Meet Tatu and Loulis—the last of the 'talking' chimpanzees

In the 1960s and '70s, a group of chimpanzees astonished the world by learning sign language. Only two remain, and one question still lingers: Was it worth it?

Lazing outside her home in the Montréal suburb of Carignan on a breezy day in June, Tatu the chimpanzee notices she has visitors. She slowly ambles over, peers downward at the onlookers, and draws her right index finger across her forehead.

The gesture is American Sign Language (ASL) for the color black. It’s Tatu’s favorite color and the word she uses for describing things she thinks are cool. The chimpanzee, 49 years old at the time, is expressing something akin to, “Oh, company. Neat!”

Next Tatu makes a fist and brings it to her mouth in a circular motion. “Ice cream would be a good idea,” agrees Mary Lee Jensvold, a chimpanzee researcher and associate director of the Fauna Foundation, a nonprofit dedicated to providing sanctuary to nonhuman primates, including Tatu and a 47-year-old male chimpanzee named Loulis.

Tatu and Loulis are the last two surviving chimps from a series of experiments that began in the 1960s. The pair have spent their entire lives in captivity, including stints at facilities in Oklahoma and Washington, where researchers studied their ability to learn ASL—hoping to challenge the prevailing belief that only humans could use language.

Since 2013 they’ve been living at Fauna, where both chimpanzees continue to sign. Tatu, the more loquacious one, has mastery of 215 signs, while Loulis can use 78. Among their favorite things to talk to their caregivers about are food and activities. Tatu is partial to cheese and enjoys a nice cup of coffee or tea, while Loulis prefers asking his caregivers to play a game of chase.

Whether language is unique to humans has been a subject of fascination to linguists and scientists for centuries, and in the 1960s they began turning in earnest to one of our closest genetic relatives to finally put the question to rest. This research was pioneered by a pair of psychology professors at the University of Nevada, Reno, the husband-and-wife couple Allen and Beatrix “Trixie” Gardner, who sought to prove that under the right circumstances chimpanzees could learn a human language.

(Read Jane Goodall’s original tale of chimpanzees, published in 1963.)

Their research began in 1966 with an infant chimp, taken from West Africa for use in U.S. Air Force experiments, whom they adopted and named Washoe. The Gardners raised Washoe as much like a human child as possible. She learned to use a potty (which she would call “dirty good” in sign language), played with dolls, and admired the photos in magazines.

Washoe became a sensation in academia, but her fame would be surpassed in the 1970s by two other primates: Koko the gorilla and Nim Chimpsky. While the methodologies for those experiments would later come under fire, casting into doubt whether Koko and Nim understood what they were saying, the same was not true for Washoe, who ultimately developed a vocabulary of 245 words before her death in 2007 at Central Washington University.

The Gardners repeated their experiments with four more chimpanzees: Moja, who loved to paint; Dar, who enjoyed wearing hats and examining mechanical objects; Pili, a male who died from leukemia before age two; and Tatu. They eventually turned their work over to their former graduate student, Roger Fouts, and his wife, Deborah, who took in Washoe, Moja, Dar, and Tatu, as well as young Loulis, who became the first and only chimp to learn ASL from other chimps.

It’s unlikely that Tatu and Loulis are aware they were at the heart of groundbreaking scientific research, or the complex ethical questions that came with it. While the chimpanzee ASL experiments taught researchers much about how humans evolved our communication abilities, the knowledge came at a cost to the research subjects. Now in their geriatric years (chimps rarely live past 60), Tatu and Loulis will likely never again see their natural habitats in the tropical forests of West and Central Africa. Successfully introducing chimps raised in captivity to the wild is impossible. Not only do they lack the skills to survive in the wild, but they could possibly face a violent rejection from any communities of chimps they meet. Barring a transfer to another similar haven, they are almost certain to live out the rest of their days at Fauna.

That cost would eventually lead some of the same scientists who raised the chimps to develop intense moral qualms about their most famous work—and even turn against it.

How to teach sign language to a chimpanzee

To psychologists in the behaviorist school, which arose in the early 1900s, animal behavior was merely a response to external stimuli. They believed that other species’ inability to talk wasn’t just evidence they lacked the proper anatomical structures; it made studying their inner life, a concept the school found largely inaccessible, impossible. For some, it was even evidence of a lack of true consciousness. Linguists, including Noam Chomsky, pushed the belief that humans alone had an ingrained natural grammar, from which all languages emerged. As the thinking went, animals would have no use for language.

