How the World's Youngest Nation Descended Into Bloody Civil War

Fighting between its two main tribal groups threatens to tear South Sudan apart.

NASIR, South Sudan—When she was a girl, in the 1960s, Sarah Kier's parents fled southern Sudan with her. The Sudanese civil war, in which black-African inhabitants from the country's south were fighting for autonomy against an oppressive Arab-dominated government in the north, had been going on, without respite, for more than a decade. Kier's family moved to the hills of western Ethiopia. When she grew older, Kier became aware of the south's struggle. She joined the southern rebel militia, the Sudanese People's Liberation Army (SPLA), and became a battlefield medic. She spent much of her early life around violence and death.

On a hazy afternoon this past April, Kier was in the passenger seat of an old Land Cruiser, moving through those same hills, thinking about what it was like to not have a childhood. "You know, like for a young person somewhere else, you go for disco," she told me. "We don't know that. We [Sudanese] have ever lived with guns, from the word go."

The road emerged from a forest into a valley, and Kier gasped and smiled—as a girl, she suddenly recalled, she had lived in a house near here. It seemed a lifetime away. Then she noticed that trees had been cut down to make way for farms. She shook her head and clucked her tongue. "I'm telling you, this is sad," she said, looking out the window. "I mean, I am connected to those trees."

That morning Kier had departed in the Land Cruiser from Addis Ababa, the Ethiopian capital, where for weeks she'd been living in a small, bare room in a guesthouse, along with South Sudanese friends. They were living in exile, watching from afar as their country, less than three years old, disintegrated.

