Being Kidnapped and Losing a Finger Couldn't Stop This Climber

In his new book, American rock climber Tommy Caldwell shares how to overcome obstacles, break records, and keep a clear head.

In 2015, Tommy Caldwell and his climbing partner, Kevin Jorgeson, finally achieved what many believed impossible: the first free ascent of the Dawn Wall on El Capitan, Yosemite. Using ropes just to catch their falls, they pulled themselves inch-by-inch over 19 days up the 3,000-foot rock face.

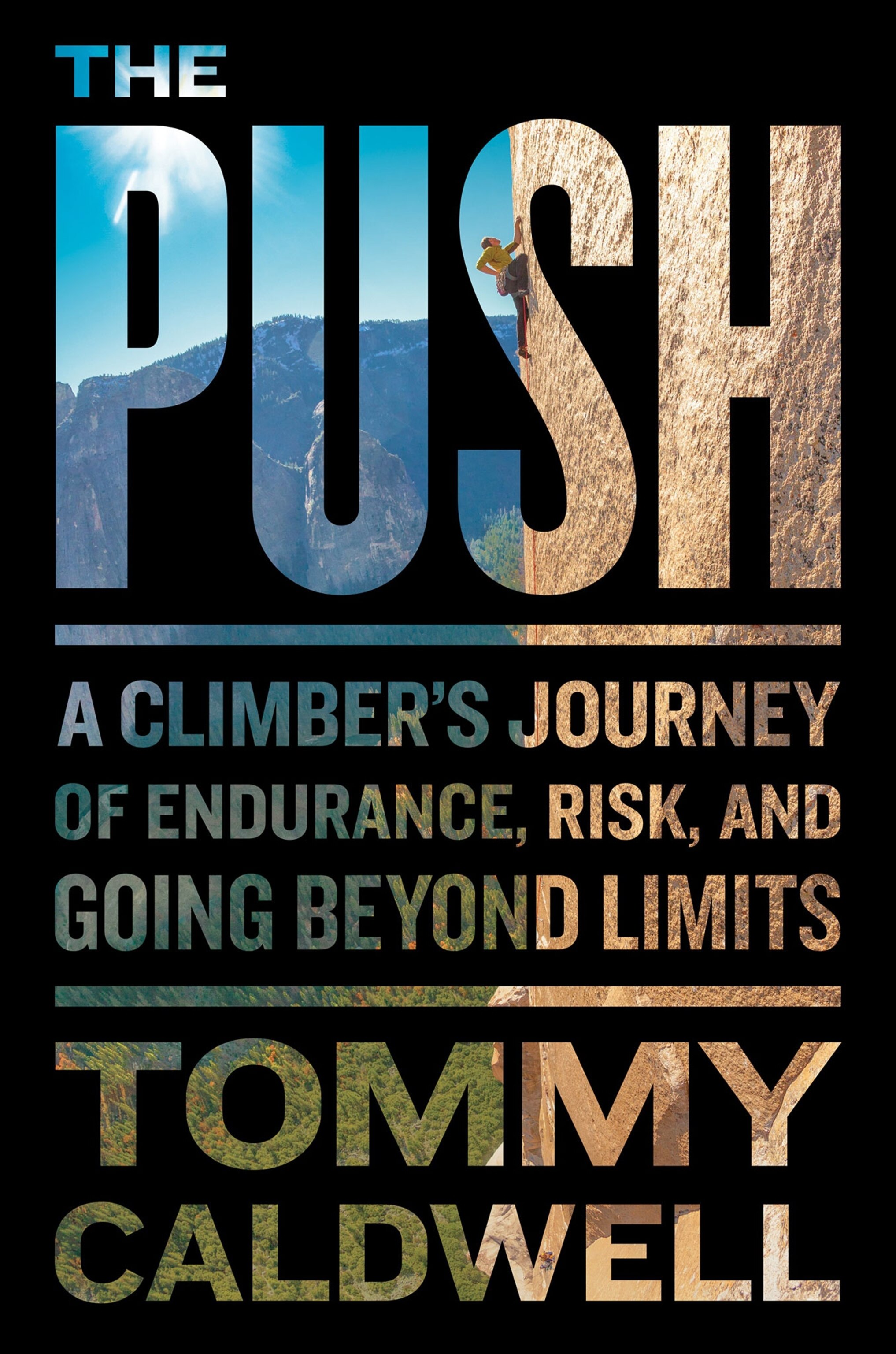

That thrilling story forms the backbone of his new book, The Push: A Climber’s Journey of Endurance, Risk, and Going Beyond Limits. But there is much here for non-climbers, too. Caldwell reflects on a lifetime of challenging himself as well as the horror he felt when he thought he’d killed a man during a terrifying kidnapping ordeal in Central Asia.

