Finding light in Hiroshima's legacy

After discovering that his ancestors had been among those killed in the bombing of Hiroshima, photographer Will Matsuda embarked on a photo project offering tribute to them.

Three years ago, Oregon-based photographer Will Matsuda learned something that totally reframed his connection to the Japanese city where he had ancestral roots––Hiroshima.

His family had received a translated koseki, an official register that records vital information about all Japanese households—marriages, births, and deaths. “It listed a bunch of our relatives’ dates of death on August 6, 1945, and a few days after that,” he says.

That was the day the United States dropped a nuclear bomb on Hiroshima, an act of destruction that razed much of the city, instantly killed tens of thousands of people, and sickened thousands more with radiation poisoning. By the end of 1945, an estimated 140,000 people had been killed.

(The elusive horror of Hiroshima.)

Matsuda’s relatives, including his great-great-grandmother Tama Miyahara, numbered among the dead. “Had the bomb not happened, I would have family to see when I go there,” he says.

As Matsuda reflected on how a violent turning point in human history was a personal tragedy for his family, one thing struck the 32-year-old photographer: how the bomb’s intense heat and light etched shadows of people and objects who had been standing in its path on Hiroshima’s buildings and streets.

“It turned the city into a negative,” he says.

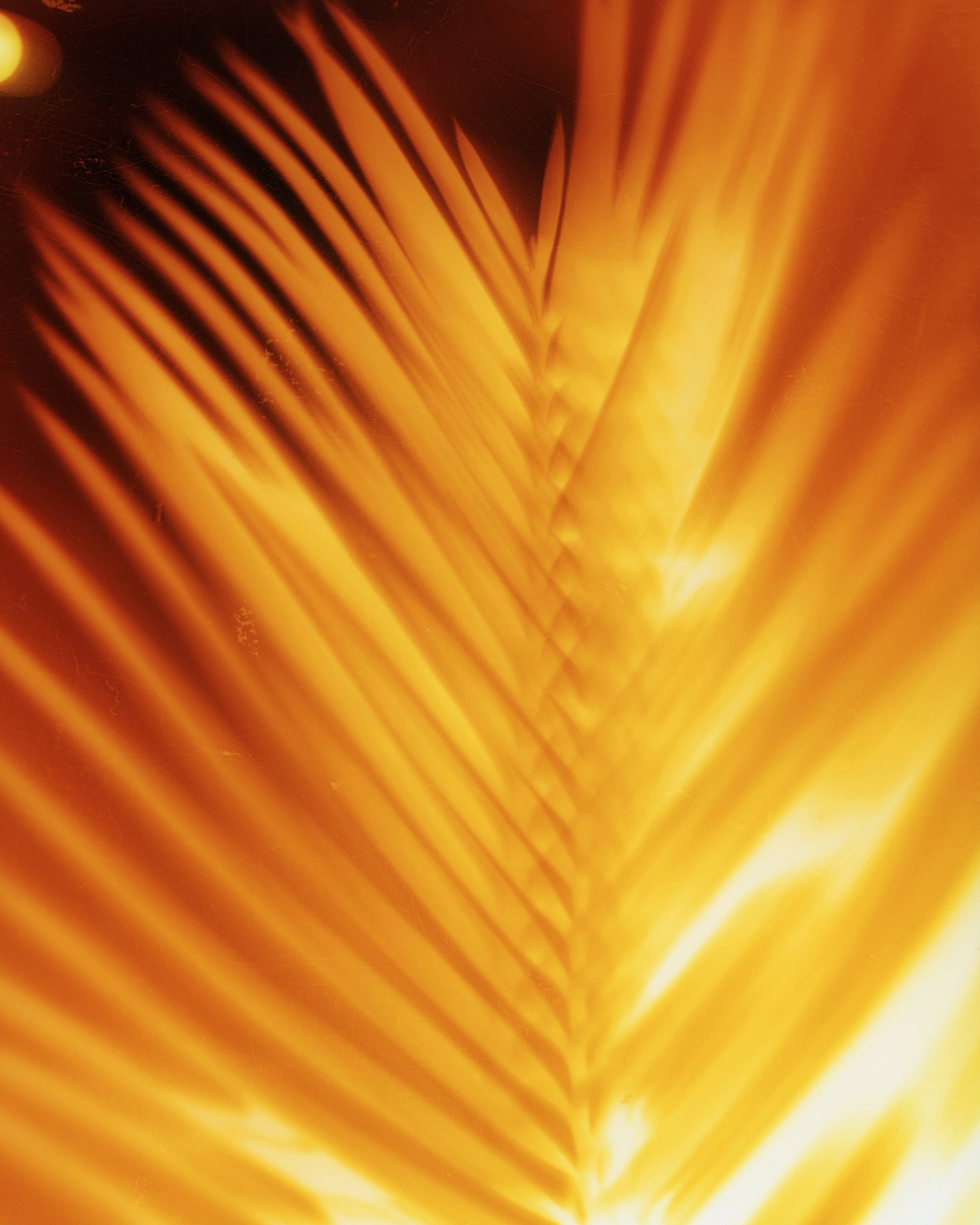

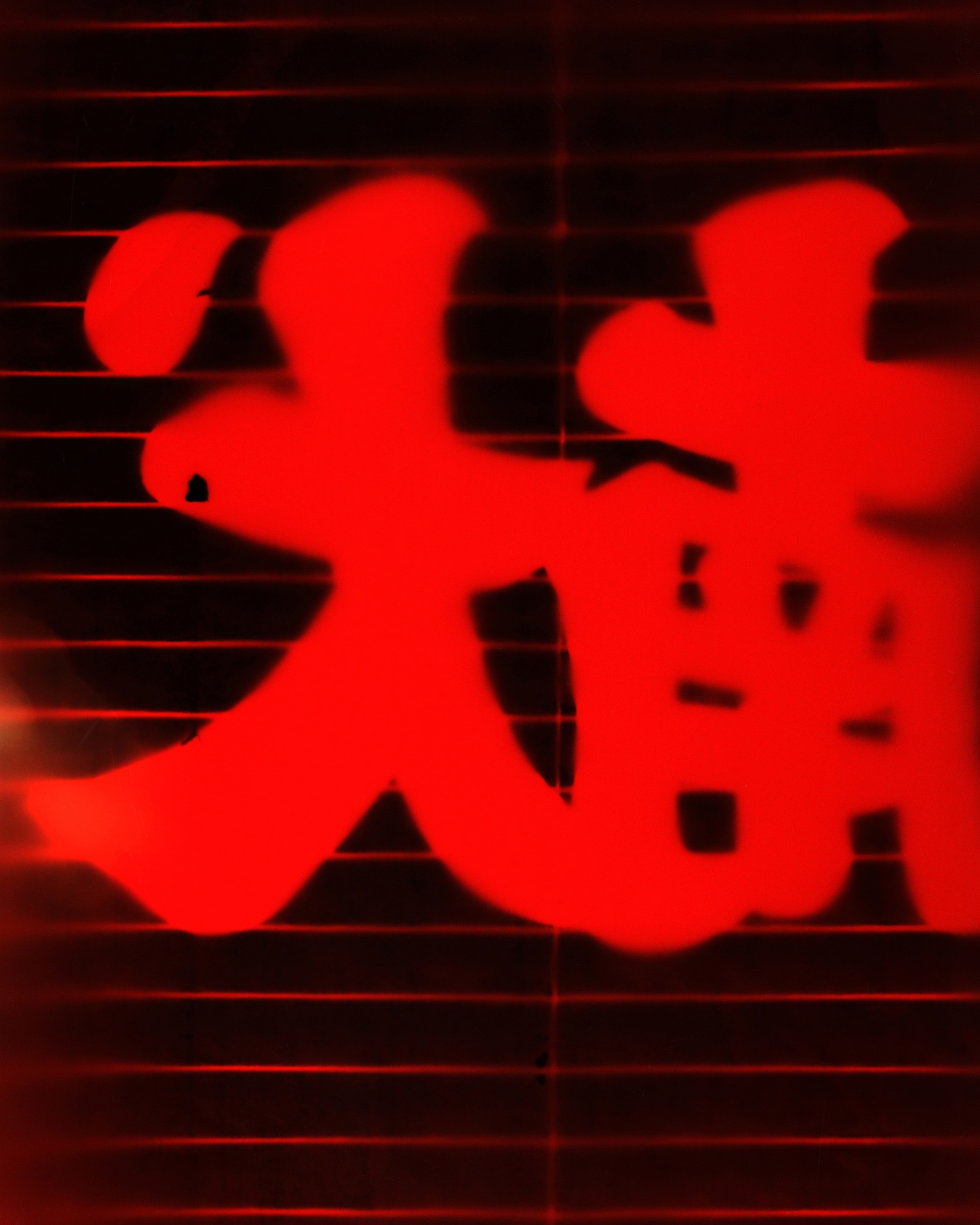

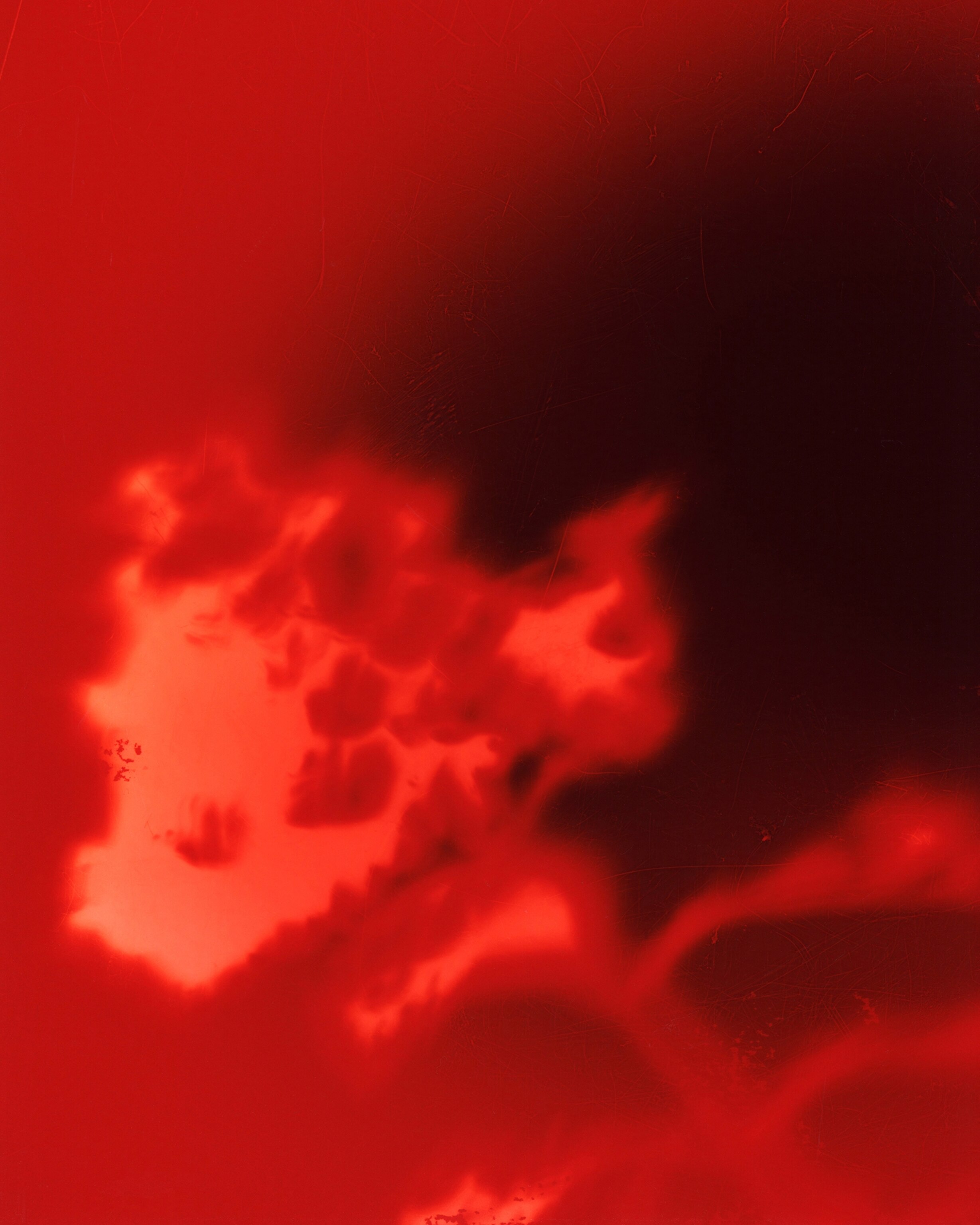

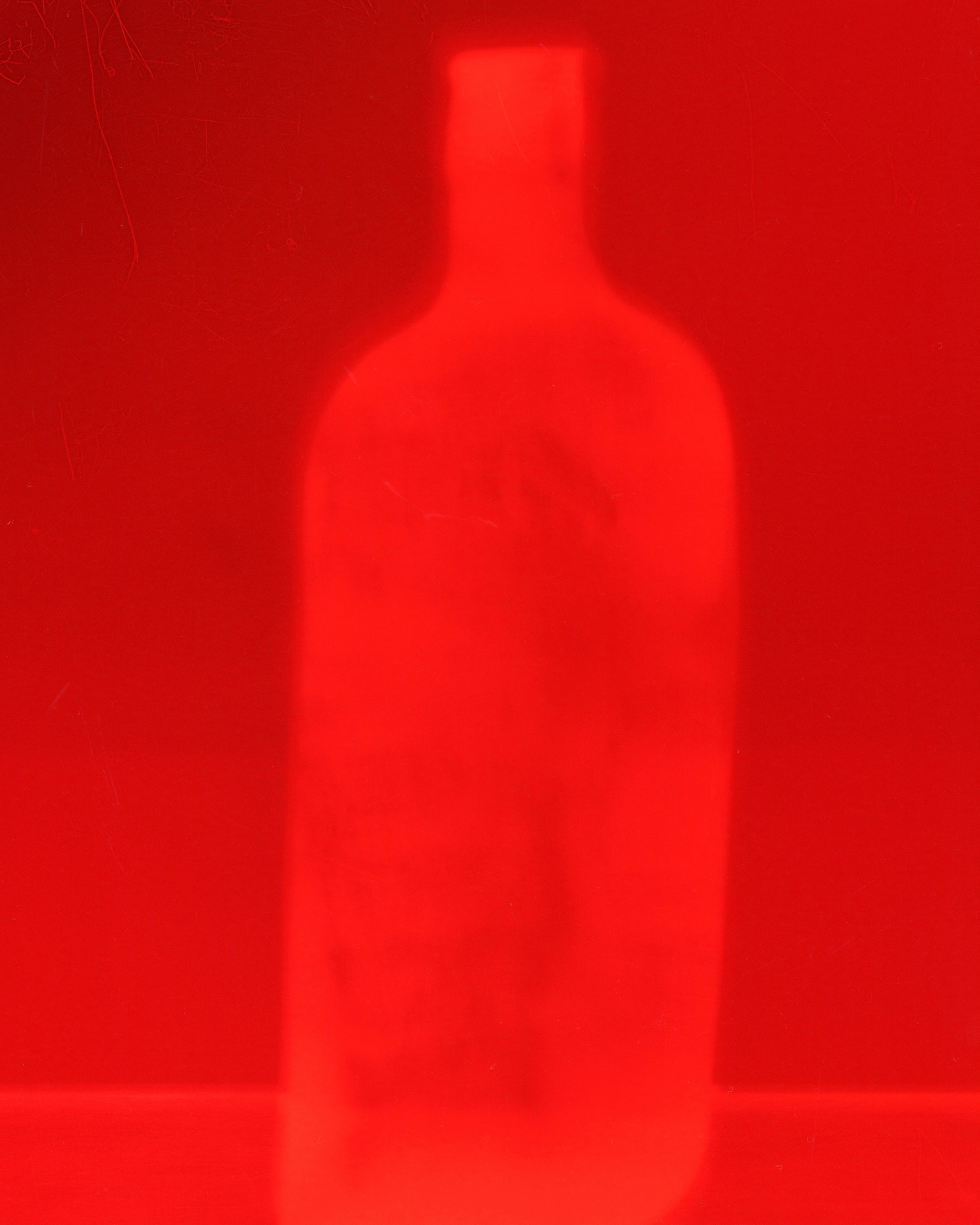

This inspired Matsuda’s newest project: photographing objects in Hiroshima without a camera—instead using a similar process to that which created the nuclear shadows.

To make these images, Matsuda held pieces of photographic paper up to objects while quickly exposing them to a light source. The process imprints the shadow of an object on the paper—“in the same way that the violent process of the bomb did,” he says. And he had to do all this at night in order to limit the papers’ exposure to light.

Matsuda doesn’t want his project to be defined by the nuclear shadows, however. He wanted to build off of them to create something new.

