These animals are nature’s clingiest lovers

For Valentine’s Day, we celebrate animal pairs that literally stick together.

Once you find that special someone, it’s hard to let go. The same is true for animals that literally attach themselves to their mates—some just briefly, and some for hours, or even for life.

In the animal kingdom, these specialized “clingy” behaviors help to increase reproductive success. From romantic amphibian embraces to deep-ocean dwellers that aptly demonstrate the phrase “two become one,” here’s a breakdown of the animal kingdom’s most clingy lovers in honor of Valentine's Day.

Two become one

When you live in dark ocean depths up to a mile below the surface, finding a mate can be tricky. That’s why a male anglerfish has a somewhat unorthodox technique for keeping a lover: biting her and latching on.

Eventually the bodies of the two amorous anglerfish fuse together, even joining circulatory systems. According to a March 2018 National Geographic article, “the male loses his eyes, fins, teeth, and most internal organs, only serving as a sperm bank for when the female is ready to spawn.”

His reward? Future generations bear his genes, while his sweetheart supplements him with the minimum nutrition he needs to survive. In some anglerfish species, females may have several males attached to them at a time and can produce young with all of them. (See “Anglerfish, taking romantic attachment to a whole new level.”)

Smothering her with love

The female red-sided garter snake, a species native to Manitoba, Canada, has no shortage of potential lovers. According to Christopher Friesen at the University of Wollongong in Australia, anywhere from 10 to 30 attentive males may pursue her at once, literally enveloping her with their love.

It all starts when the males wake up from hibernation in the spring, ready to mate. Sex-crazed males eagerly await a slower-stirring female, even forgoing food in the process. After two to four weeks of waiting for her to emerge, these singly focused males wrap around her and form what is known as a “mating ball.”

The whole thing lasts about 15 minutes and ends with one lucky guy breeding and inserting a gelatinous mating plug to repel other males, says Friesen. Once the female snake has reproduced, she’ll slither her way out from her ball of suitors to forage in nearby marshlands.

Although these male garter snakes are intense in their pursuit, they know when it's time to move on. "Courtship intensity and the number of males decreases slightly throughout copulation, and males detect that the female has mated, but not with them, and these males recommence searching behavior," says Friesen.

