Inside the murky world of the aquarium trade

An eight-year undercover investigation has taken down poachers and smugglers raiding Florida’s coastal waters for corals and fish.

Miami, Florida — It was the grouper that got her. A 12-year-old speckled grouper with big bulbous eyes and a vacuum-strength pucker needed a new home because its owner had died, and Andrea Stockhausen agreed to take it.

That was 14 years ago. “I had no aquarium experience whatsoever,” Stockhausen said. “It was something new, something cool. I fixed up its tank and updated the filtration and lighting—and then I was hooked.”

Like any new collector, Stockhausen, then 45 and a satellite communications specialist in Fort Lauderdale, Florida, immediately felt compelled to buy more fish. But there was a problem: The grouper was nearly a foot long, with a voracious appetite.

“I sat in front of the tank and thought, I can’t put anything else in there—he’ll eat it,” she said, laughing. She was going to need another tank—and soon another, and then another. Within 16 months of adopting her grouper in 2004, Stockhausen had upgraded from a 50-gallon saltwater tank to a 90-gallon tank to a 180-gallon tank to a giant 250-gallon acrylic case as big as a horse set center stage in her living room. With dark wood trim and a decorated interior, it was filled with dozens of flashy inhabitants, including a brilliant yellow tang, fluorescent royal grammas, cute little striped clownfish, live anemones, and mushroom corals.

She constantly thought about how to grow her collection. “One weekend I would go to all the fish stores north of me,” she said, “and the next I’d go to all the fish stores south of me.”

After befriending some commercial divers collecting wild tropical fish in the Florida Keys, she had an epiphany: “I can do this for a living,” she said, beneath the blue glow of UV lights illuminating hundreds of soft corals in psychedelic shades and patterns at her wholesale business, Exotic Sealife International, in Miami.

When Stockhausen opened the company, in 2006, she tapped into a multimillion-dollar a year global business supplying aquariums ranging from tiny tanks in dorm rooms to giant displays like the 1.2-million-gallon Open Sea exhibit at California’s Monterey Bay Aquarium.

More than 20 million marine fish from about 45 countries are imported each year for the worldwide aquarium trade. In the United States, which accounts for roughly half of those—more than any other country—an estimated 2.5 million households own saltwater fish.

Nearly 3,000 saltwater species, including fish and invertebrates, displayed in tanks are captured from the wild, predominantly in Indonesia and the Philippines, where harmful chemicals such as cyanide are sometimes used illegally to stun the animals for easy collecting. No one knows exactly how many marine animals are sold on the black market, but some experts estimate that 10 to 30 percent of marine animals in stores have been caught illegally with cyanide.

Only a small percentage of additional commercially available marine fish are captive bred, mostly variations of popular clownfish, gobies, dottybacks, blennies, and certain corals. That’s partly because large-scale aquaculture requires costly facilities giving round-the-clock care to hundreds of thousands of animals with very specific needs.

Operation Rock Bottom is one of the biggest law enforcement attempts to crack down on illegal marine-life crime in the nation’s history.

Stockhausen, who has a reputation for ethical standards and practices, is one of a few licensed wholesalers in the Miami area. She ships marine life collected from all over the country and around the globe to as far away as Germany, Japan, Russia, and South Africa. On this particular day, she was preparing 60 yellow tangs—hand-caught with nets from a reef off Hawaii’s Big Island, flown from Kona to Los Angeles, Los Angeles to Miami, quarantined for five days at her shop, and then packed in plastic bags and boxes—to be flown by Aeroflot to Moscow, where they’d be sold in fish stores.

Concerns about the overcollection of many fish species arise from the fact that the aquarium trade is largely untraceable. No centralized global database exists for tracking how many fish are scooped from reefs—or even how they’re captured. In places where cyanide is used, the toxin not only damages fragile coral reef ecosystems but also propels the demand for fish because poisoned animals are prone to go belly up sooner, say experts like Andy Bruckner, research coordinator at the Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary, who has studied reef ecosystems all over the world.

“They’ll survive for about six months, but then they have organ damage and die, and people think it’s something they did,” he said. “It’s possible to have a sustainable fishery,” he continued, “but it really depends on the volume of marine species you’re collecting and how you’re collecting them.”

Florida, with a chain of small islands and colorful coral reefs arching nearly 120 miles from the southernmost part of Miami to Key West has established a ban on new commercial saltwater fishing licenses for collecting, selling, and dealing in marine life.