The Gardners, however, believed that chimps would have plenty to say if given the proper tools to do so.

They weren’t the first to suspect chimps were capable of communication. In the 1930s another pair of married scientists took a chimpanzee named Gua into their home to see what would happen if they raised Gua in the same manner as a human child. That included teaching Gua English while they raised him alongside their human son, Donald. As documented in their book The Ape and the Child, Winthrop and Luella Kellogg found that the chimp was actually faster at learning to use a spoon and open a door, as well as responding to spoken commands. However, they abandoned the experiment after Donald began speaking and Gua did not. Further experiments conducted beginning in the 1940s showed that chimps lacked the necessary anatomical structures to speak English—though one chimp, named Viki, was ultimately able to say mama, papa, and cup after intensive speech therapy that involved humans manually shaping her mouth to make the right sounds.

With human vocalizations out, the Gardners theorized that apes would be able to learn ASL much like the way they learn to communicate via gestures in the wild. They’d have to be fully immersed, surrounded by human caregivers who would communicate with them and each other solely in ASL.

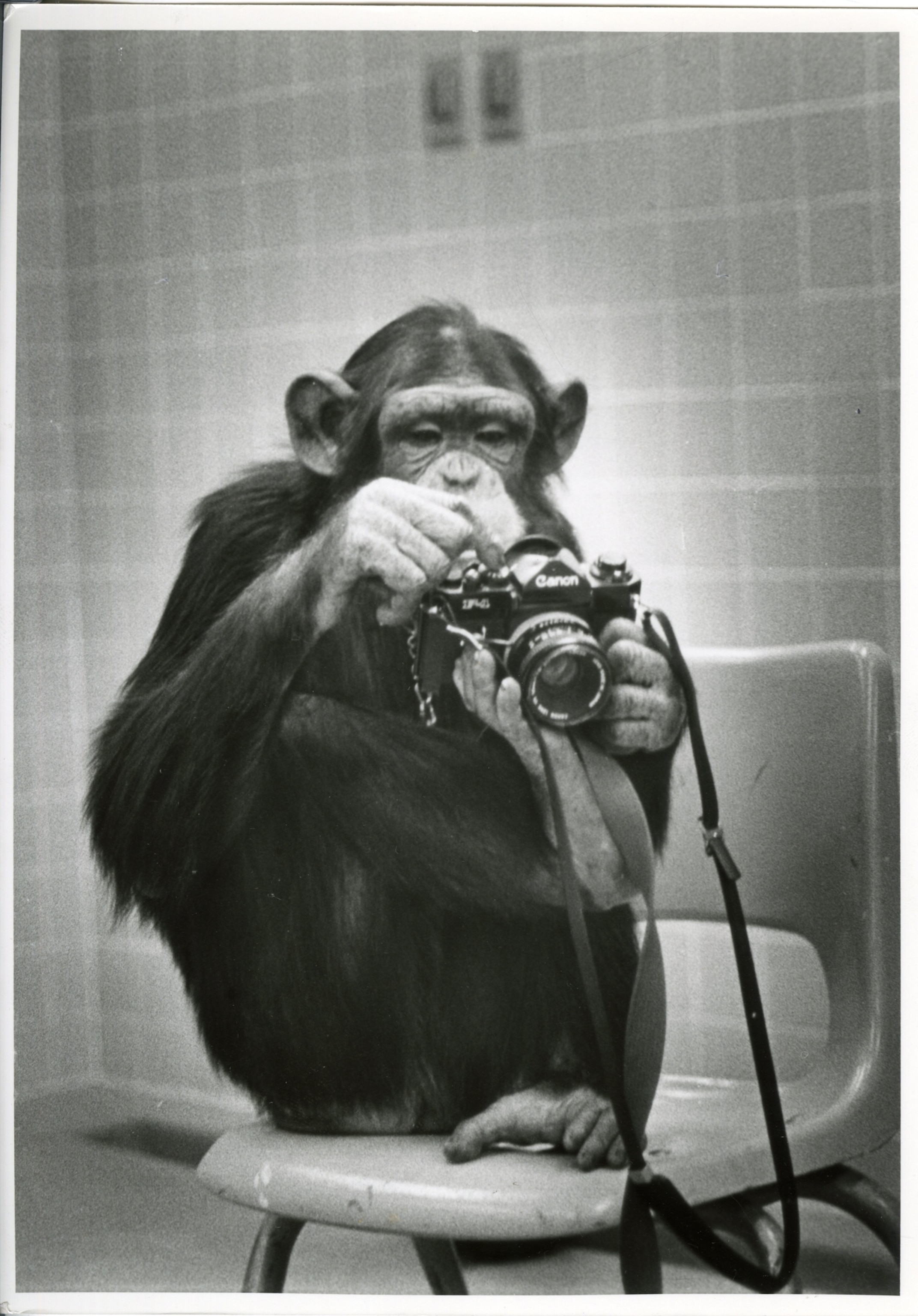

In 1966 the pair put their theory into practice. Over the next 15 years, the Gardners and their team of caregivers played with, fed, chased, and tickled their young, hairy charges: Washoe, Dar, Pili, Tatu, and Moja. Eventually, each of the chimps began signing back. As a toddler, Washoe quickly grasped the sign for “more” and soon added the gestures for things like “bird,” “smoke,” and “flower.”

(Chimps consume the equivalent of more than two alcoholic drinks a day.)

Their work inspired others to try and replicate their results, including a Columbia University professor named Herbert Terrace. In 1973 he acquired a chimpanzee that he named Nim Chimpsky, in reference to Chomsky. Terrace boasted Nim would soon be able to share his feelings, describe his imagination, and discuss the past and future. These claims, along with the Gardners’ and Fouts’ reluctance to put Washoe in the limelight, led to Nim outpacing Washoe in fame, even appearing on the cover of a 1975 issue of New York magazine.

Terrace would at first claim success, as Nim learned to make the gestures associated with the signs for “banana,” “hug,” and “play.” But Terrace would later conclude that the chimp had been reacting to prompts from his trainers, making the gestures to earn rewards, with no actual understanding of what he was doing. Nim, he believed, could not use the signs he learned conversationally or string them together into sentences that reflected thoughts.

Perhaps the problem wasn’t with Nim but with his environment.

