Rhino Hunt Permit Auction Sets Off Conservation Debate

Dallas Safari Club hopes to raise money for conservation, but critics pounce.

A group called the Dallas Safari Club is auctioning off the chance for one hunter to shoot an endangered black rhinoceros in Namibia. The club claims all proceeds will support conservation of the embattled species, but the the announcement has touched off a firestorm of criticism around the world.

Ben Carter, executive director of the Dallas Safari Club, told the media that 100 percent of the auction proceeds will support the Conservation Trust Fund for Namibia's Black Rhino.

"There is a biological reason for this hunt, and it's based on a fundamental premise of modern wildlife management: Populations matter; individuals don't,” Carter said. “By removing counterproductive individuals from a herd, rhino populations can actually grow."

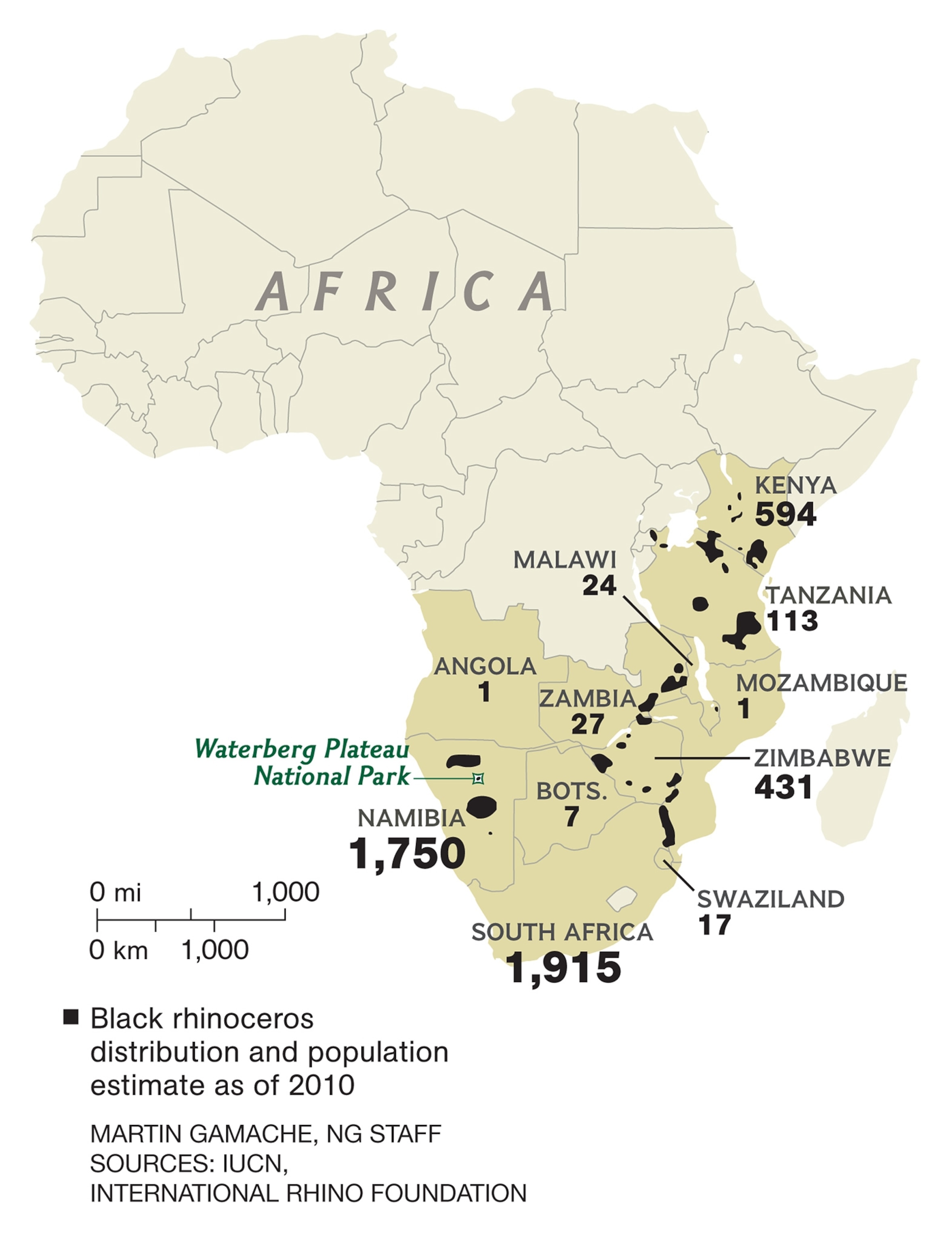

Scientists estimate that there are about 5,055 black rhinoceroses left in the world, a decline of about 96 percent over the past century or so. They were listed in Appendix I of CITES in 1977 and on the U.S. Endangered Species Act in 1980; they are are currently listed as critically endangered on the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species.

Even so, all three of those bodies—CITES (Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora), the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, and IUCN—are on record as allowing limited, targeted hunting.

In particular, CITES has granted Namibia an annual export quota of up to five hunter-taken black rhinos. Scientists estimate there are 1,795 of the animals living in the African country.

As in other rhino countries, in Namibia the animals continue to be menaced by illegal poachers and habitat loss. Rhino poaching has hit an all-time high, with two to three rhinos killed by poachers every day across Africa, largely to feed demand for their horns in China and Vietnam. The keratin-based horns, which are made out of the same material as human fingernails, are marketed as medicines there for everything from cancer to hangovers. (See “Rhino Wars” in National Geographic magazine.)

