Jane Goodall, ambassador for wildlife, dies at 91

Through her groundbreaking work with chimps in Africa, Goodall helped people understand that animals are sentient and intelligent.

Primatologist, ethologist, conservationist, animal advocate, and educator Dr. Jane Goodall, DBE, has died at age 91. The Jane Goodall Institute announced on October 1, 2025, that Goodall, the founder of the Jane Goodall Institute and UN Messenger of Peace, passed away of natural causes.

"Dr. Jane Goodall brought so much light into this world, demonstrating beautifully what one person can achieve," says Jill Tiefenthaler, chief executive officer of the National Geographic Society. "To know Jane was to know an extraordinary scientist, conservationist, humanitarian, educator, mentor and, perhaps most profoundly, an enduring champion for hope.

"A cherished member of the National Geographic community for more than 60 years, Jane forever changed our relationship with nature and, in turn, our own humanity. We are grateful to be among those who learned from her, shared her convictions and will continue to carry her light forward.”

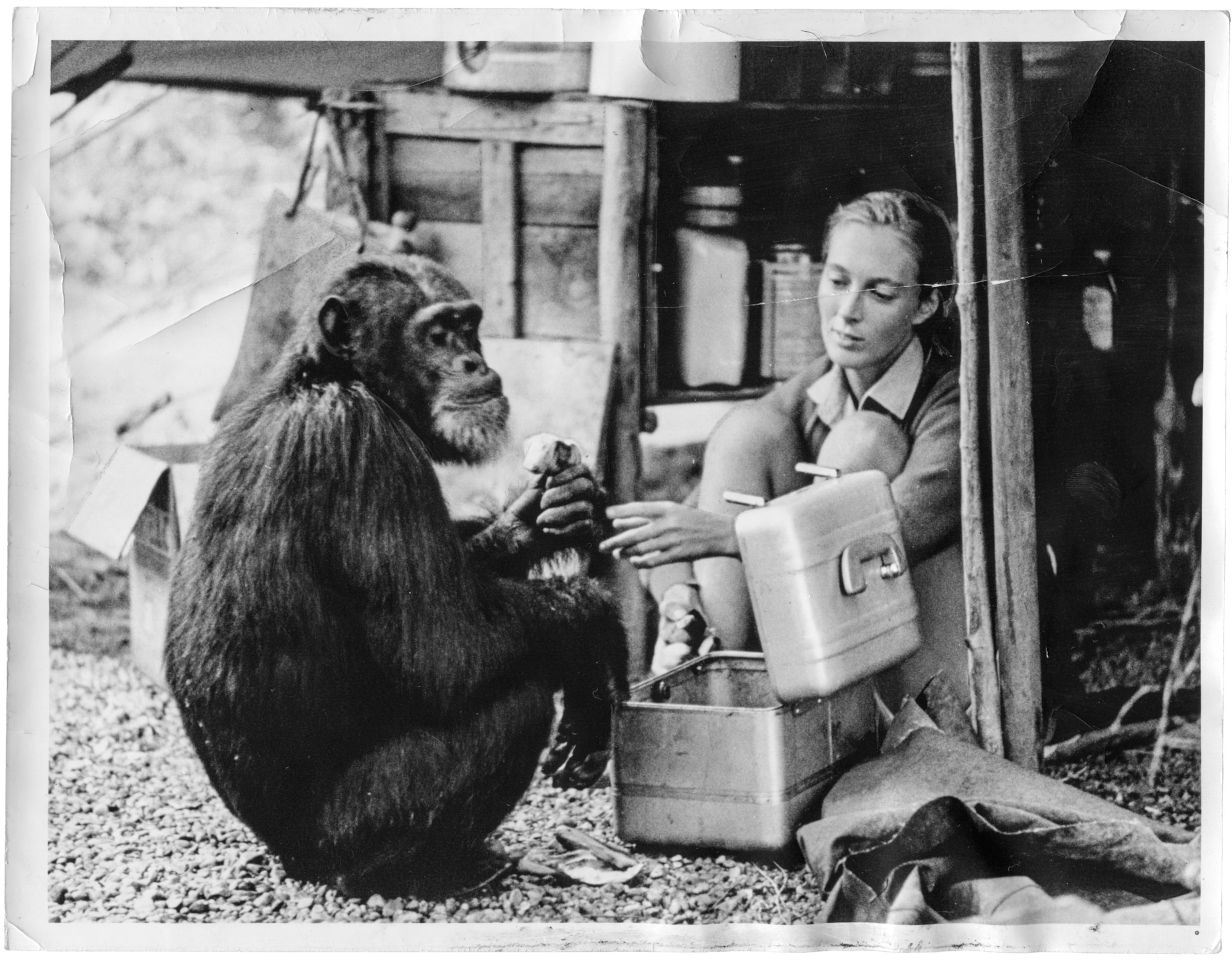

Her early fieldwork observing chimpanzees at Gombe Stream Game Reserve, in Tanganyika (now Tanzania), unveiled a rich catalog of shared behaviors—social as well as emotional—between humans and apes. She was “the woman who redefined man,” her biographer, Dale Peterson, wrote.

National Geographic's role in Goodall's rise

Goodall came to the attention of the National Geographic Society in 1961. Her mentor, paleoanthropologist and Society grantee Louis Leakey, told the Committee for Research and Exploration—the august group of 16 men handing out grants to scientists, explorers, and others—about his assistant at the Coryndon Museum in Nairobi, whom he’d sent to Gombe to observe chimpanzees.

(Jane Goodall’s original tale of chimpanzees still astonishes today.)

The relationship with the Society would span four decades, but initially at least, it was not a smooth ride. Though it approved $1,400 for Goodall’s work, the committee balked at Leakey’s request for money to underwrite her living expenses while she wrote up her findings. The men were wary. Jane Goodall was thin—frail-looking. She lacked scientific training. She had no degree. A lone woman in the wilds of East Africa studying chimpanzee behavior, vulnerable to violent weather, predatory animals, poisonous snakes, and malarial mosquitoes? To be asked to kick in 400 pounds (then $1,120) more might be pushing it.