“Nim lived with a family in New York on the Upper West Side, but he was brought to a classroom on the daily,” where he was drilled on signs for hours, says Valerie Chalcraft, a psychologist who works as an animal behaviorist and studied under the Gardners in the 1990s. Nim’s lessons were given in spare rooms, lacking the normal stimuli that a child enjoys in their first years. As a result, as Chalcraft puts it, it shouldn’t be surprising that Nim didn’t have much to say. “Human adults don’t teach their kids how to speak with rewards and punishments. It happens in a natural, relaxed setting, an enriched setting,” she says.

Nim also lacked stability and consistency. At least one close caregiver was abruptly cut out of the project, several others left on their own, and Nim had no other chimpanzees around during this era. After Terrace concluded the study in 1977, Nim was transferred to a research facility and then to a biomedical lab. Eventually, he was bought by a philanthropist and lived on a ranch until he died in 2000 of a heart attack at age 26.

In contrast to Nim, the chimps raised by the Gardners enjoyed a more playful environment, closer to that of a human toddler. Take Tatu’s early life, for instance: Born in captivity in 1975 and adopted by the Gardners that same year, Tatu liked sleeping in late and was a stickler for schedules. She had a playful side, developing a love for putting on masks. That glee could sometimes turn a shade impish. Patrick Drumm, a research assistant at the time and now a visiting research scholar at the University of Akron, recalls one incident where Tatu realized Moja was terrified of metal ice cube tray dividers.

“She began chasing Moja around with them,” he recalls. “And then, because it frightened Moja, she tried it on the human companions. It didn’t work so well.”

She and the Gardners’ other chimps proved talkative from a young age. In a series of papers, the Gardners described how the method by which chimps learned sign mirrored how young children learned language, in that they were able to reliably answer simple, direct questions like “Whose that?” and “What you want?”

“Man’s egocentric view that he is distinctively unique from all other forms of animal life is being jarred to the core,” wrote researchers Duane Rumbaugh and Sue Savage-Rumbaugh, who conducted their own linguistic work with bonobos, in a 1978 paper on chimpanzee language research.

But it soon became evident that the Gardners’ ad hoc backyard facility could no longer house increasingly strong chimpanzees. By 1980 the Gardners had sent half of the chimps in their care to the University of Oklahoma, where they were looked after by Roger Fouts, the Gardners’ former graduate student. Tatu and Dar would be the last to end up under his care in 1981.

Fouts would go on to make a new series of discoveries into chimpanzee communication. He would also begin to question the morality of his own life’s work.

