Venus Flytraps Have Surprising Pollinators ... and They Don't Eat Them

Researchers have identified which species are responsible for pollinating the carnivorous plants, but it's unclear why the plants don't eat them.

Out of the more than 600 species of carnivorous plants, the Venus flytrap is one of the most iconic. The arthropod assassins are known to dine on insects to supplement the few nutrients they get from their soil. While other carnivorous plants can be found worldwide, the vulnerable Venus flytraps are restricted to a small patch of subtropical wetlands in the U.S. Carolinas.

Researchers have been examining some parts of the plants for years, but other traits have gone unexplored.

"Basically, almost all that research is focused purely on the snap traps," says Clyde Sorenson, an entomology professor at North Carolina State University. "As charismatic as the plant is, nobody ever knew who pollinated it."

Or, at least, no one knew the plant's pollinators until now. Along with his colleagues at NC State, Sorenson is a co-author of a paper digging into what insects pollinate Venus flytraps in their native habitat. The researchers found that out of the scores of insects and spiders that become flytrap meals, only three species are common at the flowers and carry lots of flytrap pollen.

The study, published this week in the journal American Naturalist, marks the first time researchers have investigated the pollinators of these plants.

Digging into Plant Diets

Four times over the course of a five-week flowering season, the team visited a 100-mile-radius plot in Wilmington, North Carolina, where Venus flytraps are natively found. They used nets to collect bugs on and in the flowers, and traps to catch spiders.

The predatory leaves of Venus flytraps are separate from their flowers. The flowers have bright green centers and white petals with green lines. They adorn the tops of tall stalks that extend beyond the leaves, which prevents pollinators from being trapped and eaten by the plant. (Venus flytraps also have fruit, which comes in the form of round, green pods containing shiny black seeds.)

The leaves, however, are lined with short, stiff sensory hairs that tell the plant to snap shut when something touches them. It might take a few seconds for the plant to close at first, but the total snapping action can happen in less than a second, trapping tasty insects inside.

When the trap closes, it constricts tightly around the insect. The finger-like cilia that line the tops of the leaves lace together, forming an air-tight seal so the plant's digestive fluids don't leak out and bacteria can't get in. The digestion process for dissolving trapped insects can take several days.

Elsa Youngsteadt, a research associate and lead author on the paper, spent some time opening more than 200 flytrap stomachs to find the insect remnants dissolving inside. Sometimes, the crawlers were so thoroughly digested that their species was initially unrecognizable.

