How Jane Goodall changed what we know about chimps

Newly revealed images shed light on her research breakthroughs, how she became famous, and the photographer she loved.

“For those of you who may hear a story twice, please forgive me,” Jane Goodall told her audience at a 2015 lecture. But sometimes, she noted, “stories are nice to hear again.” The basic narrative of Jane Goodall’s life is instantly recognizable from the many times it’s been written, broadcast, or otherwise sent into the world: A young Englishwoman conducts chimpanzee research in Africa and winds up revolutionizing primate science. But how did it happen? How did a woman with a passion for animals but no formal background in research navigate the male-dominated worlds of science and media to make enormous discoveries in her field, and become a world-famous face of the conservation movement? This is that story.

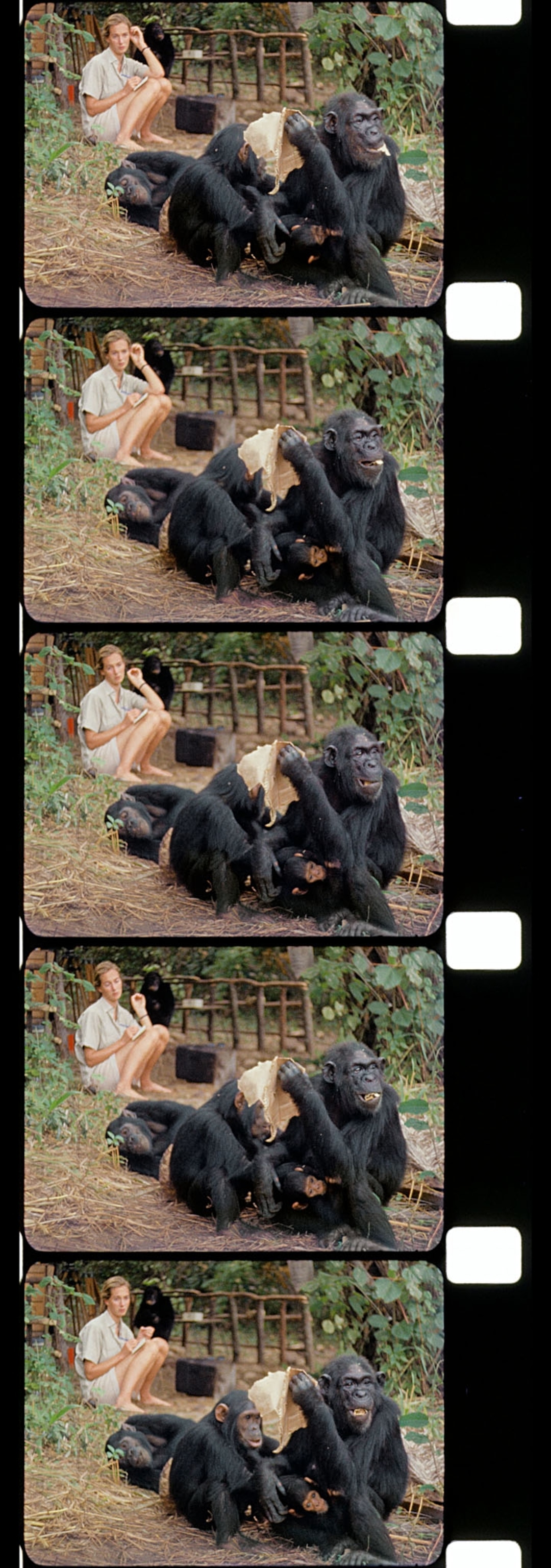

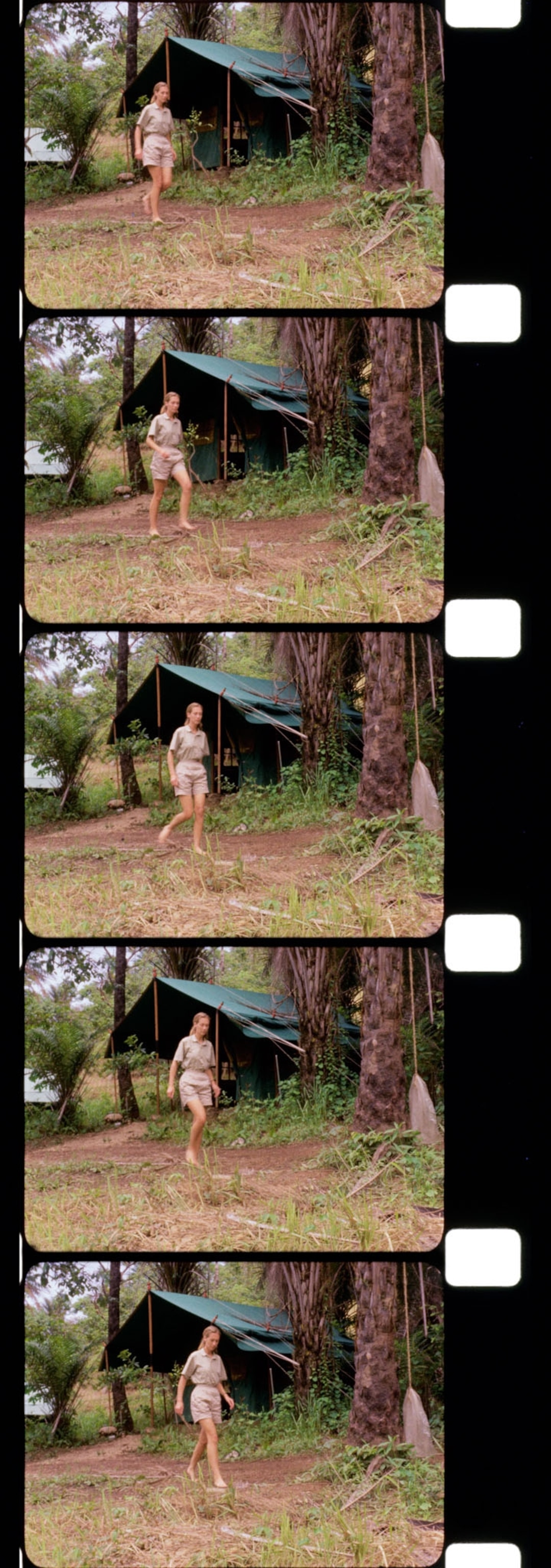

Jane became widely known because of a film, Miss Goodall and the Wild Chimpanzees, which came out in 1965 and was produced by National Geographic. She hasn’t seen it in years. But now I’m playing it for her on a laptop at the West London home of a friend. The primatologist, 83 this year, studies her 28-year-old self.

