Gettysburg was no ordinary battle. These maps reveal how Lee lost the fight.

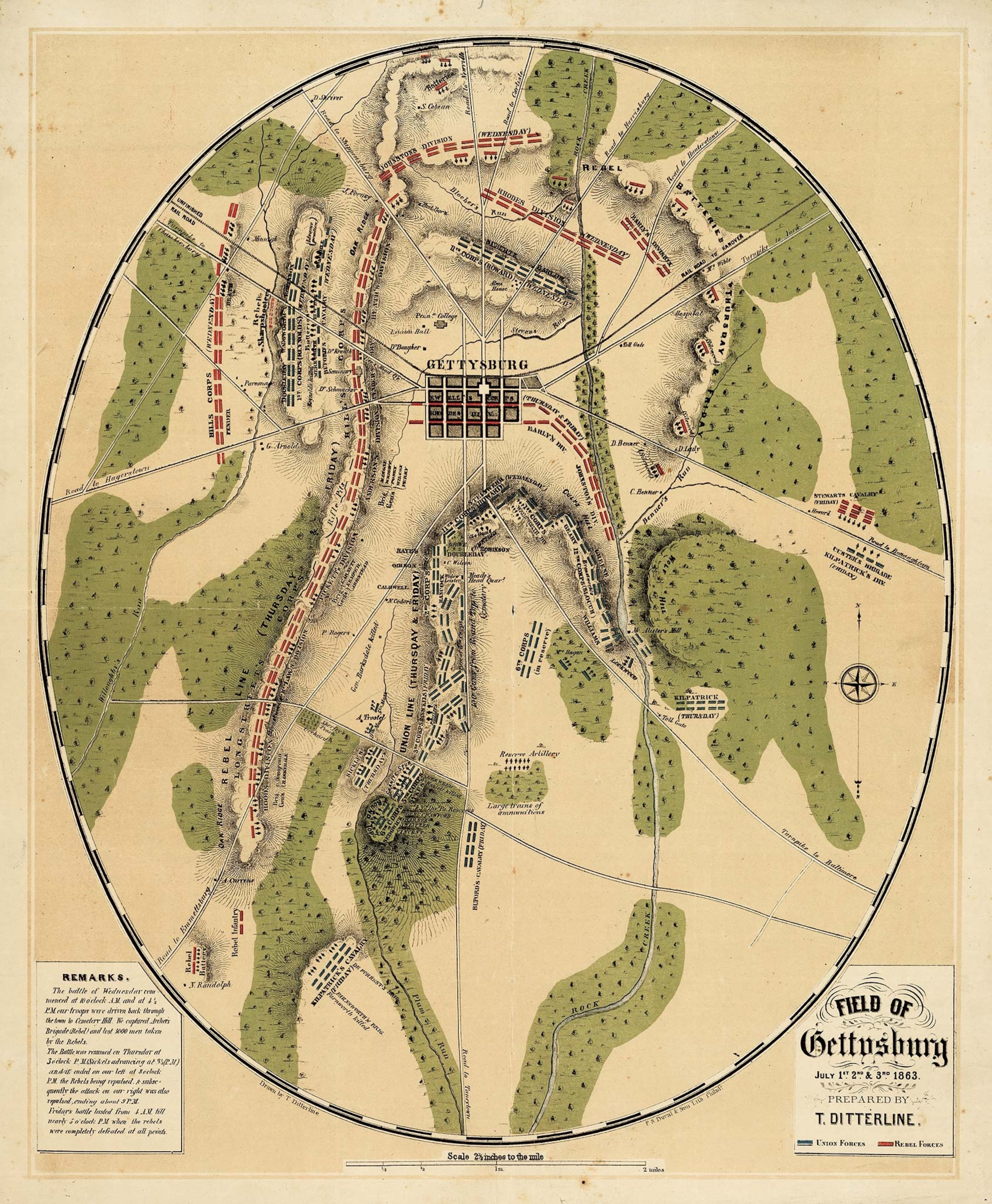

The distinctive terrain—from its hills and ridges to its rocks and fields—played a pivotal role in the July 1863 battle whose victory revitalized the Union.

