These 5 New Snake Species Suck Snails Out of Their Shells

The names of the snakes were auctioned off, and funds from the event will go toward preserving some of the species.

After a long night of searching for snakes in Ecuador, Alejandro Arteaga and his team of researchers got ready to retire. The evening’s excursion, in a swampy region of rain forest, hadn’t yielded any snakes from a species they were seeking.

But as rain poured down on the drive back to camp, Arteaga, a Ph.D. student at New York City’s American Museum of Natural History, decided to make one last stop.

“The road was so densely covered with vegetation that you could stretch your hand out of the car and grab the leaves, so I decided to turn on my headlamp and start scanning,” Arteaga recalls. “That's when I saw the first one."

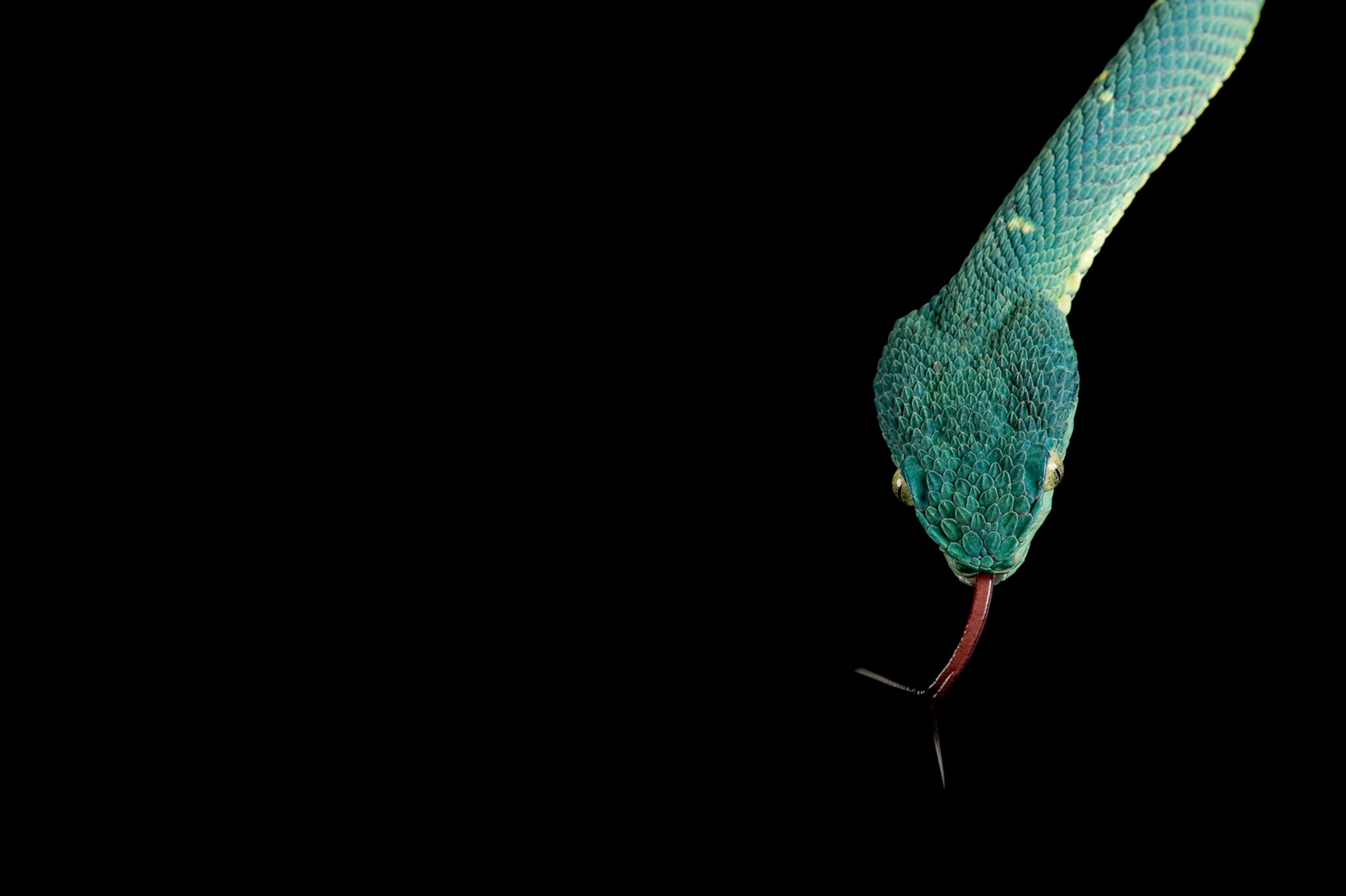

Gliding over the rain-drenched vegetation, Arteaga spotted a small, colorful snake. Its slender, pale yellow body was covered in rust-and-black splotches. Slate-blue eyes glared from its small head.