The only way to join the fishery legally is to purchase an existing permit, and the scarcity of those makes them extremely valuable—as much as $35,000, fishermen say. To help keep the fishery sustainable, the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission, which manages and regulates the state’s fish and wildlife resources, maintains limits on how many animals can be collected in a day and on the range of allowable sizes. For example, it’s against the law to collect certain colorful angelfish measuring less than one and a half inches or more than eight inches. The state also manages controlled fishing areas and has a trip-ticket system that requires fishermen to report everything they catch.

People who participate in the Florida aquarium fishery and collaborate closely with the state herald their internal monitoring system as the gold standard for ornamental fisheries around the world.

OPERATION ROCK BOTTOM

Federal law enforcement agencies see things differently. They say South Florida’s marine life industry touts itself as being self-regulated when in fact some people use loopholes in the laws to illegally collect, launder, and traffic aquarium species.

Amid signs that the region was becoming a hot spot for the illegal aquarium trade, in 2010 the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration launched a lengthy, and ongoing, special investigation named Operation Rock Bottom. It’s one of the biggest law enforcement attempts to crack down on illegal marine-life crime in the nation’s history.

“In eight years, the investigation has spanned the whole industry—from collectors and wholesalers to retailers and public aquariums,” said David Pharo, the Fish and Wildlife Service agent in charge of the operation. “The quantity of wildlife being illegally harvested was creating tremendous impacts to the marine life [ecosystem], as well as creating such a competitive market that legal marine-life collectors could not sustain their business and make an honest living without poaching.”

Members of the Florida Marine Life Association, a trade group, strongly object to the notion that their industry has been plagued by widespread illegal activity and challenge claims that collecting harms coral reefs.

Jeff Turner is a custom aquarium builder and the organization’s president. “We have a limited-entry fishery. If there are a few bad apples on the tree, then they need to go,” he said. “There’s a lot of pressure on coral reefs from many, many things, but they have nothing to do with the fish business. Tropical fish collecting is just a hell of an easy target. It’s sexy, colorful, and it sounds bad.”

Tom Watts-FitzGerald runs the environmental crimes division of the U.S. Attorney’s Office, Southern District of Florida, and he’s been the lead prosecutor working closely with Rock Bottom investigators since the operation began. Local intelligence has been key, he said.

“It all started with a fisherman who said he wanted to talk. This old crusty conch, a major violator of wildlife laws, had found religion after going to some of his best coral collection sites and finding a moonscape.” (“Conch” is the common name for a longtime resident of the Keys.) “The reef that had thrived for years was completely barren. It suddenly hit him that he, and the people like him, had played a role in that, and he steered us in the right direction.”

The fisherman was a collector of Ricordea florida, a soft coral that grows on submerged rocky substrates known as “live rock” in the Atlantic Ocean and Caribbean Sea and the Gulf of Mexico. Ricordea—found in a brilliant array of colors, from greens and purples to blues and yellows—and chunks of live rock are highly sought after for aquariums largely because of a shift in the types of tanks people keep. Gone are the days when hobbyists built fish-only aquariums. Today’s aquarists are constructing miniature replicas of reef ecosystems, with live corals, fish, invertebrates, and plants, a trend that has created a market for species previously ignored.

Early in the Rock Bottom investigation, government agents began monitoring Ricordea collectors. Soon they homed in on a business named Key Marine Inc., located on Grassy Key, about 55 miles north of Key West. By March 2011, they had enough evidence to raid the place and charged Eric Pedersen and Serdar Ercan, company vice president and secretary respectively, with poaching and smuggling large quantities of Ricordea, live rock, ornamental fish, sea fans, and several species of sharks from the Florida Keys to wholesalers throughout the U.S. and abroad.

“The motivation was money, money, money, and greed,” Pharo said. “They were only allowed to collect a hundred quarter-size polyps of Ricordea a day, but on some days they were collecting more than a thousand. Or they’d just whack off huge chunks of rock—from golf ball and softball sizes to as big as a basketball and even a large cooler—covered with hundreds of polyps, because it was more efficient than taking them one by one. If you’re poaching, you don’t want to be there long—you have to get in and get out quick.”

Clues from the surveillance operations, along with documents and equipment seized in the raid, indicated that Pedersen and Ercan were squarely at the center of multiple crime schemes spread throughout Florida and in several other states.

Facing the threat of up to five years in prison for conspiracy charges and wildlife crimes and tens of thousands of dollars in fines, Pedersen agreed to cut a deal, according to Watts-FitzGerald, perhaps in hopes of a lighter sentence: He would work as an informant and wear a wire to help the agents bust people and businesses he’d been dealing with.

