‘Chanel No. 5 of Christmas trees’ threatened by poachers

The endangered Guatemalan pinabete fir is prized for its scent, making it a target of tree thieves and the police who hunt them this holiday season.

CHIMALTENANGO, GUATEMALA — Felipe Lares moved quietly up the mountain in the fog-thickened darkness, a loaded shotgun slung across his back. It was nearly midnight when he stopped at the top of a ridge and waited, listening intently for the faintest sound in the fir forest that might signal the presence of tree poachers.

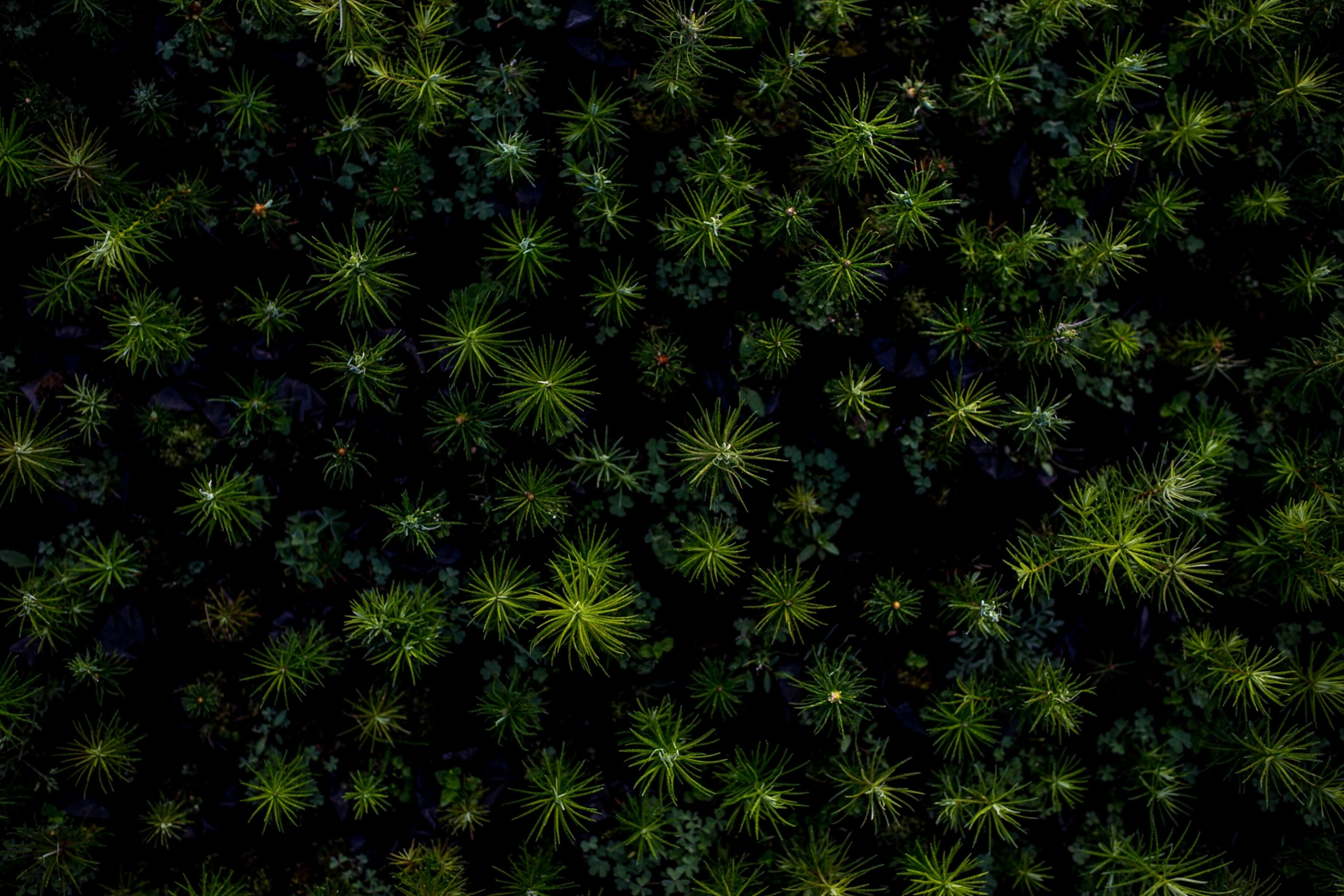

Just decades ago, the Guatemalan fir, known colloquially as the pinabete, was widespread throughout the misty Central American highlands. Today, it’s considered an endangered species. Habitat destruction and exploitation for timber greatly reduced the pinabete’s numbers during the past century, but the biggest threat now comes from an unexpected source: Christmas.

