In the ocean's 'twilight zone,' divers risk their lives in search of mysteries

For deep reef divers, descending into the ocean’s mesophotic layer can feel like exploring the moon. Discovering never-before-seen marine species is part of the mission.

Agat Bay, Guam — The sun shimmers across the glassy surface of Blue Hole, a heart-shaped underwater sinkhole, as two divers prepare to descend into its treacherous, turquoise abyss.

Sounds of buckles clicking, straps tightening, and gases swishing through tubes and tanks fill the tiny boat they’re aboard. The divers—Luiz Rocha, a National Geographic Explorer and an ichthyologist and marine biologist from the California Academy of Sciences, and Mauritius Bell, the academy’s dive safety officer—are gearing up to head 330 feet below the surface, far beyond the reach of most scuba divers.

In this part of the ocean, known as the mesophotic or upper “twilight zone,” sunlight is scarce and mysteries abound. Coral reefs thrive in the darkness, harboring life that often appears otherworldly.

Entering the twilight zone “feels like landing on the moon,” says Rocha, who has dedicated his career to studying fish and coral reefs there. “More often than not, one of the first things we see is a species that is unknown to science.”

For these “aquanauts” the mission is clear: retrieve three autonomous reef monitoring structures, or ARMS, that they placed at the bottom of Blue Hole eight years prior. The structures act as artificial reefs collecting marine life from a zone that is too deep for conventional scuba divers and too shallow to attract submersibles or remotely operated vehicles. As a result, this area remains largely unexplored and seldom sampled. Rocha hopes the ARMS will offer rare insight into life at these depths. And though he has made this plunge before, that doesn’t make the day’s dive any less dangerous.

(These creatures of the 'twilight zone' are vital to our oceans)

To get to the twilight zone, Rocha is relying on a device known as a rebreather. Unlike regular scuba diving systems, which supply divers with a set amount of breathable air that they exhale in streams of bubbles, rebreathers recycle the air that a diver exhales. That allows a diver to go deeper and stay longer, but it comes with increased risks. A malfunction can skew the mix of gases—too little oxygen, too much oxygen, or too much carbon dioxide—any of which would incapacitate a diver.

If anything goes wrong at depth, divers can’t rush to the surface for rescue: a rapid ascent can flood their blood vessels with nitrogen bubbles, triggering decompression sickness, a painful and life-threatening condition. Rebreather diving is considered five to ten times more dangerous per dive than conventional scuba diving, with estimates suggesting it claims around 20 to 25 lives worldwide every year.

“I think Luiz is crazy for doing this,” says Susanne Bähr, a postdoctoral researcher at Cal Academy who is aboard the expedition. But to Rocha, such dangers are well worth the tantalizing treasures that await him below.

“I’ve wanted to be an explorer ever since I was a kid,” he says, “and there's nothing better for an explorer than going to a place that nobody has ever been, finding a species that nobody has ever seen before.”

Only a few dozen scientists have the necessary training to venture into the mesophotic, between about 130 and 490 feet deep. Only a fraction of them have ever reached its deeper portions. The journey requires immense practice, can be extremely dangerous, and isn’t comfortable by any means.

With the last strap secured, Rocha takes a deep breath from his rebreather mouthpiece. “Seventy-five percent helium!” he squeaks, his voice high-pitched like a cartoon character.

At the depths he’s going, air becomes toxic. His rebreather feeds him a special combination of gases, the most abundant of which is helium. This cocktail prevents nitrogen and other gases from reaching lethal levels in a diver’s blood, but it cannot support them at great depths for long.

Though it will take Rocha less than 10 minutes to reach the destination, once he is down there, he will have only about 15 minutes to work before he has to start a slow and controlled ascent to the surface—a process that can take four to five hours.

Despite the hazards ahead, Rocha was eager to begin. On the boat, Bell rattled through the final questions on their safety checklist:

“Are you mentally and physically prepared to dive?” Bell asks.

“Yes!” Rocha replies.

After one last gear check and review of emergency protocols, they hop in the water.

ARMS on coral reefs

Scientists once thought that the deeper one dove, the drabber and more lifeless a reef would become. But over the past few decades, they’ve learned that reefs in the twilight zone are wildly biodiverse and harbor colorful creatures.

Although scientists have significantly increased their understanding of these mysterious ecosystems over the past few decades, “our knowledge of deep reefs is still in its infancy,” says Carole Baldwin, the curator of fishes at the Smithsonian's National Museum of Natural History. “Most places still have not been explored.”

For over a decade, scientists have been attempting to bridge this gap by placing ARMS on deep reefs around the world. Used and deployed widely by researchers at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), ARMS are stacks of plates, about one cubic foot in size, that mimic the complex structure of the seafloor.