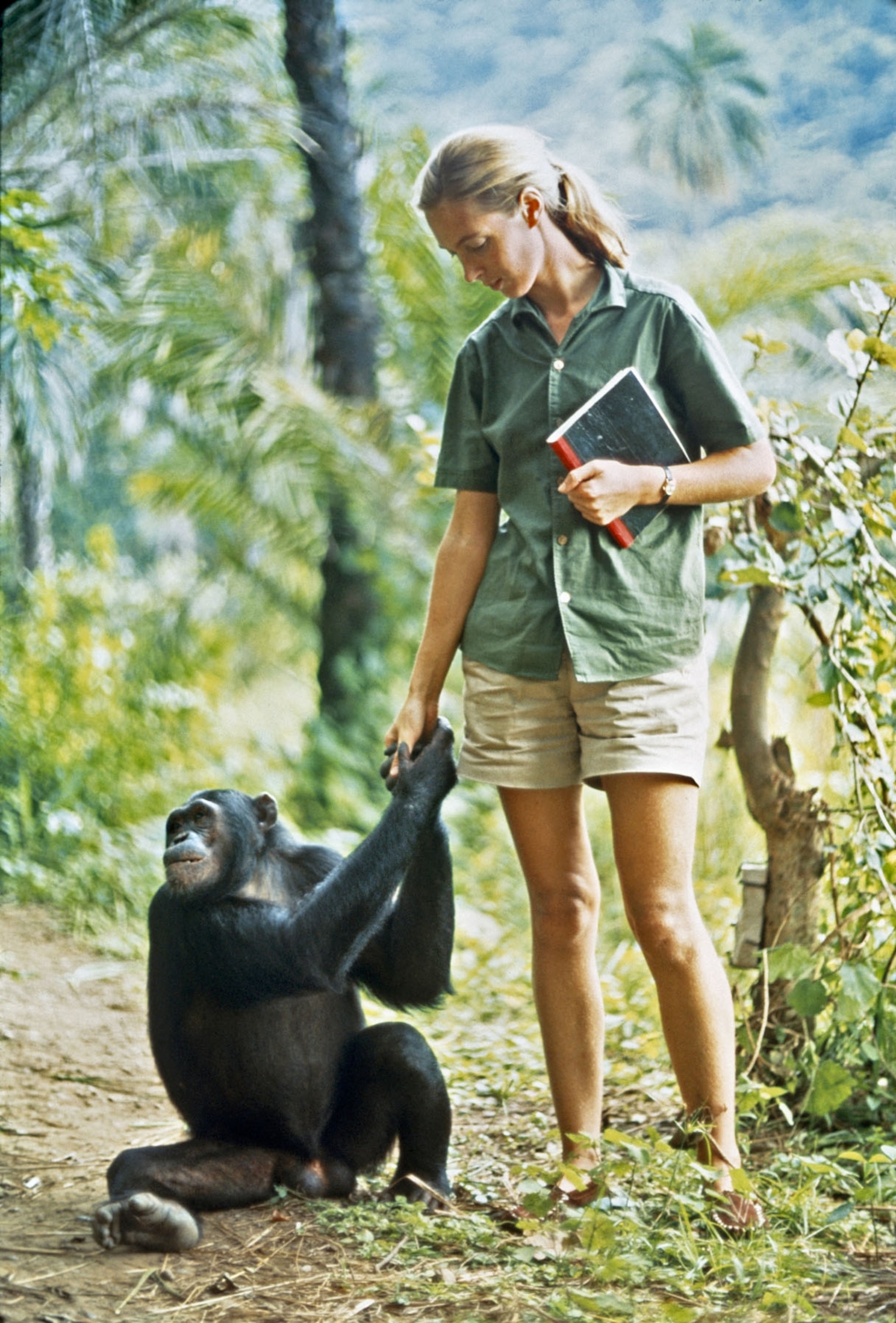

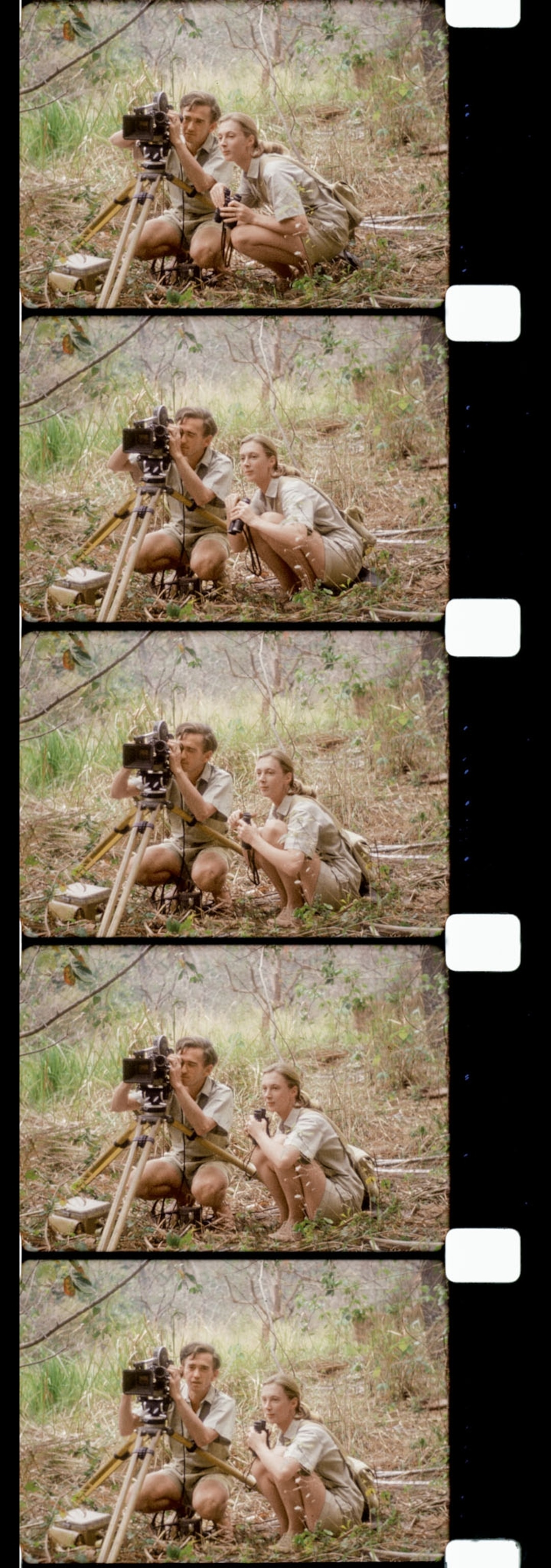

“Think how fun it would be to be that age again,” Jane says with a smile. The young Jane on the screen is hiking through the forest of Gombe Stream Game Reserve in what is now Tanzania. She’s wearing high-top canvas sneakers and khaki shorts, and her blond hair is in the ponytail that became her signature. She appears to be doing field research—but in reality, Jane says, she was reenacting events from her first six months at Gombe so that photographer Hugo van Lawick could film them. Those months had been a remarkable period of solitude and discovery, a time before cameras were present. They’ve been present in her life ever since.

National Geographic executives had specifically told Hugo which shots to get, Jane remembers: “They gave us a list: Jane in the boat, Jane with binoculars, Jane looking at a map.” When Miss Goodall and the Wild Chimpanzees was broadcast on CBS on December 22, 1965, an estimated 25 million North American viewers tuned in—a huge audience, then and now.

The exposure brought Jane international acclaim and ignited what became a legendary career in primatology. In Jane, National Geographic found a telegenic researcher and storyteller with a film-ready setup: an attractive white woman doing scientific work in the African bush. It was especially poignant at a time when women typically were discouraged from pursuing careers in science.

Since then, Jane has completed a Ph.D. at Cambridge University, authored dozens of books, mentored new generations of scientists, promoted conservation in the developing world, and established several sanctuaries for chimps. Today the Jane Goodall Institute’s Roots & Shoots program is in nearly a hundred countries, training young people to be conservation leaders. And Jane still travels about 300 days a year to lobby governments, visit schools, and give speeches.

Jane has been the subject of more than 40 films and has made countless appearances on television. Now she is the subject of a new National Geographic Documentary Films release about her life and work. The two-hour feature, JANE, draws from never before seen footage to offer a revealing portrait of the woman whose devotion to chimpanzees made her famous.

