South China Sea Tensions Illustrate Pacific’s Tumultuous History

It’s “melting point and meeting point” between East and West, says Simon Winchester—also the birthplace of surfing and test site for the Atomic bomb.

In 1520, after surviving the raging seas of what later became known as the Strait of Magellan, the Portuguese explorer Ferdinand Magellan entered the calm waters of a vast, new ocean and named it “pacific.”

But in recent years, the Pacific Ocean has become distinctly unpacific as a resurgent China flexes its naval muscles in the South China Sea. In Pacific: Silicon Chips and Surfboards, Coral Reefs and Atom Bombs, Brutal Dictators, Fading Empires, and the Coming Collision of the World's Superpowers, best-selling author Simon Winchester plumbs the depths of the ocean that is the birthplace of surfing, the crossroads of East and West, and encompasses a dazzling array of races, cultures, religions and climates.

(The Cham: Descendants of Ancient Rulers of South China Sea Watch Maritime Dispute From Sidelines)

Speaking from New York, he explains why one of his heroes is a British meteorologist named “Boomerang Walker”; how China is converting coral reefs into military bases; and why the epic voyage of the traditional Hawaiian vessel, Hokule’a, offers an alternative vision of the Pacific as a place of peace.

You write, “The Pacific is an oceanic behemoth of eye-watering complexity.” Make our eyes water, Simon.

It’s very big—64 million square miles. You could put all the other oceans and continents in it. It’s got an extraordinary number of countries around it including Alaska on one side and Russia on the other, going all the way down to Australia and New Zealand and Chile.

There are hundreds of islands and island groups: Micronesia, Melanesia, Polynesia. It’s where, quite literally, East meets West, where the western-moving peoples of the Americas finally bumped up against the peoples of the East: the Chinese, the Indonesians and Filipinos. It’s a melting point and a meeting place; the completion of the full circle of human migration; a bewildering assortment of racial types and religions.

The poet, Robinson Jeffers, described it as “ the unsleeping eye of the earth,” because if you look at the world from outer space you’ll see this big, blue thing. That unsleeping eye is the Pacific.

You begin the book not with tropical palms, but a mushroom cloud. Tell what happened to the island that gave its name to an itsy-bitsy-teeny-weeny piece of beach attire.

Not a lot of good, I’m afraid. In the early 1950s, once the Americans decided to push ahead with their program of thermonuclear weapons, they needed somewhere to test them. The Pacific seemed just the ticket, because the Americans had colonial sovereignty over vast acreages of apparently or more or less nearly empty ocean.

They needed to find an island with very few people within striking distance of an airfield where they could drop these new and terrible weapons. They decided on the island of Bikini, about 250 miles north of an airfield on the island of Kwajalein. To get the people to leave they used the most cunning sleight of hand, invoking to the Christian islanders the book of Exodus, in which the Lord led his people out of Israel behind a pillar of fire. The Americans said to these people, who numbered about 170, we too can create a pillar of fire for you; a signal that you should leave your island.

It sounds utterly bizarre, but the islanders agreed and left. The Americans then exploded 25 enormous weapons, including the biggest of all American weapons, the Castle Bravo test in March 1954, which utterly devastated and polluted the islands. They’ve been uninhabitable ever since, and many people have been affected by radiation. Today the word bikini is the name for an attractive bathing costume, but in the Pacific it is a watchword for death, disaster and radioactive mayhem.

You write, “Much of the dirty business of the modern world would be conducted in the Pacific.” Explain.

It was not just the Americans. The British dropped nuclear bombs on Christmas Island. The French did the same in Polynesia. So there’s a lot of radioactivity. There’s also undersea mining, which is tearing up the subsurface of the sea; and extinctions of wildlife. Ever since Westerners invaded it, after Magellan, it has been treated unkindly. So part of the book is a lament for the beautiful, vast, pristine ocean it once was, but which sadly no longer exists.

