‘Tiger King’ stars’ legal woes could transform cub-petting industry

Citing rotten food, separating young cubs from their mothers, missing animals, and fraud, court cases aim to end the most exploitive practices.

When Tim Stark fled Indiana in September, his life was crashing around him. The zoo owner, who appeared in the hit Netflix docuseries Tiger King, was losing his livelihood. His lions, tigers, bears, and dozens of other animals were being seized by authorities. He and his zoo owed hundreds of thousands of dollars in fines for animal welfare violations. He faced an arrest warrant for allegedly concealing animals set to be confiscated. Stark’s zoo, Wildlife in Need, which raked in millions with its baby tiger “playtime” sessions, had collapsed.

On the run, Stark railed against judges, officials, and animal rights activists in an hour-long, profanity-laced Facebook Live rant. He claimed they’d conspired to deny him his right to own and breed exotic animals. Taunting law enforcement, he brandished what appeared to be a hand grenade. “I am willing to die for what I believe in,” he said.

Three weeks later, he was arrested at a bed-and-breakfast in upstate New York and extradited to Indiana, where he faced a contempt charge in one county and a felony charge of intimidating a law enforcement officer in another.

Stark isn’t the only big cat owner from Tiger King embroiled in legal trouble. Many of the largest breeders and cub-petting attractions in the United States are also facing lawsuits or criminal charges.

While it’s legal to breed and exhibit big cats in the U.S. with proper licenses, Tiger King shined a spotlight on questionable conditions in a lucrative and lightly regulated industry. Now, a spate of court cases is challenging the legality of some standard practices, including pulling newborn cubs from their mothers and allowing tourists to cuddle, bottle-feed, and snap selfies with them. Lawsuits and prosecutions cite unsafe, unclean housing; poor nutrition; little or no veterinary care; illegally buying, selling, and shipping endangered species nationwide; and soliciting donations that allegedly benefit for-profit businesses. (The U.S. tiger trade puts both people and animals at risk.)

These civil and criminal court cases have the potential to overhaul the industry, says Brittany Peet, deputy general counsel at the nonprofit advocacy group People for Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA).

Thousands of captive tigers live in the U.S., mostly in roadside zoos like Stark’s. Experts say there are probably more in captivity in the U.S. than the 3,900 estimated to live in the wild across Asia. Threats to the world’s tigers go beyond animal welfare in cub-petting facilities. Trafficking in tiger bones and other body parts from captive facilities in China, Vietnam, and elsewhere in Asia fuels a lucrative black-market trade that is pushing wild tigers toward extinction. In the U.S., lax regulation has enabled the exploitation, suffering, and illegal trade of thousands of endangered big cats. The recent tide of legal action may be changing that.