Before the Civil War, the biggest thing to happen in Gettysburg was a new railroad. Finished in 1858, it connected the Pennsylvania farm town to Hanover Junction some 20 miles away. From there, travelers could continue by rail to Baltimore or Philadelphia. Gettysburg might have stayed inconspicuous had it not been for the events of July 1863.

Sitting near the Pennsylvania-Maryland border, Gettysburg became the site of the Civil War’s most famous battle. Perhaps more than any other battlefield, Gettysburg is known for its geography: the hills and ridges, the rocks and fields—each location the site of pivotal moments in the bloody battle fought over the first three days of July 1863.

(How mail-in voting began on Civil War battlefields.)

Summer of ’63

The Civil War was well into its second year by June 1863. Fighting had reached a fever pitch the previous winter. Traditionally, winters were times for armies to rest and recoup, but the commanders on both sides defied the elements and kept campaigning.

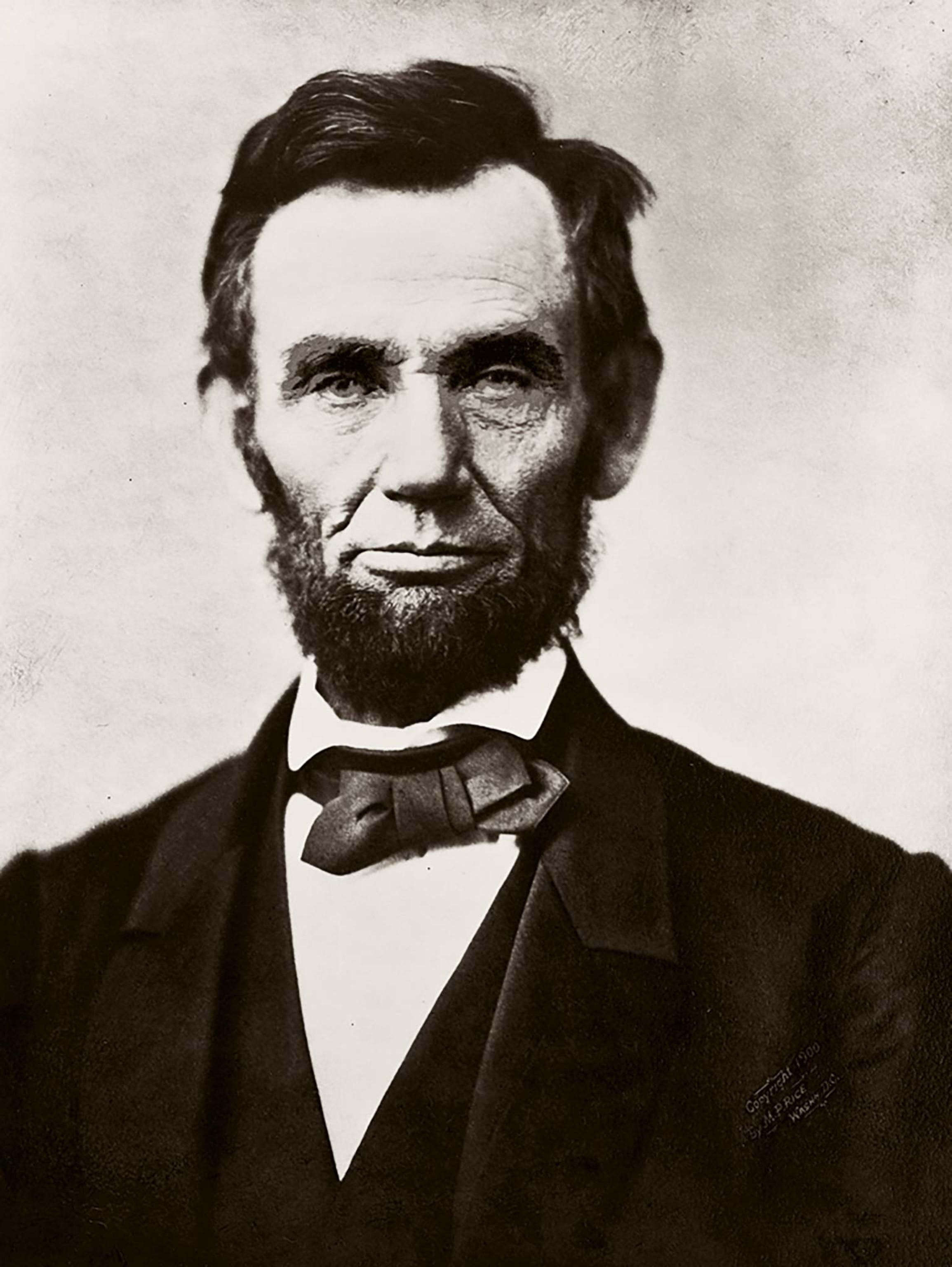

Union forces in the West were holding strong and steadily gaining ground throughout the spring, but the eastern theater proved more challenging. President Abraham Lincoln grew frustrated with the Army of the Potomac’s leadership, especially after the Confederacy scored major victories at Fredericksburg in December 1862 and Chancellorsville in May 1863.

