‘I think I’m going mad’: A harrowing tale of the first Americans to summit Everest

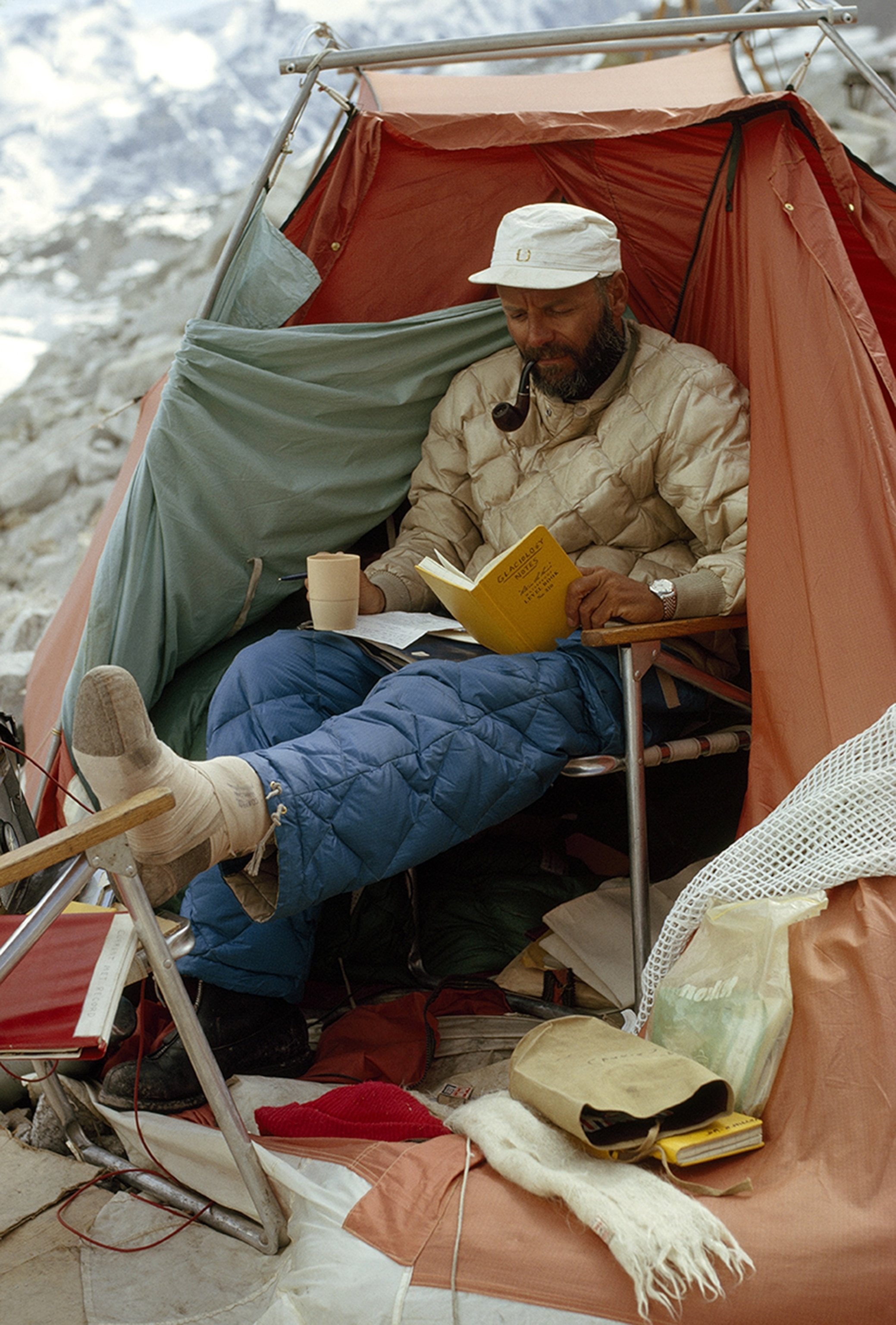

In May of 1963, National Geographic photographer and correspondent Barry C. Bishop was part of the first American team to summit Mount Everest. It was a feat that nearly drove the team mad, and one Bishop recounts in a cover story reprinted here.