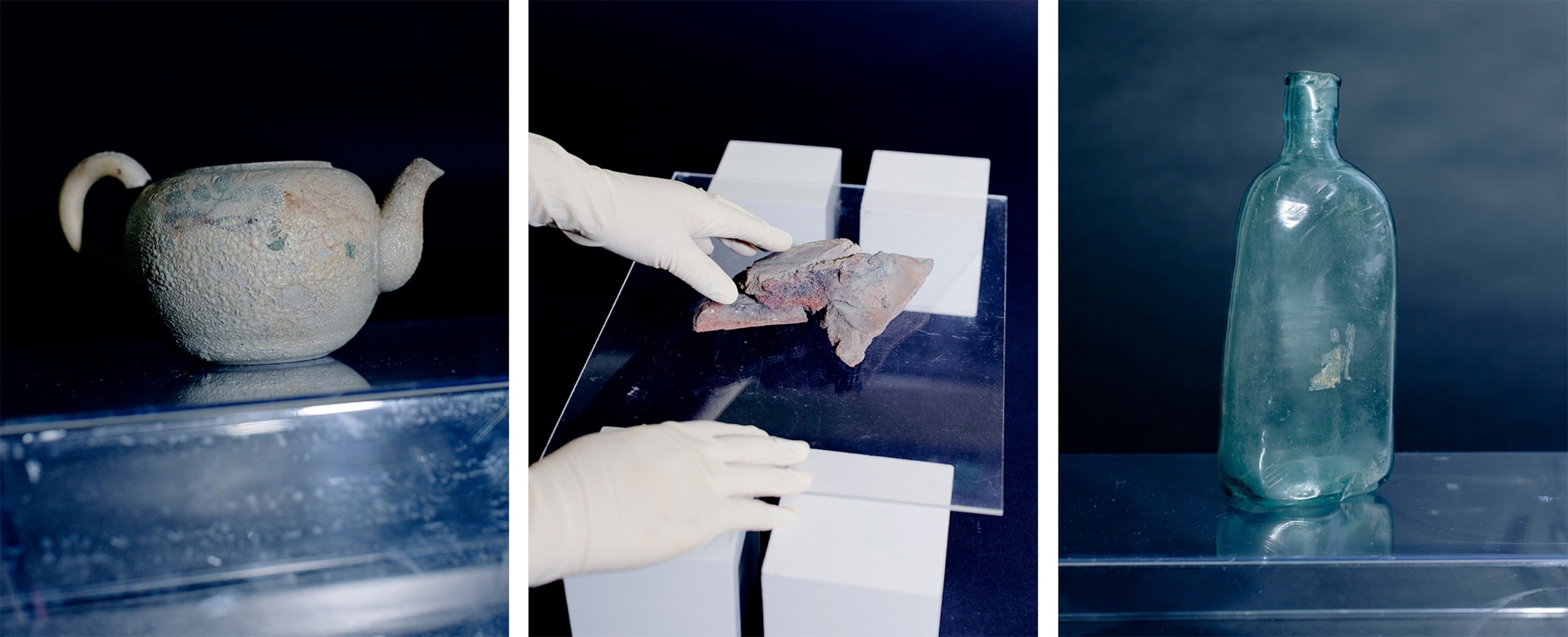

To that end, he chose to feature objects that survived the 1945 bombing. A gingko tree, a partially melted teapot––they underline resilience in the face of destruction.

Matsuda also chose sites with personal significance, including a shrine in Matoba-cho, the neighborhood where his great-great-grandmother had lived at the time of the bombing. He says he felt a “deep spiritual connection” to the shrine and created an image there as a way to honor her.

By traveling to Hiroshima to capture these images, Matsuda says it was a personal journey as well as an artistic one. “I’m trying to reestablish my own connections to the city because the familial ones have mostly been erased,” he says. “I was raised fairly Buddhist, and there’s this prayer and ritual connected with your ancestors. So it has been spiritually motivating for me to connect to them.”

Behind the scenes at the Hiroshima Peace Museum

"I felt a reverence and an emotional connection to the nuclear-bombed artifacts I photographed at the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum. I am looking for these through-lines, these living and nonliving things that existed before and after the bomb. I wanted to really sit with them, but that just wasn’t possible in a photoshoot like this. I had to move quickly and carefully, in the dark, to make the images in this unusual way. With this process, it feels like there is part of these special objects imprinted onto the paper–their melted forms, their resilient beauty, and the evidence of what they endured."