How a Lowly Hedgehog Raised the Bar on Wildlife Care

Before his death in July, former accountant Les Stocker changed the way we deal with injured animals in the wild.

Les Stocker’s life was inextricably altered in 1976, when he stumbled on an injured hedgehog near his home. Unable to get it help from a local veterinarian, who offered to put it to sleep, Stocker took the little animal home and tended to it himself.

It was the beginning of a 40-year journey that would transform the Brit’s mundane life as an accountant. Before his untimely death from an abdominal aortic aneurism last July, Stocker, 73, had become a world-renowned wildlife treatment expert and had created Europe’s first wildlife teaching hospital, Tiggywinkles.

Although he lacked formal veterinary training, Stocker pioneered wildlife medical care at a time when traditional veterinary medicine focused on treating domesticated animals and pets.

An injured wild animal “had nobody to look after it, nobody seemed to care,’’ Stocker once said. “It was just that feeling that made it quite easy for me to start taking them in.”

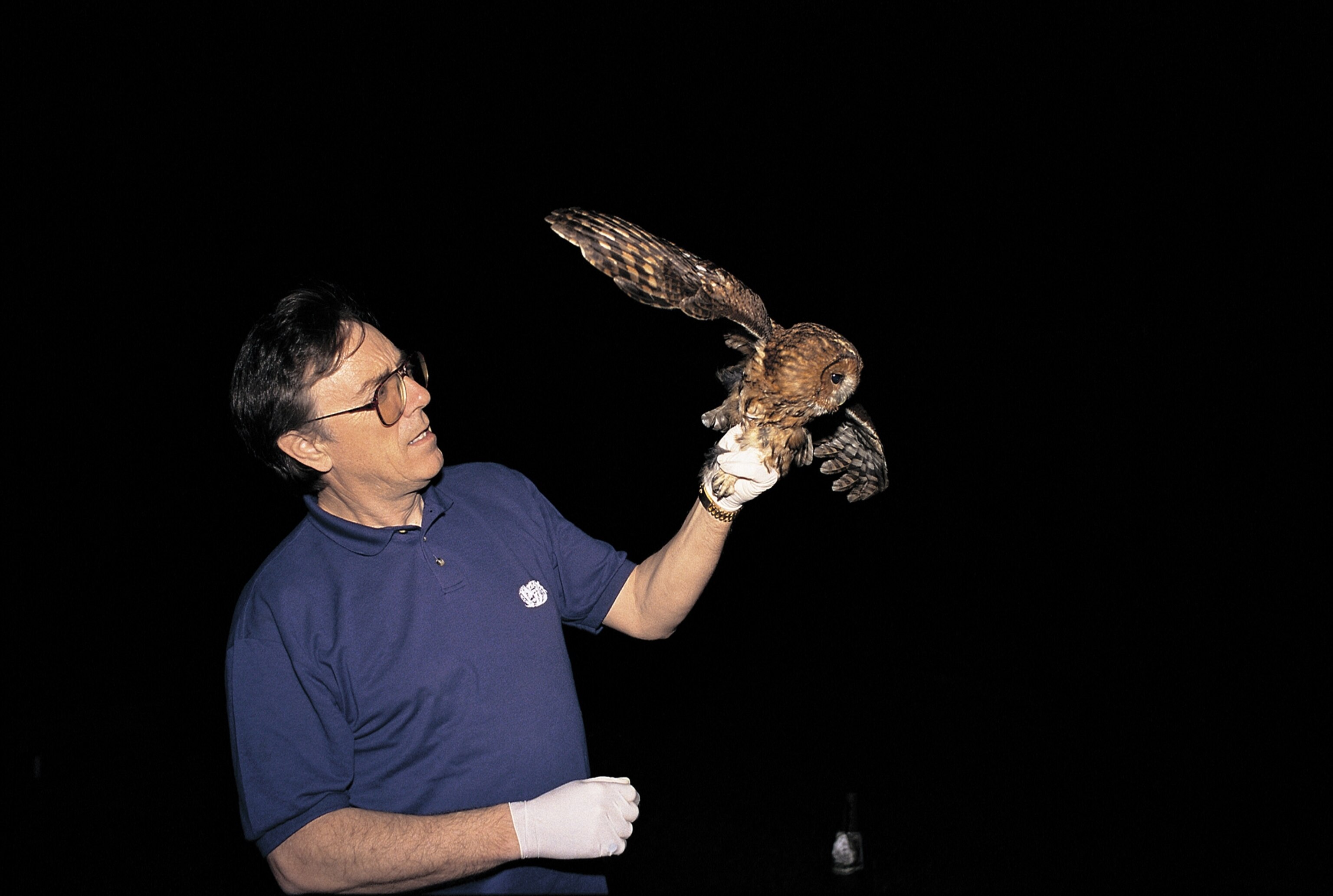

Stocker and his wife, Sue, set up an animal rescue center in a garden shed behind their home in Buckinghamshire, where they began treating a coterie of injured birds and animals—including muntjac deer, foxes, swans, and owls—dropped off by vets, cops, animal shelters, ordinary citizens, and the occasional celebrity. (The late Bee Gees singer Robin Gibb once pulled up in a Rolls-Royce with a partridge hit by a car.)

“Les really changed the public perception about injured wildlife—that if you find something sick or injured, there’s a chance to get it back to the wild,’’ says Tiggywinkles’s director of administration, Andrea Small.

With few established wildlife treatment protocols at the time, Stocker learned by trial and error. He used superglue to repair bird beaks and bat wings. He developed slings to hold and protect injured deer. And he once stitched up a frog’s tongue after it had been sliced by a weed trimmer, then spent hours patiently helping it relearn how to use it to catch insects again. Trained vets were paid to operate and prescribe drugs, but Stocker learned how to provide emergency treatment and anesthetize animals. For baby hedgehogs, he fashioned a plastic cap into an anesthesia mask.

His efforts were eventually honored by the Royal College of Veterinary Surgeons and the New York Academy of Sciences.

By 1983, Stocker was devoted to wildlife full-time, establishing the charitable Wildlife Hospital Trust to fund a veterinary hospital in a converted three-bedroom house. Through donations, the trust eventually raised enough money to build a bigger facility on a six-acre site in 1991.

Named after the popular Beatrix Potter children’s book, Tiggywinkles has a paid staff of 38 and 75 volunteers treating 10,000 wildlife trauma patients a year. Europe's busiest animal hospital, it has 24-hour emergency care, an operating room, a diagnostic lab, an intensive care unit, rehabilitation pools, and a separate wing for hedgehogs, its most numerous patient.

Stocker, a Rolex Laureate, authored the field guide Practical Wildlife Care and Something in a Cardboard Box, a memoir that encouraged volunteerism. He also gained plenty of public adoration and notoriety over the years.

“It never went to his head,’’ says Small, who worked with Stocker for a quarter century.

A reality TV film crew once followed him rescuing an injured badger, “one of many weird and wonderful rescues over the years,’’ Small says.

As Stocker removed the badger from his car trunk, the animal bit his finger. A bloodied Stocker promptly passed out. After he’d been carted off to a hospital by ambulance and awakened, the film crew offered to spare him the embarrassment of airing the incident.

“He was fine with it,’’ Small says. “He had a great dry wit, but underneath, he was determined and passionate about showing how to help wild animals."