Adrift in the Atlantic, Missing Gear Takes an Unexpected Journey

A National Geographic engineer had accepted that his underwater camera trap was lost in the ocean. But three years later, he and his colleague got a call.

Alan Turchik has what some would call a dream job. He's a mechanical engineer for National Geographic and spends his days designing and constructing equipment for the world's best photographers, filmmakers, and scientists to use on research expeditions all over the globe. When he's not in the shop, Turchik is outside—usually at sea, but sometimes in the jungle or aboard a plane—testing his creations to make sure they actually work.

They usually do, but not always as planned.

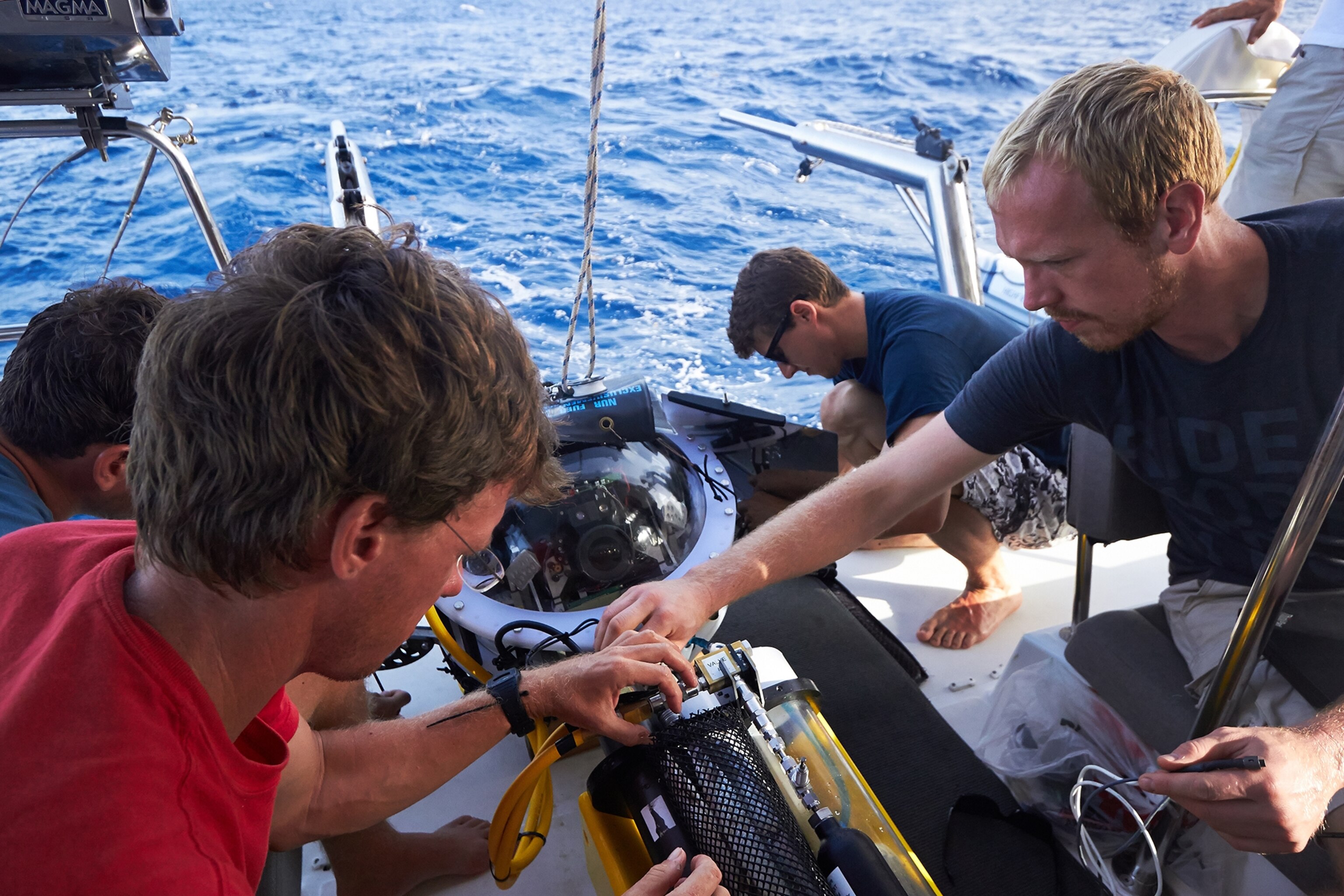

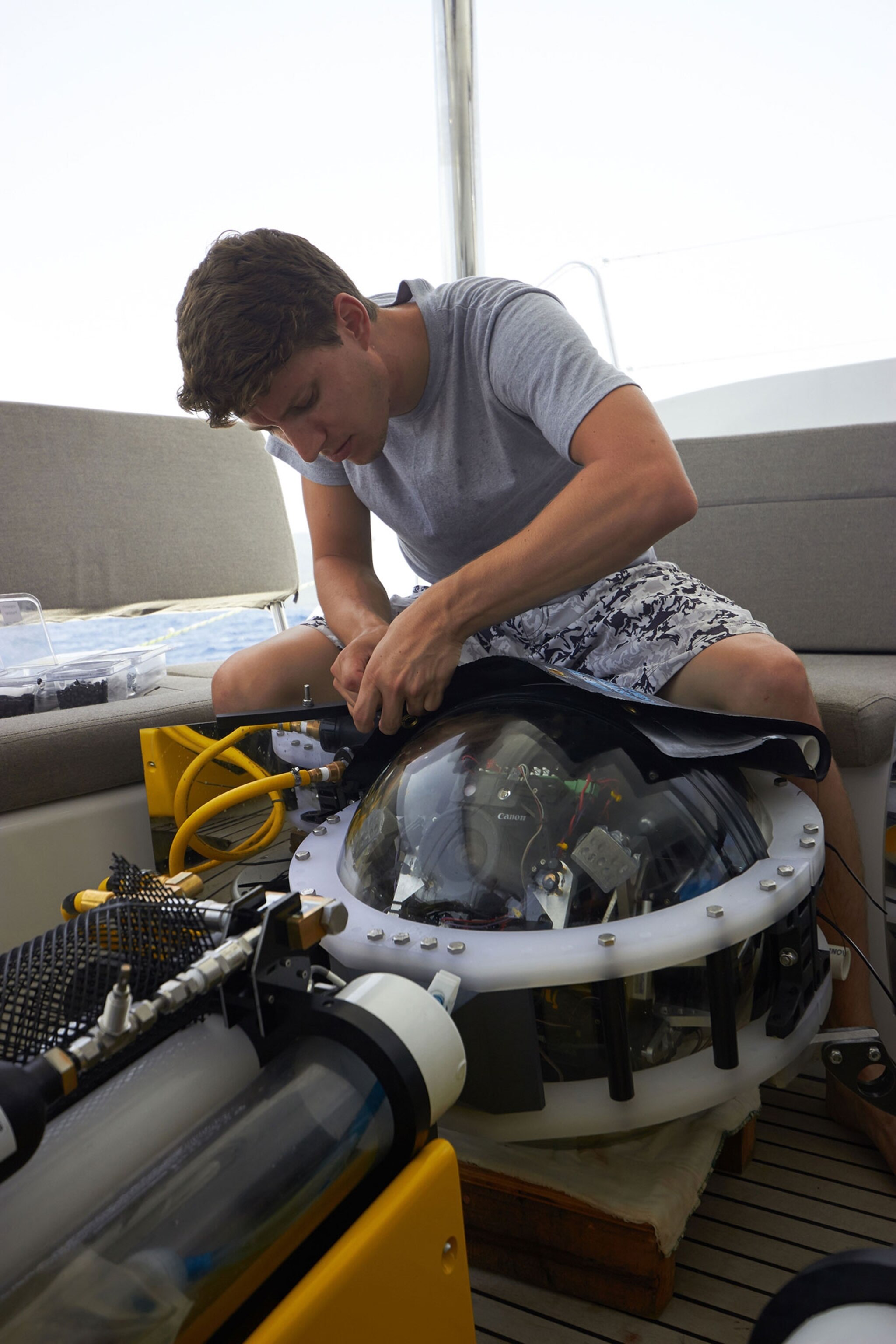

In April 2013, Turchik and some fellow engineers were on a boat off the coast of Miami, rain pelting down. They were testing their two Driftcam prototypes, each a 200-pound behemoth of metal, glass, plastic, and mirrors, each built specifically to record video of the ocean's “twilight zone,” a little-explored area about 600 feet below the surface. Because of their heft, the Driftcams had to be hoisted overboard by crane. Because of scheduling, the job had to be done at night.

Turchik's team believed the devices could float and record video for three hours in the twilight zone (also known as the “deep scattering layer”). After that, the Driftcams would begin to ascend while emitting GPS signals so the team could locate and retrieve them. That was the idea, anyway.