“Lute, I think I’m going mad.” I speak through clenched teeth to Lute Jerstad, lying beside me in the two-man tent. For several hours I have been fighting a terrifying claustrophobia. We are alone at Camp VI, 27,450 feet up on the Southeast Ridge of Everest. I suppress a wild desire to break out of the cluttered tent.

As all climbers know, lack of oxygen produces weird mental effects. The thin air and the antibiotics I have been taking cause my claustrophobia—and a muddled sense of balance as well. Lying flat, I feel as if I am at an absurd and sickening angle. Nausea wrenches my stomach. Breathing is quick and shallow. By bracing myself semi-upright, I maintain some semblance of equilibrium.

Lute tries to make me comfortable, but without success. Finally, I turn the regulator and increase the flow of oxygen into my plastic sleeping mask from one to two liters per minute. The little extra helps. Oxygen is our most precious commodity and our lives depend upon how well we conserve it: I apologize to Lute.

Drifting snows have compressed the sides of the tiny tent, robbing us of a third of our floor space. We are trying to sleep amid a chaos of equipment-clothing, oxygen apparatus, medicines, photographic supplies. Outside, a shrill wind lashes the crest of the ridge.

Disaster threatens summit attempt

Tomorrow, May 22, is our big day, our try for the top. We both know that we will need every physical resource we can muster. And we both wonder if my illness will leave me too weak for the summit climb. We say nothing; consciously, we force the thought from our minds. At my urging, Lute takes a sleeping pill. Soon he rolls over in his cramped sector and drifts into uneasy slumber.

For me, braced in my awkward position, the hours pass like a slow nightmare. But the increased oxygen finally takes effect. Almost in command of myself once more, I too close my eyes and sleep.

At five o'clock I awake, feeling much better. Lute is already moving about the tent, melting snow on two butane stoves for some hot soup. Our extremely heavy breathing and the excessively low humidity at this high altitude sap the body of fluids at an alarming rate—sometimes almost a cup an hour.

Fifteen minutes later, Lute attaches a fresh gas cylinder to one of the stoves. A sudden whoosh, and a sheet of orange flame envelops the entire end of the tent. I smell Lute's burning beard. In one blinding second, the fire consumes my plastic mask. My eyebrows and part of my beard go with it. Dirty white smoke fills the tent.

Panic grips us. Lute struggles toward the zippered entrance. I try to smother the flames with a sleeping bag, but my legs are still inside and I can gain no leverage. The fire feeds greedily on the air in the tent, soon exhausting it. Our lungs ache.

I am groping desperately for a knife when Lute tears open the zipper and literally dives outside. His momentum is so great that he almost pitches down the steep slope toward the South Col. I am on his heels. We snatch the flaming stove from the tent, douse it in the snow. The fire soon dies in the thin air.

Choking and gasping, we sag on our hands and knees. Minutes pass before we can breathe with any semblance of normality. As we crawl back inside, we say nothing to each other. But we share the same thought. The omens are bad, all bad.

