Female Helicopter Pilot Took on the Taliban—and the Pentagon

After receiving the Purple Heart and Distinguished Flying Cross, Maj. Mary Jennings Hegar fought for the right to fight.

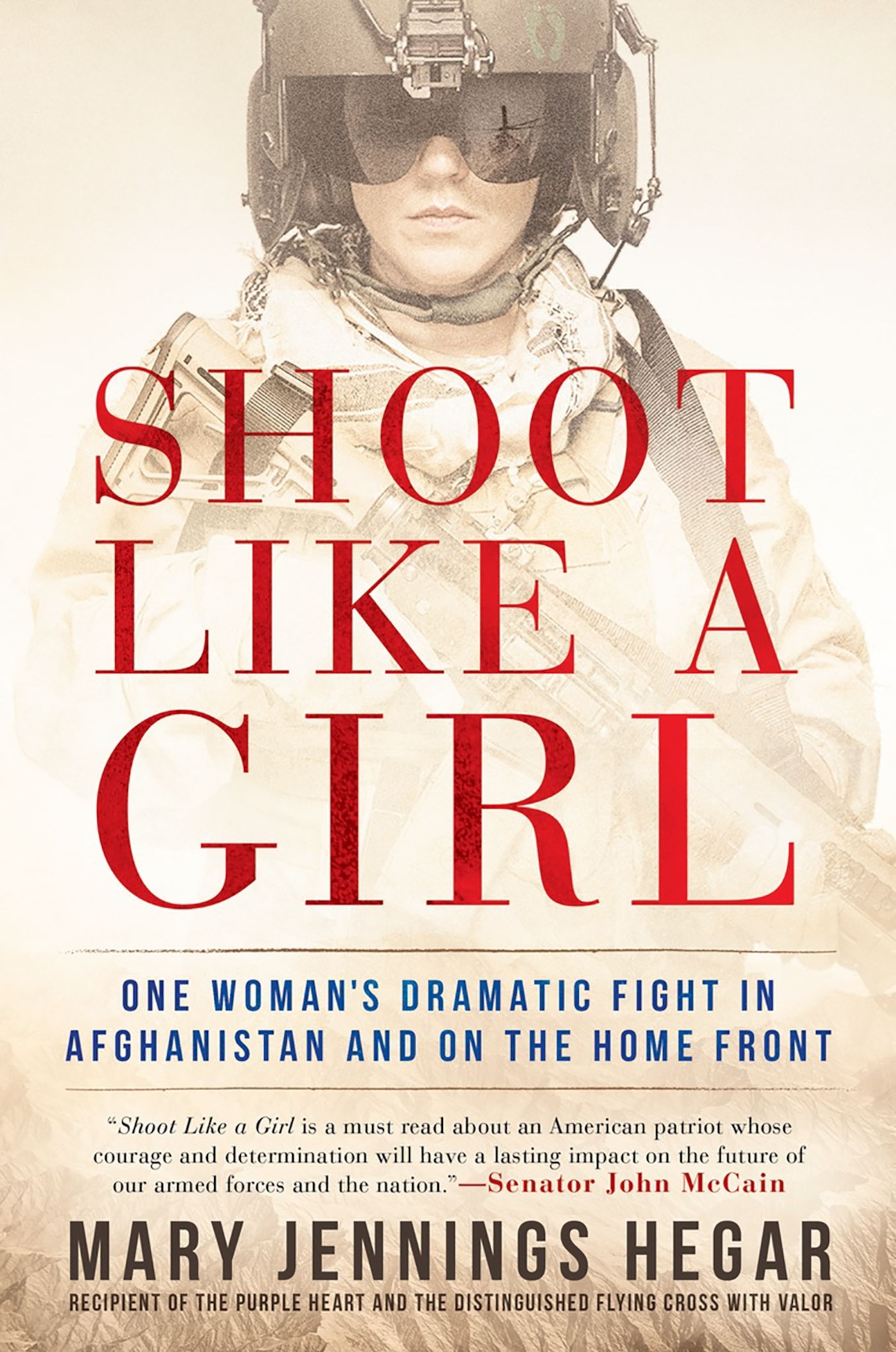

Mary Jennings Hegar, a former helicopter pilot for the U.S. Air National Guard, is only the second woman, after Amelia Earhart, to get the Distinguished Flying Cross with a Valor Device. So it’s not that surprising that Angelina Jolie is in talks to play Hegar in the movie version of her new memoir, Shoot Like A Girl.

