Python Moms Care for Their Young, Surprising Experts

A new study from South Africa observed wild snake mothers protecting and warming their young for weeks after they emerged from eggs.

At lengths reaching up to 16 feet, cold-blooded southern African pythons are not the type of mothers you want to mess with.

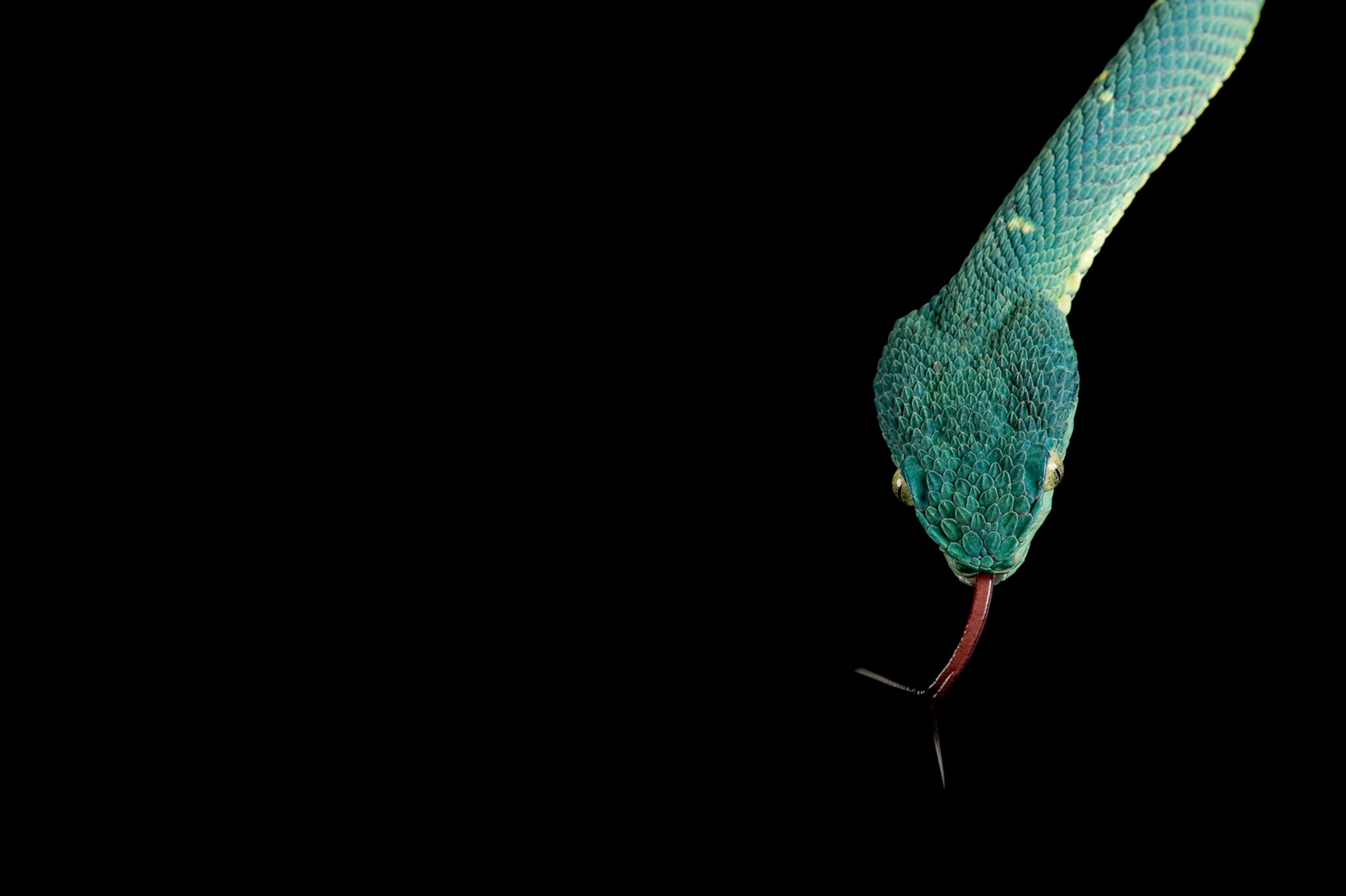

Heat-sensing lip scales that can detect warm blood to snack on may not scream maternal instinct, but a new study has revealed the species lays eggs and keeps care of massive, writhing balls of python babies for about two weeks before cutting them loose to the harsh outside world.