TRAIL OF CORRUPTION

Tropicorium, a reef aquarium store in Romulus, Michigan, was on the fish and wildlife agents’ list of suspected corrupt companies. Owner Richard Perrin had been making regular diving trips to the Keys for years to collect items to sell in his shop, Pharo said. While in town he would store the bounty at Pedersen’s place. But the collecting expeditions were becoming strenuous for a man approaching 80.

In May 2011, Perrin brought an employee named Joseph Franko, in his young 30s, along for the ride. According to court documents, they had an extremely productive trip. In just one day, the pair collected roughly 60 corals, including more than 20 protected sea fans, and FedExed them back to Michigan. Then they packed their Chevy van with the remaining haul and began the 1,500-mile journey home. A quick pit stop along the road in Big Cypress National Preserve gave Franko a chance to poach a few protected baby alligators while Perrin kept watch for police, Pharo said.

About three months later, Perrin and Franko returned to the Keys to restock their inventory with anemones, angelfish, sea fans, and other species, including a few more baby gators, court records show. After they returned to Michigan, federal agents posing as shoppers closed in on the business and made several undercover buys to confirm that Tropicorium was selling the illicit marine life.

Perrin and Franko were indicted in September 2013 for conspiring to illegally purchase, harvest, and transport marine life and reptiles from Florida to Michigan to sell at Tropicorium. Perrin cooperated with the investigation, according to court records. In late March 2014, he received a sentence of three years’ probation, a $15,000 fine, and the forfeiture of his Chevy used for transporting illegal wildlife. Franko got five months in prison followed by five months’ home confinement.