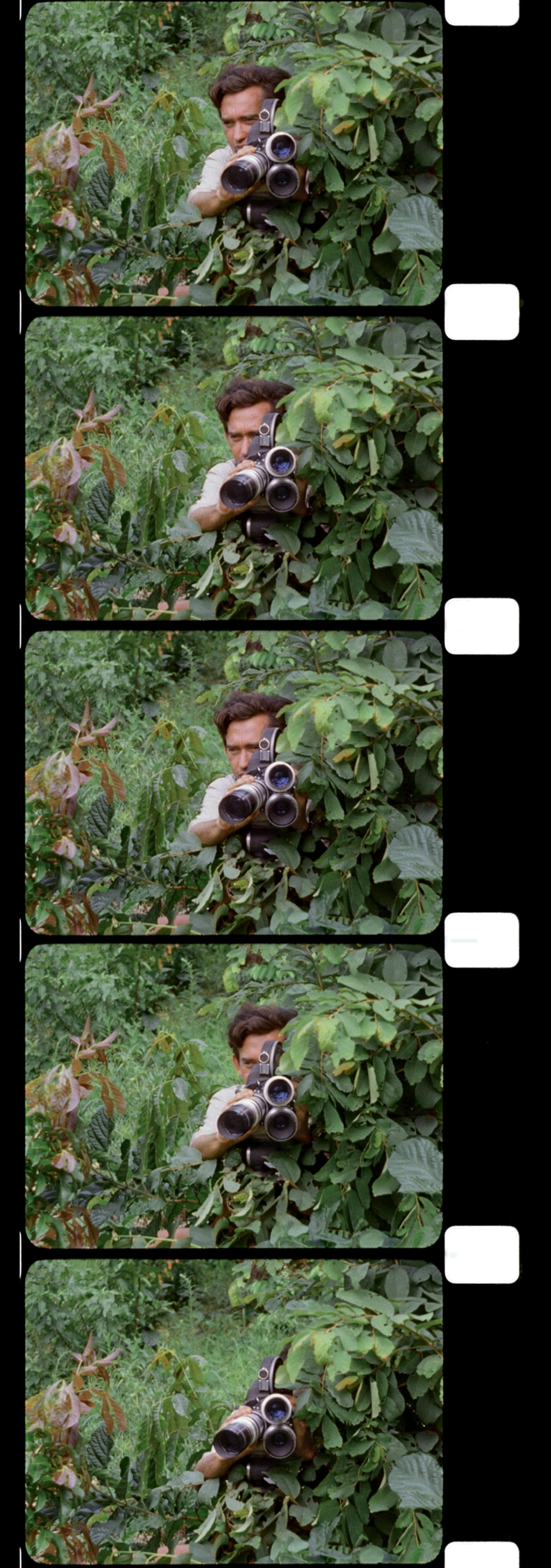

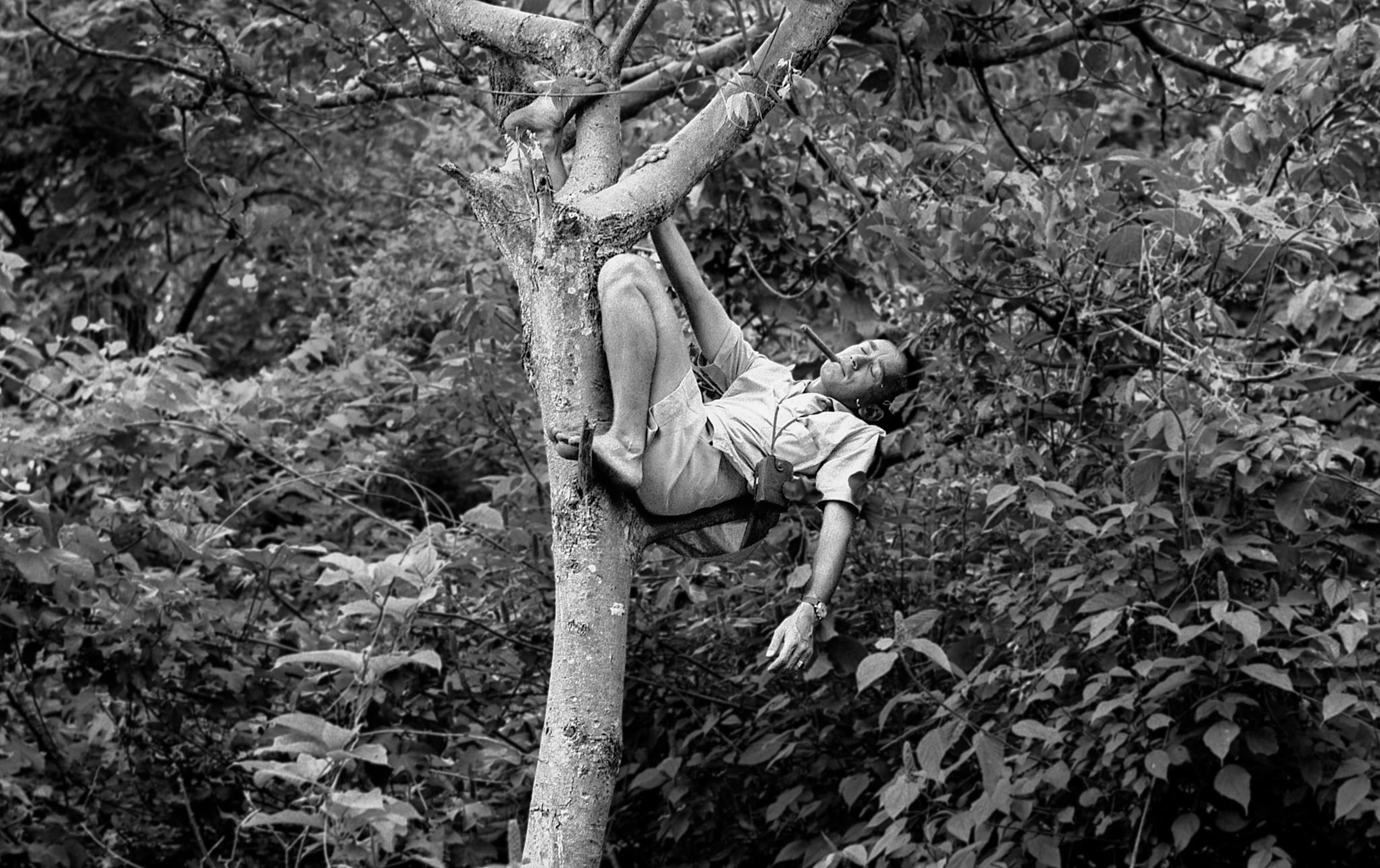

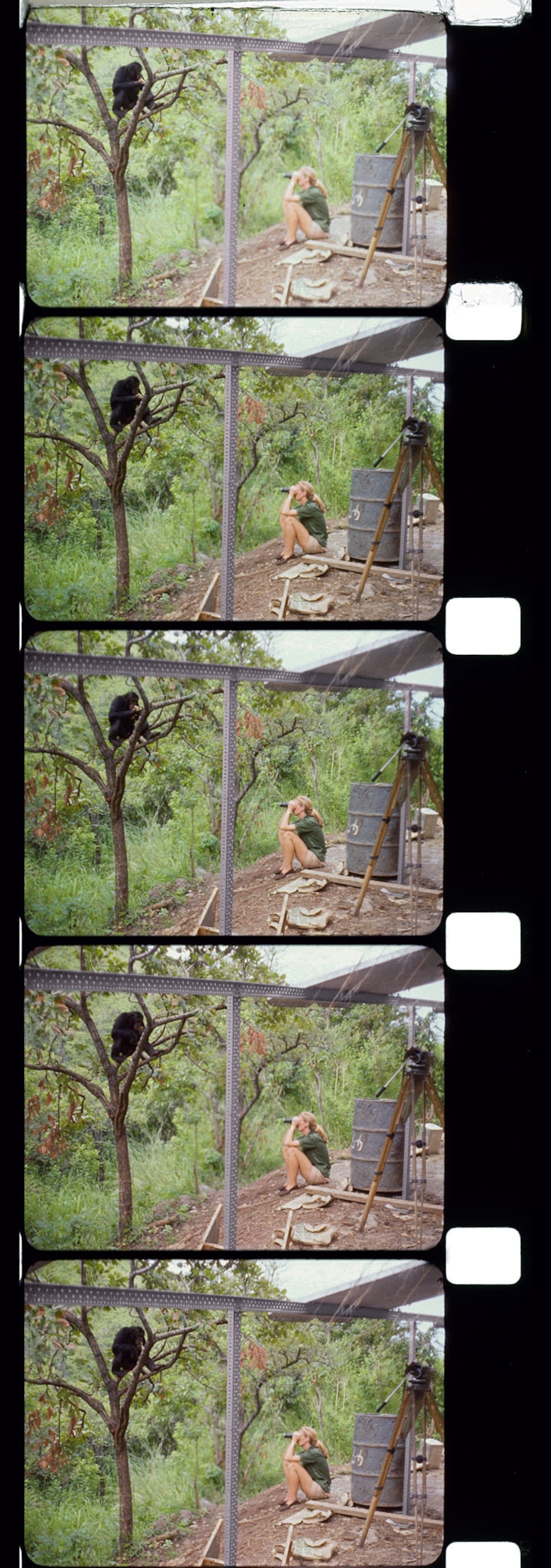

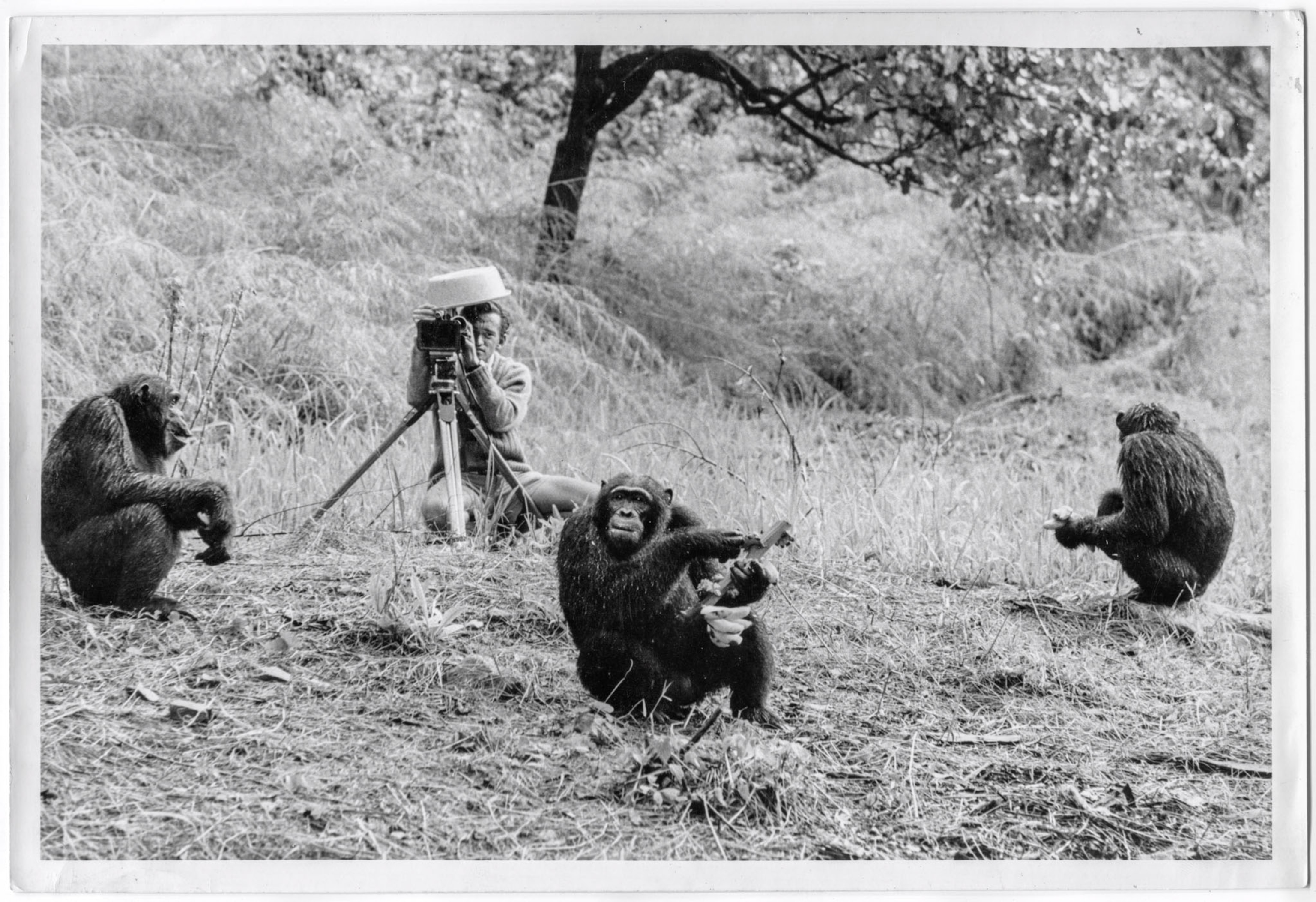

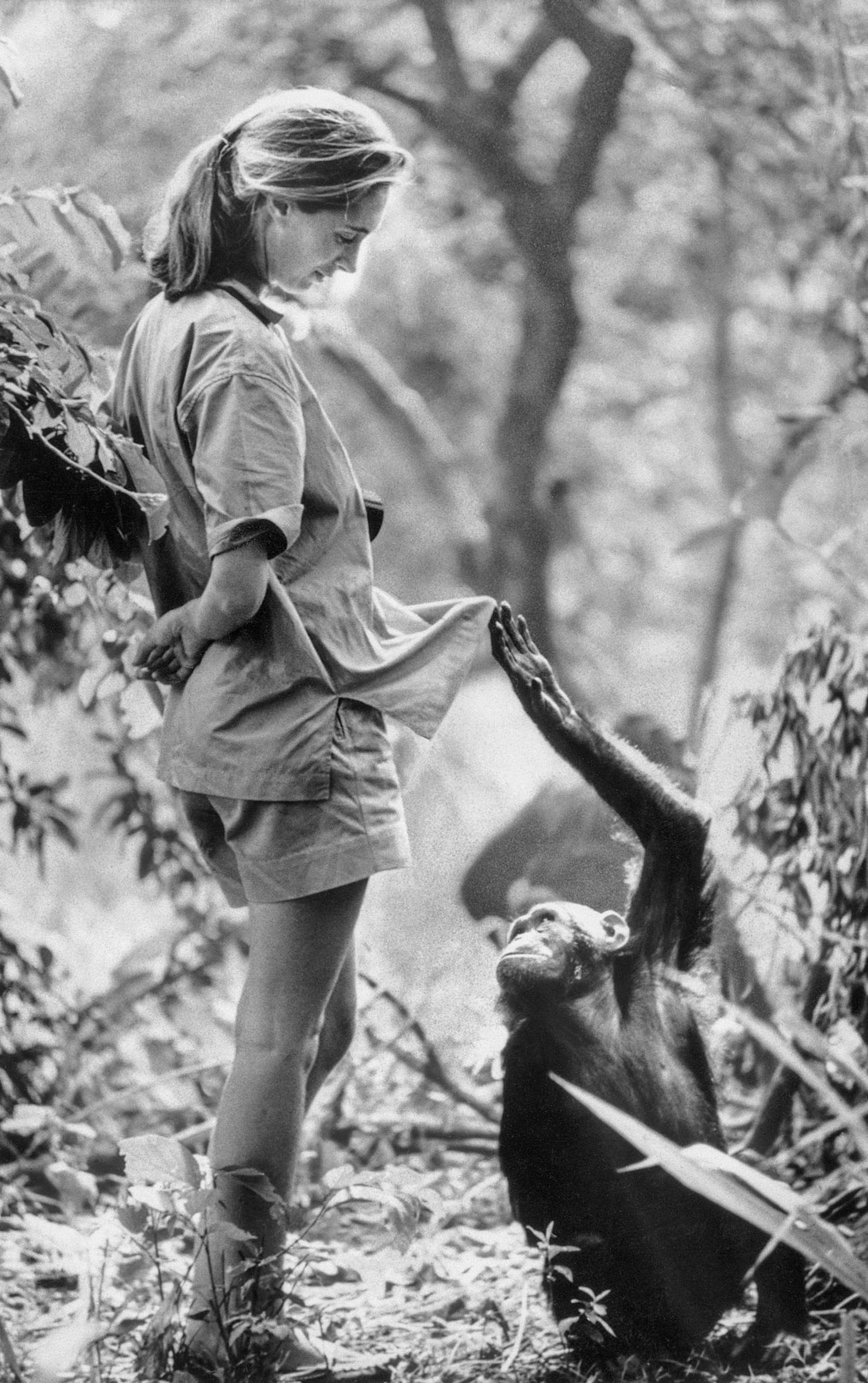

When Hugo first went to Gombe in 1962 to document Jane’s discoveries, he shot thousands of still images and more than 65 hours of 16mm film footage. A fraction of the work made its way into the 1965 television special and National Geographic magazine. What the editors didn’t use, the outtakes, went into film cans and boxes for storage and over time were forgotten. In 2015 they were found in an underground storage facility in rural Pennsylvania. These precious rolls of film held the promise of something rare: a new perspective on Jane. On film, every so often at the end of a take, she drops her serious persona and glances directly at the lens—toward Hugo, her director. In these few instances, we see the stirrings of love for the man behind the camera.

Taken together, this trove of material provides an intimate view of Jane at a pivotal time: When a young woman who had known Africa only from Tarzan and Dr. Dolittle books was dropped into her fantasy, and when a novice scientist’s discoveries debunked long-held beliefs about humans’ closest living relatives.