On the rolling fields of Gettysburg, the newly appointed Union commander, George Meade, led some 90,000 Union soldiers against 75,000 Confederates. At battle’s end, more than 50,000 men had been killed, wounded, or missing. Hailed by many as a turning point in the war, the Union victory repelled a surging Confederacy. Though it ushered a shift in momentum, Gettysburg was not a killing blow for the Confederacy.

Two more years of war would follow, but the win revitalized the North after news of it spread. Philadelphia headlines trumpeted “Victory! Waterloo Eclipsed!” After news broke of another Union triumph in the West at Vicksburg, an impromptu group of singers at the White House serenaded Lincoln, who told them:

"This last Fourth of July just passed, when we have a gigantic Rebellion ... we have the surrender of a most powerful position and army on that very day, ... and in a succession of battles in Pennsylvania, near to us, the cohorts of those who opposed the declaration that all men are created equal, 'turned tail' and ran. Gentlemen, this is a glorious theme, and the occasion for a speech, but I am not prepared to make one worthy of the occasion."

Months after Gettysburg, Lincoln had a chance to present remarks worthy of the occasion that echoed his extemporaneous expressions from that July night. In November he took the Gettysburg Railway to the Pennsylvania battlefield to honor the fallen and gave a speech that completed the small town’s transformation into an American mecca.