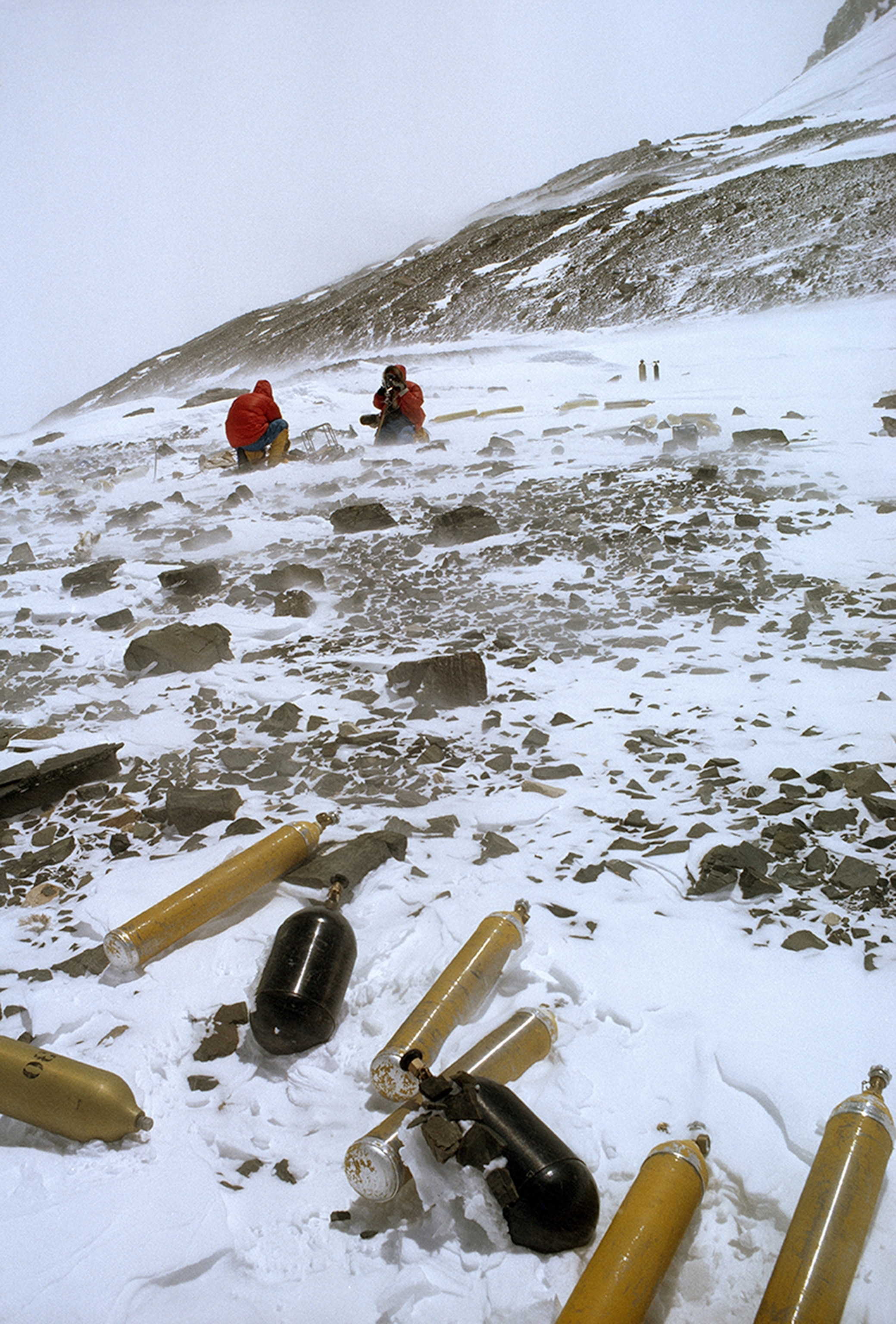

At five miles above sea level, every movement is laborious and exhausting. Within the smoky, reeking tent, we struggle into layer upon layer of clothing, finally sheathing ourselves in nylon parkas. Slowly we pull on boots and overboots, lash steel crampons into place, and attach our climbing rope. Stuffing two bottles of oxygen into our packs, we attach our regulators, pull on helmets and masks, and begin inhaling oxygen at the rate of three liters a minute.

Four liters a minute is regarded as the best flow for activity above 27,000 feet. But such a rate exhausts a cylinder in four hours. At three liters, a cylinder will last more than five hours; at two liters, eight.

Since each bottle weighs 13 pounds—and since weight is critical—the summit teams restrict themselves to two per man. Throughout the expedition, seldom do we enjoy the luxury of four liters.

The bad night and disastrous morning have thrown us two hours behind schedule. Not until 8 o'clock, still with no breakfast, do we slog upward at that monotonous, dreary pace mountaineers find necessary at such elevations. The weather is magnificent—windy but clear. Fluffy cumulus clouds cling to the sides of the surrounding mountains.

Heeding the advice of Big Jim Whittaker and Nawang Gombu, who had preceded us to the summit three weeks before, we traverse the southerly slope of the ridge. With Lute at the head of the rope that joins us, we pick our way for 500 yards across shattered, unstable rock flecked with snow and ice. Then we turn directly up a long snow slope. Our progress is slow, and I know that the night has taken a heavy toll. I am having an off day. And to have it now, of all times! Every climber has such days, but you always hope to be hot for the big ones.

Just before 11 o'clock, we attain the crest of the Southeast Ridge. From here we look down the 10,000-foot drop of the Kangshung face into Tibet. I take the lead from Lute and for another three or four hundred yards we follow a knife edge of hard snow.