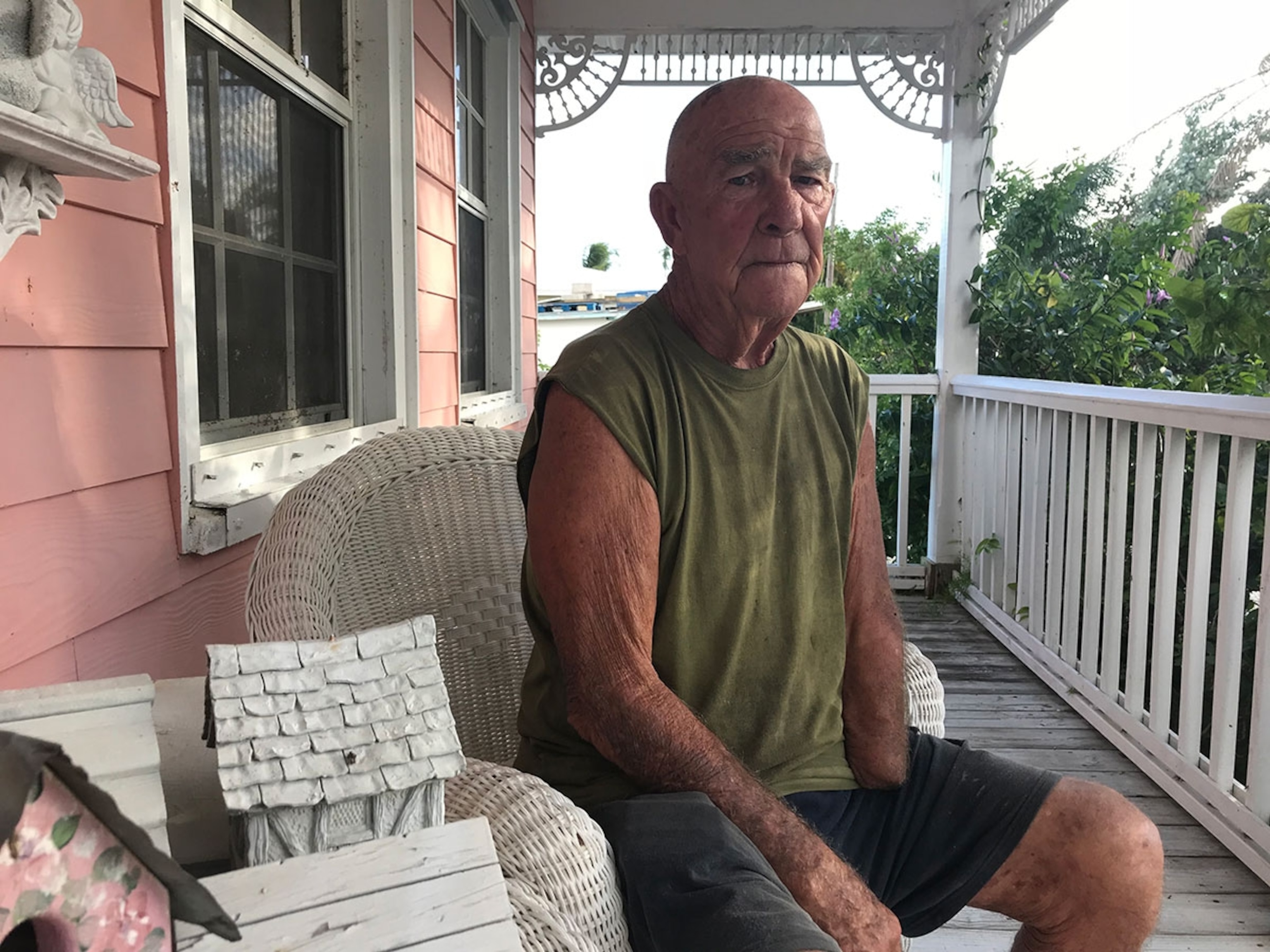

Another close Pedersen associate, Charles “Jamie” Jamison, is a fisherman in his 70s who’s known by some in his community as the “one-armed coconut telegraph.” That’s because he cut off his hand when it got caught in a winch on a lobster boat, and he lives in the so-called Coconut Republic of the Keys, and he talks a lot.

Jamison’s penchant for telling fish tales provided ample opportunities for Pedersen to secretly record their conversations about the various marine life Jamison was catching, including some bonnethead sharks to sell to a couple, Leah and Phillip Gould, who run an aquarium supply company on nearby Big Pine Key. The bonnethead is a member of the hammerhead family that grows to about four and a half feet long and is abundant along Florida’s shores. Anglers holding a Florida saltwater fishing license can catch up to two sharks a day, but collectors catching the sharks for the aquarium trade are required to have commercial saltwater fishing licenses.

Jamison admitted in a plea agreement that he was catching sharks without a license. The Goulds, in turn, were buying the sharks even though they were supposed to have made sure Jamison’s paperwork was in order, court documents show, and they were selling the sharks out of state, in violation of U.S. smuggling laws.

Judges don’t often sign “black bag warrants,” an old-time term for authorizing law enforcement agents to surreptitiously enter a suspect’s premises at anytime of day or night without notification, said U.S. attorney Tom Watts-FitzGerald. But agents made a convincing case that if Jamison knew they were coming, he might toss the sharks into the bay.

At 2 a.m. one stormy night, a team of Fish and Wildlife Service agents executed the warrant to sneak onto Jamison’s property. They climbed into the shark tanks to catch and tag the animals with tiny internal trackers bearing serial numbers that could be identified with an electronic reader, much like the ID chips used to recognize pets if they get lost.

The Goulds had an order from the St. Louis Zoo for four bonnethead sharks, and they arranged to fill the order with animals caught by Jamison, said the Fish and Wildlife Service’s Dave Pharo. When Phillip Gould left the Keys on August 21, 2012, in a rental truck with two removable holding tanks containing the sharks, Pharo was on his tail.

“He pulled into the Raceway gas station in Florida City, just north of the Keys, to check on the sharks, and in an undercover capacity, I was invited onto the vehicle to look at them,” Pharo said. When Gould arrived in Missouri, the service’s agents there confirmed the arrival of the sharks that had been transported.

During the course of the next few years, Pedersen, Ercan, Jamison, and the Goulds were all sentenced. Pedersen, who didn’t respond to requests to be interviewed, was dealt the heaviest punishment—two years in prison and a $10,000 fine. Ercan received one year and a $6,000 fine; Jamison paid $2,000; the Goulds, $5,000 each. Everyone got between 18 months’ and five years’ probation. Although Pedersen and Ercan may have been the bigger offenders, Pharo said, “the Goulds and Jamison were in cahoots catching and selling those sharks illegally.”

Jamison lives in a waterside cottage on Little Torch Key, roughly 30 miles north of Key West. Sitting on a wicker chair on his front porch one October afternoon, he rested the stump of his left arm on his leg and told his version of the story.