June 1863: Buildup to battle

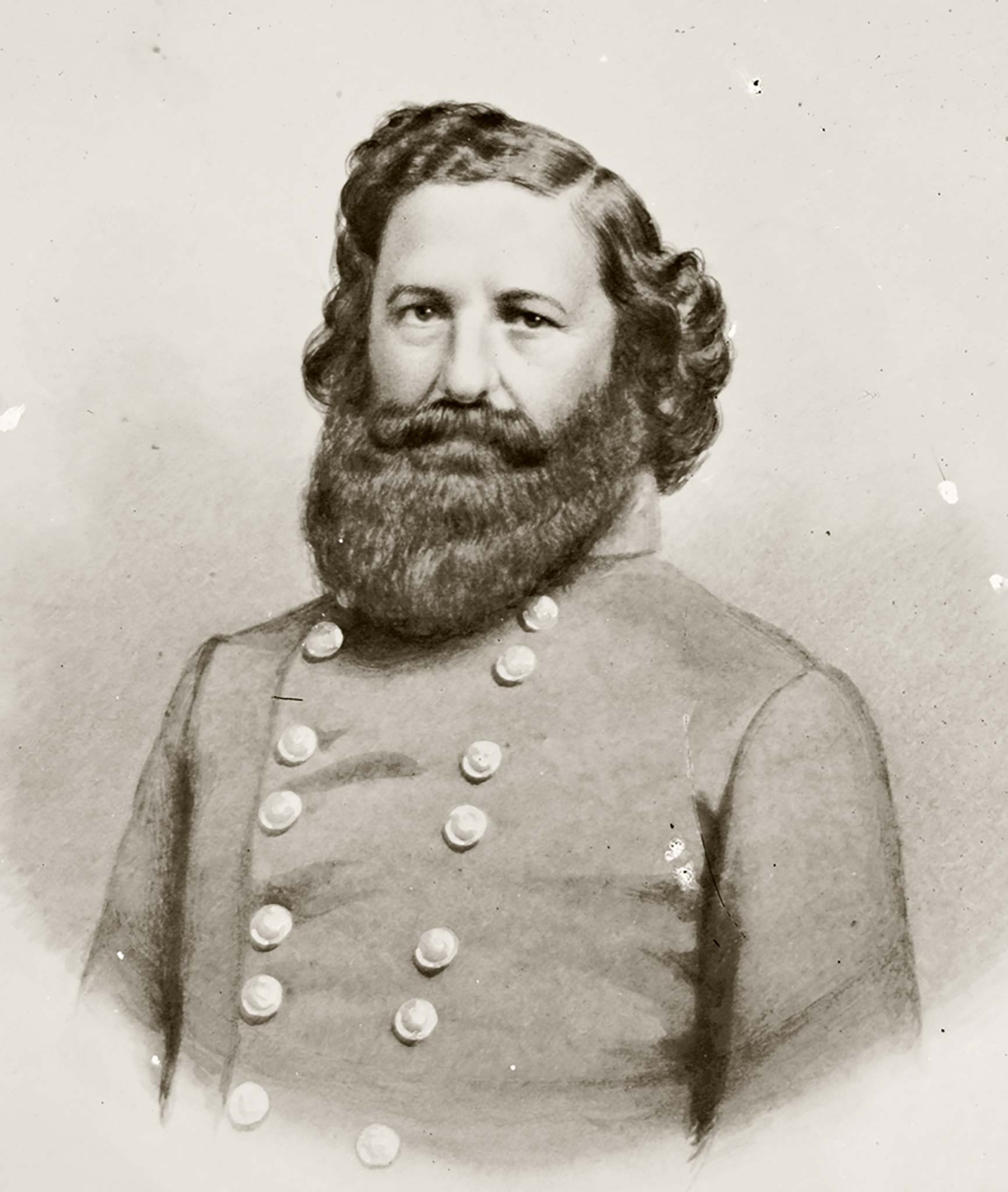

Gen. Robert E. Lee’s victory at Chancellorsville came at a steep price and left him determined to abandon his defenses at Fredericksburg and carry the fight north.“Our loss was severe,” he concluded,“ and again we had gained not an inch of ground.” Following the death of Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson on May 10, Lee welcomed the return of his “old warhorse,” Lt. Gen. James Longstreet, who had been sent to southeastern Virginia with 20,000 men to shield Richmond and ease the burden of feeding Lee’s army. Conferring with Lee, Longstreet agreed that “fruitless victories” like Chancellorsville “were consuming us, and would eventually destroy us.” Lee decided to launch another invasion of the North—an advance into Pennsylvania that would allow his hungry, ragged troops to forage at the Union’s expense and might result in a victory that would advance his cause.

Lee launched his campaign on June 3 after reorganizing his army into three corps under Longstreet, Lt. Gen. A. P. Hill, and Lt. Gen. Richard Ewell. Ewell would take charge of Jackson’s old corps, while Maj. Gen. Jeb Stuart resumed his duties as Lee’s cavalry commander. Union general Joseph Hooker ordered his cavalry commander, Maj. Gen. Alfred Pleasonton, to “disperse and destroy” Stuart’s force, leading to the war’s largest cavalry battle, waged at Brandy Station on June 9.

Stuart prevailed there and went on to shield Lee’s forces as they filed through gaps in the Blue Ridge Mountains and the Shenandoah Valley. Ewell led the way north, seizing Winchester from Federals in mid-June before passing through Maryland into Pennsylvania, where his corps divided, raiding Carlisle and threatening York. Hill’s corps followed Ewell into Pennsylvania, with Longstreet and Lee bringing up the rear.

On June 25, Stuart embarked on an expedition around the Union army, leaving Lee ill-informed on enemy movements as Hooker plodded northward into Maryland, east of the mountains. Exasperated at Hooker’s slow pace, Lincoln sacked him on June 28 in favor of Maj. Gen. George Meade, who promptly sent Brig. Gen. John Buford’s cavalry division into Pennsylvania, followed by the First and 11th Corps. On June 30, Buford entered the quiet town of Gettysburg, where a dozen roads converged and two great armies would soon collide. That evening, Lee received a message at Chambersburg from Hill at Cashtown stating that hostile forces were reported in Gettysburg and he would “advance the next morning and discover what was in my front.”