The wind picks up and I feel like a novice tightrope walker as I fight to keep my balance. The fearful Kangshung face drops precipitously on my right; on my left, a steep half-mile below, lies the South Col.

Climbers buoyed by candy-bar lunch

Lute resumes the lead. Dead ahead we spy our first goal, the South Summit. It towers some 500 vertical feet above us. In an exhausting two and a half hours, we gain only 200 of those forbidding feet. At a rocky outcrop, we pause for the only food we take that day—a quarter of a candy bar apiece.

Ten minutes later we continue the aching upward plod. We inch along the line of contact between steep snow on our right and rock outcrops on our left. The slope tilts at a dangerous 40 to 45 degrees. We generally keep to the snow, but when it becomes difficult, we gingerly tread upon the bare rock, enjoying the best of two very tricky worlds.

At 28,500 feet my first cylinder of oxygen runs dry. Lute checks his and finds it almost empty. So we halt on a small sloping ledge to change bottles. Discarding the old cylinders, we lean back against the mountain.

Suddenly I trip over one of the empty bottles at my feet and fly out into space. Instinctively, I twist in mid-air. Hitting the slope face-down, I claw at the snow with hands and feet. I manage to stop.

I glance to my left and see Lute beside me, holding me with his right hand. He has jumped out after me, flipped on his belly, and grabbed. We crawl back up to the ledge, and lie there for a long moment.

"That could have been serious," Lute says.

I nod. Both of us have narrowly missed falling all the way into Tibet.

We continue, our packs lighter because of the discarded oxygen bottles. I feel spent, dull. One step...six long breaths...another step...again six breaths. Each pace requires almost half a minute. My entire body aches.

We cross hard, steep snow. Lute, in the lead, chops steps. We mount toward the South Summit, slowly, slowly.

An hour passes...another thirty minutes. I wonder if we will ever reach the summit.

Upward. Always upward. Foot by painful foot. Gradually, I become convinced that we will indeed go all the way. And at 2 o'clock, beneath a piercingly blue sky, we stand at 28,750 feet on the South Summit of Everest—our first way station. We lean into the heavy wind that buffets us with gusts of 60 to 70 miles per hour.

To the southwest my eye can trace our route up Everest from the Dudh Kosi valley. The midafternoon sun reflects off the metal roof of the shrine at Thyangboche, 15 miles away. Already we stand at a point 500 feet higher than any other mountain in the world.

Our oxygen situation becomes more critical by the minute. We know we must conserve as much as possible. Therefore we turn our regulators back to a flow of two liters a minute. The new deprivation is not immediately apparent. Our discomfort is so great, the going so hellish, that we perceive no difference.

Hillary photograph aids climbers

Atop the South Summit, Lute and I peer at the awesome route to the true peak. It rises above us in craggy, snow-scarred grandeur. Long ago we memorized this view from a photograph taken by Sir Edmund Hillary. We know it as well as we know the streets we live on. But somehow it looms steeper, closer, more forbidding than in the picture.

While on the mountain, all of us in the summit teams think of ourselves as intelligent and lucid. Only afterwards, in reconstructing our actions, do we discover how irrational we really were.

So it is that Lute looks down with dismay at a 30-foot vertical wall of rotten snow—our jumping-off-point for the North Summit. Unaccountably, he starts walking due west, down a small slope.

Later Lute explains: "I was a little bit spooked by this 30-foot vertical pitch. I thought that this couldn't possibly be the way. And I don't know whatever possessed me, but I suddenly took off down to the left.

"I walked 75 feet down the South Summit and saw some rocks, and I apparently thought I saw some footprints down there, and Barry all this time thought I was completely crazy. He just looked at me and shook his head and threw up his hands and didn't know where on earth I was going. I think he thought I was going to end it all right there.

“I got to the end of the rope and I realized that I had made a very foolish mistake, and I had to grind my way back up this 75 feet—which, at this elevation, is kind of tough."

With Lute back on the South Summit, we gird for the crucial assault. He leads the way down the nasty wall. With our goal so close, we move more rapidly now. Lute negotiates Hillary's Chimney—an upward cleft in the rock face—in beautiful style by climbing out halfway up and flanking it from the left. Finally we emerge above all the rock out crops onto the final summit cornice ridge. Here we trudge over bump after bump of hard snow. The intense winds force us constantly toward the unsafe overhanging edge of the cornice on our right; we concentrate on staying to the left.

