This Robot Could Make Exploring Oceans Deeper, Faster, and Cheaper

The undersea research submarine, built from scratch in less than a year, can capture ultra-high-def images of ocean realms.

Wendy Schmidt couldn't contain her grin as she watched the robot rise from the bottom of the saltwater tank at the Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute in Moss Landing, California.

It was the first test run of SuBastian, her custom-built remotely operated vehicle (ROV).

The underwater robot belonged to the Schmidt Ocean Institute (SOI), a nonprofit organization that Schmidt co-founded with her husband, Eric, executive chairman of Alphabet, Inc. (the parent company of Google).

The Schmidts created SOI in 2009 to speed up communication of marine research among scientists and the public, after they discovered that scientists were faced with too many unknowns about the ocean—thus making it harder to protect.

As part of that mission, the couple launched a project to build an unmanned robot that would inspire innovation in machine design, be created entirely around scientists' needs, and be ready to test in about a year—a tough request on all fronts.

SOI initially considered building a vehicle that could go deeper than the ocean’s average depth of 2.3 miles, but the added range would have required more time and detracted from SOI’s goal of communicating science faster.

SuBastian "gets us producing science data in a year and a half,” says Eric King, SOI’s director of marine operations.

To build SuBastian in the short time frame, SOI brought in an international team of engineers and designers, who also had to construct an entire shop from scratch to support the build. Two members, lead electrical engineer Nic Bingham and project manager David Wotherspoon, had helped build James Cameron’s submarine, which reached the deepest part of the ocean in 2012. Their goal was to make the ROV adjustable so the engineers could adapt it to almost any scientific need. They started pulling designs together in the summer of 2015 and dove SuBastian for the first time in the test tank in April 2016—meeting the year deadline with a month or two to spare.

“I would like to see this be the beginning of how people think about these vessels,” says Schmidt. “That’s always true when you start down a technology path—you are opening possibilities.”

Some of the designs on the multimillion-dollar deep-water robot made the team a bit anxious, says Bingham. To protect valuable electronics at crushing depths, the team created two stout titanium housings that hold surface air pressure. “They are just one human hair away from filling up with water,” says Bingham. “When you have over 6,000 pounds per square inch acting on it—that’s like a car on every square inch!—the ocean just wants to be inside.”