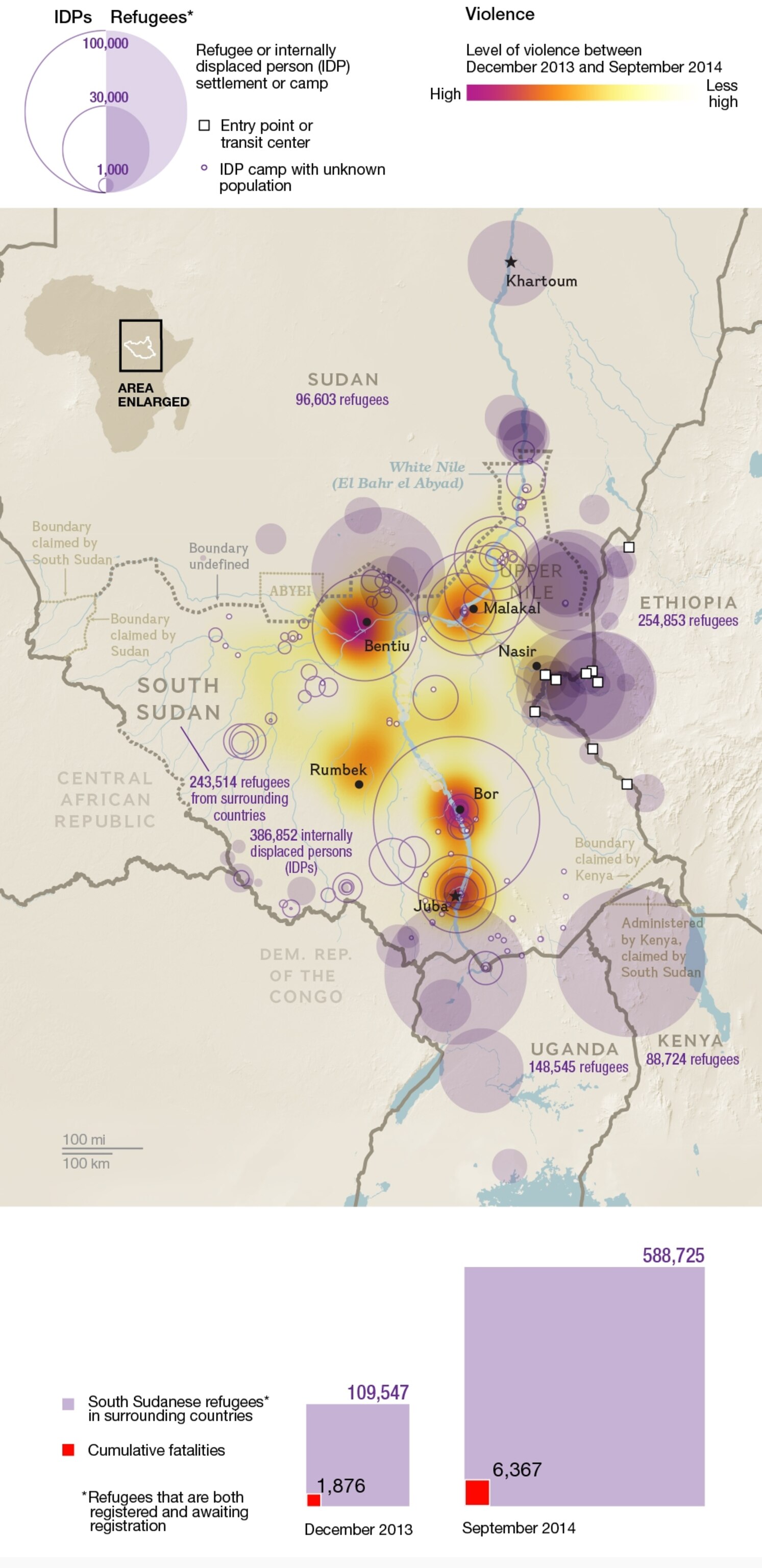

The civil war that had driven her family out had continued, off and on, until 2011, when the south finally gained independence. The creation of the Republic of South Sudan, in July of that year, was the most jubilant scene of African progress since the end of apartheid in South Africa. But in December 2013, the violence returned. Pitted against each other were South Sudan's two predominant and most populous tribes, the Dinka and Nuer. Longtime rivals who had battled over land and resources since at least the 19th century, their fragile détente underlay the new republic. Without it, there could be no South Sudan. And now, faster than would have seemed possible—so fast it seemed somehow fated—they were once more at one another's throats.

A Nation Unraveling

As thousands died and hundreds of thousands were displaced, South Sudan's president, Salva Kiir, who is Dinka, claimed the conflict had originated in a coup attempt, and laid the blame for it at the feet of his former vice president, Riek Machar. Machar, a Nuer, leveled damning accusations of his own: Kiir had not only fabricated the coup plot in order to kill him, Machar declared, but also had in mind a genocide of the Nuer. Machar fled the capital, Juba, for his seat of power, in the country's northeast, and arranged a rebellion (likewise with improbable speed), and battles and atrocities followed.

This all came as a shock to the outside world, still gazing on its youngest nation with pride. The shock was particularly keen in Washington, the main foreign cheerleader for, and funder of, South Sudanese independence. In May, Secretary of State John Kerry was dispatched to bring Kiir and Machar to the negotiating table; the ceasefire he brokered lasted a matter of days.

The South Sudanese themselves were less surprised.

A Bad Thing Long Ago

Sarah Kier was on her way to the village of Nasir, in the Upper Nile Province of South Sudan, the heart of Nuerland and Machar's headquarters, with a soldier and a bodyguard. She was a veteran of the civil war, and after independence had been appointed a minister in Kiir's government; but when the fighting broke out in December, she was targeted by his troops—because she's part Nuer, she believes. (Her father is Nuer, her mother Dinka.) She joined Machar's insurgency, and went to Addis Ababa, where members of his inner circle had gathered to lobby the Ethiopian government and outside world for support.

Kier and her companions planned to sneak over the border at the Baro River and had agreed to bring me with them to meet Machar. (Kiir's office had declined my request to speak with him.) On top of the Land Cruiser were jerricans of oil, sacks of rice, supplies, and messages destined for his camp, where she was to take part in a meeting of his generals. Their forces had been stopped outside Juba and pushed back. The war had stalemated. Kier hoped to convince Machar to put her in charge of one of the theaters of battle.

Even before the conflict began, Machar was the most controversial of South Sudanese public figures, considered by some a selfless patriot, by others a shameless traitor. He is in many ways the embodiment of South Sudan's war within, the principal harbinger of what the historian Francis Deng has called his country's culture of "ritualized rebellion." And Kier, who is unmistakably South Sudanese in appearance—very tall, very dark—could not have been prouder to be in his orbit. A phone at each ear, the mother of seven talked excitedly of returning to the battlefield. "I'm going to war, I'm going to war, my dear," she said to a friend on a phone. "I'm going to shoot my own gun." She referred to Machar as Dr. Riek, or The Big Man. "We will talk to The Big Man when we get there," she said, when I asked whether he knew a National Geographic reporter was coming with her.