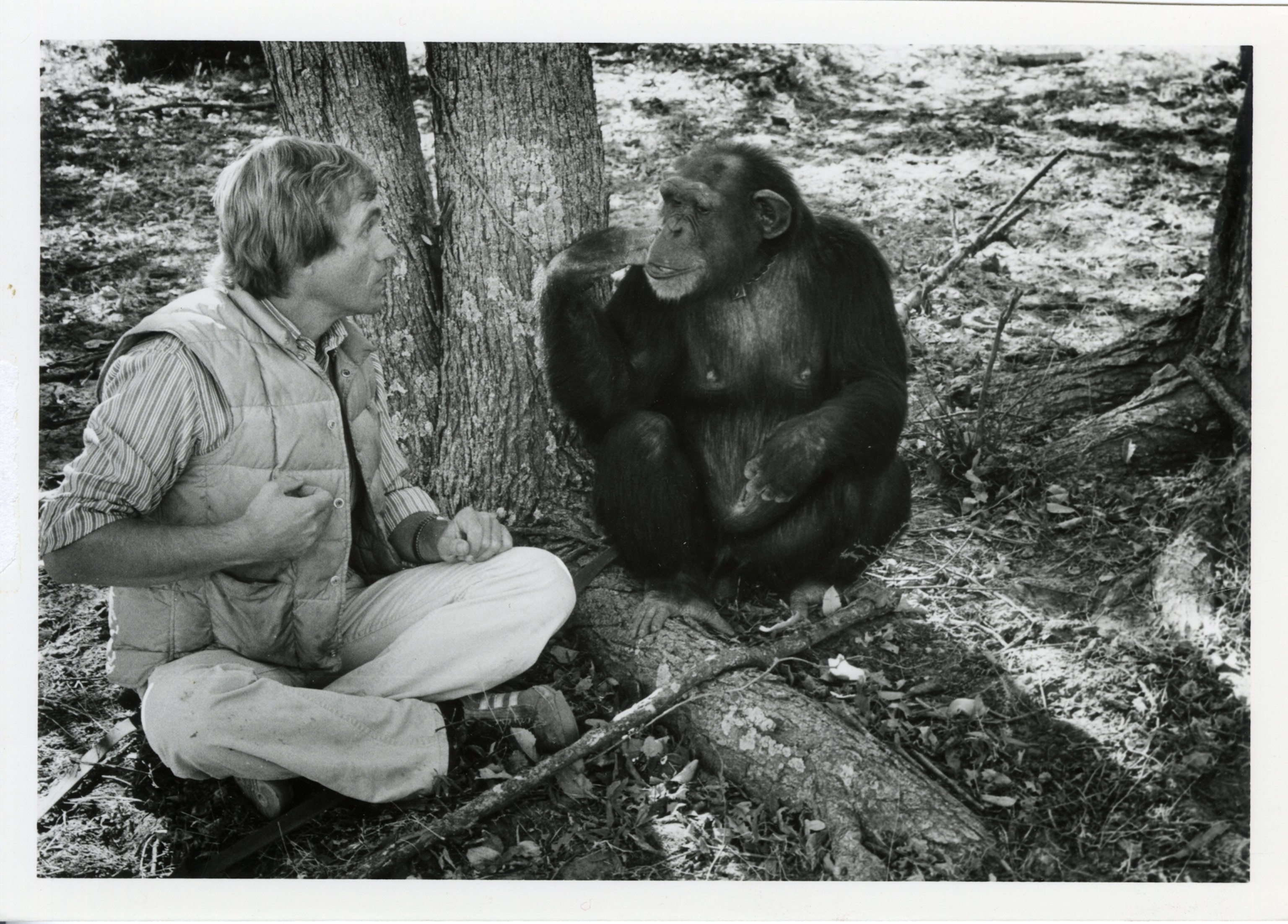

An astonishing discovery—and the regrets that ensued

Fouts had stumbled into primate ASL research almost by accident. Originally aiming to specialize in child psychology but recently married and with a child on the way, he found himself desperately searching for a graduate assistantship to get his out-of-state tuition waived at the University of Nevada. Just as he was about to give up, he was referred to the Gardners. At his first meeting with the young Washoe, the chimpanzee leaped into his arms for a hug. The assistantship was his.

