Scientists put sharks in a tank full of toys. What they saw surprised them.

New video shows sharks swimming through hoops, and picking them up with their noses. It sure looks like they are having fun. But researchers are divided.

Scientists have no problem using the word “play” to describe dogs who fetch sticks or cats batting around yarn. But with sharks, it’s a whole other ballgame.

A new study in the journal Applied Animal Behavioral Science describes sharks interacting with human toys in a way that resembles play, though the word “play” does not appear in the paper.

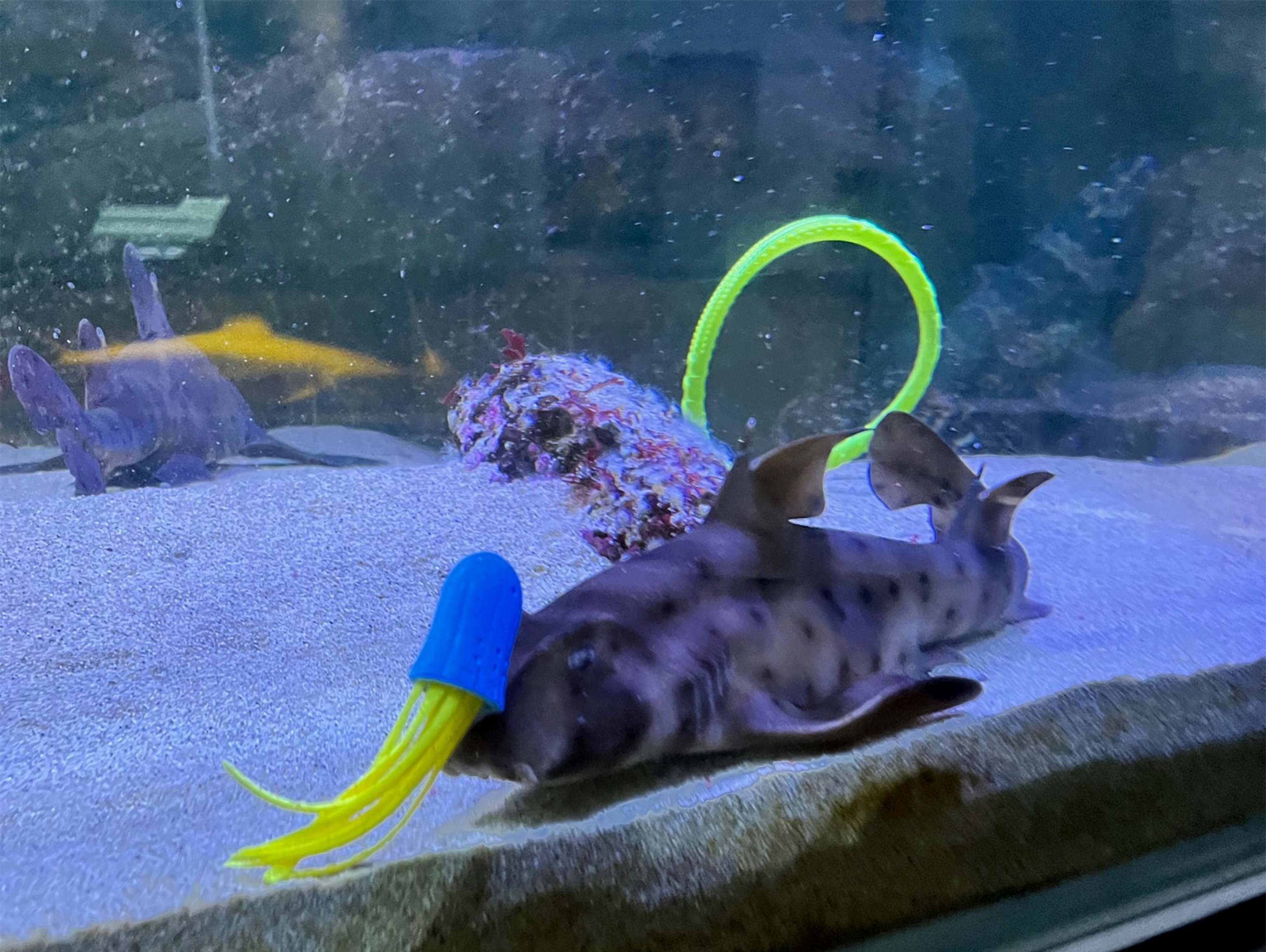

Video footage from the study shows sharks swimming through hoops, picking them up with their nose, and flicking the toys with their tails, and bumping or biting them. Like they do in the wild, they would also rush towards one toy and then abruptly change direction last second.