She recounted how she had gotten out of Juba when the fighting began. An old friend and fellow soldier called. "He told me, 'Leave your house now,'" she said in a rapid-fire patter. "I told him, 'Give me a gun. Me, I will not die. Give me a gun. I will not die like this.'" Four months later, she still couldn't believe what happened. "Could this be one of those bad dreams, when you wake, you say, 'Oh, God, thank you, it was a dream'? Because we thought we're just now coming to enjoy our country."

Riu, the soldier, a tall, rangy Nuer in his early 30s, was squeezed into the cargo hold in the back of the truck, a green patrol cap pulled over his forehead. He was more solemn than Kier. When the fighting began, he said, he was in his barracks in a village outside Juba. "Everyone is just firing his gun and shooting at each other." He escaped and made his way to the capital, where he found a group of soldiers who were secreting Machar and other officials out of the city. He joined them. "What took place on that day was something planned."

As they talked, Kier grew agitated. How had their homeland descended with such ease into suicide? she wanted to know. How had their country, whose creation had given the world so much hope, turned so quickly on itself? "Children have been killed. Innocent ones. Innocent blood," she said. "For what? Because of the tribe? A tribe is not by choice." Riu calmly mused on this. "I can just conclude," he offered, "that Dinkas are having some kind of leadership style that easily leads people into chaos."

That afternoon the air grew thick, the landscape mountainous, and the conversation turned to the supernatural. Kier and her companions considered themselves to be good Christians, as many South Sudanese do. But they were struggling to reconcile that with what they'd seen.

"What happened in South Sudan," Kier said, "I think even God wouldn't have allowed it, because the sin is too much."

"God is punishing South Sudan," said Jacob, the bodyguard, who compared his land to Israel. "I think they've done a bad thing long ago."

Kier nodded. "God can punish a whole nation because of one person," she added, seeming to have Salva Kiir in mind. "Just like God also can save the whole nation because of one person." She seemed to have Machar in mind.

I asked Riu what he thought of this. "I think it is just some kind of illusion, when you talk of South Sudan being punished by God," he said. "All of these disasters, or political conflicts, they happen as a result of many things."

In every town in which they stopped in Ethiopia, they met friends who'd fled South Sudan. (Most were Nuer, as was clear from the horizontal gaar scarring on their foreheads.) They hugged and laughed, happy to see each other alive. Some were coming from Nasir, in South Sudan; others were on their way there. But most, it seemed, were living in squalid roadside hotels, waiting to see what would happen. How long they would have to live in exile, none knew. If it was for the rest of their lives, it wouldn't be the first time they had faced the prospect.

Ritualized Rebellion

There is a popular local proverb: "When God made Sudan, he laughed."

More than any other part of Africa, the Sudan is defined by civil war. It was ruled by the Ottoman Empire, then ushered into the 20th century by an invidious arrangement of Egyptian and British control. Colonial efforts at modernization, such as they existed, were confined to the north; the south was, in the words of one historian, "a mere field from which slaves were harvested."

Though the British favored the Nuer, venerating their virile warrior culture and relying on them to keep the Dinka and other tribes (roughly 60 in all) in check, the Arab ruling class left in place made no secret of its scorn for the black southerners. The southerners, in turn, with their mixture of traditional faiths and Christianity, did not hide their unwillingness to be dictated to or converted to Islam, even if resistance meant their death.

In 1955, months before Sudan gained its independence, the southerners began a war for liberation. It lasted 17 years. The Sudanese military bombed and razed villages across the south and killed, raped, and enslaved civilians en masse. Juba was put to the torch. A period of peace followed in the 1970s. But in 1983 the southern cause gelled into the Sudan People's Liberation Movement (SPLM) and its military wing, the SPLA. Soon after, an Islamist military junta took over in Khartoum. Subjugation of the south was foremost on its mind, even—in fact, especially—if it meant killing people. The abuse was redoubled.

The Second Sudanese Civil War, as it is now known, lasted from 1983 to 2005—the longest war, anywhere, of the modern era. It's estimated that by the end of these two wars, some 2.5 million people, the equivalent of more than a fifth of the current population, had died in fighting or resulting displacement, famine, or disease. Many thousands of others, like Kier and her parents, fled to neighboring countries and the West.

Alongside the civil war raged southern fratricidal conflicts. The most bitter fighting was between Dinka and Nuer factions. But in the push to independence, their rivalry, like the rest of the south's internal fissures, was ignored or played down. Once South Sudan existed, went the thinking, all wrongs could be righted. Scholars pointed out that a similar myopia had proved disastrous to the African independence movements of the 20th century, not least Sudan's. "The ground upon which the country landed at the time of independence was already cracking underneath," as Jok Madut Jok, a historian and former undersecretary for culture and heritage in Kiir's government, put it to me. Amid the elation of 2011, however, cautionary voices like his were drowned out.