His studies were wrapping up just as the Gardners realized Washoe was growing beyond their ability to care for her. When they decided to send her to the University of Oklahoma’s primate studies facility, Allen Gardner pushed Fouts to go with her as a caregiver and continue his research with her while there. Fouts and his wife Debbi, who would become an integral part of his work, agreed.

While in Oklahoma, Washoe experienced a tragedy that would ultimately bring another chimp into their orbit—one whose ability to learn would astound the scientific community.

In 1979 Washoe gave birth to a baby named Sequoyah. The baby was born weak and would only grow weaker after a bout of pneumonia, to which it succumbed after just a few months of life. According to Fouts’s 1997 memoir, Next of Kin, Washoe grew despondent, refusing to eat. In a bid to save her, Fouts acquired a baby chimp from Emory University’s primate research center: Loulis.

In his memoir, Fouts recalled the moment when he gave Washoe the news of the new baby chimp’s arrival. “For the first time in two weeks, Washoe snapped out of her trance and became excited. BABY, MY BABY, BABY, BABY! she kept signing as she hooted for joy and swaggered on two legs. Her hair was standing on end.”

(Studies show chimpanzee moms are more like us than we thought.)

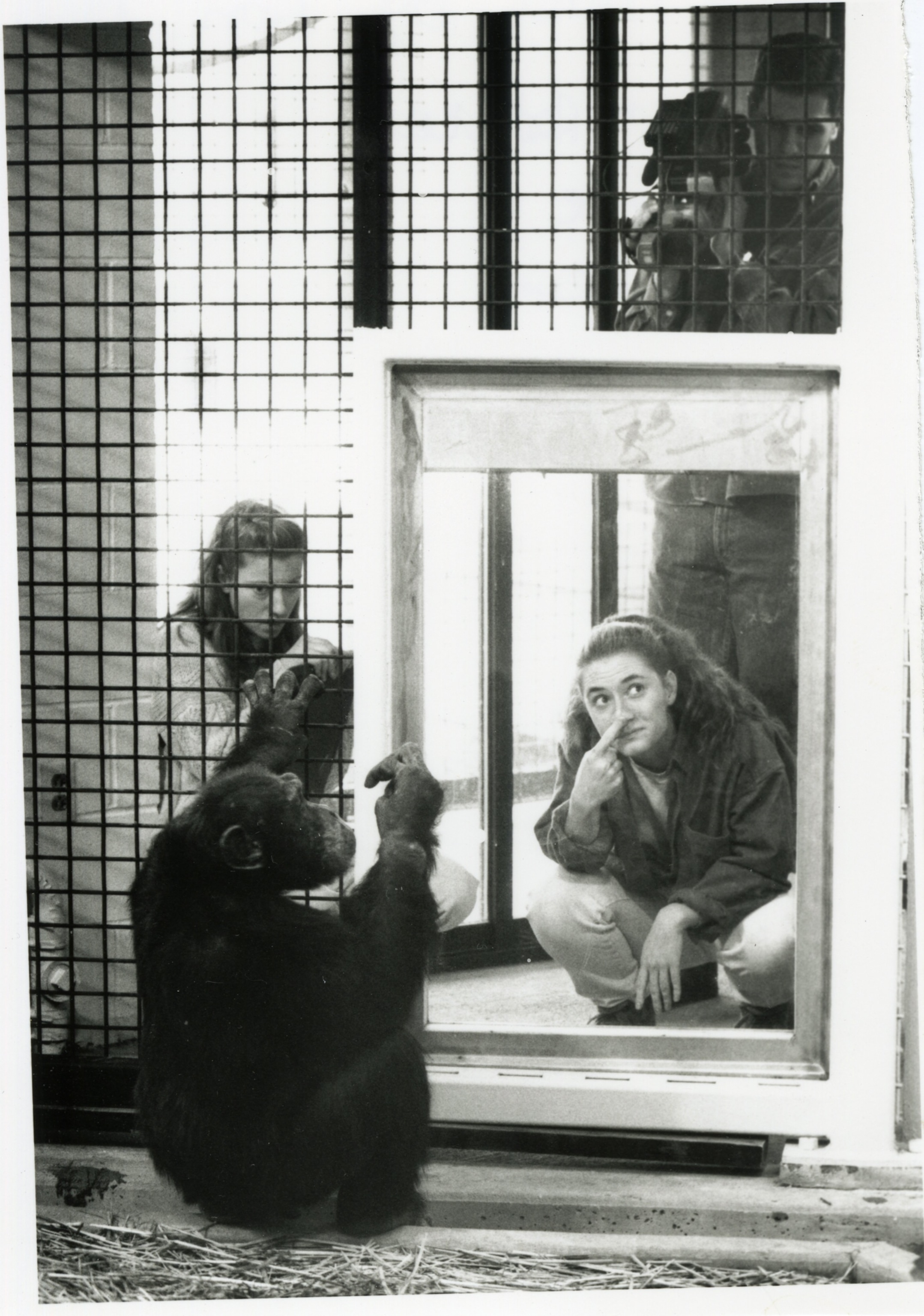

The arrival of Loulis marked a new phase in the research: Could a chimpanzee learn sign language from other chimps? To test the theory, Fouts and his team refrained from signing around Loulis.

As Loulis began adjusting to his new life, he soon began imitating his surrogate mother’s signs. First he began to sign “come” or “gimme.” Later he began to ask for hugs, drinks, or tickles, all signs he picked up from Washoe. Eventually, he began signing short phrases, such as “hurry gimme.” The learning wasn’t just passive: Sometimes, Washoe would take Loulis’s hand and mold it into an appropriate sign, just as humans had done for her when she was an infant.

That a chimpanzee could teach a human language to another chimpanzee was nothing less than astonishing. In the years since, field research has revealed that chimp mothers teach many skills, such as using tools to lure tasty insects, to their offspring.

Yet, despite these successes, Fouts grew to have deep reservations about his work. In March 1987 he and Jane Goodall visited a biomedical facility where HIV research on chimps was being conducted. The pair saw dozens of chimps, including infants, living in small, dark, isolated cages. Some chimpanzees rocked back and forth, a clear sign of intense negative emotions. At least one chimp just clung to the bottom of its cage. After a career spent developing loving, affectionate relationships with chimpanzees, Fouts was horrified by what he witnessed. While his work was conducted in more comfortable living conditions, he became convinced it was just a lesser wrong than other injustices committed in the name of science.