Leakey cannily played his trump card: He told them that Goodall had documented the primates making and using tools—blades of grass and twigs lowered into mounds to fish for termites. Previously, only humans were thought to have the capacity to do that.

That got their attention. They approved the additional funds, propelling her work forward. It was arguably the best investment the National Geographic Society ever made. Its magazine and television coverage would introduce Jane Goodall, perhaps the best known woman in science, to the world.

“Comely Miss Spends Her Time Eyeing Apes” and “Eat Your Heart Out, Fay Wray,” the headlines proclaimed with a whiff of salaciousness. Even Society President Melville Bell Grosvenor would refer to her as “the blond British girl studying the apes.” She didn’t care. In fact, it was potentially useful; people would be less threatened by, and more likely to help, a woman. “I was the Geographic cover girl,” she said wryly.

The roots of Goodall's animal advocacy

The red brick Victorian where she grew up in the English seaside town of Bournemouth held a household of women: Jane; her mother, Vanne; sister, Judy; two aunts; and a grandmother. Her father, a British Army officer, was mostly absent and later divorced her mother. As a child, she yearned for adventure and to do the things that men did and women didn’t. Most imperatively, she longed to go to Africa to study animals. In that house of women, and particularly with the encouragement of her mother, she learned self-reliance and believed she could become anything she wanted.

(How Jane Goodall changed what we know about chimpanzees.)

The importance of nurturing would be affirmed when she got to Gombe and observed Flo, the matriarch of the first chimpanzee family she studied. Flo was loving and—most of all—attentive to and supportive of her children. Goodall’s own mother accompanied her (the research committee insisted on a chaperone) for her first five months in the bush. It was a dream fulfilled. “This was where I was meant to be,” she said in the 2020 National Geographic documentary Jane.

In the field and in the world at large, she left the lightest of footprints. In the forest, she often went barefoot. A vegetarian, she literally ate like a bird. She lived like a pauper, a colleague once remarked. The material was immaterial to her. It was all about her chimpanzees, the environment, conservation, ensuring that the world didn’t self-destruct.

