The 30-foot sea cow quickly hunted to extinction because of its tasty meat

Few complete skeletons remain of this gentle behemoth, who was destroyed by explorers and fur traders in the Arctic.

On November 8, 1741, naturalist Georg Wilhelm Steller walked along the shores of an unnamed island. He had ended up in that desolate place as part of Vitus Bering’s expedition, whose goal was to discover a sea route from Siberia to America. The crew succeeded in their mission and reached the Alaskan coast — but on their return voyage, disaster struck. Their ship was wrecked, and they found themselves stranded on a barren, uninhabited island that they would later name Bering Island, in honor of their captain.

Steller was searching the coastline for driftwood, as their firewood supply was running low, and observing the island’s wildlife, stopping every now and then to jot down his notes in the small notebook he carried. Suddenly something caught the naturalist’s eye: a cluster of dark shapes was floating offshore. At first, Steller mistook them for drifting logs. But then he heard their snorting breaths and realized he was gazing upon a herd of immense, unknown marine creatures. Steller had encountered a new species: the gigantic sea cow that would be named for him.

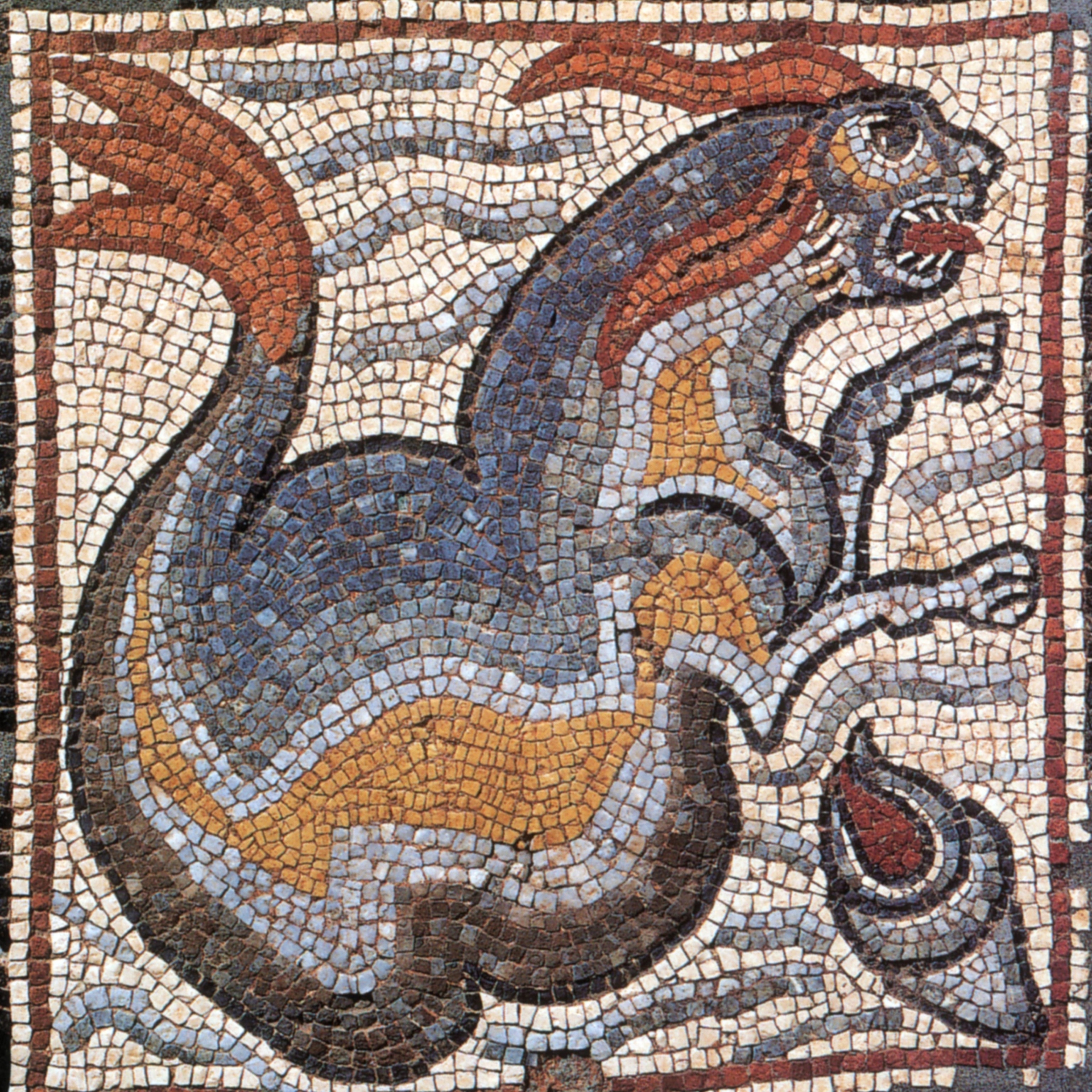

In ancient times, numerous species belonging to the order of sea cows swam in the world’s oceans. They were creatures of warm seas. Despite their rounded form, their layer of fat was thin, and they depended on temperate waters for survival. Yet one species swam against the current and began spreading northwards. It adapted to the cold waters by growing in size and developing a thicker layer of fat, eventually becoming a true giant among its kin: a fully grown sea cow is estimated to have reached up to 30 feet in length and weighed as much as 22,000 pounds.

The last Ice Age was the golden era of these Arctic sea cows. As ice sheets expanded, sea levels dropped, forming a chain of shallow bays filled with kelp forests, where herds of the Arctic sea cows grazed in abundance all along the Pacific coasts. When the Ice Age ended, conditions turned unfavorable for the species: rising sea levels fragmented the continuous stretches of kelp forests, and the herds became isolated from one another.