I plod along with my head down. Seven full, gasping breaths now punctuate each step. I focus on my feet...lifting...placing...lifting...placing.

Suddenly the rope that ties me to Lute, 75 feet in front, goes slack. I look up as Lute raises his right arm. I know he has at last sighted the top.

A few more agonizing steps and I too see the American flag held taut by the wind on the summit. How the sight of it affected us is vividly expressed by Lute in an account he dictated after the climb:

"Just then we came over the last rise and there was that American flag—and what a fantastic sight! That great big flag just whipping in the breeze, and the ends were tattered. It kind of reminded me of the pictures I'd seen of this thing on Iwo Jima—the flag raising and everything. It was quite a sight.

"And we could see Jim's and Gombu's tracks from the chimney all the way to the summit; they were still there and you could see where the tracks went to the cornice and then ended where the cornice fell off between the two of them and then the tracks went on."

Lute coils in the rope as I come up to him. Arm in arm we then begin to trudge the last hundred feet to the summit. We are bone weary; our lungs suck wildly for air; thinking is a torment. But, if necessary, we would crawl to that flag.

What do we do when we finally reach the summit and flop down? We weep. All inhibitions stripped away, we cry like babies. With joy for having scaled the mightiest of mountains; with relief that the long torture of the climb has ended.

It is 3:30 p.m. The wind whips and tears at us as we perch precariously on earth's highest pinnacle. The American flag left by Big Jim and Gombu chatters in the gusts.

We cut off our oxygen-already low—and set about our tasks. Lute strikes his ice ax into the hard snow, anchors a motion-picture camera to its head, and shoots the first movies ever made from the top of the world. The ax shudders in the wind. Lute's silk-gloved fingers begin to freeze—quite literally—as he turns the camera's metal crank.

I take a series of still photographs. Movements are sluggish at 29,028 feet, and the pictures take a long time. Too long. My fingers too freeze badly.

The view is spectacular. To the north stretch the rolling brown hills of the Tibetan Plateau, crowned by range upon range of snow-capped peaks. Cloud banks some 10,000 feet below mask the east, but looming above them in the distance we see the Kanchenjunga Massif. India, to the south, lies veiled beneath a solid mass of clouds. The 22,494-foot summit of Ama Dablam that I had climbed two years before seems insignificant from the lofty eminence of Everest.

I reflect for a moment on the climbers who had pioneered the Himalayan peaks only a generation or two before. They had reached—or almost reached—these heights without oxygen, without any of the complex equipment we now deem indispensable.

In my mind's eye, I see them: Mallory, Irvine, the others who struggled so valiantly on these slopes. In puttees, Norfolk jackets, and jaunty felt hats, trudging doggedly into the thin, high, freezing air.

For 45 minutes we stay on the summit—seated in deference to the powerful wind that threatens to blast us back down the mountain.

We stare long and hard down the grim West Ridge, hoping for some sign of Willi Unsoeld and Tom Hornbein, our comrades who planned to assault the peak via that untrodden route. Our straining eyes see nothing. The ridge is empty.

Lute brought pictures of his family to leave, but he forgets to dig them out of his pocket. He also brought a New Testament given him by his parents that he had planned to place at the summit. But now he decides it is too good to leave on this desolate peak.

About 4:15, short of oxygen, we begin the descent. Life-giving gas hisses once more into our masks, but we allow ourselves a barely perceptible one liter a minute. The wind, blowing strongly still, stretches the rope between us into a taut crescent that arcs over emptiness beyond the crest.

Lute goes first as we traverse a section of the corniced ridge. He disappears around a bend in the undulating snow. The rope, stiffened by the wind, catches the edge of the cornice, cuts itself a groove, hooks the edge. Danger!

I shout into the 70-mile gusts, but Lute hears nothing. The fouled rope draws me inexorably toward the edge. I dive onto the snow and wriggle out on the cornice, attempting to free the rope. My face is just above the snow. But my weight is too much; a section of the cornice at my chest gives way. I have a sudden, hair-raising view of Tibet's Kangshung Glacier 10,000 feet below.

