From Whales to Buoys: Finding a New Sport in an Old Custom

These historic and decommissioned whaleboats are connecting young Azorean racers to their powerful past.

In 1987, the whaleboat Maria Armanda took to the sea for one last hunt. Though whaling had officially ended in the Azores several years prior, the men whose livelihoods had depended on it could not let it go easily. Fast forward 20-some years, and the man who captained this last hunt stands in the harbor, watching his old boat cross the finish line in a whaleboat regatta, with a man more than 60 years his junior now in charge.

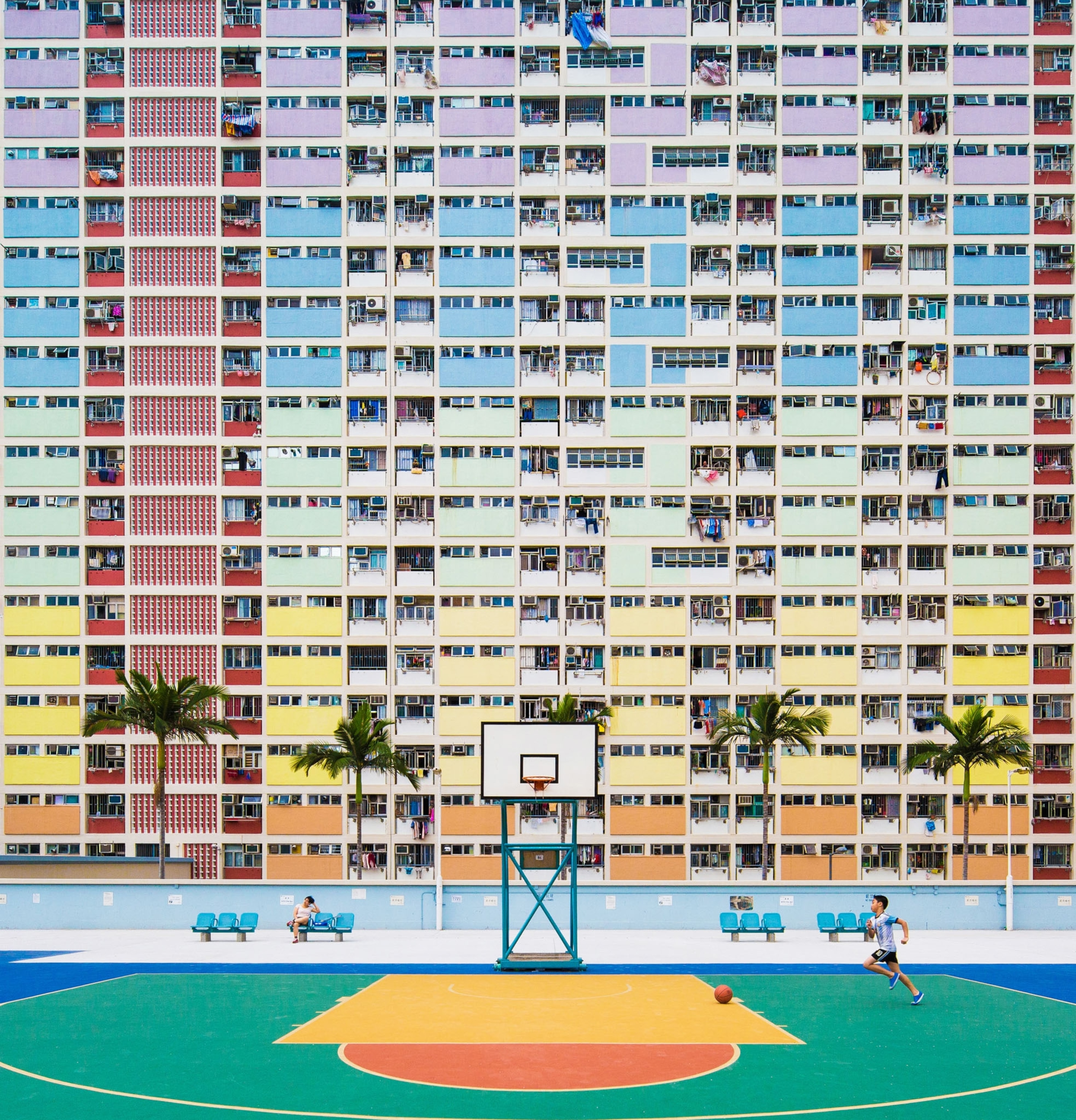

Azorean whaleboats are a vessel of particular beauty. Just shy of 40 feet long, the handcrafted and colorful wooden boats take to the water with an ease and silence that make you feel as though you are floating just on top of the sea. First built in the late 1800s, the seven-man canoes were adapted from the American whaleboats many Azorean men had come to know well during the height of American whaling, when they were taken on as crew.

Throughout the years, while the rest of the whaling world took to factory ships and grenade harpoons, Azoreans continued catching only small numbers of sperm whales with hand harpoons out of these traditional boats.

Teaching an Old Boat New Tricks

No longer used for whaling, the boats are now an icon of Azorean culture and the centerpiece of a vibrant sports culture among younger generations, who use them for rowing and sailing.

Every summer, the whaleboats come out of storage and the islands come alive in anticipation of the regattas. Teams practice every day after work, race on Saturdays, and rest on Sundays before starting it all over again. The transition from hunting for necessity to adventuring for sport happened quickly—and effectively.

We removed the whale, and the interest has not vanished.Filipe Fernandes, Maria Armanda Captain

“What we did with the whaleboats, which is absolutely incredible,” says Filipe Fernandes, current captain of the Maria Armanda, “is we removed the whale. And the interest has not vanished. People still relate to the whaling because old rivalries are still present today, old stories from whaling still come up in discussion nowadays when things heat up over competition. But when you look at other areas, you see how impressive that is, because I can’t imagine in bull fighting that they would find a way to remove the bull and still keep the emotion and the attraction around the activity. I think we have a lot to be proud of.”

Connecting to a Storied History

