The first photographs to capture wildlife at night

When George Shiras published his wildlife photographs in National Geographic it transformed the medium with his novel use of flash and the first camera traps—and changed Nat Geo forever.

Looking back to that period, many years ago, when the finger eagerly pulled the trigger and the eye anxiously sought to pierce the momentary veil of smoke between the gun and its intended victim, and then to that later period, when the simple pressing of a button captured, for all time, the graceful image of the hunted quarry, one becomes conscious of a peculiar mental evolution. Success in the hunting field should properly be dominated by a keen sense of pleasure which, if absent or but a minor incident in the chase, indicates a misdirected effort.

We all know, today, that the average successful and contented sportsman will admit that the mere taking of animal life is regarded as an apparently unavoidable incident in the gratification of desires existing wholly apart from the shedding of blood. One purpose of this article is to show that the time has come when it is not necessary to convert the wilderness into an untenanted and silent waste in order to enjoy the sport of successfully hunting wild birds and animals. So many advocates of hunting with the camera have been heard of late, that my voice need no longer be raised in behalf of this sensible and attractive pastime, were it not that the majority of such writers, coming from the ranks of the naturalist and the amateur photographer, almost invariably decry the sportsmen as a set of ruthless butchers, blind alike to the beauty of wildlife and to the ethics of ordinary decency.

No greater error could exist or its effects be more unfortunate. Sportsmen, the world over, constitute a high order of citizenship; generous, self-reliant, and faithful, they have done much in keeping up the virility of the race, and in leavening those debasing influences of over-civilization. The all-inspiring motive of every true sportsman is fair play and a fair chance to the animal or bird whose life may pay the forfeit in the contest.

The salmon must be lured from the foam-crested pool with a fragile, artificial fly and landed with a rod so light that perhaps an hour may pass before the hand-net is used; the grouse must be plucked from mid-air by a tiny gun, and the mountain sheep shot at 500 yards with a bullet smaller than a pencil tip. Within the ranks of civilized man, where do such rules prevail? In business competition, in the race for social and public honors, in all those contests wherein Mammon or Ambition holds the tiller and guides man on to victory or defeat, how often is the “square deal” the guiding light?

Would any one suppose if President Roosevelt, after his graduation from aesthetic Harvard, had spent his life within the narrow sphere of his birth that his career would have been the same? Or that if he had merely lived within a Dakota ranch, with his hand on the branding iron and his mind upon the cash value of each season's round-up, that his nature would have been the same? Self-reliance, quickness of purpose and of action, and a broad view of man as Nature's noblest creation seldom come to one who forms but an insignificant atom in a conventional assembly of mankind. While, therefore, it becomes my part to point out an additional and perhaps wholly superior method of enjoyment for the wilderness hunter, I can but protest against any crusade which by maligning the sportsman may prejudice him against the camera, or, what is even worse, lead him to give up his yearly visits to Nature's realms, wherein lies the inspiration for a better and stronger life within the city's walls.

Many years had elapsed before the advent of the hand camera made game photography at all practicable, but within two seasons, after my experiments with it, the full possibilities began to be most apparent. It may, therefore, be of interest in this connection to reprint a few extracts from the first article ever published [Forest and stream, 1892] advocating the use of the camera in the field of sportsmanship:

“A sportsman's life consists largely of three elements—anticipation, realization, and reminiscence. We look forward to the trip by rail, by canoe, and then perhaps a tramp on foot into the heart of the wilderness. Then come the camp and its pleasant environments, and that lucky, radiant day when the early morning sun casts a glint upon the branching antlers of a mighty moose, as, half concealed in the thicket, he furtively and slowly browses his way along, the breathless wait until the neck or shoulder become exposed, the shot, and then—success—that is, sudden death; or perhaps success delightfully intensified by a hasty scramble after the mortally wounded beast on a blood-stained trail, at the end of which we triumphantly find our victim dead or dying.

“Would that we could realize that what is game to the rifle is game to the camera! Every true sportsman will admit that the instant his noble quarry lies prone upon the earth, with the glaze of death upon the once lustrous eye, the graceful limbs stiff and rigid, and the tiny hole emitting the crimson thread of life, there comes the half-defined feeling of repentance and sorrow. The great desideratum, after all, consists of neither meat, nor horns, nor hide, for the very next day we may be at it again, if able to do so without too severe a tax on our conscience. Therefore we reach the conclusion that much of our large game, when skillfully hunted and dispatched by the modern sportsman of decent instincts, owes its extinction to an abnormal, if not fictitious, reason.