Archaeological evidence also shows that humans learned to use sea cows as a source of food. They were easy and tempting prey: one animal provided enough meat to feed an entire village. The slow-moving, gentle creatures were so easy to catch that the Aleuts dismissively called them “women’s game.” The sea cows’ numbers dwindled steadily until only a single population remained, living in the farthest reaches of the Aleutian archipelago. There, the last herd of Steller’s sea cows grazed untouched by hunters, until Captain Vitus Bering’s ill-fated expedition was wrecked upon their island.

For most of Bering’s crew, the enormous size of the sea cow was its main attraction, as their food supplies were nearly gone. Lacking the Aleuts’ expertise, however, they found hunting the animal was no easy task. Its body was covered in a thick hide, beneath which lay a layer of fat nearly eight inches deep. Even if a skilled marksman managed to hit the creature’s tiny, pebble-sized eye, the men faced another problem: how to haul the massive carcass ashore? Eventually they learned to harpoon the sea cows and, using ropes, dragged the gigantic bodies to land. When they at last secured their first catch, the men could scarcely believe their luck. The meat of a sea cow was flavorful, nourishing, and kept remarkably well. With its help, the crew survived the harsh winter on the barren island.

Steller now had a unique opportunity to study a species unknown to science. He devoted himself to the task with tireless zeal, though the conditions were far from ideal. In his report, he lamented the many misfortunes that hampered his work: “rain and cold, the tides, and the blue foxes that tore apart and carried off my tools—even my maps and ink.”

According to Steller’s account, the sea cows were highly social creatures. They cared for their young collectively, arranging the herd so that the calves swam safely at the center, encircled by adults. The bond between a mated pair, Steller observed, was profound: when one was wounded, the other would try to sever the harpoon line and often lingered in the shallows, searching for its partner long after its death.

On their island, the sea cows had no natural enemies, and they never learned to fear humans. Steller describes how, at high tide, the sea cows would drift so close to shore that he could wade among them and stroke their backs, while the men could row their boats right up alongside without causing the slightest alarm. They spent their days grazing and were discerning feeders, dining chiefly on kelp. Beyond observing their behavior, Steller also conducted detailed anatomical measurements and even prepared specimens of a calf’s skeleton and skin, though, to his great regret, he was never able to bring them back from the island.

Of the seventy-seven members of Bering’s crew, forty-six survived the nine long months stranded on the island. In time, they managed to build a new vessel from the wreckage of their ship. Steller departed the island elated, carrying with him the record of an extraordinary discovery; a new species he believed could rescue the impoverished Kamchatka Peninsula from famine.

News of the sea cow and its tender, flavorful meat spread swiftly. As fur traders began sailing from Siberia to the Alaskan coast, they made a habit of stopping at Bering Island to fill their barrels with sea cow meat. Having neither the time nor the need to master the art of harpooning, they shot and speared the animals in staggering numbers, trusting the waves to carry some of the carcasses ashore.

Meanwhile, the hunters drove the island’s sea otters to extinction. In their absence, sea urchins multiplied unchecked, devouring the kelp forests that once fringed the island. The sea cows now faced a double peril: the hunters’ guns and the loss of their sustenance. Slow to reproduce, their numbers collapsed, and within just twenty-seven years, the last known individual was gone. Thus, Steller’s brief account, written on that remote island, remains the only scientific record of this magnificent marine mammal.

The disappearance of the sea cows presented an intriguing puzzle to the naturalists of the age. Neither Steller nor his contemporaries possessed a concept of extinction. The men who encountered Steller’s sea cow conceived of nature as a divinely ordained and immutable order, created for humankind’s use and delight—a system whose structure lay beyond human power to alter. The idea that a species could vanish entirely from the great chain of being was, to them, inconceivable. Thus, the prevailing belief was that the sea cows had merely withdrawn to some distant island where they now grazed in peace, hidden from the hunters.

The disappearance of the sea cows only made the species more coveted. Now the fur traders gathered the scattered remains along the shores, packed them into barrels, and sold the bones to collectors for high prices. From these fragments, collectors assembled composite skeletons, often made up of bones from ten or more individuals. Only three to five complete skeletons composed of the bones of a single animal are known to exist, their scientific value beyond measure.

At the same time, the science of paleontology was advancing by leaps and bounds. Paleontologists astonished the public by unearthing the remains of extraordinary creatures—dinosaurs, mammoths, and pterosaurs—and, since the notion of extinction had yet to be conceived, history records a series of charming expeditions launched in hopes of finding them alive. Thomas Jefferson, for instance, organized and financed an expedition to the American frontier in search of mastodons. In time, however, it became clear that no Arctic elephants roamed the distant deserts of Arizona and, in 1813, the French anatomist Georges Cuvier gave voice to a startling idea: species could vanish from the earth forever. The concept of extinction was born.

This realization, however, did not yet lead to an understanding that extinction might also have befallen the sea cows. At first, extinction was seen as something confined to the distant past—a consequence of cataclysms such as the biblical Flood or a meteorite impact—and the notion that humankind itself could become such a catastrophe for another species was still difficult to conceive of or accept.

Yet the fate of the sea cow continued to stir heated debate. In the end, the matter was to be settled once and for all: In the 1780s the young scientist Martin Sauer was dispatched to survey the remote islands of the Bering Sea. After nearly a decade of study, he returned with a firm conclusion—the sea cows were gone, hunted into oblivion. His writings stand among the earliest scientific accounts of human-caused extinction. The fate of the sea cows thus played a pivotal role in awakening humankind—for the first time—to its own impact on the natural world.