Speaking from his home in Estes Park, Colorado, he explains how free climbing is like ballet or gymnastics, how his wife and family handle the risks of his occupation, and how, ultimately, the difference between success and failure comes down to the skin of your fingertips.

For most people, including me, the idea of hanging onto a vertical wall of rock 3,000 feet high by your fingers and toes is the stuff of nightmares. Am I missing something?

[Laughs] We’re all wired a bit differently. Things that some people find absolutely terrifying or horrible can be appealing to others. Climbing is definitely that way. Anybody who gets involved in it is going to find out that it’s not as terrifying as it seems from the outside. It’s this beautiful way to experience nature in our most dramatic landscapes. You get to know people well when you do something that’s slightly scary together and climbing is something that seems scary. But ropes are strong if you use them, and you can make it quite safe. Most of the climbing that I do is that way. It’s a game, played out in a very exciting environment. Climbing is a constant process of taking what looks improbable or impossible and breaking it down to the elements, therefore making it possible.

In 2015, you and your partner, Kevin Jorgeson, became the first climbers to “send” the Dawn Wall on El Capitan, in Yosemite. Why was that climb such a challenge—and why were you so obsessed by it?

I’d spent nearly 15 years of my life’s climbing focus, mostly on this one wall, El Capitan. It’s the most dramatic, historical rock face in the world, without a doubt. I’ve climbed all the existing routes that had been done in the past, established a bunch of my own, and still have endless curiosity for how far I can take it physically and mentally.

The Dawn Wall appealed to me because it was bigger, blanker, and looked improbable. But when I first went up there and mapped it out, I didn’t realize I would get obsessed enough to spend seven years on it. I gave up several times but it kept getting under my skin.

In the end it was less about the feats of accomplishing it and more about the day-to-day life style it provided. I loved going up the wall every day, living this very intentional life of pursuit. It looks unclimbable when you’re up on the face: this sheer 3,000-foot rock fall, with what looks like nothing to grab onto. Only the very tips of your fingers and toes are making contact with the wall.

Ultimately, it came down to our skin. You try to climb as delicately as possible, pulling on holds lightly, so you don’t tear your skin. But the holds were often so sharp they would wear out our fingertips. We’d start bleeding and get cut. When that happens, you can’t hold on to these razor-sharp holds anymore, so you have to pay very close attention to the skin on your fingertips. We were eating things that we thought would fuel our skin, from the inside, and applying different lotions and trimming our nails. We would take sandpaper and smooth off the little burrs on our skin so they wouldn’t catch and tear. It was a seven-year process of figuring out how to do everything properly.

Your interest in climbing was spurred by your father. Tell us about your early life—and how his influence shaped you.

My dad was an early adopter of the idea of adventure parenting. Back then, nobody did that. Everybody thought he was a lunatic for taking me out in the mountains, changing my diapers in a snow cave when I was three years old! [Laughs] Summers, weekends, any possible moment, we were always going off climbing. We did it because that is what he loved. It also had the side benefit of helping a small, socially shy kid build confidence. It was quite extraordinary and shaped my life. I’m a very energetic person and I’m lucky enough to live in this very engaging world, with a community of people that are doing something cool.

It has been said of your friend and colleague, Alex Honnold, that he is such a fearless climber because he is not afraid of death. How do you manage fear—and risk?

I don’t know if I have a great answer to that. Some of us process risk and fear rationally; others process it emotionally. For me, it has to do with being out on the battlefield starting at a very young age, experiencing very scary things and living through them. I process things very rationally. I don’t have an emotional reaction to things like heights.

Alex is the same. It’s one of the reasons we enjoy climbing together so much. There’s not the heaviness, the weight of possible death when we climb together. We just go out there, thinking: Man, we’re doing something so amazing! But his tolerance for risk is much higher than mine. He has this mental armor when he risks things, unlike anybody I’ve known. People have scanned his brain and—this is a known fact—he does not have the hormonal release that creates epinephrine. So he doesn’t react as severely to scary things.