At Gombe, Jane withstood all manner of natural threats: malaria, parasites, snakes, storms. But in her dealings with the wider world, the challenges often required shrewd strategy and delicate diplomacy. Early in her career, Jane had to contend with a primarily male science establishment that didn’t take her seriously; with media executives whose support hinged on her willingness to be scripted and glamorized; with men who said they’d be her partner or patron but also sought control, concessions, or relationships that she did not want.

Through it all, Jane’s philosophy seemed the same: She would endure slights, accommodate demands, tolerate fools, make sacrifices—if it served to sustain her work.

From her childhood in England, Valerie Jane Morris-Goodall professed a deep love of animals and a desire to work with them in Africa. Her family lacked the means to send her to college, so Jane went to secretarial school. She worked at Oxford and then for a documentary film company in London. In the summer of 1956 she returned home, where she waited tables to save for an ocean passage to Kenya.

In Nairobi she boldly asked for an appointment with paleoanthropologist Louis S. B. Leakey, whose interest in great apes grew from his pioneering research into human origins. Leakey hired Jane on the spot to do secretarial work and saw in her the makings of a scientist. He arranged for her to study primates while he raised funds so she could conduct chimpanzee field research in Tanzania.

And within months of their first meeting, he told Jane he was in love with her.

Jane wrote to others that she was “horrified” by the overture from Leakey, who was 30 years her senior and married. For months after Jane told him firmly that she’d never return his feelings, Leakey still sent her love letters.

In an interview years later with Virginia Morell, author of a book on the Leakey family, Jane said that “what I was most afraid of was what my rejection of him might mean for my study of the chimpanzees.” But Leakey never withdrew his support—and by the summer of 1960 Jane was setting up camp in the Gombe Stream Reserve near the shores of Lake Tanganyika, with enough funding for six months of fieldwork. Because government officials wouldn’t allow a lone female to live in the reserve, Vanne Morris-Goodall came along as her daughter’s chaperone.