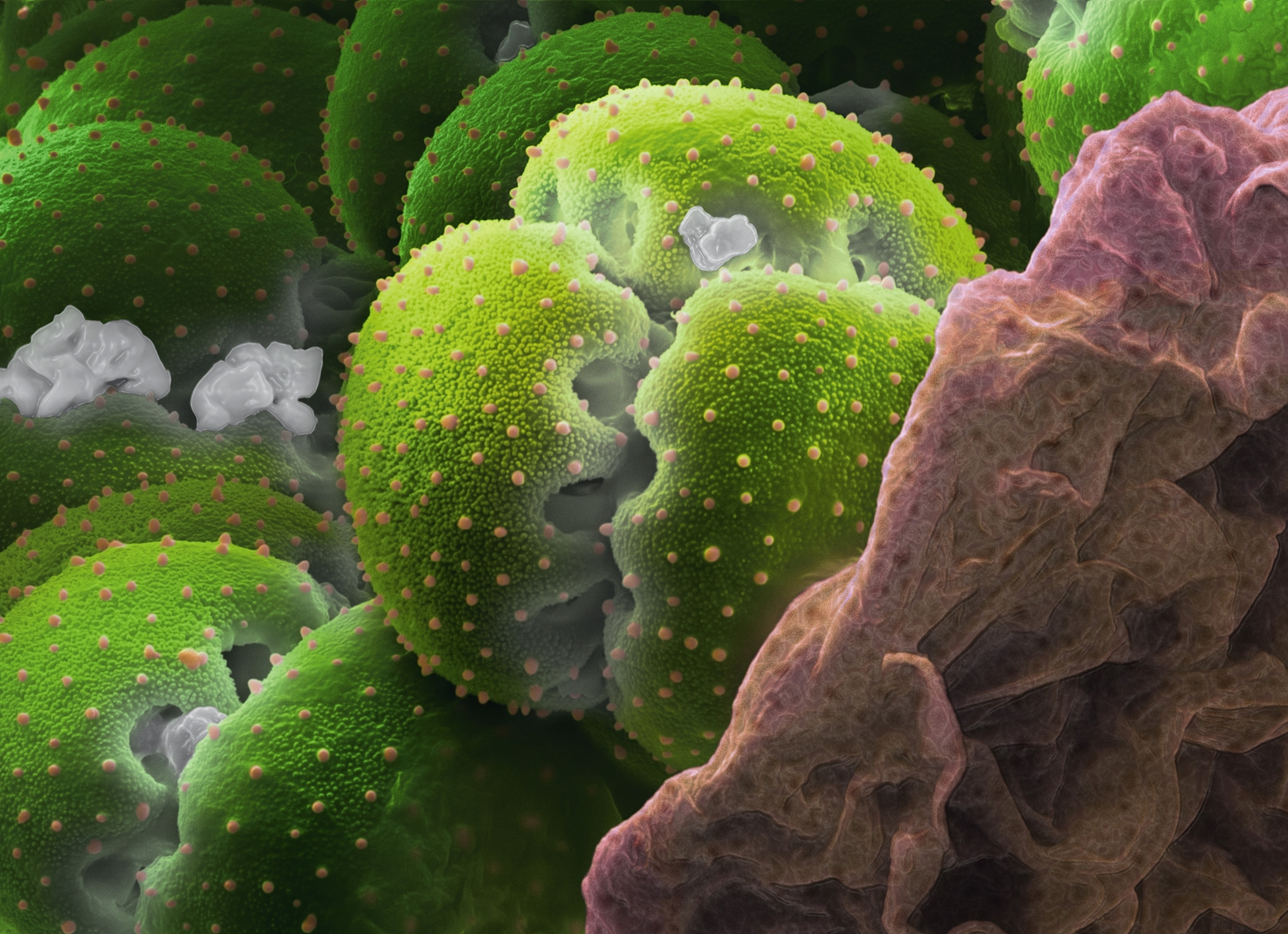

After collection, the half-eaten insects and spiders were brought back to the lab. The researchers then removed pollen from them to make sure it actually did belong to the flytraps. Venus flytrap pollen is about 10 times larger than other pollen in this ecosystem, and has four lobes. Youngsteadt says, "it looks like something out of a video game."

Of the roughly 100 different species that visited the plants, only a few were effective pollinators. These included green sweat bees, checkered beetles, and notch-tipped flower longhorn beetles, all of which were found on the plants but not in their traps. Beetles are not generally the type of insects you might think of as pollinators—normally, bees come to mind—but as it turns out, they are particularly important for this species. (Related: See how bombardier beetles avoid being eaten by toads.)

"That was pretty remarkable," Sorenson says. "We did not expect to catch a lot [of live samples], period."

Picky Eaters

The study results could help researchers figure out basic aspects about the iconic plant. Now that the researchers know what insects pollinate Venus flytraps in their natural habitat, the next step is trying to figure out why the plants don't prey on these insects. (Related: "This Cockroach May Pollinate Flowers—Extremely Rare Find")

The pollinating insects might be spared because of the architecture of the plant. Venus flytrap flowers are located high up on stems far above the traps. The pollinating species might just be flying above the "danger zone," of the plant, flitting from flower to flower. But although some of the pollinating insects are transporting pollen, a lot of them are actually eating it.

"What we don't know is how good those insects are at transferring the pollen back to the [plants] themselves," says co-author Rebecca Irwin, an NC State ecology professor.

The color of the flytraps might also have something to do with which pollinators they attract. Their snap traps can range from green to red, and the researchers say these different shades could lure in different prey species. It's also possible that the flytraps emit certain scents or chemicals that attract pollinators or prey.

Moving forward, the researchers will continue efforts to explore why Venus flytraps don't bite the bugs that pollinate them. (Read: "9 Ways You Can Help Bees and Other Pollinators At Home")

Future Conservation Efforts

Youngsteadt says this study may not have any immediate implications for conservation, but Venus flytraps are still an at-risk species. Even within their limited East Coast ecosystem, the plants are threatened by encroaching development where humans are draining their bog habitats for land use.

Venus flytraps are also poached and sold as pets in larger markets. There are currently more Venus flytraps popping up in pots than there are sprouting in their natural environment.

"It may need some more focused conservation management in the future," Youngsteadt says. "Knowing pollinators is part of knowing that story of what the plant needs to continue thriving."

A previous version of this story said all the pollinating insects were beetles; two of them are beetles, and one is a bee. The story has been updated.