Nothing Is Happening

At the Baro River, which forms part of the border between Ethiopia and South Sudan, we loaded the sacks and boxes into a motorboat piloted by a small boy. A minute later, we were in South Sudan. Once atop the steep bank, we found a band of young men in jeans, shorts, and soccer jerseys, Kalashnikovs slung on their backs. They were fighters with the White Army, a Nuer militia allied with Machar. It is known for killing Dinkas, arming minors, and looting anyone and anything with equal abandon.

After an hour, a muddied Chevy Suburban pulled up. From it stepped two men who introduced themselves as colonels in the Sudan People's Liberation Movement in Opposition, Machar's breakaway party. On the drive to Nasir to meet Machar, we passed men walking with rifles and field blankets, their gaits slow with fatigue. A colonel explained that they were coming from the city of Malakal, two days' march, where Machar's troops and the White Army were battling Kiir's government forces for control. "Malakal has changed hands four times," he said.

In Nasir, which still had the steamy, forlorn atmosphere of the British cattle outpost it once was, an easy transition to rebel life was being effected. On the wall in the county commissioner's office hung portraits of Machar and Kiir. Kiir's face had been scratched out with a black pen. In the market square, community meetings and civil trials were being conducted. In one trial, two White Army insurgents, an uncle and nephew, were in dispute over a truck. They'd won the vehicle when they'd killed the government soldier who was driving it. The nephew's claim to it was that he, unlike the uncle, knew how to drive; the uncle's claim was that he had fired the gun.

Machar's camp, on the edge of the town, was small and simple: several tukuls, the traditional Sudanese circular huts, arranged around a dirt clearing. Heat-shimmered scrub brush and sorghum fields stretched in every direction. Between a large tree and a flagpole was a wood-paneled coffee table covered with laptop computers, books, notepads, and satellite phones.

A soldier with a spear stood at attention behind the table; another crouched in front of it manning a .50-caliber field gun, discreetly picking at his toes. At the table, between the sentries, in a black pleather desk chair, was Machar. Even seated he was immense: six-and-a-half feet tall and more than 300 pounds. He wore forest camouflage, eyeglasses, a gold watch, and high-top black sneakers. A tuft of receding hair was flecked with gray, as was his goatee. A soldier fumbled around him with a knot of power strips and adapters, while Machar held a satellite phone to his ear, occasionally talking softly, shifting among English, Nuer, and Arabic.

Finally he put the phone down and gazed up with small, squinting eyes and the rumor of a smile. It was clear he hadn't known, or hadn't remembered, or hadn't cared, that we were coming. He listened patiently and uninterestedly as Kier told the story of her escape from Juba. Then he asked if she knew about the fate of his home there. It had been ransacked and destroyed by government forces, she had heard.

"The first thing they took was the cars," she said.

"The best loot to them was the cars?" Machar said. "What about my books? And the archives?"

"I don't know," she said.

"That is better loot," he said, with a moan, as though to suggest that his tormentors hadn't even sense enough to properly steal from him. "Salva Kiir and his cronies. Well."

Machar welcomed me with the understated amiability for which he's well known. "There was no coup. It was an assassination attempt. Eleven days I was on the run, being hunted," he said. "Our fight is against a dictatorship. Salva Kiir wants to create a dictatorship out of this new country. And we're saying no."

As he spoke, he picked up one of the books from the coffee table and leafed through it languidly. I noticed the cover: Why Nations Fail.

I asked about the state of his rebellion. "These are the three activities: either fighting, or mobilization, or—" he motioned to indicate the inactivity around us and chuckled, "nothing is happening."

"I Am Part of the Gods"

Riek Machar has been called the Bill Clinton of Sudan. The journalist Deborah Scroggins describes him as a man of "bottomless ego" who "feels your pain even as he plots your end." No one doubts his skills as a political survivor, and not even his apologists deny his wish to be president of South Sudan, a job he coveted long before it existed.