When National Geographic caught up with Hegar by phone at her home in Austin, Texas, the Purple Heart recipient explained why she sued the Pentagon, how she would never have become a pilot if her mother had not left an abusive husband, and how, in 2009, in Afghanistan, everything she had prepared for came together when her chopper was hit by the Taliban.

The vast majority of pilots are men. When—and why—did your dream of flying combat helicopters begin?

I never dreamed to be a fighter pilot, because those guys are jerks. [Laughs] I wanted to be a combat helicopter pilot after seeing Han Solo in Star Wars. I never wanted to be Princess Leia. A lot of people ask why I don’t fly for the airlines now. It’s because of the rebel in me that doesn’t like rules. I don’t want the FAA [Federal Aviation Administration] telling me what altitude to fly at. I want to fly on my own. So helicopters were a natural fit for me.

I was also always a bit of an adrenaline junkie. If you couple that with being raised with a real sense of duty and patriotism, then being a military combat pilot made sense. It was a good description of who I was, at heart and soul.

Did your parents think you were crazy?

No, that’s the beauty of the way that I was raised. Nobody ever said, “Girls can’t do that.” And as I got older, in high school, I started pushing toward that dream.

You write, “I credit a lot of my life’s success to my mother’s courage in getting us away from my biological father.” Talk us through your childhood—and how it affected your dream?

My dad was an entitled, little rich boy who got into drugs and was very physically, mentally, and emotionally abusive. I don’t remember him being physically abusive to me because I was little and my mom protected me from a lot of that. I remember watching as he pushed my mom through a plate glass door. My sister was hitting him, trying to get him off my mom. He chased her around the house and pinned her up against the wall by the throat.

There was absolutely nothing I could do about it. I was four or five, sitting by the fireplace, crying. A recent lightning bolt was when someone asked me whether that was why I got into rescue. And I do think feeling so helpless as a child is a big part of my make-up—my warrior spirit and drive to protect people. I devoted myself to becoming as strong as possible. I went into martial arts, was always a fighter and an athlete. I did fire arms and felt comfortable with knives. I’m not a violent person, but I’m a capable person. I’m never looking for a fight. But I’m always ready for one.

Even though you were top of your class, as a woman in a man’s world you were subjected to all sorts of sexual harassment and discrimination. Tell us about the culture of the Air Force—and one particularly odious experience at the hands of a military doctor.

At the time I got my first flight physical, only one man had ever put his hands on me or seen me naked and that was my husband. I always went to a female gynecologist and received my pelvic exam before my flying class physical because most flight surgeons are men. I would show up at my physical and hand him the results of my gynecological exam and they would add that to the file. This guy had a god complex, which isn’t uncommon in the surgical field, and he acted on it in an insidious way. I stood up to him and said, “I don’t understand why you feel the need to give me an extra gynecological exam that I don’t need, especially because you are not a gynecologist.”

He threatened to fail me from my flying class, saying that I was psychologically unfit to be a pilot because if I was so distraught over his giving me an exam, what would I do if I became a POW and was raped?

This should tell you where his mind was, drawing a parallel between the gynecological exam he was about to give me and rape. In hindsight, if I had known what he was going to do, I wouldn’t have sat there and taken it. But I didn’t know. I thought it was going to be a regular gynecological exam. He was a doctor, a professional. I could trust him. So I submitted to the exam, and it was horrific.

You liked to blow off steam on the shooting range. One of your instructors complimented your marksmanship by saying, “Congratulations. You shoot like a girl.” It wasn’t an insult, was it?

It was a compliment! [Laughs] I’m not a big fan of dealing with stereotypes because I think everybody’s unique and I have met plenty of people who have bucked their stereotypes. But there are things that women are physiologically better suited to. Being a helicopter pilot is one of them because we tend to be able to multi-task better because of the way our brains work. We are also able to handle G-forces better because our bodies are built for childbirth, with lower body and ab strength.