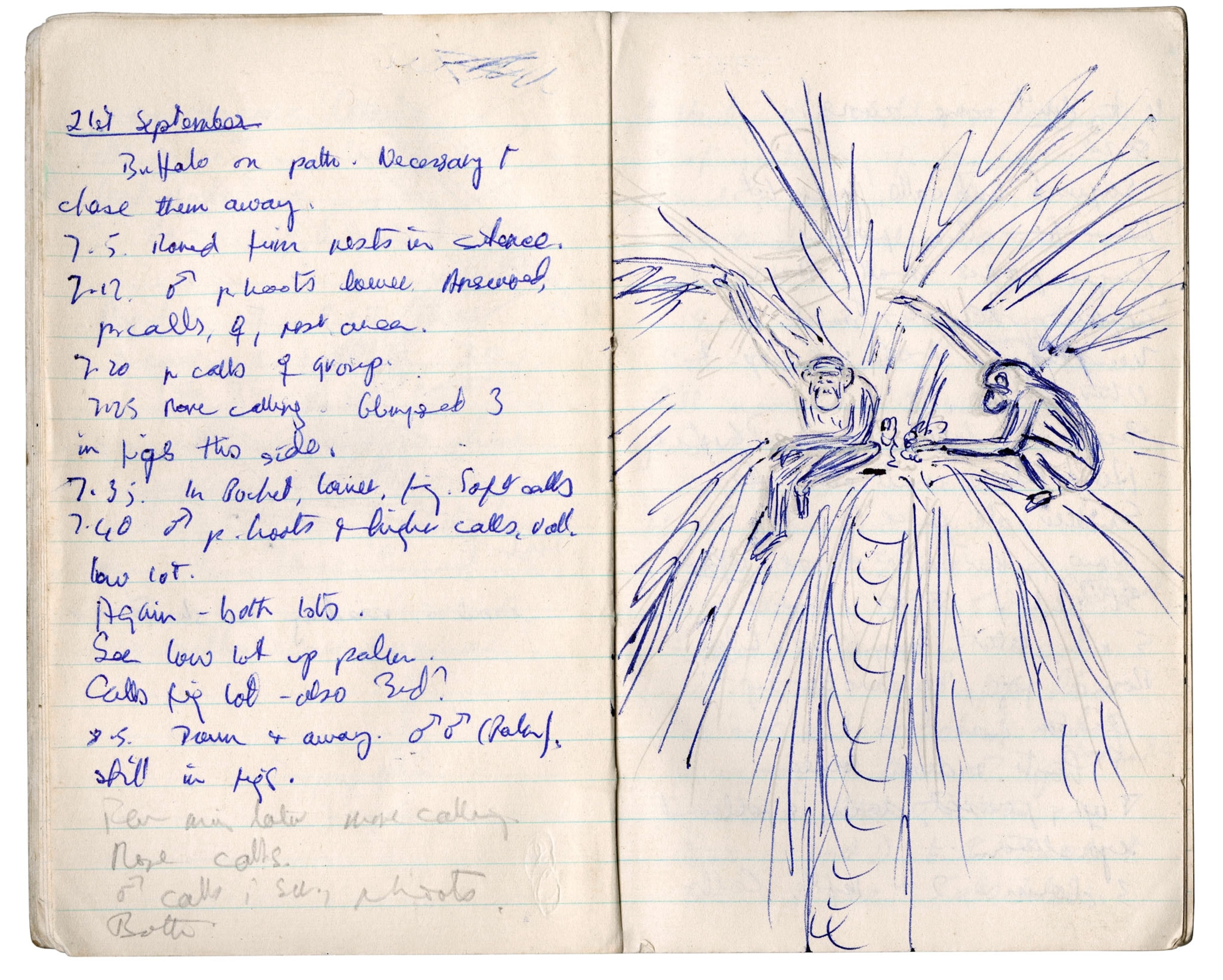

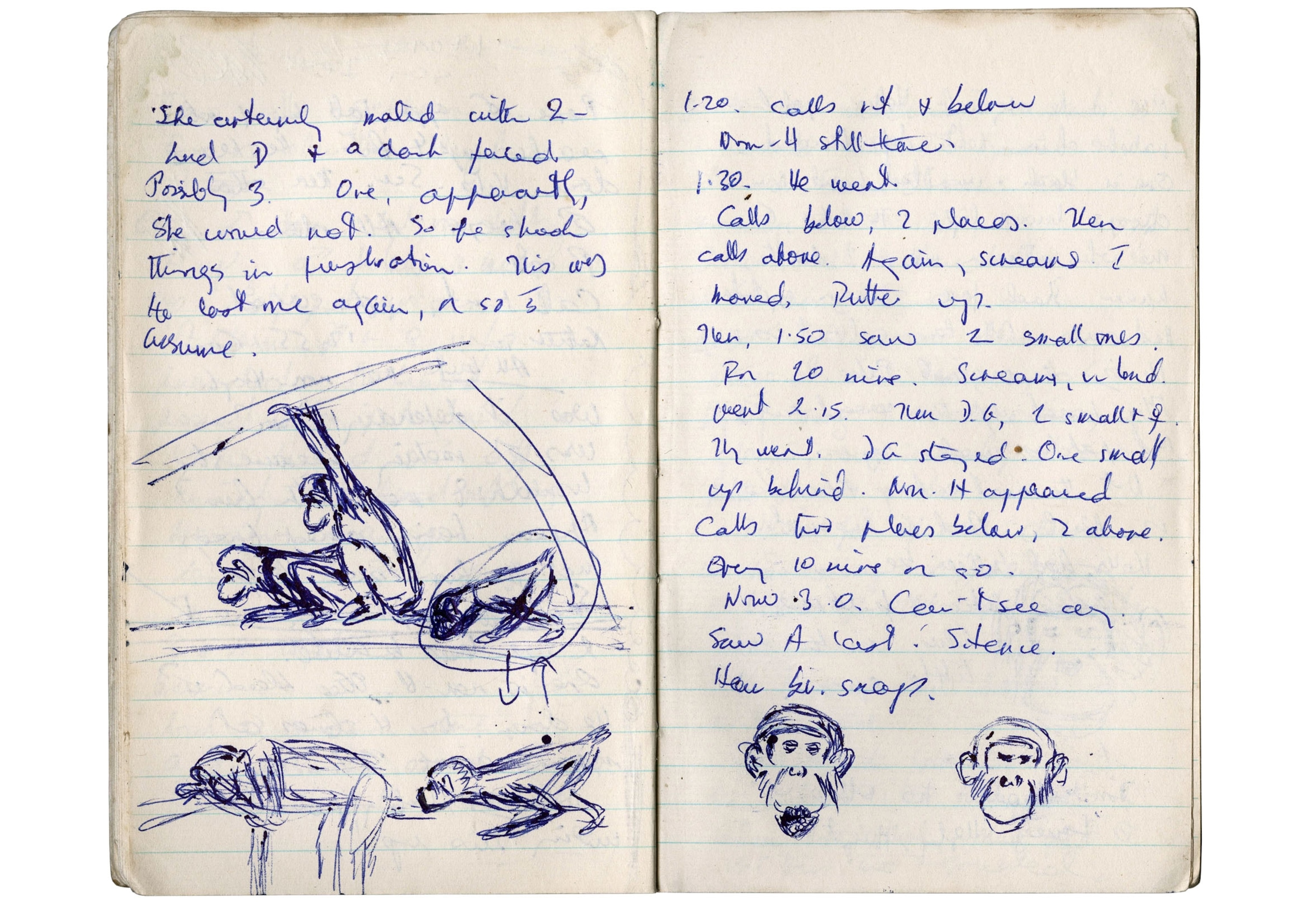

From the start Jane followed her instincts for conducting research. Not knowing that the established scientific practice was to use numbers to identify animals under study, she recorded observations of the chimps by names she concocted: Fifi, Flo, Mr. McGregor, David Greybeard. She wrote about the chimps as individuals with distinct traits and personalities—for example, when a female she called Mrs. Maggs was preparing a treetop nest for the night, Jane wrote that the chimp had “tested the branches exactly the way a person tests the springs of a hotel bed.”

She spent most waking hours locating the animals through her binoculars, then trying to draw gradually closer so they’d get used to her presence as she sat jotting notes. But with one month left in the study grant, she hadn’t made the kind of significant discovery she felt would justify Leakey’s faith in her.

As her study was approaching its end, Jane made three discoveries that would not only make Leakey proud but would also turn established science on its head.