(Photos of Robert E. Lee statue, taken down after a court ruling, throughout time.)

July 1, 1863: The battle erupts

At dawn on July 1, Confederates of Maj. Gen. Henry Heth’s division, leading the way for Hill’s corps, approached Gettysburg along the Chambersburg Pike. They expected to find the town lightly defended by militia. Instead, they confronted 3,000 dismounted Federal troopers, led by Buford, that would be bolstered at midmorning by the arrival of the First Corps under Maj. Gen. John Reynolds, who would later be shot dead as he hurried men into line along McPherson’s Ridge. Heth’s troops fell back toward Herr Ridge, where they were reinforced by another of Hill’s divisions, led by Maj. Gen. William Pender.

Lee arrived from Chambersburg at midday, ahead of Longstreet’s corps, to find Ewell’s divisions approaching from the north and east. “I do not wish to bring on a general engagement today,” he told Heth. “Longstreet is not up.” But it was too late, and Lee saw an opportunity to annihilate the Federal vanguard at Gettysburg before Meade’s army got there. Told by Lee to attack as he saw fit, Ewell came in from the north with the division of Robert Rodes, who launched an assault along OakRidge, which was teeming with Yankees. Despite that debacle, Lee gained the upper hand by sending Hill’s forces against the battle-weary First Corps while another of Ewell’s divisions, under Jubal Early, swept in from the northeast along Harrisburg Road and surprised Oliver Howard’s 11th Corps.

Caught in a vise, the Federals cracked and retreated south to high ground, where Winfield Scott Hancock rode ahead of his Second Corps. He recognized that the Federals held a stronger position. “We can fight here,” he wrote Meade, who arrived overnight on the road from Taneytown, Maryland, with the bulk of his army to fill out a line around Culp’s Hill and nearby Cemetery Hill and extend southward along Cemetery Ridge to Little Round Top. This interior line was two miles shorter than Lee’s exterior line, givingMeade a greater density of troops that he couldshift readily from one position to another. The battle that would determine “the fate of our country and our cause,” in Meade’s words, would be decided here at terrible cost over the next two days.