Scrambling back, I notice that Lute's continued forward movement causes the rope to cut ever deeper into the snow. I undo the knot that secures it to my waist. It whips up and away across the whiteness. Unroped, I parallel its route. I wait until the end of the rope, like a frozen snake, slithers free of the cornice. Then I re-tie it to my waist. Elapsed time: less than a minute. Not until I tell him back in Katmandu does Lute know of this tight moment.

We negotiate the chimneys, but barely. At the bottom of the last one, we both collapse onto the crumbly rock for a breather. When we push on, I notice that Lute is staggering. He halts, checks his oxygen equipment. He tears away a string that has been fouling the bladder. No gas at all has been flowing into his mask.

We allow ourselves a generous two liters to ascend the steep, perilous pitch angling back up to the South Summit. We thank God that it is the last climb of the day.

Eerie voices from above

Cautiously we ease down the sharp southeast slope. Our oxygen again cut back, our bodies drugged with fatigue, we stumble and fall. But we move steadily down.

Dusk falls rapidly. The inky Himalayan night will enclose us long before we can reach the relative safety of Camp VI. By day it is difficult enough to locate the tiny cluster of tents; in darkness it could prove impossible.

7:30. The last of the light reflects wanly off the snow. The sky is cold, moonless, black. Our feet grow colder as we lurch down the mountain.

I stop abruptly. Is it the wind?

"Helloooooo! Helloooooo! Helloooooo!"

From somewhere the sound echoes across the mountain, eerie in the enveloping darkness.

Lute stops too. We listen intently.

"Helloooooo! Helloooooo! Helloooooo!"

On Everest the wind speaks with many voices. It rises, it falls, it thunders. Sometimes it is the remote night cry of a sick child. But it is always the wind.

We hear a third "Helloooooo!" and this time it is unmistakably human.

Could it be Dave Dingman and Girmi Dorje, our support party, searching for us out of Camp VI? The wind drops and in the sudden stillness the cries have a bell-like clarity. They are floating down from above. Above!

Lute and I look at each other, elated. Willi Unsoeld and Tom Hornbein! They have made it up the West Ridge and across the summit! "Hello, hello," we bellow.

There follows a weird, wind-whipped dialogue. Willi and Tom are some 400 feet above us, descending from the South Summit. Sometimes wind swallows our loudest shouts. At others, we hear—again with bell-like clarity—Unsoeld and Hornbein speaking to each other in conversational tones.

Once a voice from above asks, "Why the devil don't they shine their flashlights?" We shout up that we have no flashlights. A little later both climbers call out that they have just fallen into a small crevasse.

"That's it," we answer. "You're on the route."

We had fallen into the same crevasse.

During the two hours we guide them down by voice, Lute and I hang exhausted over our ice axes. I feel what little strength remains in me drain away. My feet, warm and comfortable throughout the entire climb, now begin to freeze. I stamp ponderously in the snow. No help. The pain in my toes sharpens. Then, as it skirts the edge of agony, it dies in a merciful numbness. I recognize the classic sequence of frostbite.

At 9:30 two figures emerge from the darkness that has swallowed all of Mount Everest. It is a darkness so deep that Lute reaches out and touches the first climber but cannot identify him.

"Who are you?" Lute asks.

"Tom," comes the answer.

Then Willi Unsoeld arrives and drops wearily into the snow. The reunion is joyous but short. Our plight is precarious and we know it. With oxygen all but exhausted, and with Tom's expiring flashlight our sole illumination, we join forces to head down the mountain.

We feel our way with cramponed feet and ice axes down the knife ridge of snow that Lute and I had ascended 11 hours before. In our weakened condition we can barely tell one side of the ridge from the other. Yet amazingly, while each of us tumbles frequently, no serious mishap mars the descent.

Willi goads me to struggle on. "Another 25 yards... just 25 more!" Then he cajoles me into lurching still farther until we cover 50...75...100 yards I had considered impossible.

Midnight finds us below the knife ridge, but now the route becomes more complicated. Snow and rock out crops lie directly down from the ridge for several hundred feet. A sharp turnoff leads to Camp VI. We know that in the darkness our chances of pinpointing this turnoff are poor indeed. So, at 12:30 on the morning of May 23, we decide to bivouac until dawn.