“When we began locking chimpanzees away, we didn’t know any better, but today we do,” he wrote in his memoir. “We know that chimpanzees are not mindless beasts but highly intelligent and inventive beings who have been transmitting complex cultures for millions of years. They are our evolutionary brothers and sisters. What are the moral implications of this scientific revelation?”

(How Jane Goodall changed what we know about chimps.)

The proper place for chimps, he came to believe, was in their native habitats. Any laboratory or refuge, no matter how comfortable, was still a prison.

Fouts joined forces with Goodall to campaign for more humane treatment of the animals he had spent a career studying. At one 2002 symposium where the pair spoke, Fouts compared the plight of these animals to how Nazis treated Jews and the mentally disabled.

“We abuse animals to make ourselves feel better, and we justify it,” he said.

The movement caught on. Scientists signed petitions against practices such as infecting chimps with HIV, and animal rights groups organized protests on university campuses and outside labs. “Chimpanzees who survive a laboratory and humans who survive traumas share a common suffering,” said Theodora Capaldo, who headed an effort to ban chimpanzee research in U.S. labs, in a 2008 press release announcing a study finding chimps could suffer from post-traumatic stress disorder. “Yet science imposes a species barrier on compassion.”

These efforts ultimately worked. In 1997 the Air Force, the very entity that had first taken Washoe from Africa decades earlier, announced it would no longer conduct biomedical research on chimps. By 2015 the U.S. National Institutes of Health came around as well, saying it wouldn’t support such research on chimpanzees.

While many chimps that had been used as lab subjects now reside in sanctuaries like Fauna, according to ChimpCARE, 143 chimps remain in research facilities across the United States. Spared from being used for biomedical experimentation, instead they participate in cognitive and behavioral studies. Sixty-nine others, however, are in unaccredited facilities, are being kept by exotic pet breeders, or are being used in the entertainment industry. Another 237 live in accredited zoos.

“Chimpanzees should be left alone to live their lives in their native habitat, and there is no research that can justify their exploitation,” Fouts said in an email to National Geographic. “Using an endangered species to help an overpopulated species become more overpopulated or to answer someone’s scientific question is irrational and immoral.”

How language research is evolving

These days, scientists are still interested in how chimps communicate, but have focused on ways to study them without stealing them away from their homes. Some research focuses on how the evolution of language is related to the organization of the brains of humans and one of our closest genetic relatives. One series of recent experiments compared MRIs of chimpanzee brains that were taken before the NIH ban to MRIs of human brains and found that we share a key highway of axons in our brains, called the arcuate fasciculus. This suggests that a significant neural structure related to language is common to both species, though the strength of that connection is far weaker in the chimps.