(Why this deep-sea explorer thinks diversity is so important for science)

If coral reefs are underwater cities, then ARMS are apartment buildings offering free rent. Vacant real estate is hard to come by on coral reefs, so when an ARMS shows up, corals, sponges, worms, anemones, and other organisms waste no time moving in. Eventually, everything from fish to crabs will set up shop. The longer an ARMS sits on a reef, the more local critters make use of it.

In 2018, Rocha and his team placed four ARMS in Blue Hole and several more on Guam's other deep reefs and in the shallows. Studying the reef this way is more efficient than going down there and collecting individual specimens by hand, Rocha says.

“Instead of sampling for five minutes,” he says, “we're sampling for eight years.”

After retrieving the ARMS, Rocha places them in sealed containers supported by a small float. Now he and Bell begin their hours-long ascent. They pass the time by taking photos, playing rock-paper-scissors, and briefly slipping off their mouthpieces to slurp on applesauce pouches.

A few hours after the pair disappeared into Blue Hole’s cavernous maw, a second team of divers sets off to rendezvous with them. The two teams meet at around 100 feet, where Rocha and Bell hand off the ARMS to the second team to bring up to the surface. With the ARMS safely secured, the second team hauls the structures on board and puts them in bins filled with seawater—then the scientists gathered around, eager to get a glimpse of their biological bounty.