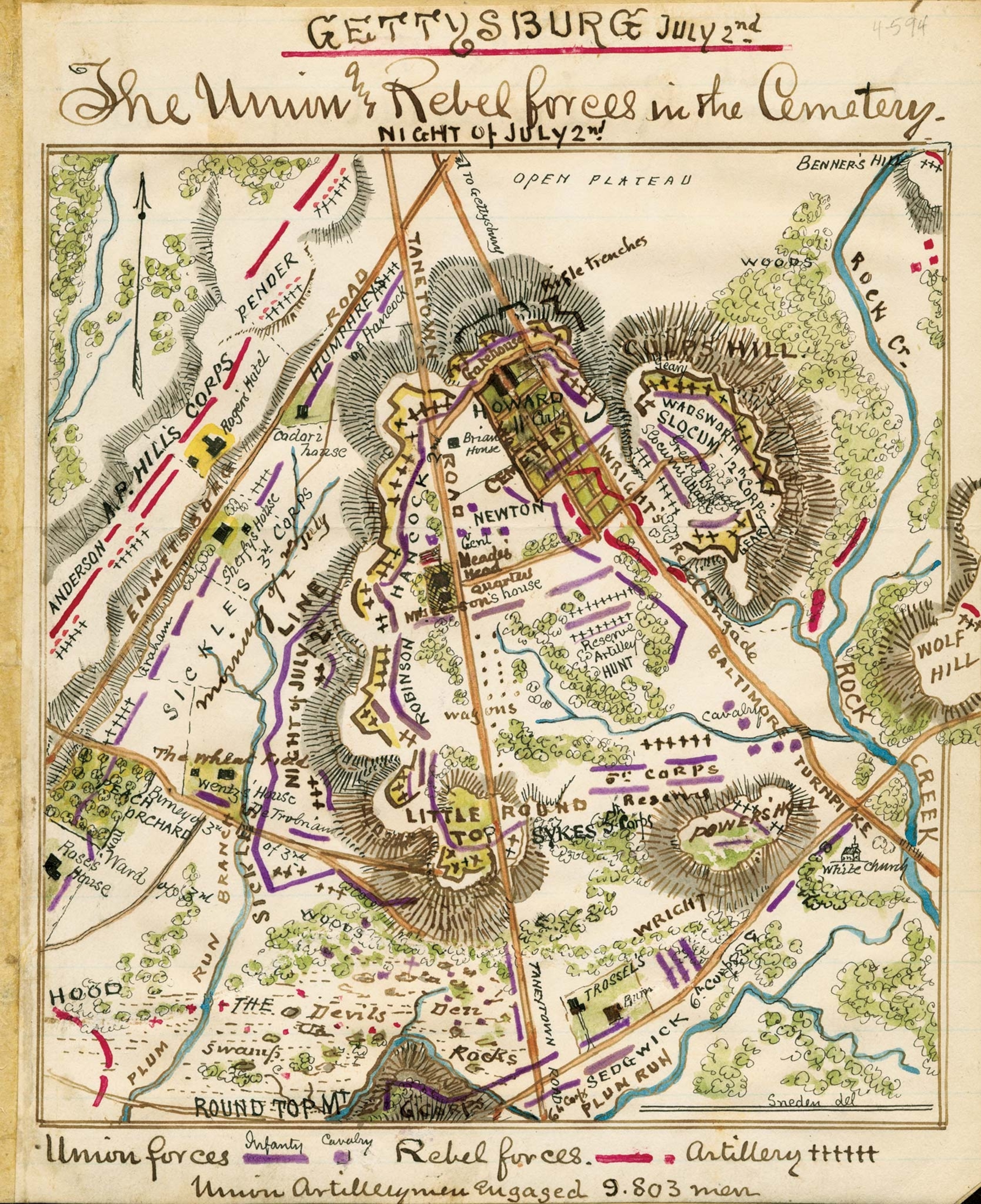

July 2, 1863: Little Round Top

Early on July 2, Meade bolstered his right flank at Culp’s Hill, where he expected an attack, by shifting Brig.Gen. John Geary’s 12th Corps division there from Little Round Top, which anchored the Federal left flank and offered a commanding perch for artillery. Meade expected Daniel Sickles to extend his Third Corps line southward from Cemetery Ridge to cover Little Round Top. But Sickles, a headstrong political general from New York, decided instead to advance his line westward from Cemetery Ridge—so low in places that it was barely perceptible—to slightly higher ground around the Peach Orchard. Little Round Top remained undefended as Lee prepared to hit Meade’s left hard.

(Here’s what might replace America’s disappearing Confederate monuments.)

Lee’s plan called for two newly arrived divisions of Longstreet’s corps, led by Maj. Gens. John Bell Hood and Lafayette McLaws, to mount that attack, with support from Maj. Gen. Richard Anderson’s division of Hill’s corps. Longstreet urged Lee to forgo that risky assault, or at least postpone it until his trailing division, under Maj. Gen. George Pickett, arrived from Chambersburg. “I never like to go into battle with one boot off,” Longstreet said. Ordered by Lee to proceed, Longstreet moved slowly, countermarching his troops at one point to avoid detection, and did not unleash Hood’s division—slated to launch the attack—until 4 p.m. By then, Meade had learned of Sickles’s blunder and sent his chief engineer, Brig. Gen. Gouverneur Kemble Warren, to Little Round Top. Finding it exposed, Warren sought help, furnished promptly by Col. Strong Vincent of the Fifth Corps, who rushed his brigade up the hill before the Rebels got there.