The son of a minor Nuer chief, as a child (the 26th of 32) he attended an American missionary school. When he was suspended for leading his class in a song advocating southern independence, the story goes, his mother didn't punish him but bought him his first pair of trousers. A doctorate in England later followed, and he lets no one forget it: If asked to describe the Nuer, he recommends the books of ethnologist E.E. Evans-Pritchard. In wielding power among his tribesmen, though, he mingles the foreign credentials with local mysticism, reminding them that Nuer prophecy speaks of a gap-toothed, left-handed savior, physical attributes of his. When, as a SPLA commander in Upper Nile in the 1980s, he outlawed the gaar, the traditional Nuer face-scarring, priests objected. The gods wouldn't like it, they told him.

"I am part of the gods," he scolded them. "And that is my word!"

In early 2011, as independence approached, word spread that Machar was maneuvering to dislodge Kiir, the acting president. Nonetheless, to keep a lid on ethnic clashes, Kiir allowed him the vice presidency. Soon Machar was publicly castigating his boss. Their rivalry came to define South Sudanese politics. It was captured perfectly in the Othello vs. Iago dynamic of their official state portraits, which hung everywhere: Gen. Salva Kiir Mayardit, as his nameplate read, looking blunt and laconic; and Dr. Riek Machar Teny Durghon, wearing a wily, bumptious almost-grin.

By the time those portraits were printed, the elation of independence had evaporated, like a dream upon waking. As though overnight, the long-pined-after utopia of South Sudan had revealed itself to be a militarized one-party kleptocracy. The SPLM was accused of rigging elections; its security forces harassed, detained, and tortured political opponents, journalists, and human rights workers; its soldiers continued to kill civilians as a matter of routine. The army "dominated every critical aspect of life in South Sudan," according to a UN report, a fact that "seriously undermined governance and state institutions, making it difficult to establish the rule of law."

Corruption was already so bad by 2012 that Kiir admitted, in a letter published in newspapers, that billions that should have gone into state coffers had instead gone into pockets. He didn't need to add that those pockets belonged to people he knew. "We fought for freedom, justice and equality. Many of our friends died," he wrote. "Yet, once we got to power, we forgot what we fought for."

He was right, but that didn't win him much credit. (In a follow-up letter, he asked the malefactors to return the funds in exchange for impunity.) South Sudanese, so many of whom had lived in exile in functioning democracies abroad, knew they were not in one now. By last year it was widely assumed that, if there wasn't a coup, there would be a popular uprising.

In July 2013 Kiir fired Machar. At a press conference Machar accused him of "dictatorial tendencies." On the night of December 15, in a barracks in Juba, Dinka soldiers in the presidential guard apparently attempted to disarm their Nuer colleagues. A firefight ensued. Soon units of Dinka soldiers were moving door-to-door through Nuer enclaves, according to witnesses, executing people. According to some, the exteriors of Nuer homes had been marked beforehand, suggesting a premeditated plan. Nuer in turn retaliated against Dinka. The army split into Dinka and Nuer halves, and within days the fighting had spread across the country.

Nuer civilians, their neighborhoods strewn with corpses, fled to the UN compound in Juba. There, in June, I spoke with a group of village elders. One had watched his brother shot dead and his sister-in-law shot in the legs in front of their children. When he grabbed a soldier and pleaded with him not to kill him in front of the children, the soldier beat him to the ground with his rifle butt. He claims the soldier said, "Because you're Nuer, because you're the people of Riek Machar, we can kill you." For some reason, the soldier didn't kill him.

As we spoke, a young, shirtless man walked by the tent we were sitting in, mumbling to himself and gesticulating wildly. "Do you see that boy?" he asked. "He was forced to drink the blood of a man who was killed in front of him. It made him mad."

Close to 50,000 people were living in the compound, which, along with other camps around the country, was flooded by the seasonal rains. There were outbreaks of cholera, tuberculosis, and typhus. In the camps in Malakal and Bentiu, women waited their turn to bury their children. The war devastated the harvest of sorghum and other food staples. Several counties are now suffering famine. But even those refugees whose homes hadn't been destroyed refused to return to them. They believed they'd be killed by the government, or the White Army, as soon as they did. The UN estimates that a million people remain displaced.

Fighting for a Symbol

Back at Machar's camp, boredom prevailed. Having risen from their earthen beds at dawn, his troops put on their uniforms, listened attentively to the BBC, then sat around on ammunition canisters. I spoke with soldiers who'd escaped the violence in Juba in December. One, a Dinka, told me that he'd been loyal to Kiir, but when he saw that Dinka troops were killing their Nuer colleagues indiscriminately (on Kiir's orders, he believed), he felt compelled to join Machar.