“Surely we do not travel a thousand miles, indifferent to time, labor, and expense, to get a few hundred pounds of wild meat, probably not half so toothsome as the domestic cuts in the market stalls of our own town or village, and costing frequently more than their weight in precious metal. Neither can hide nor antlers compensate us, except as visible evidence of our skill, for the taxidermist is ever ready to supply specimens of more surpassing beauty at half the cost. Some time we will come to recognize the fact that the real enjoyment of the outing in the woods or upon the water arises mainly in the freedom from business cares and the artificiality of city life, with the opportunity of indulging in some health giving, exhilarating recreation, whatever name it goes under. This is especially true of the non-professional hunter of large game.

“We contentedly cast a fly all day into a swirling pool and may hardly get a bite, when a stick of dynamite would have covered the surface with a crate of trout or bass. We hopefully sit for hours shivering on the limb of a mountain oak and may contentedly return empty-handed, when the steel trap, staked pit, or set gun would have done the work equally well. The killing of large game becomes improvident, wasteful, and cruel whenever the amount shot exceeds the reasonable use for food.

“Many would exclaim that such a rule would put an end to every sportsman's camp; that perhaps the very first day luck would bless the greenhorn of the party with a fortuitous shot, and then the ten days' vacation would slowly elapse, while the rifles rested in the rack and the veterans sorrowfully gorged themselves on musty buck until the time arrived to pull up stakes, pack the duffle, and depart for civilization. This may be true, so far as it relates to the cylinder of steel. Just substitute the camera gun, with its accurate tube of brass, and you are again equipped for sport. The game bag is never full, one's pleasures never satiated.

“Every camera hunter must admit that more immediate and lasting pleasure is afforded in raking a running deer from stem to stern, at twenty yards, with his 5 x 7 bore camera than driving an ounce ball through its heart at 100 yards. Then think of the unlimited freedom of this noiseless weapon. No closed season, no restriction in numbers or methods of transportation, no posted land, no professional etiquette in the manner of taking your game, but you can pull on a swimming deer or an elk floundering in the snow, take a crack at a spotted fawn, bag the bird on its nest, or string your cameras out like traps with a thread across the runway and gather in the exposed game-laden plates at nightfall with out any scruples about being called a pot hunter or a game hog.

“While it is true that whatever is game to the gun is game to the camera, it must be particularly noted that the latter's field is much enlarged by the immense variety of birds, animals, and reptiles which are never considered fair prey for the huntsman. Game in the early days was declared to be only such as was edible, and this standard exists at the present time, though certain predatory animals and those possessing handsome pelts have at times been pursued by sportsmen in the vain effort to broaden the ever-narrowing sphere of their activity. Non-game birds and animals outnumber the edible class a thousand times, and it is this great advantage which makes and will continue to make camera hunting the more attractive and permanent of the two methods of pursuing wild life, and at the same time largely counterbalance the greater difficulty of photographing birds or animals when compared with the ease of shooting the same under similar circumstances; for the difference between stalking within rifle range of a moose, a deer, or a bear and getting within a few yards is of the same, in broad daylight, with the camera, need not be pointed out.