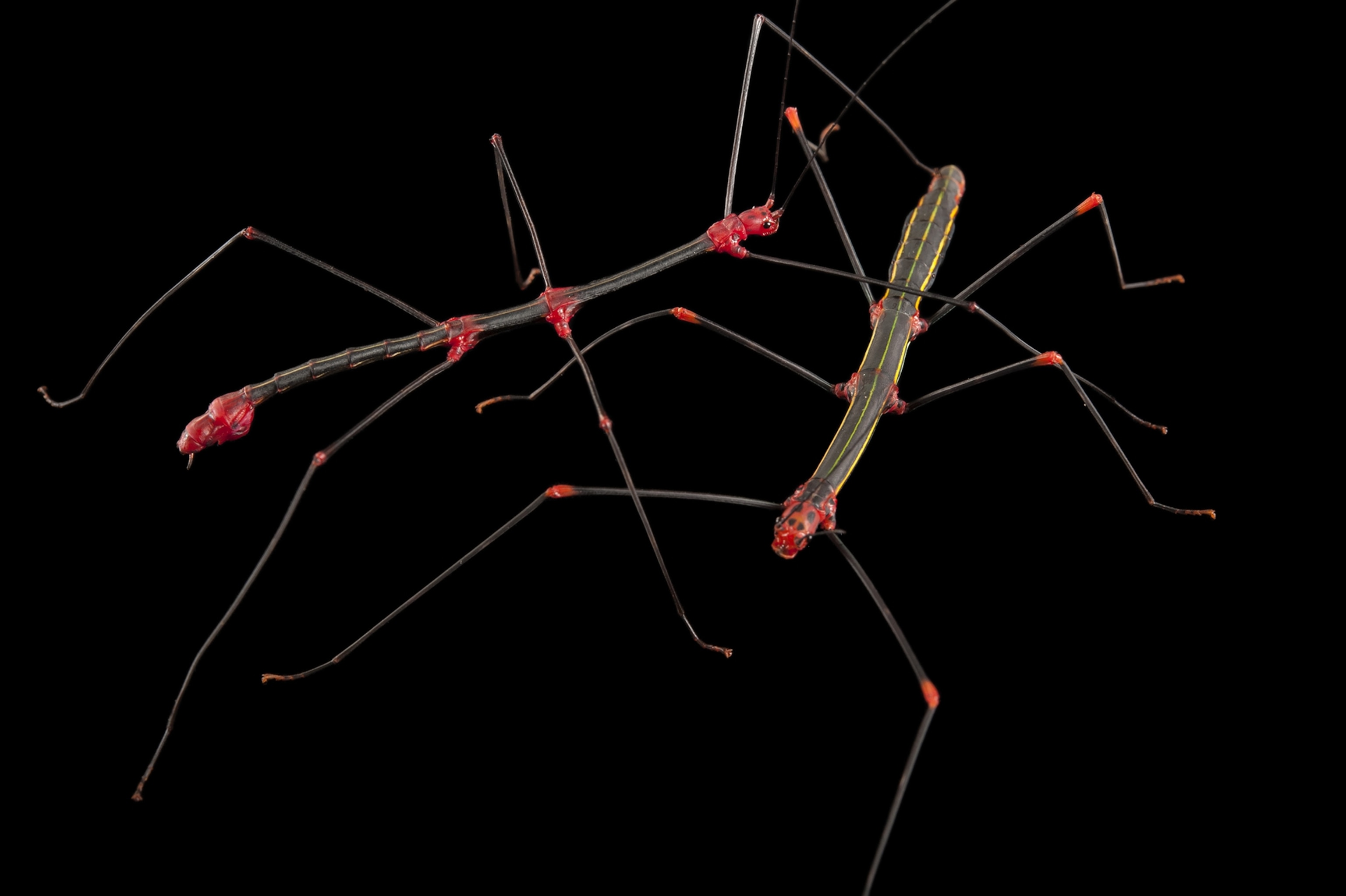

Sticking around awhile

Stick insects are known for the extreme duration of their mating—an Indian stick insect pair can remain coupled for a whopping 79 days, and mating itself can last days or weeks.

Scientists have observed other stick insect species love-locked for up to 136 hours, with as many as nine actual mating events during that time. Once a male Indian stick insect finds his target lady, he mounts and grips her using his feet. According to a 1978 study by entomologist John Sivinski, females rarely attempt to dislodge a suitor; when females did make the attempt to break free, they were never successful.

So why does the male “stick” around so long? He’s mostly guarding against rival suitors, or as Gwen Pearson, Purdue University’s Department of Entomology education and outreach coordinator, explains on her blog, the male probably hangs around in order to mate repeatedly, but also to “drive off other males that want to get lucky.”

Romantic embraces

Except for a few species, frogs have a special way of pairing up. A male fertilizes the female’s eggs on the outside of her body, doing the job as soon as the eggs emerge.

To assist in his efforts, the male engages in the ultimate romantic gesture—a long hug known as amplexus (Latin for “embrace”). To position himself, he’ll place his hands on the female’s waist and won’t let go for hours or even days—duration varies by species. One pair of Andean toads was observed embracing for four months, according to the American Museum of Natural History.

These amphibians also think outside of the box when it comes to amplexus. Frogs display seven known sex positions, which vary by species. (See “New mating position adds to ‘frog kama sutra.'")

It’s not always the male who leads the embrace. According to a 1986 paper in the journal Herpetologica, with her mate mounted atop her back, the female coquí frog uses a “reverse hind leg clasp” during amplexus. The coquí, native to Puerto Rico, is one of the few frog species that fertilizes eggs internally, and the female’s acrobatic leg clasp is believed to aid in sperm transfer. Amplexus is not unique to frogs and toads—newts and horseshoe crabs also use this coupling technique.

Babies that can’t let go

It’s not always lovers who are clingy; sometimes babies stick to copulating couples. Bonobo societies are known for substituting lovemaking for aggression (unlike their close relatives, common chimpanzees). That’s probably why researchers often observe baby bonobos clinging to mom during sex.

While it’s not uncommon for primate babies to hang on to mother when they’re young, bonobos have “much more non-conceptive sex” than other species of great apes, according to Vanessa Woods, research scientist in the Evolutionary Anthropology Department at Duke University, meaning that sometimes they do it for reasons other than to procreate, including to relieve tension or bond.

Bonobo babies stay with their mothers until about age five, says Woods, and cling less as they mature. (See “Bonobo males get sex with help from their mums.”)

Whether waiting patiently for a mate and enveloping her, or engaging in long, romantic embraces, all these clingy lovers have one end goal: to pass along their genes. Their mating techniques, while sometimes extreme, are merely special adaptations that help their species survive.

Tina Deines is a freelance journalist based in Albuquerque, New Mexico.