For those with whalers in the family, crewing the boats offers a particularly personal connection to their heritage and their family. Simone Silva, age 22, describes a teammate: “In my boat, I have one girl whose grandfather died four years ago. He was one of the last whalers, so rowing for her is keeping the tradition, keeping the memory of her grandfather alive. So all of us have different ways to connect to the boats and to rowing.”

Luís Bicudo, a local filmmaker who produced a film about the whalers several years ago, is the grandson of whaler himself. When he started rowing and sailing the whaleboats, his connection to his family and his work only became stronger. He describes, “It was really important [to sail] to understand how things were made, how they were handled in the boat, and to ask questions. Every time I sailed in the whaleboats or raced in a regatta I came back to talk to my grandfather. I used to debrief with him, what happened, what boat I was in, who won—and he liked to hear that. And he also gave me some feedback.”

For Fernandes, the history is personal in a different way. “My first memory of a whaleboat was going down to the Nautical Club in Lajes to go swimming,” he says. “And on the ramp, oddly enough, was Maria Armanda—my boat today. And it caught my attention because the name of the boat is the name of my two grandmothers. It would have been impossible to imagine at the time that I would be the official of that boat.”

Several years ago, he found a document for the sale of Maria Armanda to a whaling society in Lajes. It was dated over 100 years ago. Fernandes’ connection to his heritage is deepened through this particular boat, which is the only one in the Lajes do Pico fleet that retains some of its original materials. “Even if it only has a few ribs, there is something there from the original boat, so some of the wood that is under my feet somewhere caught whales. When you’re on a stage where some incredible things happened, you have to feel a lot of respect for that.”

A thing that we now do for fun they [did] for necessity.Carla Nunes, Whaleboat Racer

Even for those who weren’t expecting it, racing the boats has brought them closer to their history. “It wasn’t initially about the culture,” says Andre Fernandes, a rower on his brother Filipe’s team, “It was about the sport. But then the sport brought me the need to know about the culture that I was living. We live very differently from how [the whalers] lived. But I feel—I think we all feel—responsibility on a boat that has a long history that went whaling. So I think it’s a little bit special for most of the people that go on these boats for competition.”