Several times, you compare rock climbing with gymnastics and even ballet. Can you develop that comparison for us?

Movement across rock is very fluid and is something we spend a tremendous amount of time trying to perfect. On climbs like the Dawn Wall, we’re trying to climb a piece of rock that is above our ability level. So we practice and train ourselves until we can perform it with absolute perfection. That’s what a musician or a ballet dancer does. It creates flow and it’s a magical place to be. You feel invincible and totally confident. Your brain is so occupied and so perfectly aligned that everything seems to work and possibilities open up. That kind of flow is something I constantly crave, having experienced it a few times in my life.

In your twenties, you travelled to Kyrgyzstan, in Central Asia, to climb—and ended up being captured by Islamist militiaman. Tell us the story, and how it affected you.

I was 22 years old, on my first big international climbing expedition. There was a mountainous region in Kyrgyzstan, very much like Yosemite, in a remote location about 30 miles from the nearest road. A group of four of us, all quite young, went there looking for adventure. But we got more than we bargained for.

In the year 2000 it became this opium-trade-political situation. We were taken hostage by a rebel group called the Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan and held for six days. Eventually, our captors made us abandon all our supplies, food, and warm clothing. We lost between 15-20 pounds each and were on the verge of hypothermia. It was a life-changing moment, far beyond anything I’ve ever experienced, or could have imagined.

It affected me in tons of ways. The very first words I wrote in this book describe the moment when I felt I had to take matters into my own hands and I pushed our remaining captor off a cliff and ran for safety. It was so intense I’d never let myself process that. So part of writing this book was wanting to get back there and understand more about it.

It turns out I didn’t kill him. He fell out of sight in the darkness down this mountain. But for a while I thought I had. What bothered me at the time was, what brought me to that place? What was it in me that was capable of killing someone? Even in that moment, we didn’t see him as an evil person. He was the enemy in one way, but he was also a victim of circumstances. Who is to say, if we were raised on the poppy fields of Afghanistan, that we wouldn’t have found ourselves in the same place?

You have also climbed in Patagonia (and named your son after the Fitzroy Range). What draws you to that part of the world?

I still have this intense need for adventure. Patagonia is great for that: a dramatic and unbelievably beautiful place. We call it “Alpine Light.” There are 4,000-foot granite spires, with crazy snow and ice mushrooms on top of them. It’s a historical place and some of my most magical climbing experiences have happened there.

It’s way more dangerous than climbing El Capitan, where the rock is solid and there’s no snow that can fall down and hit you and you are firmly attached to the mountain. Alpinism is way, way more dangerous. But that environment is so utterly beautiful; it changes you when you spend a lot of time down there.

When you reached the summit of the Dawn Wall, Melissa Block from NPR calls you; satellite trucks are parked at the base of the mountain. How do you keep your head clear from all that media hoopla for what can be life-or-death climbing decisions?

In some ways the media attention is not surprising. Climbing is an exciting lifestyle sport that connects with people. Dreaming big, plus this thread of brotherhood and camaraderie, inspires other people the same way it inspires us. But it’s something that didn’t exist in our world in the past. It used to be that you went out with your buddy and had this pure mountain experience. That still happens. In Patagonia you don’t get cell phone service until you get to the end of your trip. In places like El Capitan, though, you get great Internet service on the wall and there are people in the meadow watching you with telescopes. It’s very different.

You are now married and have a child. How do you square family life with your climbing? And how does your wife cope with the possibility that every time you set off, you might never come home?

Great question! I’m all about finding the balance. I’m looking for climbs these days that I’m relatively certain I will live through, and shying away from big alpine climbs that are very dangerous. I climb with a rope all the time. And a lot of these trips are quite safe, so you can bring the family. I just got back form a two-month trip in Europe with the kids and we were out at the boulders with them every day. The first two years of my son’s life were on the road. He learned how to count in five languages and became very worldly. So it’s a great education.

The risking my life part is the hard one. [Laughs] My wife is always asking me about the risk, how far am I pushing it, trying to get me to think about doing safer kinds of climbing. But she loves climbing herself. She spent 10 days up on El Cap with me at one point. She understands my climbing lifestyle. And she’s actually more of an advocate for our kids getting into climbing than I am. So it works pretty well.

Simon Worrall curates Book Talk. Follow him on Twitter or at simonworrallauthor.com.