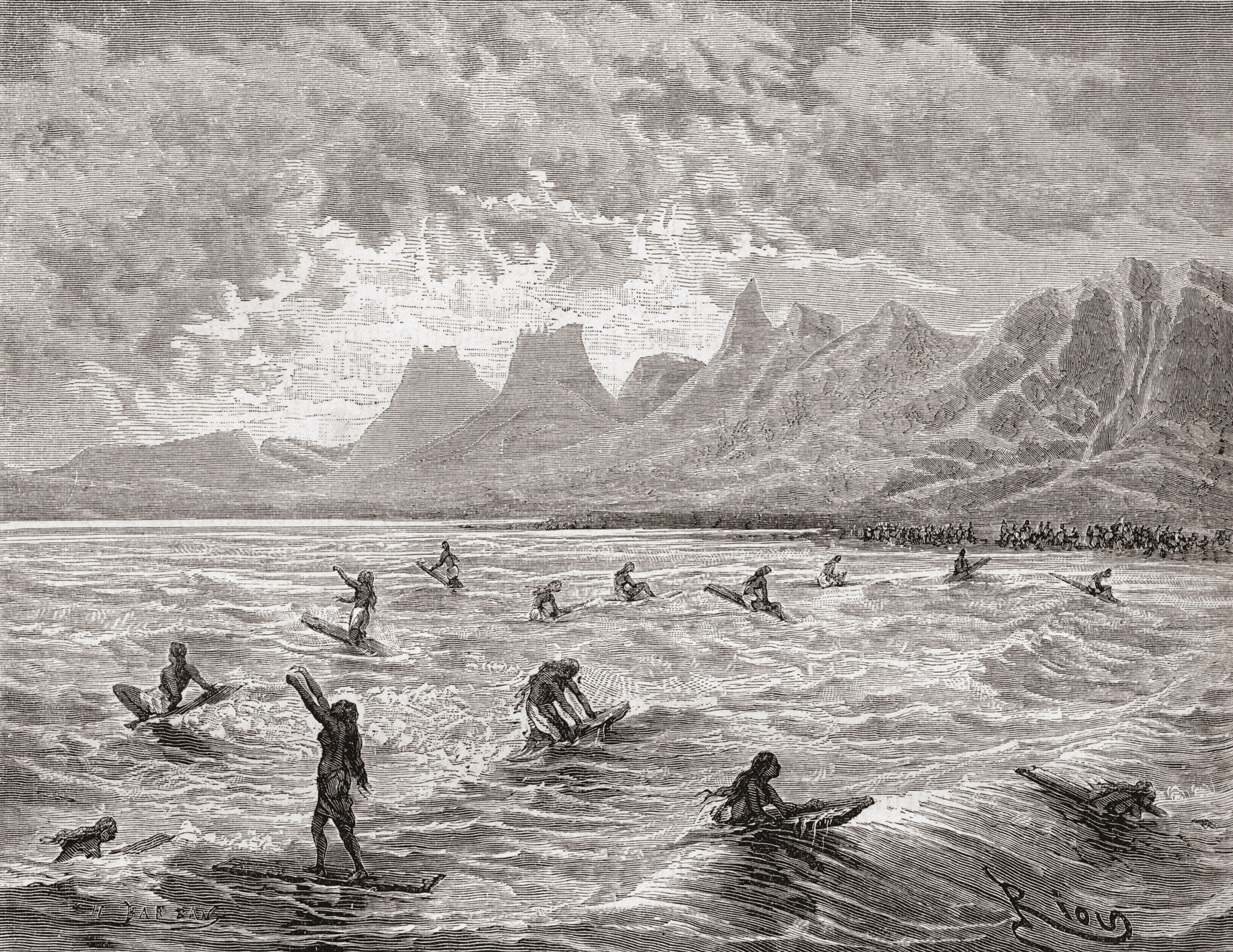

Let’s lighten up a bit and talk about “wave-riding.” How does surfing reflect the identity of the Pacific?

One might argue that surfing is the Pacific’s great gift to playtime. There are pictographs of people riding waves on boards dating back hundreds, or thousands of years in Tahiti. But it really took hold 2,500 miles further north, in Hawaii. There was a complex system of which beaches the Hawaiian aristocracy could use and which the Hawaiian commoners could use and rules about the length of boards. This all went on largely unknown to Westerners until 1907, when Jack London, who had already established quite a reputation for himself as a writer, was going round the world on a little boat called The Snark.

He stopped with his wife in Hawaii. One day he was swimming off Waikiki when hundreds of little boys on boards shot past him. He thought, my God, what’s going on? That looks absolutely terrific fun! So he got two local people to teach him. He found it such an ecstatic and enjoyable experience that he wrote a lengthy article for the Women’s Home Companion, which was syndicated around the world. So, all of a sudden, people in New York and California, London and Australia came to know about this new sport of surfing.