But the signals were weak, and the Driftcams were, well, drifting. The dark of night didn't help. “It's not a perfect science, picking up the signals,” says Turchik, “especially because they're moving targets.” But the team continued to search, figuring they'd find the Driftcams and return to shore soon.

Then the driver informed everyone that the boat was nearly out of gas.

With the Driftcams still in the water, the team turned back. They wondered if the equipment had gotten caught in the aggressive Gulf Stream current, and debated what to do. But it wasn't an easy decision. “We spent a year making those things,” says Turchik. “They were worth about 40 grand. We didn't want to lose them, especially since they were our prototypes.”

So he and his colleague Eric Berkenpas decided to rent a car and chase the Driftcams up the coast until they captured them. Every hundred miles they'd stop at a town and charter a boat. It was expensive, and felt futile. After a few days, Turchik and Berkenpas hired a plane to fly them low over the water. “We flew in a pattern as big as we could in the area where we thought they might be,” says Turchik, “but we didn't hear or see anything.” So they gave up.

Back at work in Washington, D.C., the team built two more Driftcams. They later deployed—and retrieved—them off the coast of Puerto Rico, and succeeded in capturing footage of the deep scattering layer. But they still thought about their long-lost prototypes, especially when a phantom signal would come through and they'd plot the location on a map, just for fun.