“Pedersen was protecting his ass because he’d been nailed,” he said. “Sure, I was selling bonnethead sharks to the Goulds—but those sharks aren’t endangered. I can catch two a day, kill them on my dock, and feed them to my cat,” Jamison continued. “The only reason I was breaking the law was because I didn’t renew my permit. If I’d done that, this whole rigmarole wouldn’t have happened. With the lawyer’s fees, it probably cost me $20,000, and now I’m a felon.”

Jamison walked across the driveway to his office in a small garage and sat down at a desk where he keeps a large calendar, a calculator and a clock, along with a dirty ashtray stacked atop a pack of Marlboros.

“I have nothing to hide,” he said, reaching into a drawer to retrieve a plastic baby- wipes box that he uses for storing trip tickets. “Look, it’s all here,” he said. “I’ve always been honest with my paperwork. Pederson screwed me over. I didn’t feel sorry when he went away, because what he was doing was strictly illegal. Then you gotta suffer the consequences.”

It was damn good to see some of these guys get in trouble, damn good.Jeff Turner, Florida Marine Life Association

As the Rock Bottom investigation unfolded, businesses linked to Key Marine continued to fall. In Miami, D.R. Imports owner Robert Kelton, known in the fishing community as “Fat Bob,” and general manager Bruce Brande were indicted in 2014 on charges that they conspired with different marine dealers throughout the Keys to buy illicit live rock and Ricordea collected from the Florida Keys Marine Sanctuary.

Kelton and Brande were effectively laundering marine life, Pharo said, covering their tracks by using fraudulent paperwork to disguise the marine organisms as being legally imported from Haiti. Records seized by agents showed that the businessmen raked in tens of thousands of dollars buying and selling black market marine organisms taken from the Florida Keys.

Some fishermen suspect Kelton was cooperating with federal agents, as Pedersen had done, possibly to receive a lighter sentence. Pharo wouldn’t comment about that claim. The judge handed Kelton two years in jail. Brande got one.

ALL IN THE FAMILY

All told, agents say Operation Rock Bottom has caught roughly 20 people, from Florida to as far away as California, Colorado, New York, and Idaho.

A November 2012 indictment tells the story of an alleged conspiracy involving Ammon Covino, then the president of the Idaho Aquarium, in Boise, and its secretary, Christopher Conk, who were charged with buying lemon sharks and spotted eagle rays poached from the Keys to display at their facility. Both species are listed as “near threatened” by the International Union for Conservation of Nature, which monitors the status of animals and plants, and those who catch them in the wild are required by law to have special permits.

Covino had been looking to buy some spotted eagle rays. A seller, working as an informant, quoted him a price of $1,250 per ray, according to the indictment. But the seller said it would take time to secure the permits. A few weeks later, he told Covino that he couldn’t get them. The indictment states that Covino suggested the seller might “sneak” the rays to him and quotes Covino saying, “Just start doing it…who gives a s***, man?” Credit card records show that on May 7, 2012, Covino paid $3,750 for three illegal rays.

About a month later, Conk called to say that he and Covino were looking for some lemon sharks. Since it was illegal to catch lemon sharks, he said the transaction would have to be kept “on the down low,” according to the indictment. The sharks were loaded on a flight to Boise, where Conk was waiting to collect them in his pickup truck.

Covino and Conk were arrested on February 21, 2013, on conspiracy and wildlife-trafficking charges. Court documents show that later that evening, after Covino was released on a $100,000 secured bond, his 20-year-old nephew, Pete Covino, phoned the marine dealer saying he was calling on behalf of Ammon to cancel a scheduled shipment, and he requested that the seller refund Covino’s credit card. Ten minutes later, Pete called back to add that if he had any questions, he should Google Ammon Covino, and “it would tell him everything he needed to know,” and “if you could erase all the e-mail and text messages from him too, that would be great.”

Pete spent two months in prison for trying to destroy and conceal evidence in a legal case. Covino received a year in jail for his offenses. Conk, who cooperated with investigators, according to prosecutors, served a shortened sentence of four months.

But Ammon Covino didn’t stay out of trouble long. In February 2016, he was sentenced to an additional three months and fined $50,000 after agents caught him working with his brother, Vince, then the owner of the San Antonio Aquarium, in Texas, in violation of the conditions of his release: no employment in the aquarium business. Then, in November 2016, authorities issued another warrant for his arrest when, again disregarding court instructions, he was preparing to open two new aquariums, in Nevada and Utah. That put him back in prison in for another eight months.

Reached by phone, Ammon Covino said the charges brought against him were “bogus.”