Carla Nunes, a transplant from mainland Portugal, was not even aware of whaling history until she started sailing whaleboats. The more she learned, the more she was amazed. “The times when I go out it’s for fun. Sometimes we get regattas with bad weather and strong winds and it’s rough. But then I saw the pictures and the movies and when [the whalers] went out, it was rough. They went out to have money to feed their families. I know now that it’s really physically demanding, so it’s like, wow, the respect for those people that went out, risked their lives to catch a whale, to be able to feed their families. A thing that we now do for fun they [did] for necessity.”

From Whaling to Regattas

Although most regattas today separate rowing and sailing, one of the races held during Semana dos Baleeiros (Whaler’s Week) in Lajes do Pico combines the two, just as whalers would have had to do. Starting from a run, the team must carry the whaleboat from the ramp into the water as fast as they can with everything they need in the boat. They row to the first buoy, sail to the second, and can do either for the homestretch. Several times in the past years, some of the teams have even dressed in clothing like the whalers would have worn. But even with six near-20-foot oars, a more than 28-foot mast, and two sails on board, the boats carry considerably less gear than whalers would have needed—and the end game is a buoy, not a whale.

Such differences can appear to some whalers today as though the younger generation doesn’t know what they’re doing, but today’s competitors want critics to keep in mind that, with different goals, different skills are needed—and that sometimes a change of practice is a conscious act, not a lack of knowledge.

Rowers now take the oars for mere minutes instead of hours, and without the worry of a harpoon line tangling in the rudder, the rudder can stay down and there’s no need for a stern oar. Sail area has increased.

And although it is likely that some traditional knowledge is being lost, Fernandes believes that, ultimately, the skills are being refined and specialized as more information becomes available about rowing and sailing in general. That doesn’t mean that captains like himself don’t listen or incorporate advice from those who knew the boats first though. Speaking of a conversation with Francisco “Barbeiro” Machado—one of the most experienced and respected whaleboat captains during the whaling days in Lajes, Fernandes states: “He asked me out of the blue ‘What do you do in heavy winds when a gust comes and you can’t hold the boat?’ After hearing Fernandes’ answer, Barbeiro suggested, ‘Try easing the jib. Ease the jib. You’ll see it works and the boat will come up immediately, try that.’” It was their last visit before Barbeiro passed away.

Carrying the Torch

The passing of iconic whaling figures like Barbeiro is a reminder that in the next decade all or nearly all those who intimately know the boats’ original purpose will be gone. Looking to the future, it is important to everyone adventuring for sport in the whaleboats that this tradition continues.

At the moment, fewer teenagers are flocking to the whaleboats than before. In Lajes, teams have never actively recruited, but they may have to start if the current trend continues. That doesn’t mean people see this tradition ending though. Silva, who has been racing since she was 12 years old, believes in the dedication of people who participate in the whaleboat regattas today. She says, “Now [community] is [important] because we don’t hunt, so we’re keeping the tradition alive, sharing stories, and keeping connected with people from the other islands. We can then teach others to row and sail and to share our stories.” Nunes, speaking about the children of the women on her team, states, “These babies are practically born in the whaleboat. [The women] usually bring them to training and they sit near their mothers looking at us like ‘Wowww.’ Then they become more verbal and say ‘Row! Row!’” Of one young four-year-old, Luana, Nunes explains, “You see she will be a women’s skipper someday. The bug is there.”

Even after the last living former whaler passes away, Bicudo thinks whaling heritage will stay alive—as long as people are using the boats. He says, “It is always a relation to the past because we are using the whaleboats. And I think that’s the most important thing about this. Because if we put it in perspective, how many things of our heritage are gone? So putting it in that perspective, I’m really proud we have the whaleboats and that they’re being used and not just in a museum.”

Gemina Garland-Lewis is a photographer, EcoHealth researcher, and National Geographic Explorer based in Seattle, Washington. Follow her on Instagram @geminarose.