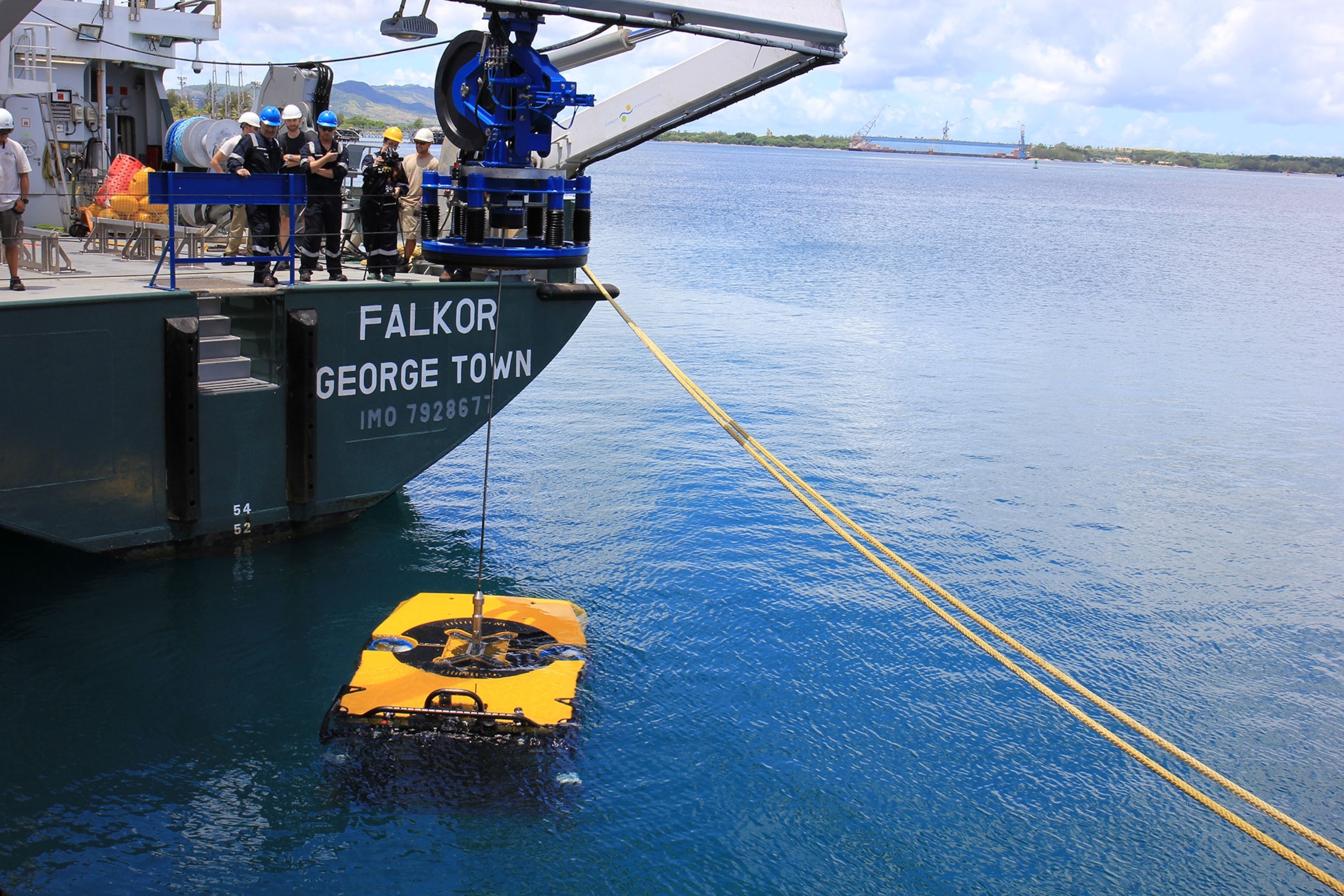

While SuBastian is underwater, it remains tethered to SOI’s research vessel Falkor (both the ship and ROV are named for characters in The NeverEnding Story, a favorite book the Schmidts read to their children). “You can think of [SuBastian] as a team of people under the water talking back to our ship,” Schmidt says.

The heart of SuBastian is actually in its eyes. Like other research ROVs already in use, it has multiple cameras, but two of the 10 cameras on SuBastian are the highest resolution cameras available, built by the same engineer who worked on Cameron’s submarine. While SuBastian captures high-resolution images from the seafloor, Falkor’s onboard supercomputer and nearly a petabyte, or a million gigabytes, of data storage gives scientists a rare opportunity to analyze data while still at sea, thus avoiding a costly return trip. Falkor also broadcasts live video online from the ROV, as the research vessels Okeanos Explorer and Nautilus do, so scientists and the public can skip the seasickness and tune in from land. However, on Falkor the entire video of the dive remains available on YouTube for anyone to access later.

Schmidt says the ROV will help SOI focus its research goals, such as studying the deeper parts of our ocean—up to 2.8 miles below the surface. Scientists will be able to use Falkor and SuBastian for free, but winning space onboard is competitive. Researchers have to agree to share their data openly and freely, sometimes even as they're collecting it—an uncommon practice among scientists who are protective of their work. But, says Schmidt, “those who’ve done it are happy they did it, are still publishing, and no one is stealing their data. What people most feared is not happening.”

The ROV and its team recently finished its inaugural field test in Guam. The first science cruise using SuBastian, which will explore hydrothermal vents and search for life in the Marianas back-arc, is slated for December 2016. At that time, the ROV will be loaded with a huge piece of equipment: a hot-fluid sampler nicknamed The Beast.

SuBastian and Falkor are a far cry from Jacques Cousteau’s Calypso, which Schmidt watched on her black-and-white television as a young girl. “Ocean exploration needs to have a platform like space exploration has had, in terms of gathering people’s imaginations about what’s there,” she says.

In that regard, SuBastian will bring the ocean’s otherworldly marvels closer to the surface.