"Our pythons are staying with the eggs. The eggs hatch, then the mother and the babies have this interaction for the first two weeks after they hatch," says Graham Alexander, a reptile professor at Wits University in South Africa and the author of a study recently published in the Journal of Zoology.

Alexander studied the snakes using radio transmitters and by installing cameras into their egg-laying burrows underground for seven years in the Dinokeng Game Reserve north of Pretoria. While live-birth giving vipers have been observed showing maternal behavior, his discovery is the first example of egg-laying snakes caring for their young after hatching.

Southern African pythons are one half of the species that used to be called African rock pythons before that was split into northern and southern varieties in 1999, Alexander says. The southern variety is a little smaller than the northern variety, growing to an observed length of 16 feet and weighing up to 130 pounds. Adults can possibly live up to 30 years, and they can regularly take down antelope like grey duikers or impala.

Cold-blooded Daycare

The southern variety lays clutches of eggs that hatch into around 40 to 50 needy babies, often in underground aardvark burrows. After hatching, babies are often timid, poking their heads out but remaining in their eggs for up to two days, while the mother continues to coil around them.

Alexander believes they do this to protect the young. When he approaches mothers in the wild they are often a lot more timid than you might expect for such a large predator.

"She just bolts for the hole," he says, adding that mothers will occasionally show aggressive behavior once inside.

It could also have to do with the development of their young. The newly hatched babies are awkwardly plump due to leftover undigested egg yolk. Alexander believes this is one of the reasons why the mothers hang around—the babies are less mobile, and hence more vulnerable at this stage of their life to predators. The mothers provide protection for the babies, and also the warmth to help them digest the egg yolk until they are mobile enough to find their own food, which usually consists of mice, rats, and small birds.

Back in Black

Alexander says he also observed another first for the species. Breeding females change color from their normal blotched olive, yellow, and brown camouflage patterns to a straight black. That change makes them appear like a "big black gum tree log laying in the wild."

He believes the black helps the cold-blooded mothers absorb more sunlight when they bask in the sun, which they can subsequently transfer to their eggs or newly hatched snakelings back inside the burrow.

"I've even had them reach temperatures of [104 degrees Fahrenheit], so warmer than a mammal," he says.

Rearing 40 to 50 baby pythons is not an easy job for mothers, which only breed about once every three years. "They take a long time to recover after a breeding event," Alexander says.

Rockwell Parker, an assistant professor of biology at James Madison University in Virginia, calls the study fascinating.

"It makes snakes so much more interesting than people give them credit for," he says.

Reptile breeders have noticed before that python mothers coddle their young in captivity, but Parker says this study is part of an "awakening" on the part of biologists.

The Climate Factor

Another factor could come into play regarding the pythons' motherly behavior. The site Alexander studied is at the edge of the range of the pythons, due to a colder climate a little farther south. While adult snakes can tolerate colder temperatures, Alexander says the limiting factor is mothers. Below 82 degrees Fahrenheit, python eggs either don't hatch, or often hatch deformed.

Alexander is also researching how climate change will affect this population range in the future, and he isn't sure whether the maternal behavior represents an adaptation by southern African pythons to cope with cold temperatures at the extreme edge of their range, or whether the whole species (and possibly their northern cousins) carry this motherly instinct.

He says this discovery could help scientists better understand the evolutionary path that led to maternal care in various animals.

"Even if you go back 20 years, when people suggested that snakes had any type of parental care, people scoffed at you," he says.

A mother python's tolerance for her children doesn't last long, though. After about two weeks, they will often ditch the kids permanently and set out, presumably to find something to kill.