We’re also really good marksmen for several reasons: center of gravity, respiration, and heart rate. Shooting is also a mental game and if you get inside your own head too much and put too much pressure on yourself, you won’t do well. A lot of guys feel they have to prove their manhood and worry about who is watching them, whereas women are just trying to do the best they can and beat their last scores.

It was during your second mission to Afghanistan, in 2009, that the book’s central incident occurs. Talk us through that day on June 29th—and how it represented your ultimate challenge.

Our motto is “These things we do, that others may live.” We live that every day, and I believe in it with all my heart. Being a pilot fulfilled my need for adrenaline and patriotism. The fact that we were saving lives made it especially gratifying.

On that day, we flew in to pick up three urgent American patients from a convoy that had hit an IED. The enemy had set up what they call a search and rescue trap where they purposefully injured someone hoping that a helicopter will come in that they can attack. We didn’t know, so we took a lot more damage than we had expected to. The helicopter was disabled, and I took a round through the arm and leg. It bled a lot but didn’t disable me. The aircraft had been hit so much that we were losing fuel, so we had to execute a hard landing two miles from the convoy.

The enemy forces came and started engaging us. We were on the ground holding our perimeter for about 20 minutes before the two army helicopters supporting us said they had to leave because they were out of gas and bullets, but that they could land next to us and we could jump on to their skids and they could take us out that way.

As I was running out to the helicopter, positioning myself on the skid, I saw some flashes of gunfire toward my crew, who were trying to get the patients over to the other aircraft. That really pissed me off! We were trying to save lives and, a lot of times, the lives we were trying to save were locals. In this instance they were Americans, but we got shot at a lot trying to save their own people. So I started firing back and, as the aircraft started to lift off, I continued to fire.

Were you scared?

I’m often tempted to lie and say I was scared. [Laughs] But I wasn’t. I’m an adrenaline junkie and I was living my calling; it’s where I was supposed to be. I was very composed. I knew exactly how to respond and never felt fear. I don’t know if it would have been different if I’d had kids. But I was doing what I was trained for and was happy to be there because I was with people I cared very much about.

You eventually took part in a lawsuit about discrimination in the forces that came to be known as Hegar v. Panetta. Why was that case so important? Did you feel nervous about effectively suing your boss?

Some people think it was me versus the Pentagon. But it was not like that! I partnered with the ACLU and the majority of leaders in the military believed this was best for military effectiveness. It was a military issue, not a women’s rights issue. But it also had the benefit of being the right thing to do for women’s rights.

Would you describe yourself as a feminist?

Yeah, I’m absolutely a feminist. [Laughs] I think that word gets demonized. If by “feminist” you mean being bold enough to think I’m the equal of any man I come up against and be willing to fight for other women to be treated that way, and be paid the same money for the same jobs, then, yes, I’m a feminist and I’m proud to be one! My husband’s also a feminist and so are a lot of the guys I’ve worked with.

The lawsuit was important, I thought, as a way to help Secretary Panetta have more ammunition in his pocket in order to defend himself when he repealed the ground combat exclusion policy, which barred women from being assigned to units whose primary mission was to take the fight to the enemy, like the infantry or special forces. The lawsuit put pressure on the Department of Defense to do it more quickly. But it was a joint effort of a lot of the leaders in the military.

You write at the end of the book, “people will always be afraid of change. Just like when we integrated racially or opened up combat cockpits to women.” What does the future hold for girls with a dream like yours?

I recently heard Bob Marley talk [in a documentary] about how he dreamed about a day when we would view people with different color skin in the same way that we view people with different color eyes. I hope that we can get there with men and women. Gender is a part of who you are but you should withhold your judgement of that person until you see what their capabilities are. Hopefully, that day will come when people will look at a woman and not let that inform their opinion of her until she starts doing her job.

I’m doing the things I’m doing for my daughters and the younger generation that is coming up behind me. The women who came before me did a lot and I owe them that. I need to pay it forward and do something for the women of tomorrow.

This interview was edited for length and clarity.

Simon Worrall curates Book Talk. Follow him on Twitter or at simonworrallauthor.com.