“This fisherman we’d been working with for years purposely went out and caught animals without his license and then sold them to us, and then got us caught up in this ridiculous law that says if you buy an animal captured illegally, it’s a felony,” he said. “I wasn’t doing anything wrong. And yet I spent 23 months in maximum-security prisons. One of them was Beaumont, Texas—they call it ‘bloody Beaumont.’”

Covino said that he has a lawyer working on suing the government, alleging wrongful imprisonment. “I never broke probation stipulations,” he said.

Fish are a family business for the Covinos. Vince owns a company called Seaquest Aquariums, an interactive marine life attraction featuring touch tanks and birthday parties at shopping malls. The company has locations in Layton, Utah; Fort Worth, Texas; Las Vegas, Nevada; and Littleton, Colorado. It has plans to open new facilities in Fort Lauderdale, Florida, and Folsom, California.

Previous Covino-operated aquariums have been shuttered or transferred to new ownership amid public concerns about suffering animals and the family’s criminal history. Covino claims he’s never even worked for Seaquest. “I only provide advice to my brother when I visit his facilities,” he said. “I’m in charge of operations at the Austin and San Antonio Aquariums, owned by my wife.”

In a twist of irony, that San Antonio Aquarium got hit earlier this year by three burglars who stole a shark and rolled it out of the building in a baby carriage, providing amusing headlines and lots of tweets and Facebook shares.

Meanwhile, public campaigns to put Seaquest out of business have been pumping out press releases. In Fort Lauderdale, animal welfare activists are staging weekly protests at the site where Seaquest is trying to build a new aquarium in the city mall. They’re petitioning local government to prevent construction on grounds that the building won’t be able to support the weight of both an existing gym and an aquarium with thousands of gallons of water.

“They build first and ask for permits afterward—that’s their MO,” said Ana Campos, a local private investigator and animal rights activist. “Their tanks are dirty, and animals are overcrowded. In Portland, an employee kept a ‘death log’ of hundreds of animals that died.”

Despite the bad press, Seaquest continues to eye new sites, in places including in Connecticut, New Jersey, and the Westfield Sunrise Mall, in Oyster Bay, New York, where hometown hero actor Alec Baldwin recently joined animal welfare activists voicing concerns. In an October letter from Baldwin and the People for Ethical Treatment of Animals to the town supervisor and board, the actor wrote, “Please do not allow this awful operation in town. The owner of this sleazy chain, Vince Covino, has not only flouted the law nearly everywhere he goes but also left untold animals suffering in his wake.”

Vince Covino declined to be interviewed for this story, but Seaquest marketing coordinator Erin Taylor supplied a statement in reply to Baldwin’s letter: “Seaquest successfully operates four interactive facilities at retail centers across the U.S. and we continue to grow. With a firm commitment to animal welfare and conservation, we adhere to strict guidelines of care with dedicated marine and husbandry teams along with a veterinarian supervising the husbandry staff at each location.”

TANKED

At press time, Campos was working on a strategic plan to urge more animal activists to rise up against Seaquest. Operation Rock Bottom investigators were “as busy as ever,” according to Pharo, though he couldn’t talk about active cases. And the Florida Marine Life Association was playing defense against the threat of media exposure.

“I don’t know why these people do these stupid things,” aquarium builder Jeff Turner said, expressing frustration about lawbreakers who give marine life collectors a bad name. “It was damn good to see some of these guys get in trouble, damn good. From my vantage point, that criminal investigation was a beneficial purging of the unscrupulous people,” he continued. “However, some good people have also been caught mainly due to infractions associated with their fisheries permits.”

Turner, who designs aquariums for the rich and famous as well as the Smithsonian Natural History Museum, in Washington, D.C., is a big believer that one day it won’t be necessary to collect marine life from the wild.

“This is the future,” he said, standing inside one of 16 Quonset huts owned by Oceans, Reefs, and Aquariums, in Fort Pierce, Florida. It’s the largest marine life aquaculture facility in North America, supplying hundreds of thousands of captive-raised fish and corals to nationwide pet stores, including Petco.