Her earliest study subjects as a child had been the earthworms she put under her pillow until her mother pointed out they would die without soil, the robin she coaxed into building a nest in her bookshelves, and her beloved dog, Rusty, a mongrel. Rusty, her first teacher, taught her that intelligent animals had emotions as well as distinctive, individual personalities.

She saw that in David Greybeard, the first chimpanzee to approach and accept the “peculiar white ape,” as she referred to herself. There would be a clay model of him on her wedding cake when she married Hugo van Lawick, the photographer National Geographic sent out to document her work. David Greybeard was trusting, calm, determined. Goliath, the alpha male in his cohort, was tempestuous; Frodo, a bully. Later, when Goodall turned her fieldwork over to others to take on the mission of raising awareness and funds to make Earth a greener, more sustainable place, it was about the individual as well.

How Goodall redefined chimp behavior

She could hold a crowd in thrall—even entertainment-savvy Hollywood types—and make a rock star entrance. A crescendo of her pant-hoots would fill a room, increasing in volume: Ho hoo ho hoo HOO HOOO! Then, as the calls faded to silence, she would step from behind the curtain to a standing, stomping ovation. Her quiet passion would spill over the audience; tears would flow, and then, the checks.

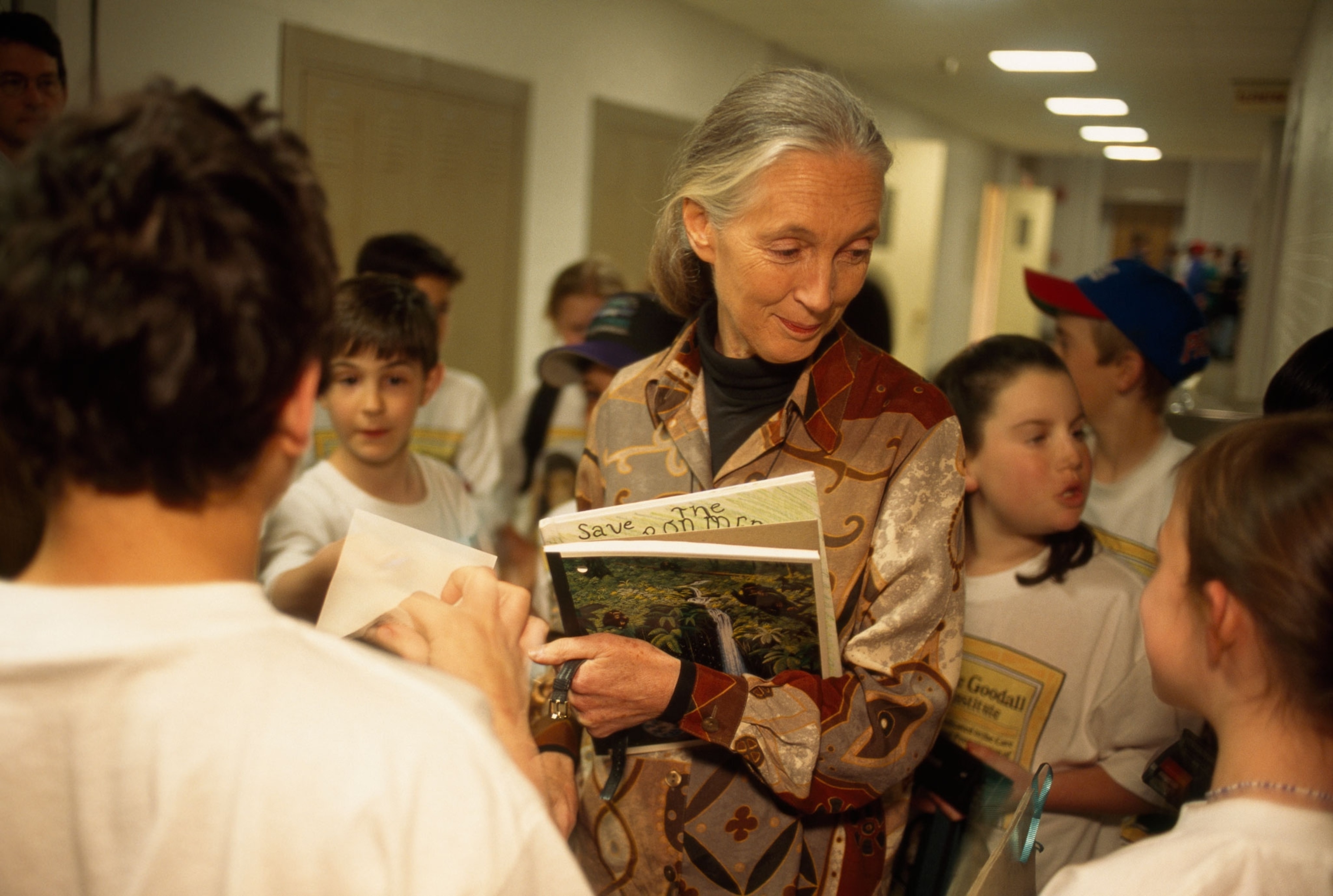

Once, at a signing event in a small-town bookstore, National Geographic photographer Nick Nichols asked why they weren’t in a larger venue like the auditoriums she often lectured in. He recalled: “She just looked at me and said, ‘But what if there is just one person who comes in today who changes things for the planet?’” Even the person seated next to her on a plane might be that individual.