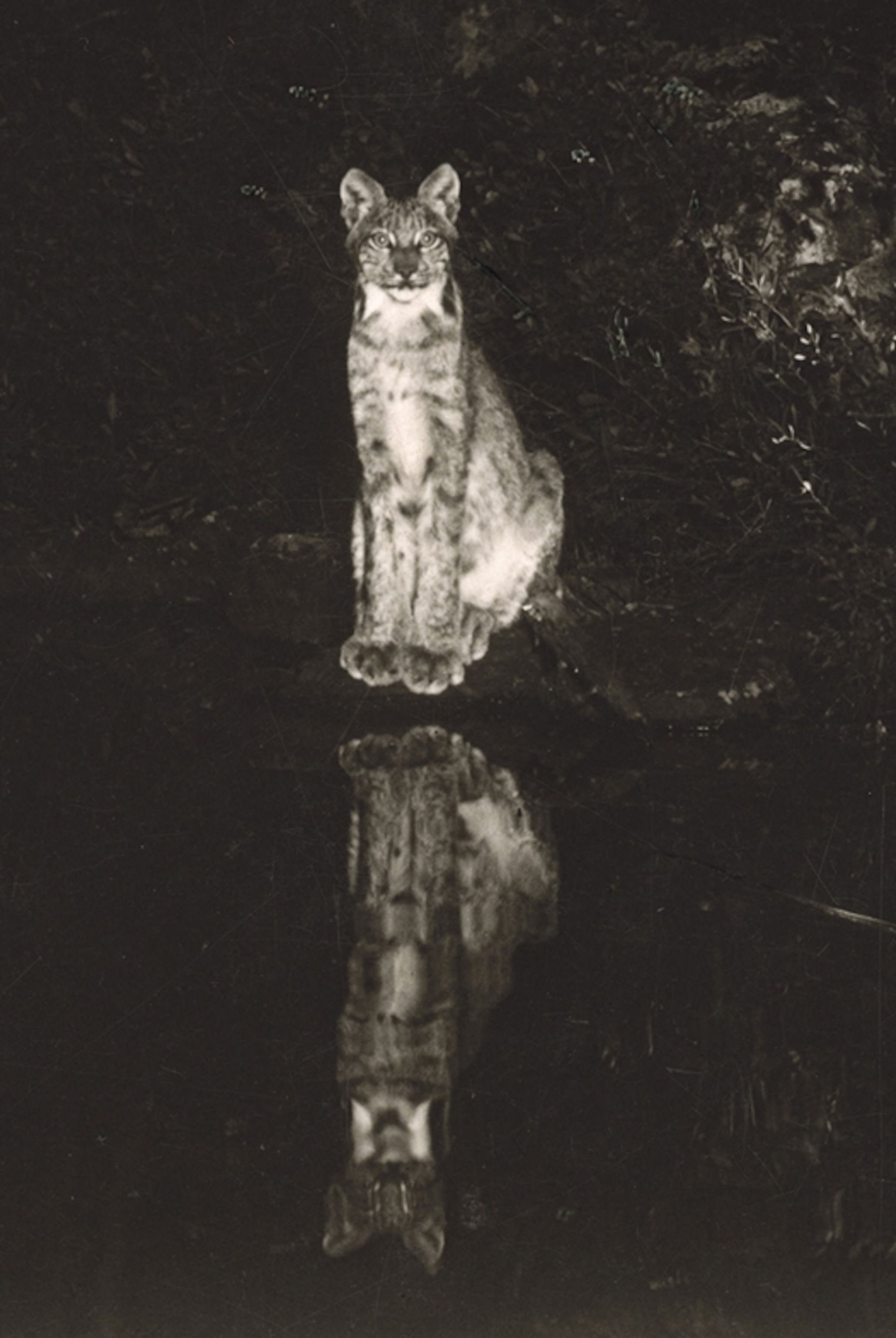

“The restrictions upon the gun which prevent the sports man hunting the golden eagle, the snowy owl, the graceful flamingo, the gulls, herons, hawks, and those hundreds upon hundreds of birds, varying from the tiny hummingbird to the mighty condor, do not apply to the man with the camera or prevent him from picturing the myriads of animal life, wherein the porcupine, the wild cat, the coon, the wolf, the alligator, or the sea-lion may be considered the fairest and most attractive kind of game, because requiring the same skill and the same patience which leads the sportsman to pursue to the death those varieties of animals which a fictitious reason allows them to kill for sport, under the assumption that their edible qualities is a justification.

“It is only within the last few years that compact photographic appliances, quick shutters, rapid dry plates and films have made possible successful work on large game, or otherwise some of us might have reformed before. The longer we have hunted and the greater our success, the less able are we in after years to recall many of such scenes with satisfactory distinctness. We have taken too many mental photographs, so that our gray film fails to be clearly and permanently impressed with the thousand scenes of slaughter the eye has successfully focused. Not so with the camera hunter. Each year adds value to his successful shots, and when he departs for the happy hunting grounds his works live on forever.

“Generally speaking, it is a patent fact that in the more remote portions of our country the largest of the great game fall singly and in bands without any pretense that the meat itself can be possibly used, and this is especially true of the moose, elk, caribou, and formerly of the buffalo. In many instances the horns and hide become a handsome trophy, but at a cost far exceeding their commercial value. Wherefore this anomalous state of affairs?

“If the incentive pulling the trigger is the flesh pot or the purse, the case is incurable. To the professional hunter the camera would be a hollow mockery, and a plate containing the image of a deer instead of a solid chunk of venison a Barmecidal feast. Killing game by the professional is purely a matter of business, like cutting cordwood, and therefore gauged upon a different, but nevertheless much more rational, principle than the one which governs most of us in hunting.”

The above plea for the camera in hunting has since been supplemented by many other sportsmen and naturalists, until, at the present time, hardly a month goes by that some new and forcible reason is not given for the substitution of the camera for the gun.

While a number of the present illustrations were taken in the daytime, this method of photography is now so well known that I will not attempt to describe such pictures in detail; but in view of the fact that I was the first to attempt flashlight pictures of wild game, and for the first fifteen years was the sole occupant of this attractive field of photography, it may be of interest to the readers of this article to learn something about this rather odd way of picturing wild animals, at a time when the hunter ordinarily is sound asleep.