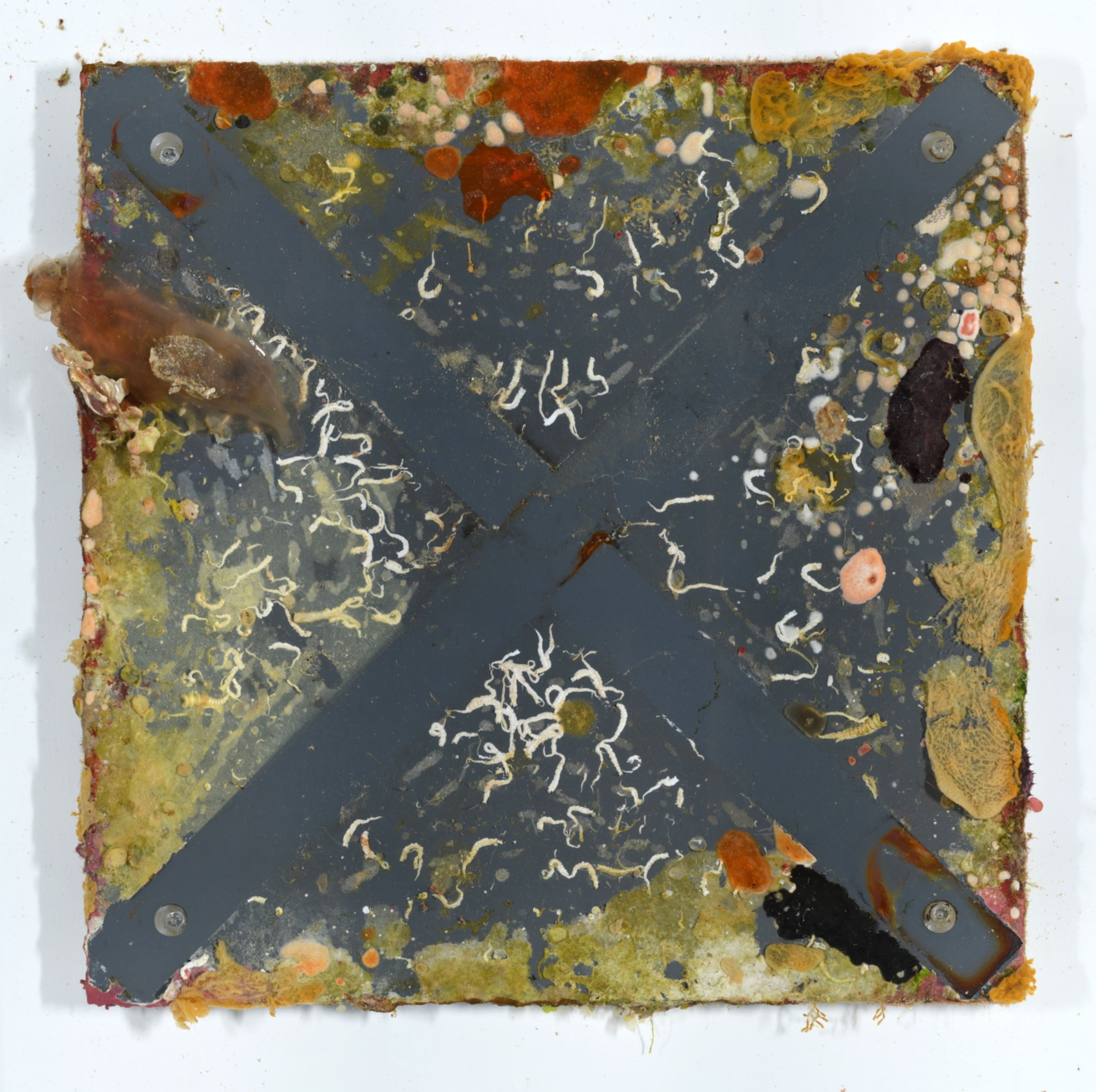

‘Wows’ erupted from every scientist aboard as they removed the first ARMS from its container. Each plate looked like the work of an abstract artist; their surfaces decorated with bulbous orange sponges, winding white worm casings, and ruby red tunicates. On its edges hang branching corals as big as the ARMS’s plates. Hot pink fish no bigger than a paper clip darted through the bin’s murky water, experiencing direct sunlight for the first time.

Sunken treasure

The researchers rush the ARMS to the Guam Center for Biodiversity Research at the University of Guam, where another team of scientists waits to take the devices apart and inspect every organism. They photograph each plate, move out the large creatures, and then scrape them so the crusts and blobs sticking to the plates can be genetically sequenced to determine their identities.

Among the marine organisms found on the ARMS is a new species of dottyback fish that looks like someone put googly eyes on a slice of persimmon; a new species of sea slug whose body is peppered with yellow polka dots and tree-shaped protrusions; and a potentially new species of goby whose skin is so transparent you can see each one of its bones.

There were some familiar faces, too.

“This is an interesting and unusual hermit crab,” says Daniel Eisenhauer, a research associate at the University of Guam, holding up a petri dish. “It carries a bivalve shell rather than a usual snail shell. We’re quite pleased with this.”

During their expedition, Rocha and his colleagues collected 2,000 organisms. At least 20, Rocha thinks, are new species.

“Once we get the DNA, that number will increase tenfold,” he predicts.

(These deep-sea animals are new to science—and already at risk)

For Robert Lasley, a curator of invertebrates at the Guam Center for Biodiversity Research, witnessing the dramatic biodiversity from the depths was hard to process. He and his colleagues survey Guam’s shallow reefs every week in search of interesting specimens. But what they found on the ARMS was unlike anything he had seen.

“I never really cared too much about learning how to do these deep dives, but after seeing the new records and even new species,” he says, “I really want to start training so I can get to those depths.”

Deep sea dreams

For those who want to explore the unknown, Rocha says, there is no better place than the mesophotic.

Bähr, the Cal Academy postdoc who questioned Rocha’s sanity for diving to such depths, is completing her own deep diving rebreather certification.

“We’re [both] crazy,” she says, “We’re just blinded by the work.”

Bähr’s research focuses on deep-dwelling crabs and corals. She dreams of studying them in their natural habitat: “I cannot imagine anything better.”

Scientists who similarly aspire to venture below without the help of a submersible or ROV are in short supply. It is one of the reasons most mesophotic reefs in the twilight zone remain unexplored and, as a result, unprotected.

(Anya Brown is investigating microbes’ critical role in coral reefs)

“People tend not to protect the deep reefs,” says Rocha. “They don’t know they exist or don’t know what’s [living] there.”

He says the best way to get people to protect these places is to bring the reefs to them. He does this by publishing scientific papers, doing underwater photography, and hosting community events where people can see his specimens. The Steinhart Aquarium at the California Academy of Sciences currently has several fish on exhibit that he and his team collected in the mesophotic zone and brought back alive.

After the last ARMS had been recovered and the specimens preserved, Rocha and his colleagues gathered in a classroom at the University of Guam to bring what they’d seen on the edge of the twilight zone to light.

Wide-eyed students marveled at photos of a see-through shrimp, a yellow crab whose legs dwarfed its body, and a sunset-colored sea slug whose front and rear were indistinguishable. Their colors boggled the minds of both the students and scientists. The deeper you go, the fewer colors are visible, and yet these reefs contain every color of the rainbow. “We're trying to find out why,” says Rocha.

The students passed around jars containing the colorful creatures, discussing their contents and snapping pictures with fervor. Just days prior, no one on Earth knew some of these animals existed.

“I think that these new species might help us protect the region,” Rocha says.

As the last student filed out, he reflected on the twilight zone expedition. He had braved the depths, uncovered its secrets, and lived to tell the tale. Or as he describes it, “just another day at the office.”