Killer Fungus That's Devastating Bats May Have Met Its Match

A bacterium known to slow fruit ripening shows promise at slowing down white-nose syndrome—a disease that's wiping out bats.

White-nose syndrome has claimed millions of bats since the disease was first detected in New York state in 2006. The culprit—a fungus—eats its way into the wings of its victims, draining the life out of them. It has shown little sign of stopping in its westward trek across the United States and Canada, but a new treatment could change that.

The treatment is based on a bacterium that inhibits fungal growth, and was originally studied to see if it could slow the ripening of fruits and vegetables. Researchers are in their second year of trials with little brown bats and Northern long-eared bats, and the results look promising, says Sybill Amelon, a wildlife biologist specializing in bats with the U.S. Forest Service in Columbia, Missouri.

Amelon and her team released about 15 treated bats back into the wild on May 19. The treatment helps all but the most heavily infected bats.

If they're treated early enough, the bacteria can kill off the fungus before it gains a foothold in the animal. But even bats already showing signs of white-nose syndrome show lower levels of the fungus in their wings after being treated.

The Right Stuff

A cloud of chemicals given off by the bacteria—a strain of Rhodococcus rhodochrous—seems to be the key to killing or slowing the deadly fungus, Amelon says.

Chris Cornelison, an applied microbiologist at Georgia State University in Atlanta, first tested the bacterium against the white-nose fungus in 2011.

A former colleague had discovered that the bacterium reduced the amount of mold that formed on bananas and surmised that R. rhodochrous was an antifungal, he explains.

"I thought if Rhodococcus can prevent molds from growing on bananas, it may be able to stop a mold growing on a bat," says Cornelison.

The new treatment could be deployed in an entire cave of hibernating bats without having to handle them or leave chemicals in their environment. But Cornelison and colleagues haven't quite figured out how they could deliver the treatment.

The team will also need to figure out their production problem. Cornelison is currently growing R. rhodochrous using special food to get the desired effect on the fungus and can only produce a limited amount.

But if further study proves the treatment is safe for the bats and doesn't have any unintended consequences—like harming other organisms—then the team at Georgia State will have to find a way to ramp up production, says Amelon.

Hands-off Approach

This technique is the latest in a string of strategies developed to deal with white-nose syndrome.

Recent research has shown that the fungus starts to stress a hibernating bat long before the animal shows outward signs of the disease. And the only way researchers were able to confirm the presence of white-nose syndrome in an area was to sacrifice bats suspected of infection. (Find out how this killer fungus burns up bats from the inside.)

