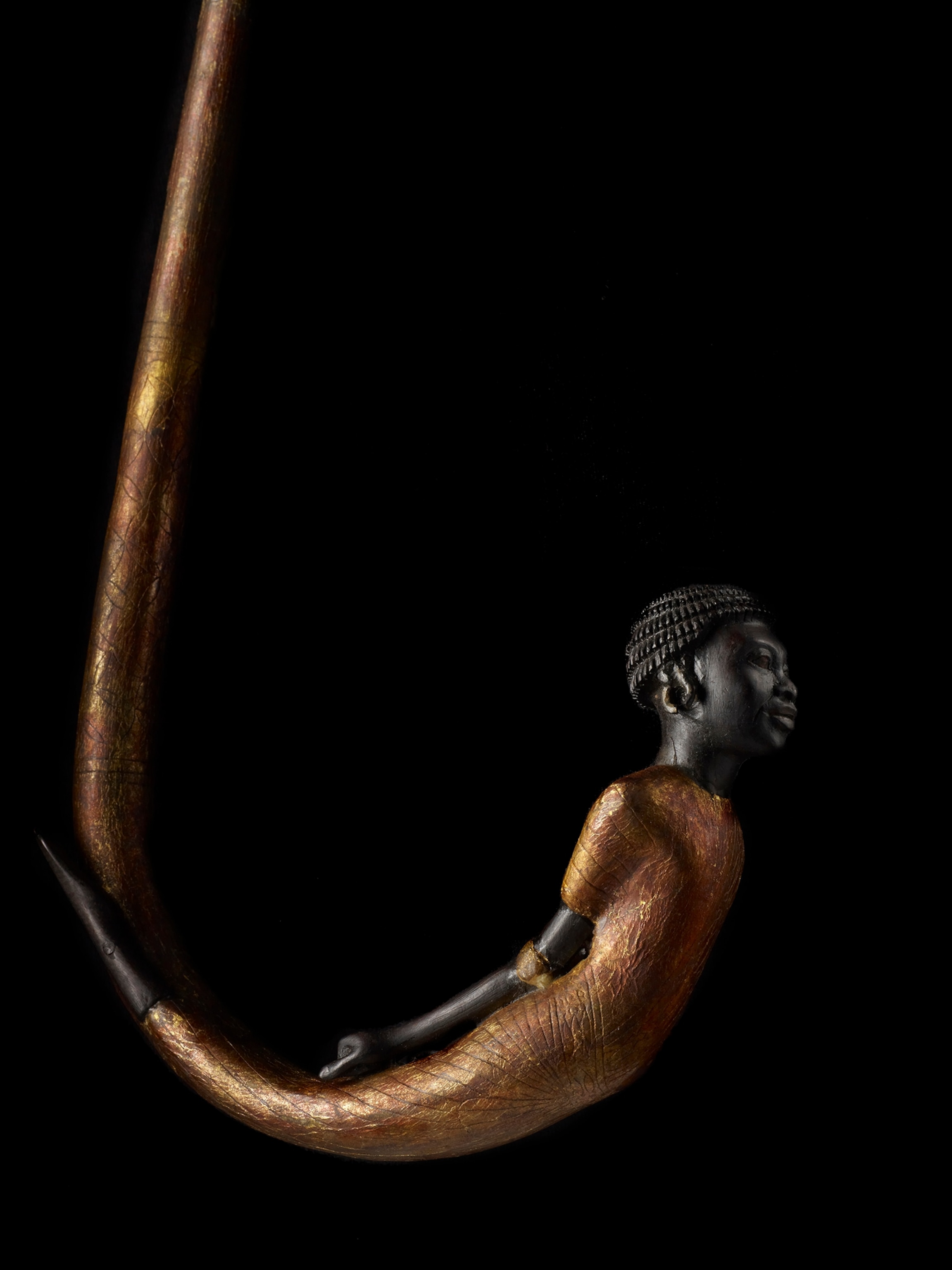

During more than 140 hours of dives in August and September, Harris and his team took hundreds of photographs to map the wreck site. They also recovered dozens of artifacts from the debris field, including the ship’s wheel and the hilt of a Royal Navy officer’s sword. “I think we’ll probably find much, much more in the debris field in years to come,” Harris said.

Allure of an Epic Failure

Led by a veteran Arctic explorer and outfitted with state-of-the-art technology—from central heating to newly invented daguerreotype equipment for photography—the Franklin Expedition seemed destined for success. But 16 months after their departure, both ships had become trapped in sea ice. In June 1847, Franklin died, possibly from a heart attack. The remaining crewmembers abandoned the ships less than a year later, hoping to trek across the sea ice to a Hudson Bay Company outpost on the Canadian mainland. None survived the journey.

In the following decades, search and rescue parties combed Arctic waters for traces of the lost expedition, turning up a last written message in a cairn, as well as graves of some of the men. As hopes of rescuing crew members dimmed, the story of this lost Arctic expedition became enshrined in Canadian culture, becoming the subject of popular novels, paintings, and songs.

The lost expedition’s allure “is like the appeal of the Titanic and Antarctic explorer Robert Scott,” says nautical archaeologist James Delgado, director of NOAA’s Maritime Heritage Program. “It’s an epic failure on a grand scale, where people met their fate with resolute determination.”

Search for Terror Continues

As this summer’s work proceeded on Erebus, Harris and a small crew also searched for Franklin’s other ship, H.M.S. Terror. Their target area was more than 80 miles (130 kilometers) away from Erebus, a location suggested by historical evidence and other data. Searchers scoured hundreds of square miles of seafloor with sonar technology but came up empty handed. “We haven’t found the Terror, or any sign of it,” Harris reported.

Even so, the researchers remain optimistic about the fieldwork yet to come. In 2016, the team plans to resume searching for the Terror and begin excavating around Erebus to recover more of the artifacts scattered there. “We don’t know what all we might find,” Harris said. “It’s very, very exciting.”

Follow Heather Pringle on Twitter and on Facebook.