The pinabete, or Abies guatemalensis, is the southernmost member of the Abies genus, composed of about 50 species of the evergreen coniferous trees many of us refer to collectively as “Christmas trees” for their pleasant scent and distinctive shape.

“Pinabetes have been used for ceremonial purposes by indigenous cultures for centuries, but it’s only recently that people have started to use them for Christmas decorations,” says César Beltetón, forestry director of Guatemala’s Council of National Protected Areas, which administers Guatemala’s national parks.

Unlike other Christmas tree species, such as the Fraser or Douglas fir, that are grown by the millions in all 50 U.S. states, the overwhelming majority of Christmas trees in Guatemala are sourced from shrinking natural stands of pinabetes scattered in the high-altitude forests of the mountainous nation. One study estimates that the trees already have been eliminated from as much as 95 percent of their natural range.

Cross-border trade in pinabetes has been banned since 1979 under the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES), the international agreement that regulates trade in wild animals and plants. Domestic trade, however, is legal—but only for pinabetes grown, harvested, and tagged on plantations certified by Guatemalan forestry officials.

In a nation like Guatemala, where local communities often build economic livelihoods around the exploitation of natural resources, and so far, the CITES ban and the rules for domestic trade haven’t staunched the illegal harvesting of pinabetes.

Poachers have taken their business underground, forming “Christmas tree mafias” that cut down millions of young pinabetes and the seed-bearing branches of older specimens every year. As the market has expanded, so has the influence of the traffickers, who, according to Elias Rodríguez Vásquez, chief of Guatemala’s environmental police (DIPRONA), insulate their empire by bribing corrupt officials and even paying communities to attack law enforcement officers attempting to confiscate poached trees.

As pinabete populations continue to decline, the species could go extinct within decades, according to a report by Global Trees Campaign, an organization dedicated to protecting endangered tree species in their natural habitats.

It’s not only the taking of whole trees that threatens the pinabete but also the uniquely Guatemalan practice of removing the seed-bearing branches from mature trees. The branches are then arranged and nailed around a wooden pole to assemble a perfectly shaped Christmas tree.

Pinabetes reproduce slowly, and to make matters worse, the illegal cutting typically starts around the time a tree’s seeds reach maturity, eliminating practically any chance of natural propagation.

“Although other Abies species may also have rather low seed viability rates, the one observed in the pinabete is remarkably low,” says Marten Sørensen, of the University of Copenhagen, in Denmark. Sørensen and his colleagues have found this to be related to inbreeding—the result of a genetic bottleneck provoked by the human-induced decimation of the species over the years. Scientists like Sørenson hope to overcome this through provenance trials—a plantation experiment involving seeds collected from diverse, isolated populations with the aim of ascertaining the most adaptive and robust individuals.

“PLAN PINABETE”

Guatemalan authorities, hoping to stem the overexploitation of pinabetes, have devised a multipronged strategy that draws on the expertise of conservationists, agronomists, law enforcement, educators, prosecutors, scientists, indigenous groups, and others. Plan Pinabete has evolved into what is perhaps the most widespread and long-term environmental education campaign Guatemala has ever seen.

One facet involves on-the-ground enforcement and interdiction. Each holiday season, hundreds of DIPRONA agents are tasked with intercepting shipments of illegally harvested pinabetes as they make their way to the country’s capital, Guatemala City. Traffickers often go to great lengths to obscure the shipments, creating false compartments in truck beds and tractor trailers and even wrapping the trees in gasoline-soaked blankets to obscure their familiar scent, according to DIPRONA agent Ernesto Ortiz Cruz. Other agents are assigned to patrol remaining pinabete forests.

Despite these crackdowns and growing consumer awareness about the plight of the pinabete, the market has continued to expand. In 2016, agents confiscated some 600,000 pinabetes and branches, an amount that nearly tripled last year to 1.7 million pinabete products, valued at nine million quetzals (almost 1.2 million dollars).

The fact that pinabetes are so slow to reproduce on their own means that reforestation and policing of existing pinabete stands alone are not considered viable approaches to saving the species. Aside from strengthening anti-trafficking measures, forestry official César Beltetón says it’s important that communities who live where the trees grow and depend on money from the illegal harvest, have alternative ways to make a living.

“We should be helping these communities set up projects focused on the sustainable production and commercialization of pinabete seeds and establishing plantations with the purpose of offering trees and Christmas products of legal and sustainable origin to the market,” he says.

