These invasive pests are tormenting Florida’s manatees

Armored catfish are driving manatees out of their warm-water refuges, putting their health at risk. Here’s why it’s happening—and what scientists are doing to help.

Winter mornings in Blue Spring State Park in Volusia County, Florida are silent except for the chirping of birds. Bald cypress trees loom, and the surrounding forested terrain is serene, reminiscent of an older Florida untouched by time. Cora Berchem’s paddle cuts deftly through the turquoise water. Her research canoe glides past large grey silhouettes of the spring’s manatees until she reaches a point where hundreds of them huddle together. The surface breaks to reveal a bulbous snout. A manatee has just come up to breathe.

Every winter, hundreds migrate to Blue Spring Run, a protected sanctuary. The park is a manatee mecca of sorts; they come to conserve energy, and keep warm in the 72-degree spring water. In 2024, over seven hundred manatees were observed in a single day. Berchem, Director of Multimedia and Manatee Research Associate at the nonprofit Save the Manatee, is on morning duty, observing the animals for injuries, health issues, or unrecorded offspring. The manatees drift languidly or rest at the bottom of the spring; mothers nuzzle their wriggly calves. From the surface, all seems calm.

But Berchem knows better. The manatees are being surveilled by droves of dark, spiny catfish that hover nearby, many latched on manatees' bodies. The inky coloring of the catfish is striking, they look like very dark shapes moving around the bottom of the spring run, with a prominent sailfin, a worm-like purple brown patterning and a flat belly well suited to grazing.

“We have seen up to twenty catfish on a single manatee. They're sitting on their heads or on their eyes, and you think about how uncomfortable that might be.” Berchem says.

Armored catfish—an invasive, two-foot-long bottom-dwelling species—came to Florida from South America in the 1950s by way of the aquarium trade and irresponsible owners who released the fish into the state's waterways. Generally, armored catfish are a successful fish that can travel overland during rain, expanding their presence. They have become impossible to eradicate.

(The Floridan aquifer: Why one of our rainiest states is worried about water)

With armored plating and suckermouths, the fish have a penchant for tormenting manatees. They aren't after the manatee, but rather the algae on its back which makes for a better meal than a slippery surface like an algal bed. They graze algae off a manatee’s back with bristle-like teeth, a sensation that’s disturbing and stressful for manatees. That causes behavioral and physiological changes among manatees at the spring, including excessive movement, leading them to drop to dangerously low body temperatures and weight.