The Dallas Safari Club (DSC) says it expects the permit to sell for at least $250,000, possibly up to $1 million. According to an official release from the club, Namibia has never before sold a black rhino-hunting permit directly outside of its borders.

Typically, the five Namibian permits that are issued each year are sold to local hunt operators, which then book clients from around the world. Those permits have typically gone for a few hundred thousand dollars.

In recent years, however, Americans have not been able to import black rhino trophies into the U.S., which has limited the interest from that country, reported the DSC. But the Fish and Wildlife Service is set to grant an exemption in this case, as part of a deal that Namibians will hope will also bring in a higher price for the permit, explained Nelson Freeman, a spokesperson for Safari Club International.

The move is not without precedent. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service had previously granted a permit for a trophy of an older, nonbreeding male black rhino taken from Waterberg Plateau National Park in Namibia in 2009.

“This hunt removed an animal that was counterproductive to herd growth and generated $175,000 for rhino conservation efforts,” according to DSC’s press release.

Conservation Outrage

News of the permit has attracted some public support, especially from hunting groups.

“Though it may seem counterintuitive to critics, the hunt is being sanctioned by scientists around the world as helpful to the future of a rare species,” according to the DSC.

The club said that the hunt would target an older, postbreeding male black rhino (a bull), an animal with a reputation for being territorial and for even occasionally charging and killing younger bulls, cows, or calves.

“Removing these individuals can lead to greater survival of other rhinos and, in turn, greater abundance of the species,” wrote the club.

But Jeff Flocken, North American director for the International Fund for Animal Welfare, takes exception with the proposed auction for a black rhino hunting permit.

“Killing animals to save them is not only counterintuitive but ludicrous,” he told National Geographic. “We're talking a highly endangered species, and generating a furor to kill them in the name of conservation is not going to do anything to help them in the long run.” (See “Opinion: Why Are We Still Hunting Lions?”)

Flocken said the problem is that hunting sends a signal to world markets that the animal is worth more dead than alive.

“The value of photographic and wildlife-viewing safaris far outweighs the value of trophy hunting,” he said. “When they kill a black rhino, that is one less incentive for someone who would come take a picture, and come again and again.”

Flocken said killing a rhino permanently takes the value of that creature out of the country, with economic consequences. “Everyone wants to see a rhino when they go to Africa, but not everyone wants to go and shoot one.”

“The rarer an animal becomes, the more incentive there is to kill one” he said, noting that the same trend is at work with exotic animal products like polar bear rugs and elephant ivory. Prices keep rising as populations fall, despite international restrictions on trade in endangered animals.

The Humane Society of the United States is petitioning the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to prohibit the auction winner from bringing the black rhino trophy into the country.

"I think if they were multimillionaires and they were serious about helping rhinos, they could give money to help rhinos and not shoot one along the way," the group’s president, Wayne Pacelle, told UPI. "The first rule of protecting a rare species is to limit the human [related] killing."

Wider Issues in Rhino Conservation

The debate over the Namibia hunt is a microcosm of broader wildlife issues in conservation across Africa. Other countries in the region have been grappling with whether to allow such limited hunting.

In a recent post on National Geographic’s website, Dereck Joubert, a conservation filmmaker and National Geographic Explorer-in-Residence, celebrated the end of all legal hunting of endangered wildlife in Botswana, which was announced in September.

“Today, safari hunting ends!!” Joubert wrote. “The end of an era of conservation by the gun, and the beginning of a new era for Africa, a more gentle caring one. My congratulations to the government of Botswana, with deep gratitude from me, from all concerned citizens, and from the informed global community of people that are concerned about wildlife.”

Several other countries continue to allow the practice, and the British conservation charity Save the Rhino argues that the debate around limited hunting should be nuanced.

“Let’s see if MET [Namibia’s Ministry of Environment and Tourism] has made the right call on holding this auction in Dallas,” the group said in a statement.

Save the Rhino argues that it makes sense for Namibia to try to earn more money for conservation by taking the auction out of its backyard and into the wider world—specifically a world with well-heeled hunters, like Dallas.

“Couldn’t they get $750,000 without having to suffer an animal being shot? Well, yes,” Save the Rhino said in a statement. “It would be nice if donors gave enough money to cover the spiralling costs of protecting rhinos from poachers. Or if enough photographic tourists visited parks and reserves to cover all the costs of community outreach and education programmes. But that just doesn’t happen.”

Melissa Simpson, director of science-based conservation for the Safari Club International Foundation, argued similar points in a recent opinion piece for National Geographic’s website.

“As with the regulated hunters in the United States, the regulated hunters in Africa make a vital contribution to conservation efforts, primarily through the revenues their hunting expeditions generate for local communities and wildlife resource agencies,” she wrote.

In 2009, WWF sent a letter to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service in support of limited, managed hunting of black rhinos in Namibia.

“WWF believes that sport hunting of Namibia’s black rhino population will strongly contribute to the enhancement of the survival of the species,” the group wrote, citing the generation of income for conservation and the removal of postbreeding males.

Social Response

The auction has set off something of a global debate.

Stephen Colbert took aim at the planned auction with his signature satire. “The Dallas Safari Club says they will save the black rhino by auctioning off the chance to shoot one. It’s like the old saying: If you love something set it free; then when it has a bit of a head start, open fire,” he said on air last week.

On the website Ecorazzi, which covers environmental issues with a pop culture twist, a reader wrote, “Ah, Texas! We Americans can be so proud! Hunters are not conservationists. Totally bizarre. Thank you for your good work!”