Other scientists have taken to the field to further the work pioneered by Goodall, trying to determine how chimps communicate among themselves.

Among the most prolific researchers is Catherine Crockford at the National Centre for Scientific Research based in Lyon, France. After beginning her career as a speech and language therapist in London, focusing on speech and language disorders, she found herself aching to be in the jungle. Having read the cross-fostering studies about Washoe, Tatu, and Loulis, she began wondering if wild chimps would have the same capacity for communication in their own natural way.

Among her findings is that chimp vocalizations have complicated patterns. Though calling it language would be a stretch, there is a complexity to chimp communication. While many animals have calls that signal danger or aggression, Crockford found that chimps combine vocalizations to refer to more specific things, and that the way in which they do so can differ from community to community.

“They have calls that are not only specific to those contexts, but specific to grooming, to nesting, to hunting, to playing,” she says. She concedes that we may find this is true among other animals if scientists put in the time to study them. “But having worked with a couple of other primate species, I don’t think that every animal does. I don’t think baboons do, for example.”

What remains unclear is exactly how these sounds work together. Humans combine sounds, meaningless on their own, into words, and then combine those words into sentences.

“Even though we’re establishing that there is meaning that is conveyed by these calls, it’s still very hard to know how that relates to meaning in humans,” she says.

As one of our closest genetic relatives, chimps were the natural starting point for examining communication outside the human species, but the field hasn’t stopped there. Since Washoe, researchers have turned to examining how many other species communicate with each other in the wild, from baleen whales to titi monkeys. Some scientists have even proposed that with the power of artificial intelligence, it could be possible to decode many of these calls, perhaps even one day allowing humans to literally talk with animals of all kinds.

(How scientists are piecing together a sperm whale "alphabet.")

In light of this movement, it’s not surprising that the tide has turned against the idea that nonhumans lack inner lives. In the past decade, animal rights advocates around the world have campaigned for legal personhood for elephants, bulls, chimpanzees, and more. In 2024 dozens of scientists signed onto a declaration that there is “strong scientific support” indicating animals including vertebrates, cephalopod mollusks, and even insects have a conscious experience.

“When there is a realistic possibility of conscious experience in an animal, it is irresponsible to ignore that possibility in decisions affecting that animal,” they wrote. “We should consider welfare risks and use the evidence to inform our responses to these risks.”

Tatu and Loulis will never go home

As Tatu gazes at her visitors at the Fauna Foundation, Loulis takes notice of the commotion. The younger chimp is less excited about the prospect of company.

Settling next to Tatu, he shakes his head subtly. As associate director Jensvold explains, that’s not ASL; it’s a common chimpanzee behavior indicating swagger. This is his home, he appears to be saying—the strange humans should know their place as guests.