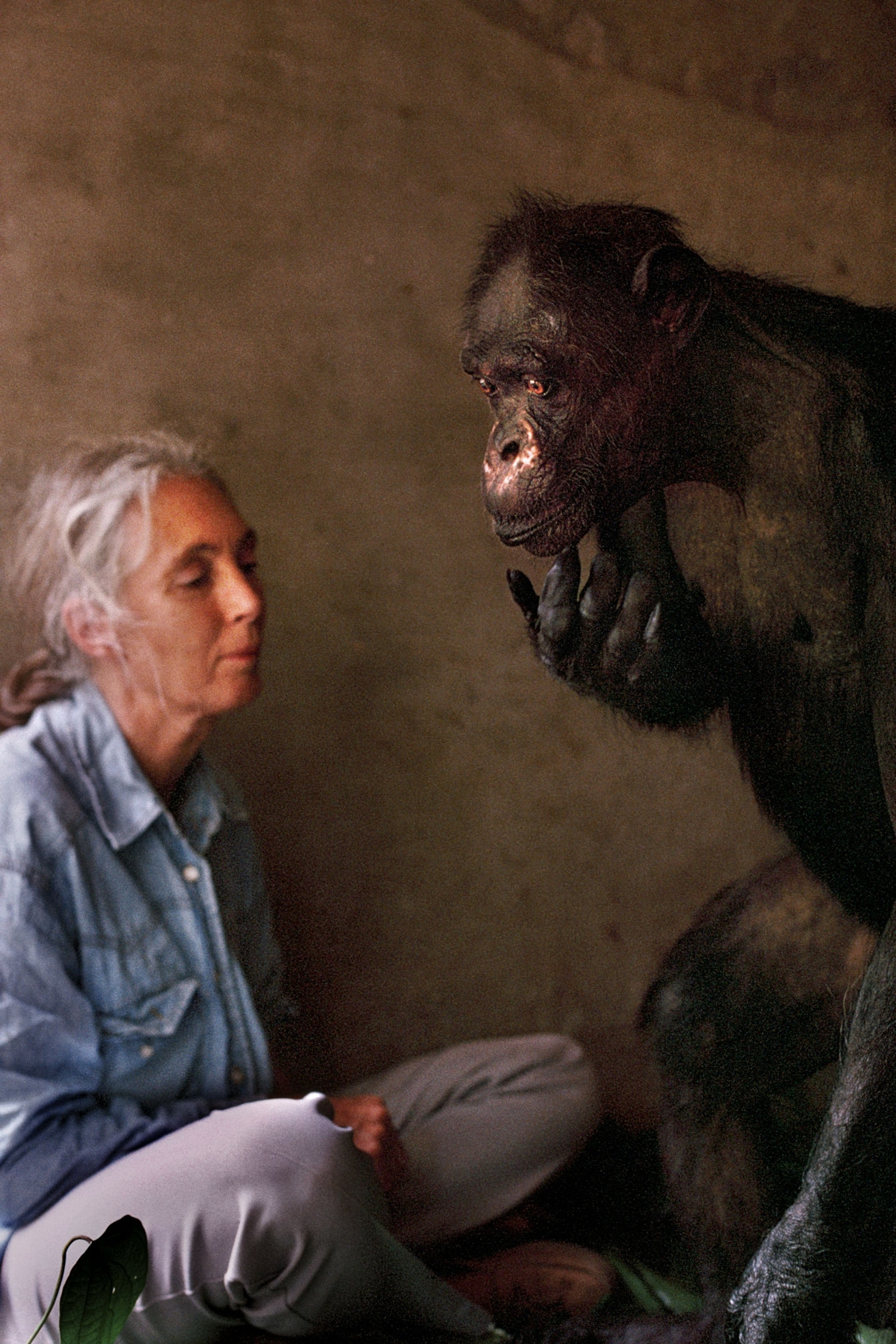

Goodall saw how a caged animal was turned into a diminished, demeaned version of itself that was reflected in its eyes and in the way it moved. It was her moral imperative to change that. “We should be kind to animals because it makes better humans of us all,” she told Mary Smith, the photo editor at the magazine who helped shepherd her stories into print. She influenced the National Institutes of Health to end the use of chimpanzees in medical research and enlisted Secretary of State James Baker in 1989 to help suppress the African wild meat trade.

In 1991, she formed the nonprofit Roots & Shoots, tapping into the enthusiasm of young people in her mission to stop environmental destruction, determined that the next generation would be better stewards of the world than the previous one. She could make allies of unlikely recruits. She persuaded Conoco Oil to build the Tchimpounga Chimpanzee Rehabilitation Center, in the Republic of the Congo, which opened as a sanctuary for orphaned chimpanzees in 1992.

There were awards: the French Legion of Honor. Dame Commander of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire. The Kyoto Prize. The Schweitzer Medal. Honorary degrees from universities in Europe, North America, South America, and Asia.

And there was a price. The invasion of microphones and cameras, “hungry,” David Quammen wrote in National Geographic, for her “every word and glance.” The press of worshipful fans, reaching out for a touch, a word, an autograph, as if for a holy relic. When she went on the road to preach the gospel of conservation—well into her 70s, she was still spending 300 days a year circling the globe—she might wake up wondering where she was, bleary with exhaustion. No matter. What counted was the mission.