We plunk down on a sloping outcrop of rock, too tired to prepare ourselves with any care for the coming ordeal. Our site is nearly 2,000 feet above the highest previous bivouac in history.

By this time Lute and I have slipped into a stupefied fatigue. My feet have lost all feeling and the tips of my fingers are following them into numbness. We curl up in our down jackets as best we can. With his frozen fingers, Lute cannot even close his jacket. He wraps it tightly and hopes for the best.

For the next five and a half hours we remain anchored to that rock. Willi and Tom occupy a spot where they can move a bit. Tom struggles out of his crampons. Then, with typical selflessness, Willi removes Tom's over boots, boots, and socks and warms the feet by rubbing them against his own belly.

I lie dazedly on my back, my feet propped up like two antennae. Almost too weary to care, I wonder how badly they are damaged. I try to wiggle my toes. I feel nothing. Knowing it is hopeless, I abandon the effort and slip into a fitful sleep. Once Lute's spiked feet jab my thigh. I awaken sharply.

Although the last oxygen has long since been drained from our bottles, the masks still protect our faces from the cold. The mountain has pummeled us cruelly; but, in this ultimate crisis, Everest shows kindness. For tonight there is no wind.

Lying there in our frozen bivouac, with the temperature at 18° below zero, I recall snug nights in my sleeping bag at Base Camp. I remember hearing the wind play like a mighty organ over the ridges of the summit pyramid, then 11,000 feet above. Now I am on those ridges and, miraculously, Everest has stilled—for this one fateful night—its raging gales.

Savage wind produces near-blindness

Throughout the hours of darkness I long for oxygen. My breathing is deep, fast, and painful. Lute's eyes ache from a series of small hemorrhages induced by the winds that plagued our descent. He can barely see.

My own left eye is similarly affected. So, during the ghostly morning hours, I gingerly open my right eye to peer about. Far away, over the plains of India, heat lightning etches jagged patterns beneath a layer of cumulus clouds. Yet, close at hand, the rocky mass of Lhotse stands invisible in the darkness.

Just before 4 o'clock, the outlines of neighboring peaks begin to take form. Slowly dawn overrides night. A gray tint suffuses the high peaks. As the sun rises, the gray assumes the character of merging water colors. It becomes golden; then pink tempers the gold, and the rich, glowing light cascades down the mountains. Then suddenly the sun is up. The swift, magic kaleidoscope of dawn hardens into the stark colors of day.

Stiff but rested, we treat ourselves to the luxury of waiting until the sun actually touches us on our rocky perch. Warmed, and with the renewed optimism that every dawn seems to evoke, we commence our descent with a few wry jokes.

Willi and Tom lead off, followed at an interval by Lute and me. They use our tracks of yesterday as a trail, and soon they are well on their way. I curse myself for stumbling as I did the night before. Again my sense of balance seems to have deserted me. Lute struggles to keep me upright. Thanks to him, none of my slips brings serious consequences.

We reel down the mountain as much by feel as by sight. Lute cannot focus either eye; I can use only my right one. Still, we have no trouble finding the spot on the snow slope where we turn east and traverse over the Southeast Ridge into Camp VI.

As Lute belays me around a rock corner, I experience a surge of joy. Two figures struggle up to meet us—Dave Dingman and Girmi Dorje, laden with fresh oxygen tanks. The rock still screens them from Lute. I turn to him: "Do you want some oxygen?"

Lute thinks I have finally and unequivocally lost my senses. He just looks at me. Then I add, "Because here's Dave."

As soon as our teammates reach us, we hitch up the oxygen bottles and turn them to two liters. In mere moments we regain our vitality and our minds become lucid.

During the night Dave and Girmi had climbed to 27,600 feet in a futile search for us. Girmi had elected not to use oxygen—a tremendous sacrifice at that altitude, as we well knew—to conserve the precious gas for us.

Dave and Girmi, scheduled to try for the summit that day, unhesitatingly gave up their chance in order to search for us. Now they escort us back down to Camp VI.

Safely there, we rest and keep Nima Dorje and Girmi busy melting ice for water. We have an insatiable craving for liquids. We toss down coffee, lemonade, tea, hot chocolate, and soup as quickly as the Sherpas can produce them.