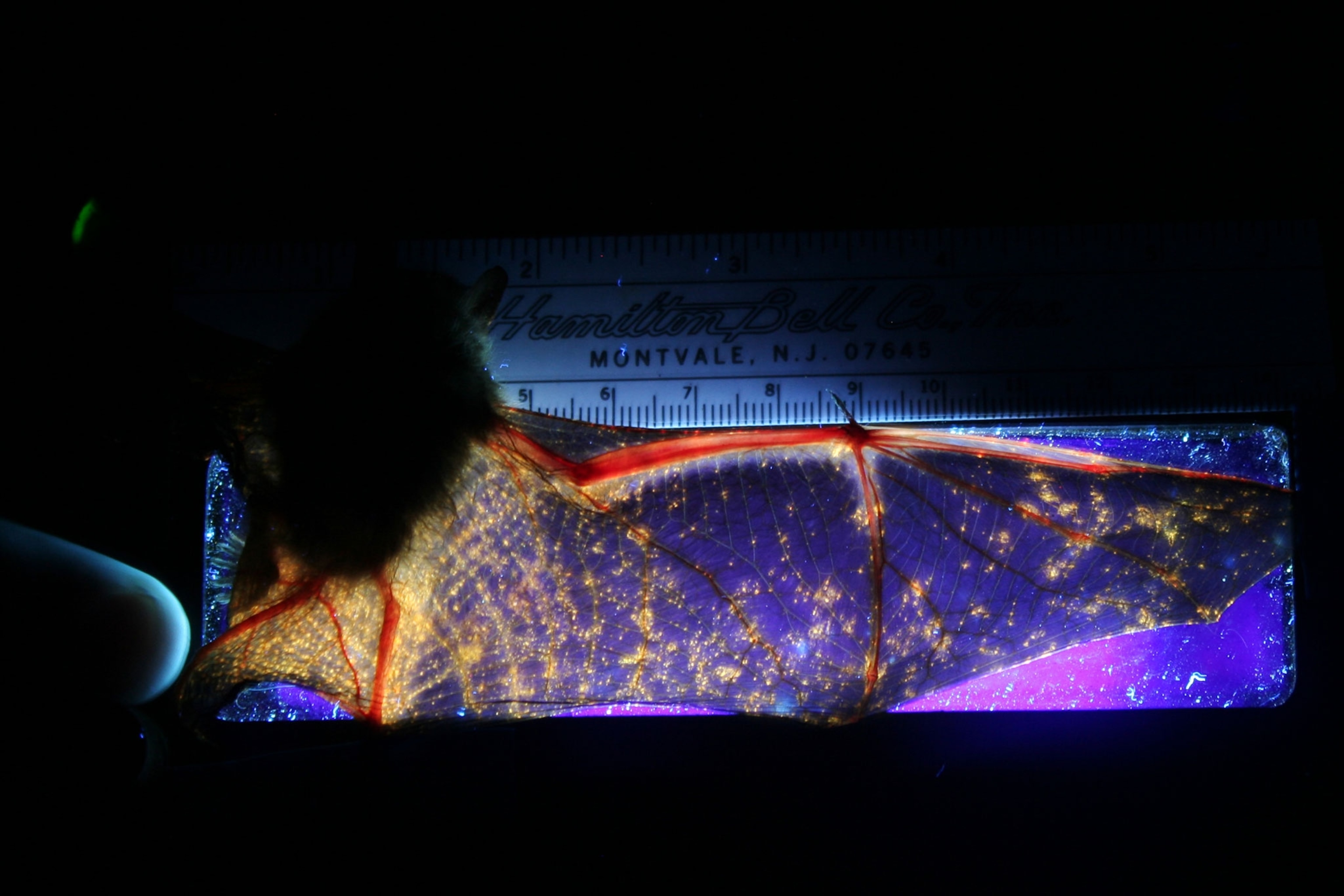

The fungus actually digests live wing membrane, says Greg Turner, state mammologist for the Pennsylvania Game Commission. To test for the disease, researchers had to take sections of a bat wing, stain it for the presence of the fungus, and then look at it under a microscope.

This is changing though, he says. Turner and colleagues have developed a way to spot damaged sections of a bat's wing using ultraviolet (UV) light, and without having to kill the animal.

Under UV light, affected areas of a bat's wing glow a fluorescent orange. Researchers can hone in on those suspect sections using a small biopsy—about 0.1 inches (three millimeters)—rather than the whole animal, Turner explains.

Colleagues in Europe were able to use the UV light technique to check 15 different bat species, Turner says. They found that 11 were infected, 10 of which they hadn't known about prior to their survey.

Turner says that the UV light technique would probably be most effective as white-nose syndrome marches into new territory. As a monitoring tool, it's effective and doesn't harm the animals, he says.

The U.S. Forest Service's Amelon adds that her treatment will also likely be most effective on the front lines of this disease as a preventative rather than a cure. Bats living in areas that have already been hit hard by white-nose syndrome seem to be adapting to living with the disease.

Bats in Pennsylvania are putting on a lot more weight before heading into hibernation, Turner says. The tubbier bats seem better able to deal with the energy drain the fungus puts on their body.

"Since [the treatment] seems to be most effective in prevention rather than as a cure, we think the front is the most important place to deploy it first," Amelon says.

Follow Jane J. Lee on Twitter.