Nearly three years passed. Then, last June, Turchik's boss, Kyler Abernathy, received a bizarre call on his satellite phone. “I am French,” the caller said. “I am behind the others.” Abernathy assumed it was a prank. Then, an email appeared: “I just found at 32˚ 20N 48˚ 44W one of your ball in good condition. Inside, a SONY HDR.XR520. Do you need it?”

The messages were from a man named Eric Visage, a Frenchman who sails from southern France to Antigua twice a year. Turchik learned that when Visage had been sailing, his dog started barking at a sea turtle bobbing around in the water. Visage noticed that the sea turtle had “a friend” that turned out to be a large glass ball, which he pulled out of the water to inspect.

That's when he noticed the “National Geographic” sticker, along with a note to contact Kyler Abernathy if misplaced. The stickers had almost completely faded, but Visage could still make out the faint information.

Turchik and Visage made arrangements to meet at a marina in Toulon, France. The two hadn't spoken at length, and Turchik wondered if Visage would want some sort of reward. But that wasn't Visage's plan at all. In fact, after meeting Turchik, he offered to take him on a sail to the nearby island of Porquerolles, where they drank wine and ate in the shadow of a medieval castle.

With most of the Driftcam intact (a large portion had fallen off during its three-year Atlantic odyssey), Turchik flew back to D.C. and went directly to the shop, anxious to review the footage that had gone missing for so long. When images of jellyfish and tiny marine life began swimming across the screen, he felt vindicated. “It was amazing,” he says. “Plus, now I've got a really good bar story to tell.”