Tiger King stars in court

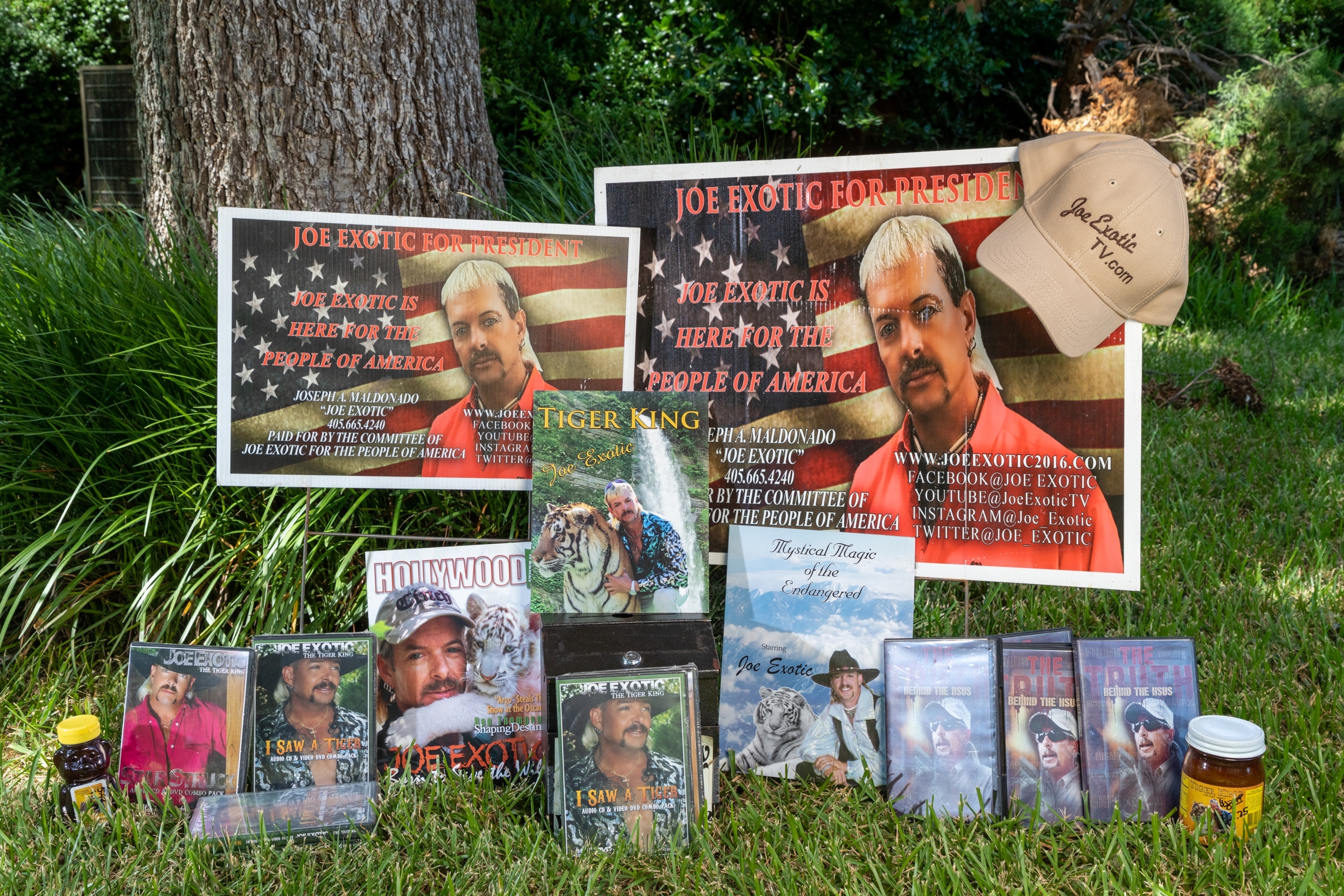

The strange drama portrayed in Tiger King put the tiger tourism industry on the radar, with 34 million viewers in the first 10 days after its release in March 2020. The series featured Joseph Maldonado-Passage—better known as Joe Exotic—and other big cat owners. Though they became eccentric cult figures to some viewers, others were shocked by what they saw: One clip showed a newborn tiger, still wet, dragged from its mother using a metal hook.

The Tiger King himself, who once ran the Greater Wynnewood Exotic Animal Park in Oklahoma, is currently serving 22 years in prison. He was convicted in 2019 of attempted murder-for-hire of big cat sanctuary owner Carole Baskin; of killing five tigers that were poor breeders; and of charges related to animal trafficking.

In August 2020, Exotic’s former business partner, Jeff Lowe, had his license to exhibit wildlife suspended by the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) for “grave” abuse and neglect. Then last November, the Department of Justice sued Lowe, his wife Lauren, and their businesses for allegedly violating animal welfare laws and the Endangered Species Act. In a text to National Geographic, Lowe called the charges “absolutely false...simply retribution.” In January this year, a judge ordered 14 of his tigers moved to a sanctuary because of “life-threatening conditions.”

Meanwhile, another zoo owner featured in Tiger King—Bhagavan “Doc” Antle, owner of Myrtle Beach Safari in South Carolina—was indicted last October on charges that include felony wildlife trafficking and misdemeanor animal cruelty. In an email last December, Antle denied “any act or conduct that could ever be considered ‘animal cruelty.’”

These and other court cases have exposed exploitation and abuse in the big cat cub petting industry, most of it hidden from visitors who pay to spend time with cubs. Big cats are subject to factory-like breeding to produce a constant supply of cubs, and few visitors realize that many of them die young. Those that survive are too big and dangerous to pet by the age of 12 weeks, USDA regulations say. Those cubs usually are then sold off to other facilities, dumped, or simply disappear.

Nothing left to lose

Court documents and inspection reports reveal how bad things were at Stark’s Wildlife in Need zoo for years before it was shut down. Stark sometimes blocked mandatory inspections, swearing at government officials. From 2012 to 2016, USDA inspectors cited more than 120 violations of the Animal Welfare Act.

Stark fed animals expired meat and roadkill, and left them with green water squirming with larvae, according to the USDA citations. The cats lived in small enclosures strewn with dangerous debris and their own feces, without shelter from sun or snow. Sick or injured animals went unexamined; many died. Stark testified that he “euthanized” a sick and injured young leopard with a baseball bat in 2012.

Animals regularly arrived and disappeared without legally required paperwork. During one inspection, officials discovered 43 previously undocumented animals on site; and couldn’t find another six that were supposed to be there.

Furthermore, inspectors found flimsy animal enclosures that they say posed “significant risk” to the public. During hands-on encounters, tiger cubs bit and scratched customers and ran uncontrolled. In 2013, a neighbor shot a leopard that was roaming free. Stark denied it was his.