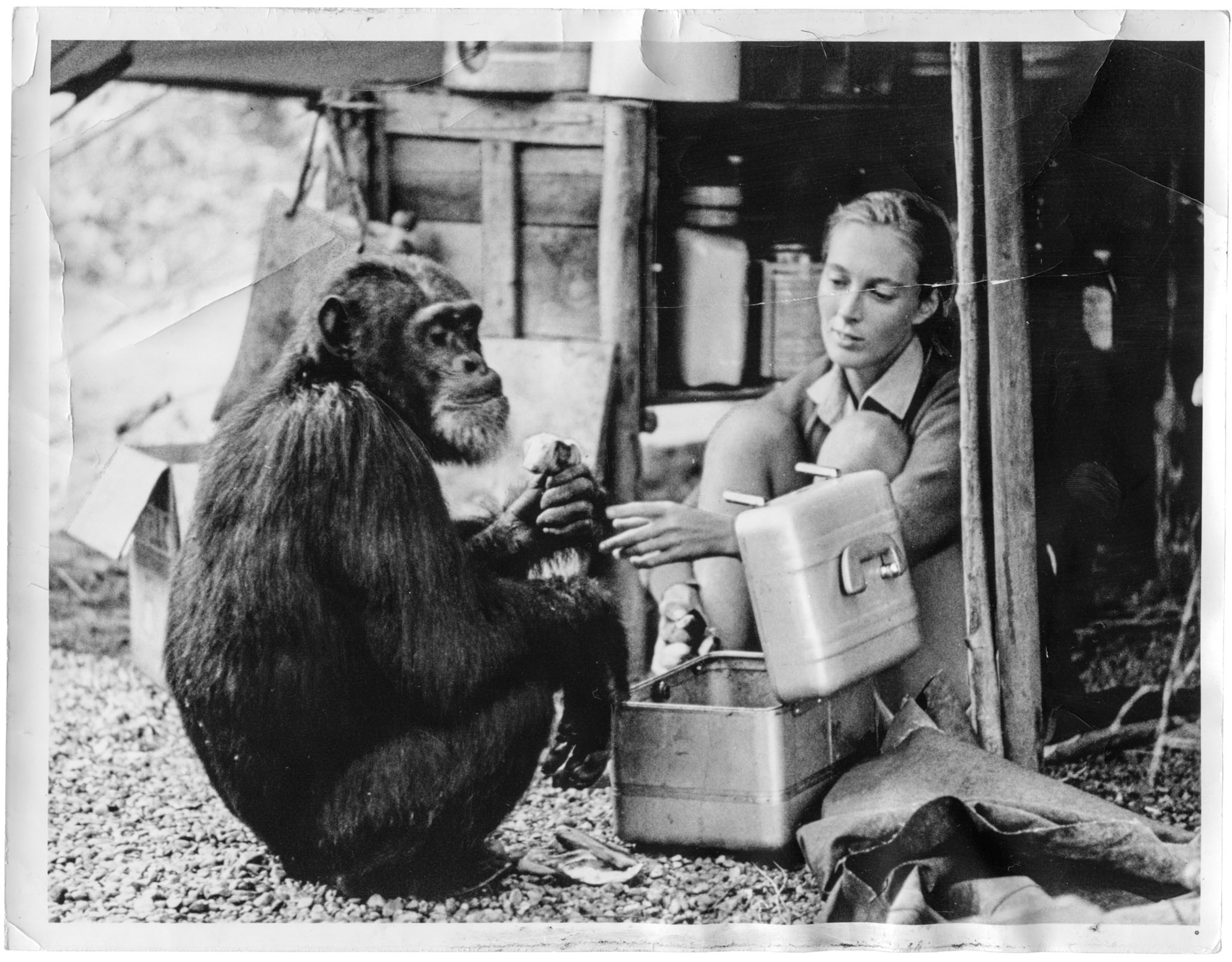

In her first discovery, she observed a chimp gnawing on the carcass of a small animal, which belied the prevailing belief that apes didn’t eat meat. The chimp was memorable for his prominent gray goatee, and she would name him David Greybeard. He in turn would open the door for her to the hidden world of Gombe’s chimpanzees.

Within two weeks Jane observed David Greybeard again, but this time what she witnessed was truly game-changing. Squatting by a termite mound, he picked a blade of grass and poked it into a tunnel. When he pulled it out, it was covered with termites, which he slurped down. In another instance, Jane saw him pick a twig and strip it of leaves before using it to fish for termites. David Greybeard had exhibited tool use and toolmaking—two things that previously only humans were believed capable of.

When Jane cabled the news to Louis Leakey, he sent this response:

NOW WE MUST REDEFINE TOOL STOP

REDEFINE MAN STOP

OR ACCEPT CHIMPANZEES AS HUMAN

In the wake of these discoveries, National Geographic gave Jane a grant to continue her work at Gombe.

As Jane began to write up and publish her field research, she met with skepticism from the scientific community. After all, she had no science training—no degree other than a secretarial certificate affirming that she could touch-type.

In the spring of 1962, Jane gave a presentation at the Zoological Society of London’s primate symposium and impressed many in attendance, including zoologist and author Desmond Morris. But she also faced derision. A society officer delivered a thinly veiled critique of her work as “anecdote and … speculation” that made no “real contribution to science.” An Associated Press report began with this: “A willowy blonde with more time for monkeys than men told today how she spent 15 months in the jungle to study the habits of the apes.”

A photographic record of Jane’s discoveries would put them beyond dispute. But Jane rebuffed National Geographic’s request to send a photographer, saying a stranger might disrupt the relationship she was building with the chimps. After spending months getting close enough to even be in camera range, “I want to do my own photos—or have a jolly good try,” she wrote in a letter home.

National Geographic shipped a camera and several rolls of film to Africa with detailed instructions on how to use them. Jane made a valiant effort. But her dark-furred subjects tended to hide in the shadows, and the photos she submitted weren’t up to the magazine editors’ standards. Again, editors pressed to send a Geographic photographer, and again Jane held them off: Her younger sister, Judy, had photography experience, and the two looked and sounded enough alike that the chimps might not be upset by the sister’s presence.

Louis Leakey underwrote Judy’s trip to Gombe, covering the expense by selling rights to print the first pictures to a British weekly. Ultimately the Geographic’s editors found her photos unsatisfactory too.

National Geographic magazine wanted Jane to write an article about her work—but it couldn’t go forward without “good pictures of the animals,” an editor warned. Jane understood that if she couldn’t get her work covered in the magazine, her funding from the National Geographic Society could be in jeopardy.

Leakey had helped Jane get into a Ph.D. program at Cambridge University—she was one of the few individuals without an undergraduate degree to ever be admitted—and he asked National Geographic to support Jane as she wrote up her Gombe research and worked on her dissertation.

When the Geographic turned down the request, saying, “this lady … is unqualified in the sense that she holds no degree of any university,” an outraged Leakey fired off a memo listing her accomplishments. National Geographic officials gave Jane the requested grant, but as part of the deal, she agreed to welcome a professional photographer to Gombe. On Leakey’s recommendation, National Geographic hired Hugo van Lawick for the job.

The opportunity to work at Gombe with Jane would be a huge break for the 25-year-old Dutchman, who had some experience in natural history filmmaking. Jane wrote to a friend that she actually looked forward to his arrival because she’d been told that Hugo was “a first-class photographer, wonderful with animals—well, it’s just too good to be true.”

When I interviewed Jane in 2015, she insisted that “Louis was definitely matchmaking when he sent Hugo. There’s no question, and he admitted it.” Jane believes that Leakey’s enduring love for her was selfless in the end.

Hugo reached Gombe in August 1962. He smoked heavily; Jane detested the habit. Otherwise they were well matched, both ardent observers of wildlife and devoted to their work. In a letter to a friend, Jane wrote, “We are a very happy family. Hugo is charming and we get on very well.”

As Jane and Hugo documented the chimps’ behavior, neither felt it worthwhile to focus on Jane as well. But National Geographic executives were increasingly eager to turn the camera on her.

“I know you won’t forget to get some pictures of straight camp life—cooking, the writing of reports into the night by lamp light, bathing, hair washing and the like,” assistant illustrations editor Robert Gilka wrote in a letter to Hugo in the fall of 1962. “I bring up the hair washing bit because there came out of Jane’s last trip to the chimp reserve just such a picture, but it was … so underexposed that it would not reproduce.” Good shots of Jane washing her hair in a stream, Gilka stressed, “would be a big help.”

In the London home where Miss Goodall and the Wild Chimpanzees is still playing on the laptop, we’ve come to the hair-washing scene. Even today, it doesn’t sit well with Jane.

“I was angry they filmed this,” she says.

Why? I ask.

“I don’t see why people should see me washing my hair. I couldn’t see why it was interesting.”