After emerging from a camping tent next to the weapons cache, Machar was served tea. An attendant slowly rolled on his socks. That afternoon, as the brass played cards in their pajamas and gym shorts, Machar settled into his desk chair. "I did not think of fighting another war," he told me, as the sentries took up their positions. "I spent my best time, my productive years, prosecuting a war of liberation. I don't want to spend the rest of my life in another war." He sighed. "So they talk about peace. I tell them I want peace. But provided this republic is a democratic nation, there are freedoms in it, there's dignity of the people, there's justice.

"It's not only the Nuer," he went on. "It's the South Sudanese. The Dinka need to be protected also from [Kiir], you know. They're being coerced to go and fight a war which they really have nothing to benefit from." He added, "So maybe very soon we'll take them all and march to Juba."

This is not the first time Machar has made that threat. In 1991 he broke from the SPLA leadership, decrying its "dictatorial tendencies." The allegation was fair, and Machar was hardly the only southerner tired of the SPLA, but what he did next was inexplicable, or perfectly explicable, depending on your opinion of him: He got on the radio to say that he, Machar, was taking over the liberation movement. The claim wasn't vaguely true, and Machar fled to Nasir, where he fomented a rebellion, just as he would 22 years later. In the ensuing ethnic conflict, he and the SPLA were both responsible for mass killings of civilians. Machar managed to bill himself as the natural leader of the Nuer. Eventually he and the SPLA reconciled. But many southerners have never forgiven Machar.

I brought this up, noting that his critics said he was isolating himself now just as he had then. His eyes narrowed. "I didn't isolate myself in 1991. I did very well," he said. Before his break with the SPLA, "people were afraid to talk of right of self-determination for South Sudan, or of independence. Today we're independent. I'm proven right. Self-determination, independence of South Sudan, is us," he said. "And, in particular, it's me."

As he talked, he picked up Why Nations Fail again and brought it to his face, as though intending to channel some historical wisdom. He held the book upside down. "You know, people who fight for freedom, who defend their dignity, to bring about justice," he said, "they don't wait for the international community to accept them, to give them sanction to fight. Or else they would never fight."

I told him about a White Army insurgent I'd met in a hospital who'd been shot while fighting for Malakal. Thousands had been killed in the battles there. I pointed out that the city was not worth it: It was the heart of Nuerland, true, but held little strategic value. Why expend so many lives?

"Why fight over Atlanta?" he said, referring to the American Civil War. "It's a symbol."

Why Nations Fail

It is often said—it has been said countless times in South Sudan—that nothing brings a nation together like grievance. That may be true. But if it is, it is no less true that nothing strangles a nation like grievance.

South Sudan's failure to live up to its noblest aspirations for itself, however, cannot be blamed entirely on Machar, or Kiir, or on any one person or group. The problems go far deeper. The extent to which a half century of near-continuous conflict have brutalized and hollowed out southern Sudanese society cannot be overstated. War, all-encompassing, all-infecting, has robbed the southern Sudanese of their traditions, their livelihoods, their very identities. Two generations of people who might have been farmers, teachers, doctors, lawyers, priests, mothers, fathers have instead become soldiers in a war that never ends. And the violence has left life cheap, unbearable, contemptible even. Independence only brought the violence to an official end, it turns out, not a psychological one. Though independent, many southerners had, by 2011, come to believe, unconsciously or otherwise, the north's scornful conception of them—that they were too combative and selfish to handle liberation.

"The war left behind gaping wounds in the hearts and minds of people about the value of liberation. They asked, liberation to what end?" historian Jok Madut Jok said. The idea that South Sudan could "march home from a war in the bush, and [take] the helms of power, thinking that things can just go on without anybody working to heal these wounds—that was where it all began to fall apart."

On the way back into Ethiopia, one of Machar's generals traveled with Sarah Kier. As they sat in a teahouse awaiting a ride, she told him she wanted to become a field commander. He asked why. Because, she said, he and the other men around Machar were running the rebellion into the ground. They had no plan aside from killing. "If I was in charge of this war, I'd do things differently than you men are, I can tell you that," she told him. "You know, the strategy should not be on the number of lives [taken]."

As though to bear her out, the next week Machar's troops and the White Army retook the city of Bentiu. They drove out government soldiers and, in the process, slaughtered hundreds of civilians. It was the worst atrocity of the war. Images of piled, burnt bodies were broadcast around the world. The U.S. put sanctions on Machar and his allies. Not long after that, government forces overran Nasir. Machar fled. He is now in and out of Addis Ababa, awaiting peace talks that keep getting postponed.