Despite citing Wildlife in Need for numerous violations over the years, the USDA automatically renewed Stark’s license annually, per its standard policy. Finally, in February 2020, the department revoked it. A judge fined him $40,000 and Wildlife in Need $300,000.

Though the USDA took action in this case, the department has been under fire for years for weak enforcement of the Animal Welfare Act, which advocates say sets bare minimum care standards. Cathy Liss, president of the D.C.-based nonprofit Animal Welfare Institute, says enforcement got even weaker under the Trump administration: There was a 93 percent drop in fines and license suspensions, from 239 in 2016 to 17 in 2019.

It remains to be seen how aggressively the USDA under President Joe Biden will enforce the Animal Welfare Act. In an email, a spokesperson for Secretary of Agriculture Tom Vilsack, who served in the same position in the Obama administration, said that “USDA will make full use of its enforcement authorities to ensure the humane care and treatment of animals...covered under the AWA.”

In court for animal abuse

Carney Anne Nasser, an attorney specializing in animal law, says that a high-profile PETA lawsuit filed against Stark in 2017 was what likely prompted the USDA to act. PETA alleged that Stark’s treatment of cubs violated the Endangered Species Act, which makes it illegal to harm or harass federally protected species, including tigers.

PETA has successfully sued several roadside zoos under the ESA, with judges explicitly acknowledging that the law applies to animals in captivity as well as in the wild.

It’s important for people to realize that these [attractions] can be fronts for profitable animal abuse industries.

Curtis Hill, Former Indiana attorney general

The group’s case against Dade City’s Wild Things was among its most significant wins against the cub-petting industry, Peet says. The Florida cub-petting venue mass-bred and traded tigers, and threw cubs into a chlorinated pool for $200 “swim with tigers” encounters. PETA won the case in March 2020 after the judge found that owner Kathy Stearns and her son Randall Stearns violated a court order not to move their cats: In 2017, they had shipped 19 cats to Joe Exotic in a cattle trailer without air conditioning or water in the July heat. A tigress gave birth during the 1,200-mile journey; all three cubs died. The Stearns family was banned permanently from owning tigers, and Kathy Stearns still faces criminal charges in Florida for allegedly siphoning nonprofit funds to pay personal expenses.

PETA’s case against Dade City’s Wild Things set an important precedent. “It was the first federal ruling that prematurely separating [tiger] cubs from mothers, using them in public encounters, and confining them in inadequate conditions violates the Endangered Species Act,” Peet says.

Several months later, another judge rendered the same opinion in PETA’s case against Stark, further strengthening the precedent and expanding it to include lions and lion-tiger hybrids. The judge wrote in his decision that these practices cause “serious harm, in many cases a deadly one.” He further ruled that declawing big cats, which involves amputating part of their paws, violates the Endangered Species Act.

Pseudosanctuaries

Owners of cub petting attractions are also under scrutiny for financial dealings.

While investigating Wildlife in Need’s finances, the state of Indiana said it identified “wire transfers totaling hundreds of thousands of dollars from [Wildlife in Need]’s bank accounts to known and/or suspected animal dealers,” according to a motion it filed last July.

On April 7, 2021, the judge in that case found that Stark illegally used donations to Wildlife in Need—a nonprofit founded in 1999 to “rescue, rehab and return indigenous species to the wild”—to buy animals and to pay for personal expenses such as meals, gas, utilities.

Contributors “were duped,” Indiana’s then-Attorney General Curtis Hill said last year. “It’s important for people to realize that these [attractions] can be fronts for profitable animal abuse industries.”

Stark was ordered to repay the money, and he is permanently barred from owning animals.

Many roadside zoos are registered as nonprofit “rescues” or “sanctuaries,” a status that confers tax breaks and allows them to solicit donations. But few meet the criteria, says Lisa Wathne, who oversees captive wildlife protection at the Humane Society of the United States, a Washington, D.C.-based nonprofit.

A true sanctuary never breeds, buys, sells, or trades animals, she says. It keeps them for life and provides proper food, housing, and veterinary care. Most in the U.S. are accredited by the Global Federation of Sanctuaries. Anything else is a “pseudosanctuary,” she says.

Doc Antle straddles both worlds. At the for-profit Myrtle Beach Safari, visitors buy tour packages to interact with “animal ambassadors,” including tiger cubs and wolf pups. His nonprofit Rare Species Fund collects donations for, among other things, “education of the public about conservation issues through ambassador animals.” Over a period of five years, from 2014 through 2018, the nonprofit spent more than a million dollars in donations—a yearly average of $210,000—on animal food, care, and enclosures, according to an analysis of its federal tax forms. Those expenses account for more than two-thirds of its total spending. The other third, about $100,000 a year on average, was given away in grants to other organizations.