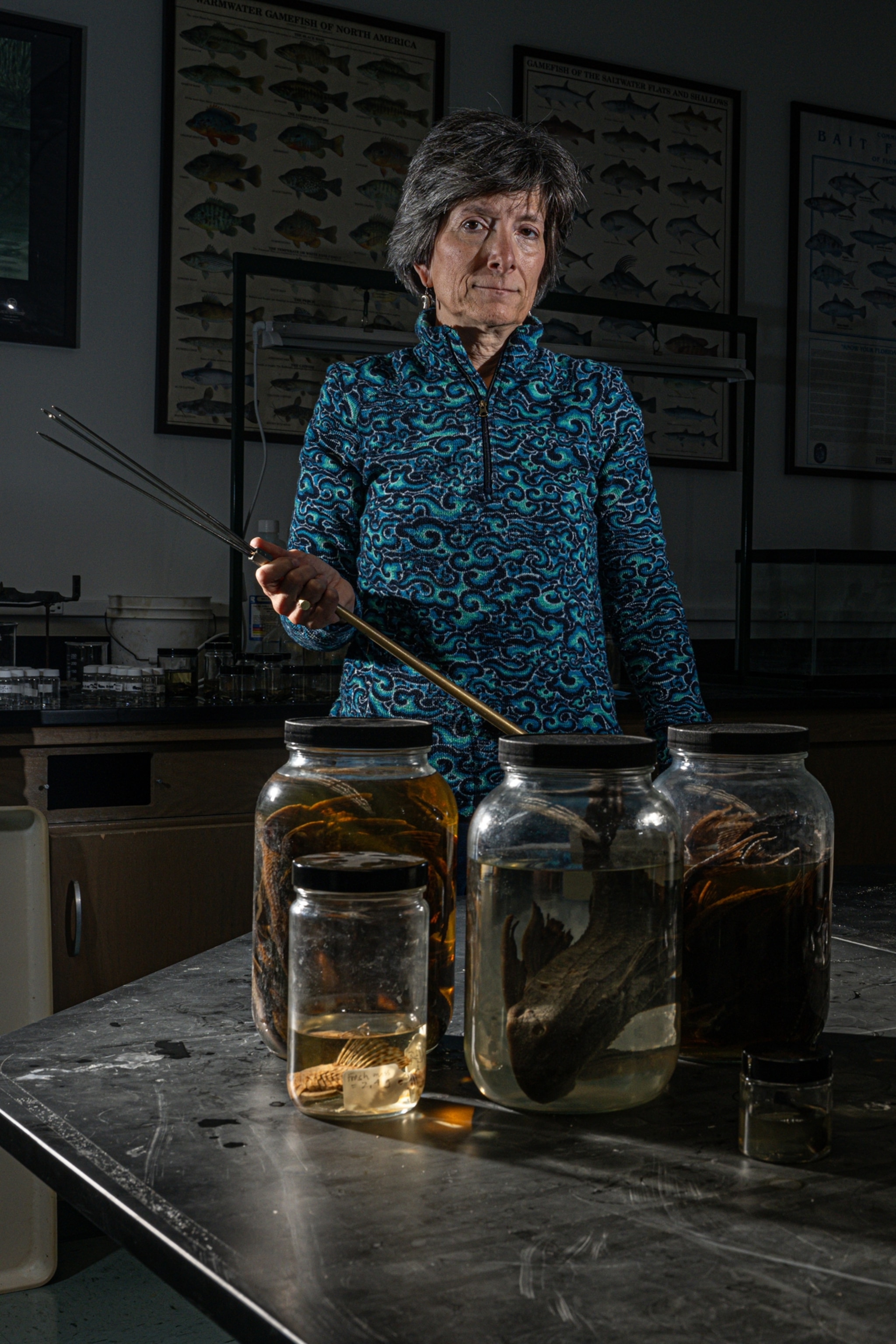

Melissa Gibbs, professor of Biology at Stetson University in DeLand, Florida, has been researching the impact on manatees. She found that manatees with attached catfish were significantly more physically active when they had catfish on them compared to when they didn’t, causing the manatees to needlessly expend energy required to deal with cold conditions, negatively impacting their health.

“Manatees will get twitchy and do a barrel roll, and the catfish dissipate. Then once the manatee settles down again, the catfish will also settle back down on that manatee. It really annoys them,” says Gibbs.

When manatees are in the spring run conserving their energy, there is nothing around for them to eat. As the catfish graze the algae growing on the manatees, they toss and turn, roll around, flip their tails, and swim more, burning off calories they need to preserve. Their metabolic rate spikes in response to the movement. Manatees then must leave the spring and venture back into the cold river to find food, which is where the real danger lies. Since the river is much colder, manatees are vulnerable to cold shock and stress due to their lack of blubber or insulating layers.

The catfish are a new stressor to an ever-growing list of issues that threaten manatees, including loss of habitat and food sources, boat strikes, and human interference. Manatees are currently threatened, but conservation groups are petitioning to relist them as endangered, leaving researchers desperate to find solutions.

Experts are looking for ways to help manatees cope

Just as generations of manatees have sought refuge in Florida’s network of springs, generations of armored catfish have too. Exterminating the catfish is nearly impossible because they’re too cunning and too entrenched. Berchem and Gibbs have both spearfished them, but the fish have adapted to hunting efforts.

Gibbs knew the fish were still lurking, even if they were absent when she was there to hunt. The evidence was catfish poop, abundant in the spring in the morning. Turns out, the catfish were leaving the spring run in the morning and coming back at night, as if they knew they wouldn’t be hunted.

Unable to eradicate the catfish, Gibbs suggests improving the quality of life for manatees so they will be better equipped to deal with the challenges that catfish create. Efforts include preserving and protecting warm water refuges, maintaining water levels to support high numbers of manatees, and maintaining speed zones, so manatees have enough time to get away from boats. Approximately 96 percent of manatees have scars from boat strikes, deep whitish gashes that heal and compound, heal and compound again, as years pass—permanent evidence of humanity’s carelessness.

Protecting and restoring seagrass beds, a primary food source for manatees, is also a priority. Many seagrass beds have been destroyed because of eutrophication, when nutrient runoff from land that seeps into seawater and causes harmful algal blooms, or a rapid growth of algae underwater. The blooms block sunlight from the seagrass, thus preventing photosynthesis and leading to the death of the seagrass beds.

The fewer external issues a manatee must contend with, the easier it is for them to cope with the catfish. Removal of trash and debris like fishing gear from natural spaces is one more key action to help protect manatees. One year at Blue Spring, says Berchem, a manatee got stuck in a bicycle tire. “We tried to catch him the whole season and he evaded us each time.” When he returned the next year, the tire had popped off and deep, seemingly engraved rings encircled his body.

Back on the water, Berchem spots a familiar figure. “This is Merlin,” she says, leaning over to identify a large male by the distinctive scar pattern on his back. Merlin is one of the oldest manatees at Blue Spring, according to Berchem. She says he’s been around since the 1970s when Jacques Cousteau came to the spring to film “The Forgotten Mermaids,” an episode of the famed oceanographer’s television show.

Berchem wonders about how the older manatees perceive the rapid environmental changes in their lifetimes. The world Cousteau captured fifty years ago is long gone, transformed in a time lapse of reduced springwater flow, algal blooms, nutrient overload, and urban sprawl. Manatees like Merlin have likely witnessed inexorable changes to their world, from disruptive boat traffic to the changing availability of vegetation, and the increased presence of invasive catfish in their waters.

The catfish, however, are here to stay. Though the coexistence is fraught, researchers are working to improve other aspects of manatees' lives and ultimately avoid a decline.

“I wonder about the kind of development that Merlin has witnessed over the last fifty years of his life,” muses Berchem. “It’s pretty stunning.”