Sharks are thriving in some marine parks—but not others. Why?

A study of marine parks spanning Mexico to Ecuador found key differences that allow ecosystems to flourish.

As Simon McKinley dropped down in the water, everything went dark. He’d seen sharks from the surface but now—gradually descending on his scuba dive—so many scalloped hammerheads were schooling together that they were blocking the sunlight. “You couldn't turn anywhere without seeing a shark,” he says.

McKinley, a spatial ecologist at the Charles Darwin Foundation, was surveying shark populations at the remote Darwin and Wolf Islands in the Galápagos. It’s “one of the sharkiest places in the world,” he says. That also makes it a notably healthy ecosystem in which marine life can thrive.

It’s one of seven marine protected areas (MPAs) across the eastern tropical Pacific from Mexico to Ecuador that McKinley studied for his new paper on shark abundance published today in the journal PLOS One. The study received funding from National Geographic Pristine Seas.

The findings reveal a stark contrast. In remote, highly protected areas with strong enforcement against fishing, sharks are thriving—but protected areas closer to the coast where more fishing occurs had a concerning lack of predators. The difference in sharks counted shows that not all parks are created equally even if they seem that way on paper.

As countries around the world work toward the United Nations’ global goal of protecting 30 percent of the ocean by 2030, the study authors say conservation leaders need to keep this difference in mind if they want to implement protections that have tangible benefits for the ocean.

What sharks can tell us about an ecosystem

As “managers of the reef,” sharks keep habitats healthy by eating sick fish or excessive populations, preventing any one species from overrunning the ecosystem, says McKinley.

MPAs are like national parks and have varying rules about how much human activity is allowed. In fully protected zones like Malpelo Fauna and Flora Sanctuary in Colombia, all human activity is forbidden, while some protected areas allow fishing, such as Galera-San Francisco Marine Reserve in Ecuador.

