Space Archaeologist Wants Your Help to Fight Looting

Sarah Parcak, winner of the million-dollar TED Prize, hopes to equip an army of citizen-scientists to discover and protect ancient sites.

For years, archaeologists have waged a desperate global battle against the looting of ancient sites and the ransacking of humanity’s past. They have pressed government leaders to post police guards at major sites, crack down on the networks of antiquity smugglers, and issue red alerts on plundered artifacts.

But today American space archaeologist Sarah Parcak, winner of the $1 million TED Prize, announced that she will spend the money on developing a fresh approach to the problem—a cutting-edge computer technology for combating looting.

Working with a team of researchers, Parcak plans to turn the world’s children and adults into space archaeologists by developing an online program that makes use of satellite imagery and crowd-sourcing to record new archaeological sites and map looting activity. The resulting data will then be shared with archaeologists and government authorities, says Parcak, director of the Laboratory for Global Observation at the University of Alabama at Birmingham and a National Geographic Fellow.

“The big dream is that ultimately we will map the entire world," Parcak said. "You’d have a global alarm system where areas would glow red when they are being looted.”

Telltale Traces of Lost Settlements

Parcak is no stranger to innovation. As a young graduate student in Egyptian archaeology, she began analyzing high-resolution satellite imagery from NASA and other sources to detect traces of long lost Egyptian settlements. Through trial and error, she learned how best to identify ancient buried walls from certain chemical signatures in the soil covering these structures. By 2011 she and her team had discovered as many as 17 previously unknown pyramids and 3,000 ancient settlements in Egypt.

At that point her research took a dramatic turn. As Egyptians took to the street to bring down the government of President Hosni Mubarek in 2011, large numbers of looters capitalized on the turmoil and began digging up some of Egypt’s most important archaeological sites. Alarmed by the reports, the National Geographic Society asked Parcak to use satellite imagery to assess the scale of the damage.

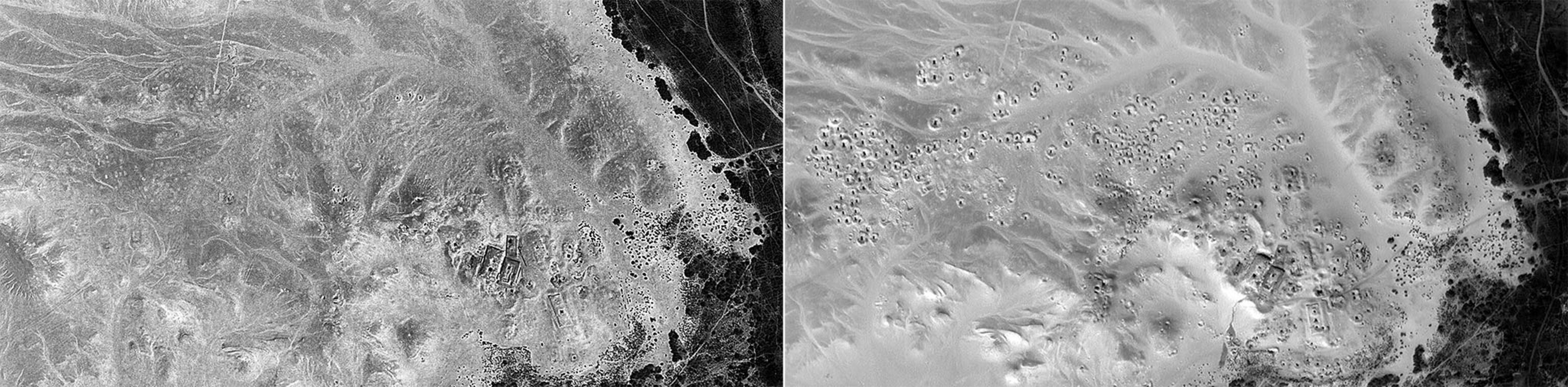

“That’s really what got me started in this area,” she says. Her study painted a clear picture of the destruction: Between May 2011 and the fall of 2012, the number of looters’ pits at two major sites—Saqqara and Lisht—increased by 520 percent.

For Parcak, the study was a call to action. Rather than just counting holes in the ground, she wanted to develop a new way to protect ancient sites. “The reality is we are losing the battle against looting,” Parcak says. “Archaeologists have limited resources, and we need to scale up big time.”

So when she won the $1 million TED Prize last November, she had a clear vision of what she wanted to do with the money: engage the public around the world in the process of archaeological discovery, and create a new citizen-science technology for mapping and protecting ancient sites.

Parcak is recruiting crowd-sourcing specialists to help design this technology. After logging on and receiving basic tutorials in what to look for, users “will be dealt a card, or a series of cards from a deck,” she says. Each card will consist of a small satellite image covering somewhere between 400 and 2,500 square meters of ground.

The reality is we are losing the battle against looting. Archaeologists have limited resources, and we need to scale up big time.Sarah Parcak, Archaeologist

Users will be given only a general idea of the location—perhaps southern Italy or northern Peru, for example—to protect the sites. They'll then be shown examples of what an ancient tomb, village, or looter’s pit would look like from space, and asked to look for these features on the dealt card.

Behind the scenes, Parcak and her team will share all the new data on looting activity with the relevant governments. In addition, she intends to compile maps of previously unknown archaeological sites and give them to archaeologists who work in the region.

"Democratizing Archaeological Discovery"

But there will be one hitch. The archaeologists “have to take the world with them when they dig the sites,” says Parcak. “They have to use Google Hangout, Periscope, or Twitter and make the process more transparent. Essentially what we are talking about is the democratization of archaeological discovery.”

If all goes as planned, the new program will go online by the fall. And by introducing school children around the world to the excitement of exploration and discovery, Parcak hopes to educate a future generation about the importance of archaeological sites, and the pressing need to protect the world’s cultural heritage.

“I think the only solution for stopping looting globally is to get people to buy into the idea that our human history is important,” she said.

Christopher Thornton, senior director of the Cultural Heritage Initiative at the National Geographic Society, says the ambitious project could make a major difference in what has long been a losing battle for archaeologists.

“I think Sarah has the right vision and she has gathered the right groups around her [to develop the project.] This is a huge opportunity to educate the public on things that we know about looting because we are deeply embedded in this world.”