Later, Arteaga saw a second, similar snake and took the specimens back to the lab. After comparing the snake to known species and conducting extensive genetic testing, Arteaga confirmed that he had discovered a new species.

This creature would eventually be named Sibon bevridgelyi, and it’s one of five snail-eating snakes Arteaga and his conservation initiative Tropical Herping discovered on expeditions to Ecuador in 2013 and 2017. A paper outlining their findings was published today in the journal ZooKeys.

Although these snakes have just been discovered, Arteaga says four out of the five species are already at risk of extinction from deforestation and human encroachment.

Two Expeditions, Five Discoveries

To describe what they’d found, the team spent months counting scales and gathering measurements from more than 200 museum specimens, and extracted DNA from nearly 100 types of snakes, to compare against the newfound species.

All the new serpents belong to the genera Dipsas or Sibon, which are nonvenomous, tree-dwelling, snail-eating snakes found in South America.

Whereas other arboreal snakes feed on tree-dwelling mammals and birds, the small species Arteaga and his team discovered dine on snails and slugs. Their blunt snouts and flexible jaws are specially adapted for shoving into shells and sucking out snails.

When it strikes, a snail-sucking snake will seize the body of a snail with its long, delicate teeth. It will then begin to slurp the gastropod up, using its teeth to draw the snail from its shell as the lower jaw retracts. (Related: watch a snake rip its prey into pieces, rather than swallowing it whole.)

“The snake moves each part of the [teeth] inside the shell until it grasps more of the fleshy part,” Arteaga says. “This happens in a matter of minutes.”

There are currently 70 recognized species of snail-eaters, and they are among the most diverse groups of arboreal, or tree-dwelling, snakes. Experts say their unusual diet is an adaptation of their specific ecological niche in forests where snails are common.

The names of the snakes were auctioned off to raise funds for conservation. The two dubbed Dipsas bobridgelyi and Sibon bevridgelyi, after American ornithologist and conservationist Robert Ridgely and his late father Beverly, were found in the Ecuadoran dry forests.

Arteaga says his favorite snake from these expeditions is the blue-eyed S. bevridgelyi. “The first time I saw it, it was so different,” Arteaga says. “I thought this definitely had to be something new.”

Other snakes the team identified had red, black, or brown eyes.

The team found the snakes that would be later named Dipsas klebbai and Dipsas oswaldobaezi in the rain forests of Ecuador, and they’re named for patrons Casey Klebba and Oswaldo Báez. Also found in those forests, D. georgejetti was named after Rainforest Trust member and photographer George Jett.

Reaching the Public

The Amazon rain forest is so thick with biodiversity that a new species is discovered there roughly every other day. But destruction and degradation of rainforests drive extinction and threaten the plants and animals that live there.

Rather than naming the snakes themselves, the research team chose to auction the names to spread the word about these new species and make people more understanding of the threats they face.

“We realized that in general, there’s not a big connection between the science world” and the general public, says Lucas Bustamante, a biologist and photography director of Tropical Herping. The patrons who contributed to the auction simply discovered the conservation project and decided to support it.

All the money raised in the auction goes toward conservation efforts. The team used half the funds to purchase a 178-acre plot of land where two of the five species live, which the conservation nonprofit Fundación Jocotoco will add to the Buenaventura reserve. The other half will support scientific expeditions in Ecuador.

(The snake that eats toads to steal their poison)

Auctioning off snake names is not the team’s first foray at getting people interested in conservation. Nearly a decade ago, Bustamante and Arteaga co-founded Tropical Herping, an organization that melds photography, tourism, education, and research, to preserve tropical reptiles and amphibians.

“We are trying to do a different kind of science [that gets] more people get involved,” Bustamante says.