Antle did not respond to a request for comment about the nonprofit’s finances.

Nasser says that prosecuting financial fraud “will put a nail in the coffin for roadside zoos. With the cost of feeding a tiger up to $7,000 per year, many could not stay in business without fraudulently taking donations.”

Meanwhile, these captive cats have no conservation value—they’ll never be released into the wild or used to shore up wild populations. “If wild tigers became so scarce that we needed to use captive-bred stock, we would use animals from accredited captive breeding programs, not the inbred, hybrid, unhealthy cats from a roadside zoo,” says John Goodrich, tiger program director at Panthera, a New York-based conservation organization.

Confiscated animals

When Stark lost the PETA lawsuit in August 2020, the judge ordered him to surrender his remaining 22 tigers, lions, and tiger-lion hybrids, as well as four lion cubs he’d illegally sent to Jeff Lowe in 2019. The same month, the judge in Stark’s fraud case ordered that the rest of his animals be placed in temporary custody.

On September 11, under the protection of some 50 police and federal marshals, the Indianapolis Zoo began removing 161 animals. When 23 animals couldn’t be found, the state accused Stark of hiding them and a judge ordered his arrest. That’s when Stark went on the run.

Several days later, PETA removed the big cats. Some were so thin that every rib was visible, Peet says. One lion was unresponsive; another crippled. The cats went to two accredited sanctuaries, Turpentine Creek Wildlife Refuge in Arkansas and the Wild Animal Sanctuary in Colorado.

When Pat Craig, founder of the Wild Animal Sanctuary, drove to Oklahoma to pick up lion cubs Stark had sent Lowe, there were only three. One had died several weeks earlier, PETA learned. The others “were in horrific shape,” small and underweight, Craig says. Nala, a female, could only take a few steps without falling over. X-rays revealed multiple untreated leg fractures, a result of metabolic bone disease caused by poor diet. With proper feeding and veterinary care, Nala’s fractures have healed, Craig says, and she’s expected to survive.

The United States of America vs. the Lowes

The legal landscape for the cub-petting industry is changing, case by case, but the federal lawsuit filed in November against Jeff Lowe, his wife Lauren, and their businesses potentially carries the greatest weight.

The Department of Justice typically doesn’t litigate animal welfare cases. They took this one because Lowe publicly flaunted the law, says Jonathan Brightbill, the DOJ attorney arguing the case. He who called Lowe’s actions “a very aggressive form of evasion.”

After USDA suspended Lowe’s license to exhibit wildlife in August, Lowe surrendered it permanently to avoid government oversight, the DOJ says. Soon the Lowes began using their new “Tiger King Park” as a private film set. But “exhibiting” animals on TV and social media still requires a USDA license, says Delcianna Winders, an animal rights lawyer who directs Lewis & Clark Law School’s Animal Law Litigation Clinic in Portland, Oregon. (The Lowes’ new venture raises concerns about the future of “digital” animal exploitation.)

The DOJ’s complaint “includes 110 pages of evidence detailing some of the most extreme abuse and neglect of big cats and primates that I’ve ever seen documented,” Nasser says. “The case against the Lowes marks the most aggressive civil enforcement action against an animal exhibitor in the history of the Animal Welfare Act.”

Among the largest tiger breeders, the Lowes will no longer be able to own or exhibit endangered species if they lose the case.

The future of tiger cub selfies

The cases against the Tiger King’s cat owners have already affected the cub-petting industry. At his peak, Joe Exotic claimed to own more than 200 tigers. Hundreds of cats flowed through Tim Stark’s zoo. Both are shuttered. And Antle and Lowe’s fates will soon be decided in court.

Congress is also stepping in. The nation’s first federal bill regulating big cat ownership was reintroduced to Congress in January. The Big Cat Public Safety Act would prohibit private ownership of big cats as pets and ban cub-petting. Another bill, the Animal Welfare Enforcement Improvement Act, would tighten licensing rules and compel stronger enforcement of animal welfare laws. It would also allow citizens to sue exhibitors for abuse under the Animal Welfare Act. It has not been reintroduced in the current Congress.

The situation has changed dramatically from a decade ago when you could buy a cub for a pet or snap selfies with cubs at flea markets, county fairs, or malls, Winders says, and more changes are likely to be coming.

These legal actions against zoo owners “put the writing on the wall” for the industry, she says. “These cases have established that the cruelty inherent in cub petting operations is illegal.”

Wildlife Watch is an investigative reporting project between National Geographic Society and National Geographic Partners focusing on wildlife crime and exploitation. Read more Wildlife Watch stories here, and learn more about National Geographic Society’s nonprofit mission at natgeo.com/impact. Send tips, feedback, and story ideas to NGP.WildlifeWatch@natgeo.com.