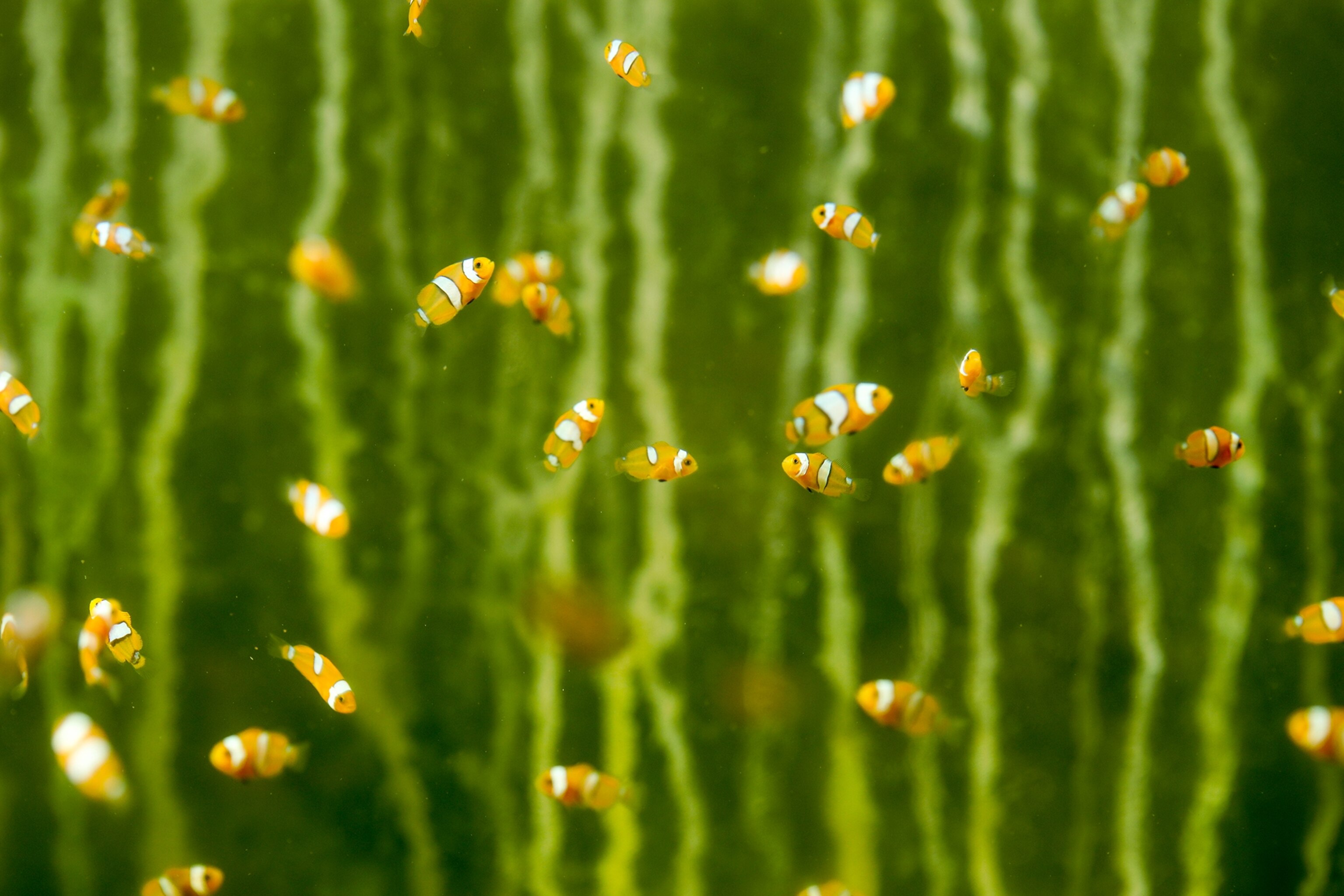

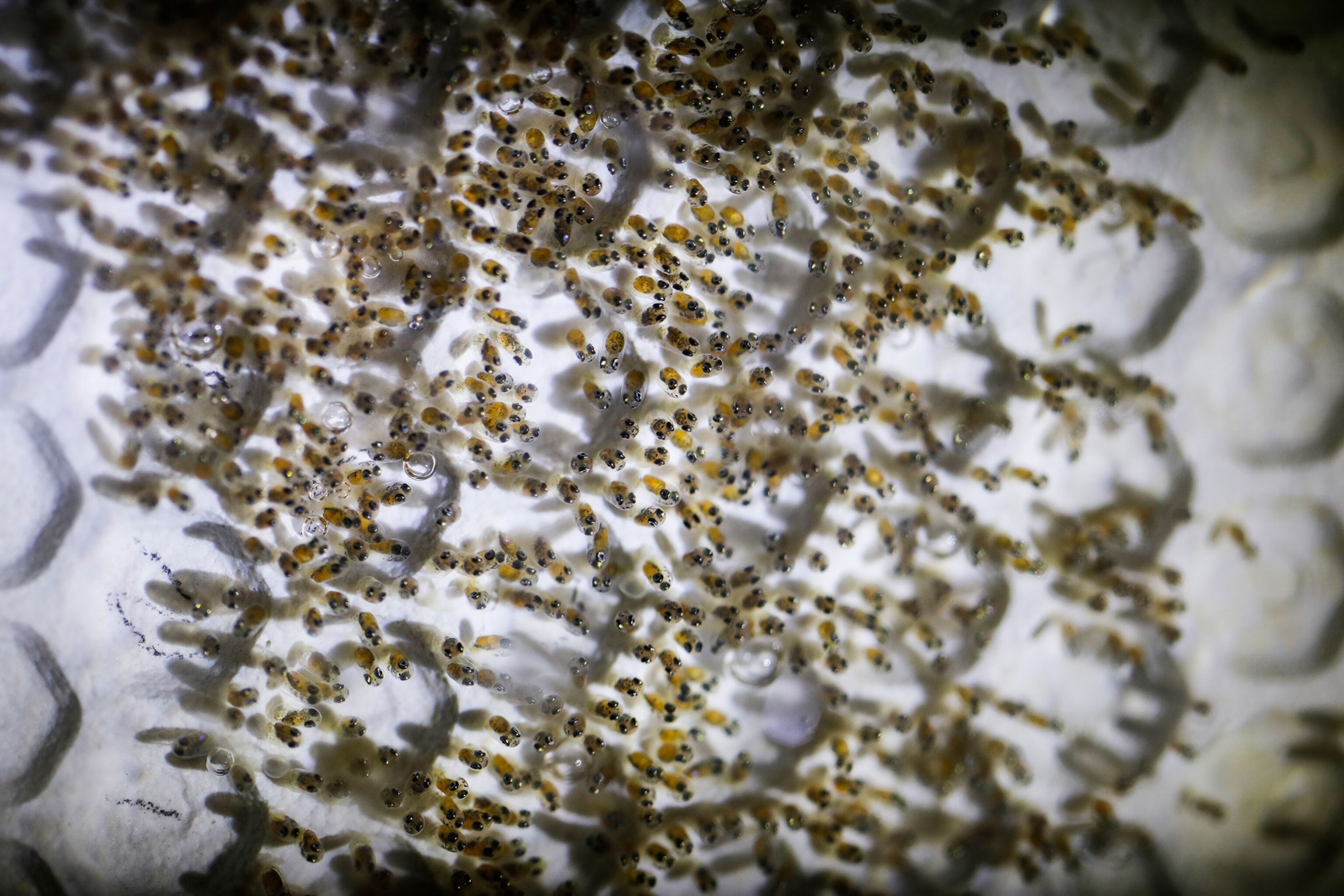

Fish tanks and huge tubs of gurgling water were stocked with clownfish in varied sizes and colors, from tiny eggs to full-grown Nemos. “That’s the first designer clownfish,” tour leader and company president Dustin Dorton said, pointing to one of the tanks. “It’s naked—no stripes. We bred the stripes out by collecting the fish with the least stripes from each spawn—it’s just like breeding dogs. Captive breeding has been so successful there’s no reason to import live-caught clownfish anymore.”

While aquaculture still represents only about 2 percent of the diversity on the market, Dorton said he expects that will grow. His focus has been on the mass production of top-selling fish in highest demand. “Clownfish sell for two to four dollars, but we can produce them by the thousands,” he said, “and I think that has a better environmental benefit. Your average hobbyist isn’t going to start an aquarium with a $2,000 angelfish. They’re going to start with a four-dollar damselfish.”

When the tour was over, Turner climbed back into his truck to drive south to his business in Fort Lauderdale, where 20-mile-an-hour winds had docked the boats that take tourists to snorkel and scuba dive on the reef. “There’s no diving today—no way, it’s too dirty, too much wind, too much waves,” Turner said. “That’s why aquariums are the best education tool for the ocean, because you can look at them 24 hours a day, 365 days per year.”

True, plenty of landlubbers have discovered a love of the ocean from viewing fish through glass. Perhaps in time, advances in aquaculture will aid the industry in becoming more environmentally sensitive and sustainable. But it will forever be easier and cheaper to pluck marine life from the sea. Left unchecked and untraceable, the demand for fish, legal or not, will continue to grow. Because that’s the thing about obsession: a collector always wants more.