When going out for the first time in the dead of night, in the silent, trackless forest, or upon the placid bosom of some little lake, searching for game photographs, with the way feebly lighted by a bull's-eye lantern on one's head, or the lamp fastened to a stick in the bow of a frail canoe, one is apt to think it is a venture unlikely to meet with much success, however great the novelty of such an expedition.

However, the pictures herein produced are but a few of the many obtained in the past, and indicate that night hunting with the camera, while of course difficult, is still not barren of results.

Like all pastimes worthy of permanent existence, considerable skill and patience is required, doubly rewarded, first by the fascination of life amid Nature's secret haunts, and secondly in the beautiful and permanent game pictures which the camera hunter obtains when his efforts are properly directed.

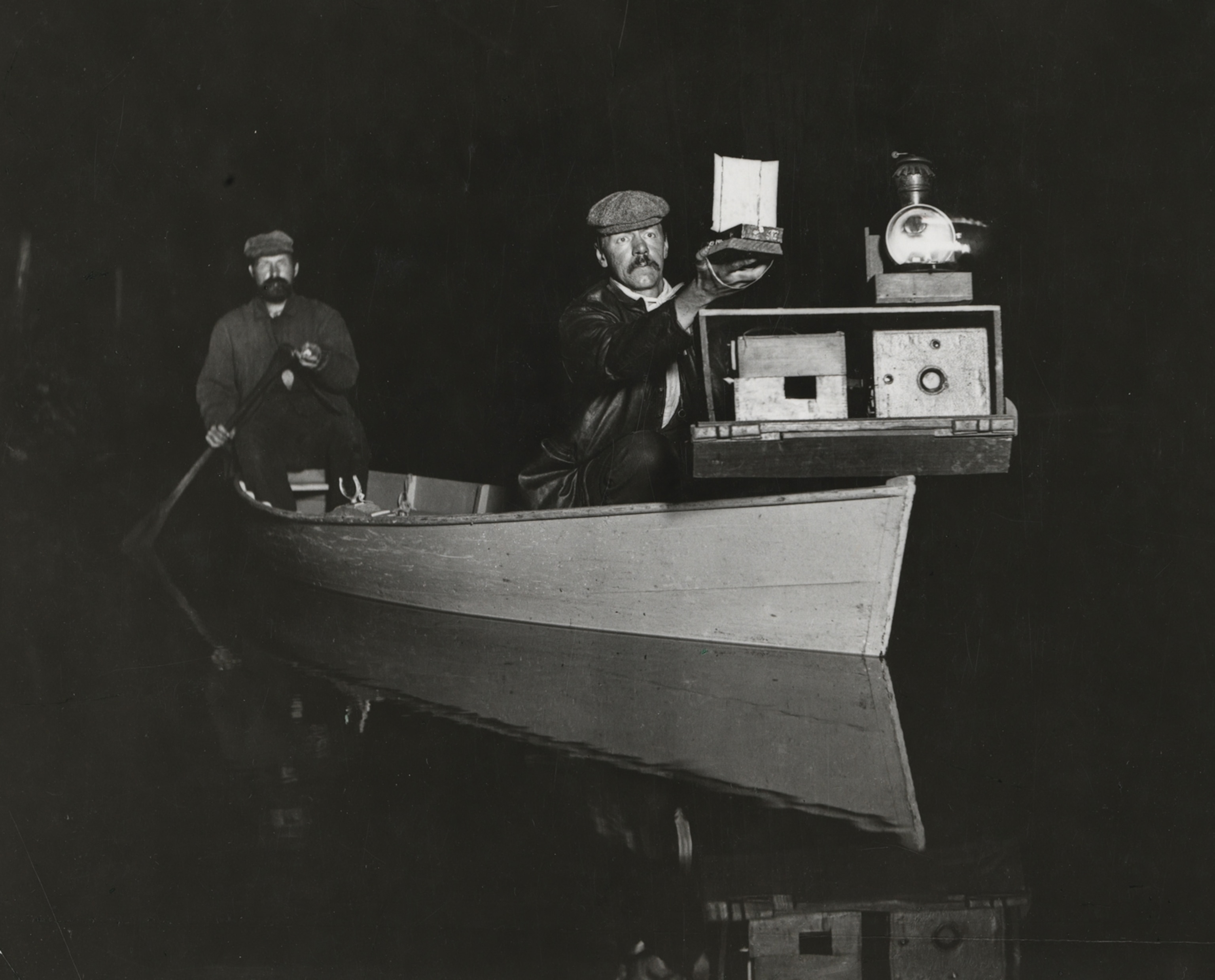

A brief description of how these night pictures were taken may not be out of place. Ordinarily it is preferable to seek the game along the water-courses, and, as most wild game are largely nocturnal in their habits, the writer has usually sought his game in a boat rigged especially for such purpose.