PLANTATIONS: NO PANACEA

As demand for pinabetes has risen, so has the number of plantations and nurseries offering sustainably sourced trees under the auspices of Guatemala’s National Forestry Institute and the Council of National Protected Areas.

Salvador Pira was one of the first, in the mid-1980s, to convert his farm, Caleras de Chichivac, into a government-certified pinabete plantation. The farm’s location high in the cold, humid mountains of Tecpán lends itself to these trees, and in the weeks leading up to Christmas, Pira opens Caleras de Chichivac to visitors who come to choose their special Christmas tree.

After spending hours perusing thousands of pinabetes dotting the steep hillsides, the Vallatoro Camas family settle on a bushy, seven-foot tree, priced at around 90 dollars. They look on with excitement as their tree is cut and tagged with a white band and serial number certifying its legal origin.

The availability of certified, plantation-raised trees helps reduce, but isn’t solving, the illegal trade in wild pinabetes. That’s because illegal trees typically sell for about $20, while certified ones can go for $125 or more—well beyond the reach of most Guatemalans.

In recent years, according to Global Trees Campaign, legal pinabetes have represented only about 5 percent of the total Christmas trees sold in Guatemala.

Imported trees from the U.S. and Canada have been equally ineffective in luring buyers away from the endangered pinabete. It’s not just the pinabete’s elongated, deep-green needles that consumers love but also the particularly pungent scent this tree exudes. Salvador Pira calls the pinabete the “Chanel No. 5 of Christmas trees.” Imported species such as the Balsam fir are marketed as aromatic alternatives, but to those who know the pinabete, Pira says, “it’s just not convincing.”

“THEY’RE NOT LETTING ANYTHING IN”

This Christmas season, for the first time, Guatemala City’s Campos de Roosevelt Market, widely known as the main sales venue for illegal pinabetes, is filled with trees from certified plantations. As I walk through the market asking for cheap (in other words, illegal) pinabetes, vendors shake their heads, many even reaching into their coat pockets to pull out official documents confirming the legality of their trees.

“This year, it will be impossible to find an illegal pinabete here,” says vendor Norberto Morroy, gesturing toward a group of DIPRONA officers searching cars. “They’re not letting anything in.”

That’s because the attorney general’s office gave Christmas tree vendors at the Roosevelt Market an ultimatum: Sign a binding legal agreement stating that they won’t sell illegally sourced pinabetes, or the market will be shuttered for good.

For José Boc, an artisan and vendor at the market, and for hundreds of families for whom the pinabete has been a critical source of income over the years, the agreement is a major blow.

“Look around you,” Boc says, pointing to families setting up tree stands out of pieces of salvaged plastic, wood, and tin. “These aren’t rich families. Most us don’t have the investment to purchase wholesale legal pinabetes, and even if we did, the majority of families who come to shop here can’t afford these trees. I don’t know how I’m going to pay for my children’s’ school supplies this year, much less for Christmas dinner.” This year, Boc says he’s selling a few certified trees that he was able to scrape up the money to buy and is experimenting with using alternative species such as pine for his handmade trees.

In late 2017, after the news of several highly publicized arrests of pinabete traffickers, and even of ordinary families buying illegal trees, splashed across Guatemalan media, consumers seem to have become more cautious.

“Sometimes you have to come down hard,” Aura López, an environmental crime prosecutor, says with a shrug. Officially, Guatemala’s Protected Areas Act stipulates 5 to 10 years in prison and fines ranging from about $1,300 to $4,000 dollars for those found guilty of pinabete trafficking. Last year, several sentences and fines were handed out to large-scale pinabete traffickers. “Innocent” buyers, on the other hand, typically are let off with minimal fines.

For the Vela Quiñonez family, just knowing about the risks was enough to steer them away from the illegal trees that decorated their homes in the past. “This year, we started a new tradition of buying the certified pinabetes,” Consuela Quiñonez tells me. “It’s expensive, but it feels good to know we’re not contributing to the problem.”

After combing through Roosevelt Market for an affordable tree, Daniel López ushers his children toward the exit empty-handed. “The cheapest tree we could find here was 450 quetzals,” he says, shaking his head. (That’s about 60 dollars.) “I know the trees are endangered, but that’s a little out of our price range.”

Back in the pinabete forest, as dewdrops began to form on branches, Felipe Lares returned to the guard post below, rubbing his hands to warm them up after handing his shotgun to the next guard on duty. His patrol shift had ended without incident—no signs of any poachers. But in the pre-dawn hours that night, a shot rang out through the otherwise silent forest. As Christmas draws in, Lares warned, they’ll have to be more vigilant than ever.