When asked by an interviewer if she was a scientist first or a mystic, she opted for mystic. “I didn’t want to be a scientist,” she explained. It was Louis Leakey who pushed her into working for a degree, a Ph.D. from Cambridge University in animal behavior, because it helped indemnify her against the criticism of her peers who had, early in her research, derided her for not doing science properly.

Instead of assigning numbers to her subjects, she gave them names. She ascribed emotions to them. She anthropomorphized them. Goodall could do so because she had observed a young chimp, anguished by the loss of his mother, fall into depression and die. She saw a dark side as well: Males that bullied their way to the top. And when the cohort split into two warring factions: murder. “I thought they were like us but nicer. It took me a while to come to terms with the brutality,” she said.

It would infuriate the creationists, but her work suggested that perhaps it was not that apes mirrored human behavior, but that human behavior mirrored that of apes. “I felt I was learning about fellow beings capable of joy and sorrow … fear and jealousy,” she said of those years at Gombe.

And when ragged-eared, bulbous-nosed Flo—matriarch of the first family of chimpanzees she studied, who had taught her so much about nurturing—died, Jane Goodall cried, expressing an emotion shared with the chimpanzees she studied and loved: Grief.

Directed by Brett Morgen with music by composer Philip Glass, the feature documentary "Jane" uses never before seen footage to tell Goodall’s life story. Stream the film now on Disney+.