But does this amount to sharks playing?

Study authors say that to claim that an interaction is “play,” the behavior needs to be contrasted with “normal” behavior, trigger a sense of reward in the brain of the animal, and happen when the animal is in a relaxed, unstressed context. Since the study didn’t rigorously address those points, they understood why, according to them, journal reviewers told them to remove the word from their paper.

Still, that doesn’t mean sharks can’t play.

“If you ask me casually, that's what we thought they were doing,” says Patrick Sun, professor of ecology at Biola University and co-author of the study. “We thought they were playing, and I think if we designed a more rigorous study we would prove that they're playing.”

(First-of-its-kind footage reveals 3 endangered sharks mating—all at the same time)

A tank full of toys

Virtually nothing is known about play behavior in sharks. In general, on a behavioral level, “most research still centers on predation, and only recently have we begun to learn more about mating. But we still know very little about sharks’ social behavior, communication, cognition, navigation, daily routines, and, of course, play,” says Autumn Smith, a shark ecologist at Biola University in California, and lead author of the study.

To test the waters of potential shark play, Smith and her team conducted experiments at the Cabrillo Marine Aquarium in San Pedro, California. There, the team worked on a tank where 13 individuals from four different species co-exist: horn sharks (Heterodontus francisci), swell sharks (Cephaloscyllium ventriosum), leopard sharks (Triakis semifasciata) and a California skate (Caliraja inornata).

Once a week, when the sharks and the skate got feed, the researchers would go to the aquarium and fill the tank with toys such as plastic squids, plastic rings and thin, heavy tubes that sink to the bottom of the tank. They would do that one hour before the staff started feeding the fish. Then, when it was feeding time, they removed all the toys from the tank. 30 minutes after the sharks and the skate finished eating, they would put the toys back in.

During both sessions, the team recorded the animals in the tank interacting with the toys. They kept doing this procedure once a week for 12 weeks during 2022.

The observations revealed an unseen side of sharks. “I was genuinely surprised how much interactions there were,” says Smith.

During the first sessions, the sharks and the skate didn’t interact much with toys, but as time went by, they became more and more interested.

“Even within the species, there were personalities that started to develop,” says Smith. Some individuals were more motivated to interact with the toys while others showed less interest.

Some even seemed to be possessive with a specific toy and hang on top or under it. Among all species, leopard sharks were the ones that interacted more with the toys.

The sharks and the skate also interacted with toys more after feeding. This hints towards the idea that “there is other motivations within them, a different cognitive basis that aren't hunger,” says Smith. “That's something that we're trying to figure out more about.”

(Watch orcas team up to hunt great white sharks in rare video)

Play or not play? That is the question

But are these sharks playing?

Elisabetta Palagi, a comparative ethologist at the University of Pisa who wasn’t involved in the research, thinks it's hard to say whether what the sharks were doing can be defined as “play or if it's an exploratory behavior.”

Palagi also points out that, after some time, the shark motivation toward the toys seems to decrease. She thinks this points more toward an exploratory behavior where the sharks, after exploring the objects for some time and realizing they don’t provide food or anything else, lose interest in them.

(Rare image of great white shark captured off the coast of Maine)

When you are dealing with species so different from us, whose behavior is often difficult to understand and is understudied, it is better to maintain "a more cautious approach," says Palagi, adding that a longer observation might have revealed something more about the behavior.

“I wouldn't say necessarily that they have shown this is playing but I do think it raises some interesting questions about, potentially, is that what's going on?” says Yannis Papastamatiou, a predator ecologist at Florida International University who wasn’t involved in the study. “I would say cautiously that there's a lot we don't understand about these animals,” adds Papastamatiou.