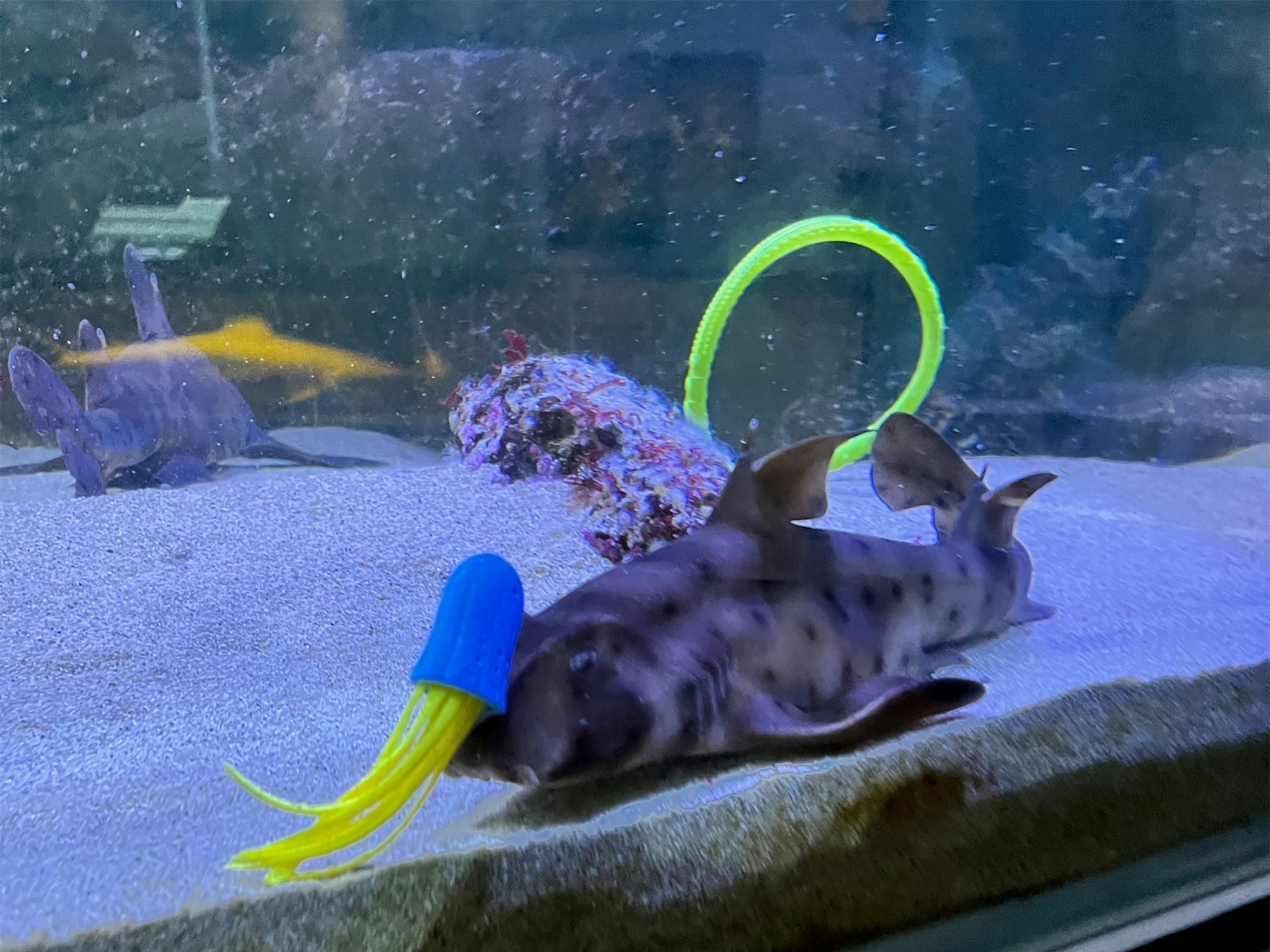

To determine whether these varying rules affected sharks, scientists spied on them using non-intrusive video devices deployed at around 65 to 80 feet deep for at least 100 minutes.

The scientists—including researchers from Galápagos National Park Directorate, National Geographic’s Pristine Seas initiative, and several regional institutions—used underwater cameras called baited remote underwater video systems (BRUVs) to observe sharks in seven marine parks found throughout Ecuador, Costa Rica, Colombia, and Mexico. These devices used oily fish to attract predators, and researchers then counted how many animals arrived to check out the scrumptious snack.

In hard-to-reach MPAs, which ban or strictly police fishing—the Galápagos, Malpelo, Clipperton, and Revillagigedo islands—the study authors consistently saw a large number of sharks, says McKinley. But coastal areas near human activity—Machalilla, Galera-San Francisco, and Caño Island—told a different story. “We only saw four individuals across over 30 deployments on the coastline,” he says of their survey of all three areas.

Although Caño in Costa Rica is technically off limits to fishing, illegal fishing has been recorded inside its boundaries.

Close to the coast, sharks are at higher risk of a number of human activities, such as habitat destruction, pollution, and nearshore fisheries. “It’s easier [and] cheaper for them to fish close to the coast than it would be to fish way offshore,” which can be very dangerous, says Samantha Andrzejaczek, a research scientist at the Hopkins Marine Station of Stanford, also not involved in the study.

The study showed that properly enforced no-take areas farther from shore resulted in more shark and fish populations visible on camera.

“These highly protected MPAs are absolutely effective in restoring these large fish that we've been so efficient in eliminating for the last 50 years—or longer—100,” says Rory Moore, head of conservation at Blue Marine Foundation, who was not involved in the study.

The key difference that influenced how healthy these ecosystems were was clear: fishing.

“Marine protected areas that allow fishing do not work,” says Enric Sala, a study co-author and founder of National Geographic Pristine Seas. Sala, also a National Geographic Explorer-in-Residence, adds that just three percent of the global ocean is protected from it."

Why effective marine parks matter

One third of sharks, rays, and chimaeras are threatened with extinction.

To protect them, the researchers want to see more MPAs with stricter regulations. “It needs to be properly enforced,” says Andrzejaczek. “Otherwise, it's not doing its job.”

Many shark species migrate long distances, which is why Sala says setting up protected areas in the ungoverned High Seas is also important.

In addition to what some scientists see as a moral imperative to protect marine species from disappearing, studies also suggest there are economic benefits to more strictly protected marine reserves.

Mirroring the decline of sharks and rays, more than one third of fish species are overfished, meaning they can’t reproduce fast enough to replace what’s removed. “It's like having a checking account where everybody withdraws and nobody makes a deposit,” says Sala. A protected area acts like an investment account that provides “compound interest and produces returns that we can all enjoy,” he says.

Fishers can reap the benefits of protections when they “fish just outside the marine protected area, where we have what's called a spillover effect,” and fish populations are thriving, says Andrzejaczek.

These benefits are already being seen in countries at the forefront of ocean protection, such as Palau, Niue, Seychelles, Costa Rica, Colombia, Chile, and Gabon, which already have effective protections for 30 percent of their waters.

“These leaders understood that they need highly protected areas if they want their fishing and coastal economies to have a future,” Sala says. “You don't need to be rich to protect the ocean. You just have to be smart.”