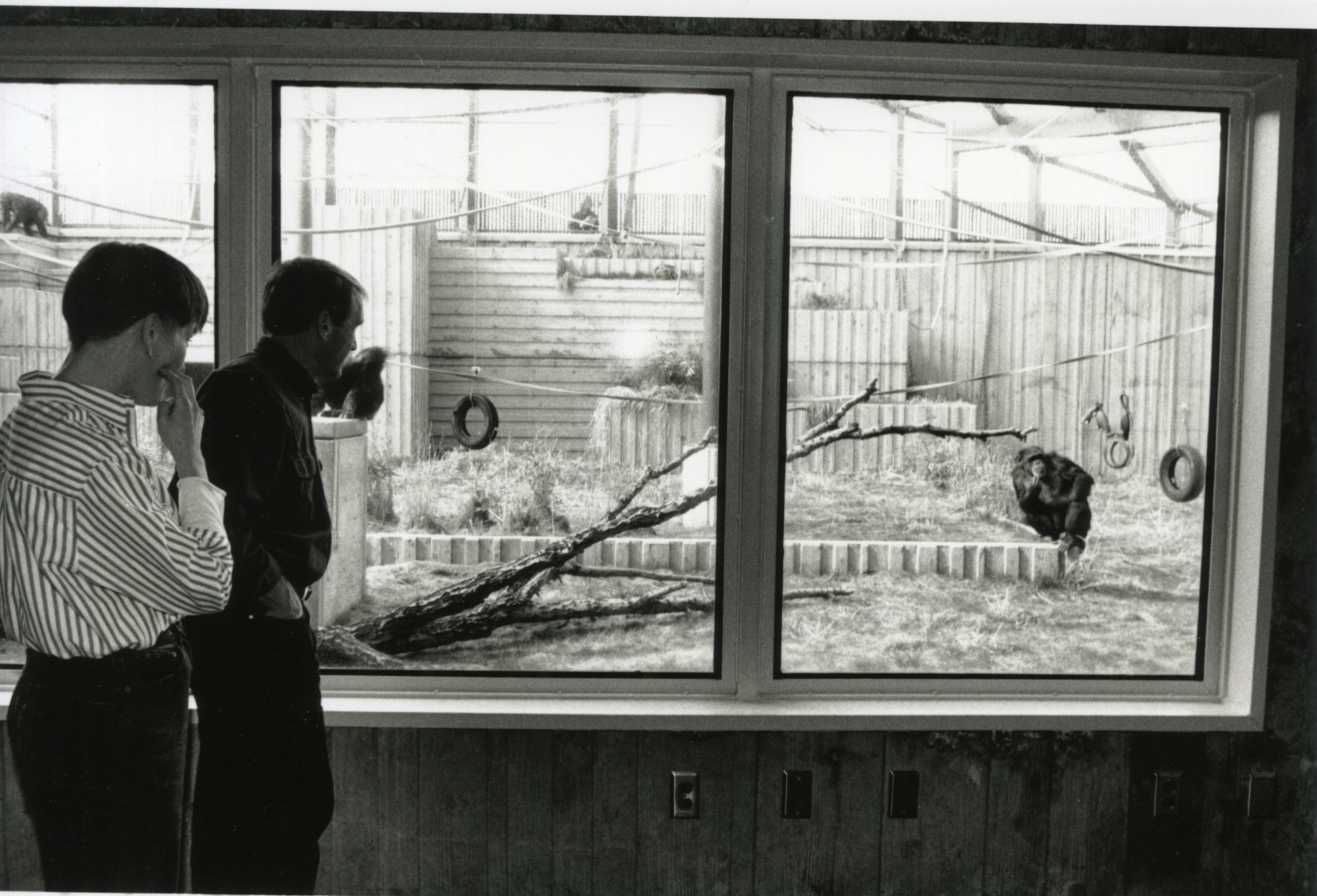

Their presence is highly out of the ordinary. Fauna is not a zoo, and it is only open to interested members of the public once a year. Fauna Foundation’s land has been designated as a nature reserve by the provincial government. It’s a pleasant place for a chimpanzee to retire, and that’s the goal, Jensvold explains. The chimps are prevented from procreating, and eventually, there will be no chimps left here. Tatu, Loulis, and the one other chimp at Fauna, a survivor of biomedical experiments, are the only three chimpanzees in Canada, and that number will ideally dwindle to zero.

Much was learned about chimpanzees’ ability to communicate, and humanity’s own evolution toward language, from the cross-fostering experiments. But it involved using these animals, tearing them away from their own kind, their own homes. Was it worth it?

Not all those who have studied chimpanzee communication have the same answer. Yannick Becker, a postdoc at the Max Planck Institute for Human Cognitive and Brain Sciences and a colleague of Crockford’s, observes that better treatment of apes was legislated at least partially because of the experiments. Chalcraft sees another silver lining, pointing out that the ASL experiments saved Washoe and several other chimps from medical and military facilities.

Ultimately, without the advocacy of those who worked closely with talking apes, among other efforts, it’s possible there would still be hundreds in labs, where they might be subjected to painful and terrifying conditions.

Jensvold considers the question. Her time with cross-fostered chimps began in 1986, working under Fouts. Since his retirement, she has continued conducting research along the same lines, publishing studies as recently as 2024 showing that despite the deaths of Washoe and others, Tatu and Loulis have continued to sign to each other and their caregivers. Much of her professional life has been dedicated to the study and care of the two remaining chimps and their late companions.

There’s much that can still be learned from the ASL chimps. Enough data has been collected that papers can continue to be published for years after their deaths. But while they’re here, they are ambassadors. Jensvold points to the gasps from the crowd that followed Tatu’s greeting and request for a frozen treat.

“That happens all the time,” she says. “It just helps people to sort of understand that it’s not humans and then the rest of nature.”

Still, she says, “Would I do it again? No.”