But it really took off half a century later in 1959, when a film nobody thought would do much business was suddenly reviewed favorably in the New York Times. The film was called Gidget and starred Sandra Dee as Gidget. She was a shrimp of a girl but managed to master wave riding with great aplomb and grace. Everyone thought, my God, if she can ride these mighty waves, we can do it, too. Since then, surfing has turned into a massive $13 billion industry.

You wrote a famous book about the man who created the Oxford English Dictionary. One of your heroes is another great Briton. Tell us about Sir Gilbert Walker and why you admire him.

He’s one of these wonderful British eccentrics. There are all sorts of circulatory weather patterns in the Pacific and one is the Walker Circulation, so named after the chief meteorologist in British India, a tweedy, somewhat unassuming, pipe-smoking Englishman, who lived up in the observatory in Shimla, in the hills of northern India. From the 1920s to 1940s he crunched numbers, but without a computer. He was fascinated by the monsoon, which is critical to the survival of India.

What makes Walker the kind of figure I love to write about is that he wasn’t an expert. He was also interested in the physics of boomerang throwing, hence his nickname “ Boomerang Walker.” And he wrote eminently on the physics of bird flight. He was one of those great, British polymaths of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, of whom there are too few these days. We’re all specialists. A man who can deal with boomerangs and the monsoon is my kind of guy [Laughs]

You previously wrote a book about the Atlantic. What similarities or contrasts are there between the two stories?

If you accept that the Mediterranean was the inland sea of the classical world, which I think most people would, then it’s reasonable to say that the Atlantic, given all the migration across it from Europe to the Americas in the 19th century, can be thought of as the inland sea of today’s world. The Pacific is where tomorrow’s world is being constructed, particularly the relationship between the West, America, and the East, China. This is where East and West meet and the key question is whether they can conduct themselves in a peaceful manner or whether the Pacific is going to become an enormous battleground.

China is very aggressively asserting its control over the South China Sea. There have been clashes with Vietnam and the Philippines and close encounters with U.S. warplanes. How close are we to a regional war?

The South China Sea is a very important trade route. An enormous amount of oil passes through it on the way from the oil fields in Arabia to Japan and other Asian countries. There is no suggestion that trade will ever be interdicted. However, in recent years, the Chinese have been annexing dozens of little islands and coral reefs dotted across the South China Sea, like the Paracels in the north or the Spratlys in the south. And in the last few years, they have been bringing in dredges and construction teams. There are docks and landing strips with bombers and warships.

How close are we to conflict? I don’t think we’re near conflict at all. But there’s going to be some tough talking going on. The way the Americans are dealing with this is to say, “we’re not going to regard the South China Sea as Chinese territorial waters but as international waters.”

So they are sending their aircraft over the islands and their warships through the passages between the islands. On three occasions in the last two years there have been near-confrontations between Chinese and American vessels. They’ve all been resolved peaceably, but the theory is that—accidentally— there will be an actual confrontation. So the diplomats are working overtime to make sure if there is such an event, it will be resolved peaceably.

You end the book with a different vision of a possible future in the Pacific. Tell us about the voyage of the Hokule’a and its message.

Hokule’a is a 62-foot long, twin-sailed, twin-hulled canoe, which was built in Hawaii as its gift to the Bicentennial in 1976. The belief was that Hawaiians could relearn the old Polynesian techniques of navigating without any instruments, without a compass and sextant and, of course, without GPS. So they set off in this sailing canoe without any technological aids and 2,500 miles later, got to where they wanted to go to, in Tahiti, using just the flight of seabirds, the passage of the stars and the currents.

They have since taken the canoe up to Japan and over to America. Now, they’re taking it round the world. As we speak, it’s in the Indian Ocean, making its way towards the Mediterranean. It will then go to the Atlantic, sail up the Chesapeake and visit President Obama, who grew up in Hawaii.

Polynesian traditional techniques are worth paying attention to. We’ve assumed for far too long that our technology is superior and have disdained what the Pacific islanders have done. But they have shown that they can do things just as skillfully with no pollution or technology, using just an understanding of the wind, the waves and the water. We can learn from them.

The voyage of Hokule’a’ is based on the philosophy of malama honua, meaning respect for our planet. I hope the Pacific will be a place not of conflict but of peace and harmony as it was for thousands of years before we came and started to mess things up.

Simon Worrall curates Book Talk. Follow him on Twitter.