In the bow of a light fourteen-foot boat is set a frame upon which two cameras are placed, focused at from thirty to forty feet; above this is placed a lamp with a strong reflector, which throws the rays directly in front of the boat.

The deer and the moose feed among the lily pads and grasses along the edge of the stream or lake. They are not ordinarily frightened by the approach of a light, their curiosity being very strong and the bright rays of the lamp blinding them, so that they cannot see the boat or its occupants. This method of approaching game is well known to hunters, and is called “hunting with a jack-light.” It has been the subject of some discussion among the sportsmen as to whether this method is legitimate, nearly all contending that it does not give the deer a chance for his life, which true sport demands.

That, however, is a question which does not concern us at present, as our hunting is not destructive.

Having selected a dark, warm night, a flash-light hunter prepares his cameras, lights the jack-lamp, loads his flash-light apparatus with magnesium powder, and in his canoe pushes out into the silent waters of the lake or river. The paddle sends the slight boat ahead so easily that no sound is heard except a gentle ripple, unnoticeable a boat's length away. The wooded banks are wrapped in deepest shadow, only the sky-line along the crest showing their course.

At the bow of the boat the bright eye of the jack-light is turning from side to side, cutting a channel of light through the waves of darkness, showing, as it sweeps the banks, the trunks of trees and tracery of foliage with wonderful distinctness.

Soon the quick ears of the men in the boat detect the sound of a deer feeding among the lily beds that fringe the shore.

Knee-deep in the water, he is moving contentedly about, munching his supper of thick green leaves. The lantern turns about on its pivot and the powerful rays of light sweep along the bank whence the noise came. A moment more and two bright balls shine back from under the fringe of trees; a hundred yards away the deer has raised his head and is wondering what strange, luminous thing is lying out on the surface of the water. Straight toward the mark of the shining eyes the canoe is sent with firm, silent strokes. The distance is only seventy-five yards, now it is only fifty, and the motion of the canoe is checked till it is gliding forward almost imperceptibly.

At this point, if the hunting were with the firearm, more largely employed, there would be a red spurt of fire from under the jack-light, and the deer would be struggling and plunging toward the brush; but there is no sound or sign of life, only the slowly gaining light.

Twenty-five yards now, and the question is, Will he stand a moment longer? The flash-light apparatus has been raised well above any obstructions in the front of the boat, the powder lies in the pan ready to ignite at the pull of a trigger; everything is in readiness for immediate action.

Closer comes the boat, and still the blue, translucent eyeballs watch it. What a strange phenomenon this pretty light is!

Nothing like it has ever been seen on the lake during the days of his deerhood.

Fifteen yards now, and the tension is becoming great. Suddenly there is a click, and a white wave of light breaks out from the bow of the boat-deer, hills, trees, everything stands out for a moment in the white glare of noonday. A dull report, and then a veil of inky darkness descends. Just a twenty-fifth of a second has elapsed, but it has been long enough to trace the picture of the deer on the plates of the cameras, and long enough to blind for the moment the eyes of both deer and men. Some place out in the darkness the deer makes a mighty leap; he has sprung toward the boat and a wave of water splashes over its occupants; again he springs, this time toward the bank; he is beginning to see a little now, and soon he is heard running, as only a frightened deer can, away from the light that looked so beautiful, but was in fact so terrifying. What an account he will have for his brothers and sisters of the forest of a thing which he himself would not have believed if he had not seen it with his own eyes. In the boat, as it slips away from the bank, plates are being changed and the cameras prepared again for another mimic battle.

Sometimes the pursuit is varied by letting the deer take its own picture.

A string is passed across a runway, or other point where the deer are likely to pass, which, when touched, sets off the trigger and ignites the magnesium powder. The same method can be used for daylight pictures, except that here a slender black thread is laid across the path, one end of which is attached to the shutter of the camera. The shutter revolves as soon as there is any pressure upon the thread, and a picture of any passing object is taken instantaneously. Not the least interesting part of this species of photography is that the operator does not know until he develops his plates what manner of beast, bird, or reptile has caused the shutter to open.

So the days pass on and the nights, with all the scents of the woods and the thousand charms of nature and of wildlife; all the zest of pursuit, all the setting of the wit of man against the wit of wild beast, all the preparation for the chase, and all the cunning of pursuit, to be rewarded with tangible evidences of human skill and patience which will long outlast the details of the scene as caught by the most powerful memory.