Now begins the difficult withdrawal down the mountain. At 10 a.m., we set out for Camp V on the South Col. We descend at a slow, steady pace. Pemba Tensing greets us, and again we fill up on liquids. Then down over the Yellow Band toward Camp IV. En route we pause and break out our radio. Willi had already radioed from on top, but now our teammates learn that all four of us have succeeded—and that all four are alive.

Soon the descent takes on the air of a picnic. Although we are totally debilitated, our success breeds euphoria. At Camp IV, I strip off my down-filled boots and for the first time examine my frostbitten feet. The toes are dead white, hard, and icy to the touch.

We hope to reach Advance Base, Camp II, before dark, but twilight overtakes us. The descent continues by flashlight. And now our feet begin to thaw. Pain flickers along our heels and each step shapes a separate agony. Faces grow taut with effort. The pace grows slower and slower. Not until 10:30 do we stagger into Camp II.

The following morning, May 24, we strike Advance Base and retreat farther down the mountain to Base Camp. Once again aching feet affect us all.

At the top of the icefall we encounter a formidable obstacle. The ice at a key point has collapsed. But the Sherpas have rigged a Tyrolean traverse. Wrapping our legs around a rope and hanging on monkey-fashion, we slide down a 150-foot diagonal to the bottom of the ruined ice.

Dusk of that night finds us reunited at Base Camp. A party atmosphere prevails. There is much joking, much emotion. And, in a perverse way, we feel sadness that our great adventure is ending.

Dave Dingman, one of our physicians, had examined our feet at Advance Base; the expedition leader has radioed a request that a helicopter be dispatched from Katmandu to Namche Bazar to evacuate Willi and me.

In the expedition's last radio contact from Base Camp with the outside world, we learn that the helicopter will indeed come for us.

When the last of the expedition moves out of Base Camp, Willi Unsoeld, Lute Jerstad, and I travel on the backs of Sherpas. Four porters spell each other in carrying each man. By the end of the first day, a fierce rivalry springs up between the four carrying me and the four carrying Willi. Every suit able stretch of trail inspires a foot race.

The next day, traveling fast, we move through Pangboche and Thyangboche. At 5 o'clock in the evening we reach Namche Bazar. The helicopter is scheduled to arrive within two days. Willi and I will be evacuated; Lute will be able to walk in a few days.

I awaken at 6 o'clock the following morning and note that the sky is overcast. Surely today will bring no helicopter. I close my eyes and drowse. But 25 minutes later, the whirr of chopper blades snaps me rudely into consciousness. The copter has come, weather notwithstanding. I feel a pang of regret. The expedition is breaking up. Never again will we all be together on a mountain.

Willi and I go aboard, and by 9:15 a.m. the helicopter is buzzing over the gleaming pagoda roofs and old palaces of Katmandu. Our pilot eases the copter down into a paddy outside the pillared white gates of the United Mission Hospital, Shanta Bhawan. From a mass of friends, well-wishers, and news camera men, two slim, pretty women scramble down the slope into our arms. They are my wife Lila and Willi's wife Jolene.

We hobble into the hospital for baths, breakfast, and a thorough examination. Our toes, now blackened, are cleaned and dressed. A mechanic of the U. S. Aid Mission improvises a whirlpool bath for our feet from an oil drum and a kerosene heater.

Dr. Robert Berry and the hospital staff willingly work long, tedious hours to save our feet. Our meals are specially cooked each day in the home of Bob and Margie Berry. Members of the American community, including Ambassador and Mrs. Henry E. Stebbins, send food. Books, cookies, candies, and other delicacies pile up in our rooms.

All the way from Washington comes Dr. Melvin M. Payne, Executive Vice President of the National Geographic Society, bringing Dr. Eldred D. Mundth, Navy frostbite specialist, to assist Dr. Berry with counsel and the latest drugs. I learn that the U. S. Naval Attache to India and Nepal is sending a military plane with a built-in bunk to evacuate me to New Delhi. Willi stays behind for his Peace Corps work in Nepal.

In the quiet of the hospital, I ponder the lessons we have learned. Everest is a harsh and hostile immensity. Whoever challenges it declares war. He must mount his assault with the skill and ruthlessness of a military operation. And when the battle ends, the mountain remains unvanquished. There are no true victors, only survivors.