Hugo’s work pleased National Geographic’s editors. He was checking off the boxes: capturing photographic proof of the chimps’ toolmaking and use, nestbuilding, social hierarchies—and dutifully taking the human interest shots of Jane that Gilka had requested.

His photographs appeared with Jane’s words in National Geographic magazine’s August 1963 cover story, “My Life Among Wild Chimpanzees: A courageous young British scientist lives among these great apes in Tanganyika and learns hitherto unknown details of their behavior.”

The issue was a resounding success. National Geographic Society President Melville Grosvenor paid Jane and Hugo bonuses and called the article “magnificent.” On its first page, a short text introducing Jane captured the duality of the public image being crafted for her. In one paragraph, she was called “a modern scientific zoologist”—and in the next, “a charming young Englishwoman.”

As Jane and Hugo expanded the research station at Gombe, they also developed ideas for new films, but National Geographic wanted to keep the spotlight on Jane in films being made for television and the lecture circuit. The requests were increasingly specific, as in this letter to Hugo from Joanne Hess of the National Geographic Society’s lecture branch:

“It will be most important and helpful to have several shots of Jane, which you will have to pose, showing her looking through binoculars, laughing at chimps, staring up at chimps in trees, staring into distance at chimps, and writing notes in her book, etc.,” Hess wrote. “I mean you should take about 200 feet of close-ups of Jane ‘pretending’ to do these things, so that we can cut pictures of her into the film.”

The pressures to pose rankled Jane, but she handled it diplomatically. In a letter to Melvin Payne, whose National Geographic committee oversaw her funding, Jane wrote, “Certainly I understand that it is necessary to build up a story around ‘Jane Goodall’ and we have cooperated with Joanne as much as we possibly could.”

But when Hess came to Gombe to oversee some filming, Jane allowed herself a private act of rebellion. “We are already collecting large numbers of evil looking spiders and centipedes to lay around casually in her tent, in an endeavor to shorten her visit,” Jane wrote to her mother.

When I interviewed Jane years later, during a 2015 visit to Gombe, she could look back on the celebrity treatment more philosophically:

GOODALL: There’s this glamorous young girl out in the jungle with potentially dangerous animals. People like romanticizing, and people were looking at me as though I was that myth that they had created in their mind. And the Geographic helped create it too.

GERBER: A lot of people would resist that and fight back and say, That’s not me.

GOODALL: There was nothing I could do about it because as far as they knew, it was me. And there was no way I could be portrayed differently. It wasn’t inaccurate. It’s just that people take the facts and weave stories around them.

GERBER: But at some point you embraced it? You embellished it? You made it better?

GOODALL: Well, at some point I realized that if people were going to think this way, then they would listen to me, which is true. And this would help to conserve chimps and do all the other things I need to do.

As 1963 ended, Jane confided to friends that she and Hugo were “very much in love.” During Christmas holidays at her family home in Bournemouth, on England’s southern coast, she received a telegram: “WILL YOU MARRY ME STOP HUGO.” She replied yes. They set March 28 as the wedding date, one month after what would be another red-letter day for Jane: her first major public lecture in the United States.

Jane was a little nervous about being on stage at the 3,700-seat DAR Constitution Hall in Washington, but the members of National Geographic’s lecture committee seemed more nervous. She was to give her remarks against the backdrop of a film made from Hugo’s Gombe footage. As the February 28 event neared, the committee asked for a draft of her speech. Jane hadn’t written one.

Seeking assurance that the lecture would go well, Joanne Hess and her team asked Jane to join them in the editing room, to practice her remarks as the film played. When I interviewed her at Gombe in 2015, she recalled the scene:

“The Geographic naturally wanted to hear what it would be like,” she recalled. “Well, it’s very hard for me to practice something ahead; it comes out to the audience. I didn’t know that then. I just knew that with three people listening to me in that cutting room, this isn’t a lecture! Apparently they were all whispering to each other, ‘Shall we cancel it? It’s going to be a disaster! Can we really have the Geographic associated with this young gal? She doesn’t seem to know what she’s going to say.’ I had every idea what I was going to say, but I wasn’t going to give a whole speech to three people in a cutting room.”

In her speech and film presentation at Constitution Hall, Jane reported on her scientific discoveries, which she called “results beyond my wildest dreams.” She evoked scenes of Gombe’s beauty and tranquility. And as she would throughout her career, she described chimps by their personalities and the names she’d given them. She called Fifi “agile and acrobatic” and described Fifi’s older brother Figan as an adolescent who “feels he’s a little bit superior.” To a baby who was “just beginning to find her feet,” Jane had impishly given the name Gilka, after the National Geographic editor.

And in describing the need to protect the chimps and prevent them from being shot or sold to circuses, Jane referred to David Greybeard, the trusting chimp who had opened the door to some of her most important discoveries.

“David Greybeard … has put his complete trust in man,” she told the audience. “Shall we fail him? Surely it’s up to us to do something to ensure that at least some of these fantastic, almost human creatures continue to live undisturbed in their natural habitat.”

Her presentation was a triumph, and a milestone in her emergence as a public figure—a status she didn’t start out seeking but was learning to manage to her advantage. It caught the attention of a National Geographic executive who was launching a television specials division. A good deal of the Gombe footage ended up in one of the division’s first prime-time broadcasts: Miss Goodall and the Wild Chimpanzees, with narration by Hollywood luminary Orson Welles.

When Hugo and Jane first screened the finished film, they complained of its many inaccuracies. They found the Welles narration patently unscientific—and at Jane’s insistence, the script was partially rewritten.

To this day, as she watches the film on the laptop, Jane points out flaws. That leopard wasn’t photographed by Hugo, it was stock footage. That scene isn’t in Gombe, it’s somewhere in the Serengeti. And when Welles begins a sentence with “After two months’ search in vain,” Jane cuts him off: “It wasn’t true that I didn’t see any chimps for two months. That’s an absolute lie.”

The flaws seemed to matter only to Jane and Hugo; the film was a commercial success. The two hoped they might do another film project and have more creative control, but Geographic officials had other ideas. They wanted to do more with Jane and Gombe, but not necessarily with Hugo. Jane was their star; Hugo, an accessory.

In the years after the filming at Gombe, Jane and Hugo took different paths. In 1967 Hugo and Jane welcomed a son, Hugo Eric Louis van Lawick, known by his nickname, Grub.

With Jane’s work anchored in Gombe and Hugo’s filmmaking passion in the Serengeti, nearly 400 miles away, the two grew apart. In 1974 Jane and Hugo divorced. In 1975 she married Derek Bryceson, a Tanzanian government official.

By the time Grub was eight, he was living with his grandmother and attending school in Bournemouth. Derek and Jane had been married for only five years when he died of cancer in 1980. After a career spanning four decades, Hugo died of emphysema in 2002.

When I interviewed Jane in Gombe, it had been 55 years since she’d climbed out of a skiff and onto a pebble beach there for the first time. In her mind’s eye she can see things as they were then, from that beach up to the high ridge known as the peak: “It’s like another life, so long ago.”

She can even watch herself pretending, and today recount it with a smile.

In the film footage, Jane sees her 28-year-old self seated on the peak. It’s magic hour, nightfall. Hugo’s exposure is perfect. On screen, Jane pulls a blanket around her shoulders. She raises a tin cup to her mouth and sips.

Now it’s Jane who’s the narrator.

“That cup is empty, I swear,” she says. “There’s nothing inside it.”

Directed by Brett Morgen with music by composer Philip Glass, the feature documentary "Jane" uses never before seen footage to tell Goodall’s life story. Stream the film now on Disney+.