Part of Hood’s division advanced through Devil’s Den, below Little Round Top, ousting Sickles’s men in what a Texan fighting there called “one of the wildest, fiercest struggles of the war.” Hood was seriously wounded early on, and Brig. Gen. Evander Law took charge, leaving no brigade commander to direct the crucial attack on Vincent’s men guarding Little Round Top. “Hold this ground at all costs!” Vincent told Col. Joshua Chamberlain, whose 20th Maine Infantry occupied the very end of the Union line. After withstanding repeated assaults by the 15th Alabama Infantry, Chamberlain’s men scattered their foes with a bayonet charge. Heavy fighting continued elsewhere until Brig. Gen. Stephen Weed came to the aid of the mortally wounded Vincent and secured Little Round Top for the Union at the cost of his own life.

July 2, 1863: War in the Wheat Field

The battle raged in the Wheat Field, where Sickles’s beleaguered Third Corps buckled under pressure from brigades led by Col. George “Tige” Anderson of Hood’s division and Brig. Gens. Paul Semmes and Joseph Kershaw of McLaws’s division. To hold the line, Meade reinforced the Third Corps with men led by Brig. Gens. James Barnes and John Caldwell. Barnes went in first but found Kershaw on his flank and pulled his forces back, obstructing Brig. Gen. Samuel Zook of Caldwell’s advancing division. “If you can’t get out of the way,” Zook shouted, “lie down, and we will march over you!” Passing through, Zook’s troops entered the Wheat Field alongside the Irish Brigade of Col. Patrick Kelly.

A third brigade under Col. Edward Cross joined in a bloody assault that left Cross and Zook mortally wounded but drove the Rebels into Rose’s Woods. Around 6:30 p.m., Brig. Gens. William Barksdale and William Wofford of McLaws’s division delivered a staggering blow at the Peach Orchard. Pouring through the gap left by the collapse of Brig. Gen. Charles Graham’s brigade, Wofford’s troop of Georgians drove Federals back while Barksdale’s Mississippians routed the remainder of Brig. Gen. Andrew Humphrey’s division along Emmitsburg Road. The tide turned when Sickles fell wounded near the Trostle House, and Hancock of the Second Corps took command. He restored order by rallying retreating units on Cemetery Ridge and bolstering them with reinforcements. After sending a brigade led by Col. George Willard to repulse Barksdale, Hancock beat back a charge led by Brig. Gen. Cadmus Wilcox, and Lee’s furious attack ended in a stalemate.

(Reconstruction offered a glimpse of equality for Black Americans. Why did it fail?)

July 3, 1863: Pickett's Charge

After two days of fighting, Lee did not give up. He ruled out another attack on Meade’s left, which had been heavily reinforced. Prospects for success looked little better on Meade’s right, where Confederates in Ewell’s division had advanced late on July 2, breaking through at Cemetery Hill before being repulsed there, as they were at Culp’s Hill. Further attacks by Ewell stood to prevent Meade from shifting forces from his right to bolster his center, along Cemetery Ridge, where Lee hoped for a decisive breakthrough. That meant advancing across open ground into the teeth of Union defenses—a perilous charge entrusted to George Pickett’s fresh division of 6,000 Virginians, with Brig. Gen. J. Johnston Pettigrew’s division advancing to their north and others following.

Lee’s plan went awry early on July 3, when Federals attacked Culp’s Hill, triggering a battle that ended inconclusively before Pickett was ready to advance. Lee still had hope that a massive artillery bombardment would impair Meade’s defenses on Cemetery Ridge. At 1 p.m., Rebel gunners opened fire. For all the sound and fury, little damage was done. Many Confederate gunners overshot their targets, while Federal artillerymen limited their counterfire to conserve ammunition. When the guns fell silent, Longstreet, who had argued against the attack, signaled reluctantly for the infantry to advance. “This is a desperate thing to attempt,” said Brig. Gen. Richard Garnett of Pickett’s division. “It is,” replied Brig. Gen. Lewis Armistead, whose brigade followed Garnett’s. “But the issue is with the Almighty, and we must leave it in his hands.”

To close up with Pettigrew’s division to the north, Pickett’s men had to march obliquely to their left, which exposed them to deadly flanking fire. Hardest hit were Brig. Gen. James Kemper’s men, who went down in droves when Vermonters led by 8 Brig. Gen. George Stannard enveloped their right flank. “Great masses of men seemed to disappear in a moment,” wrote Col. Wheelock Veazey of the 16th Vermont Infantry.

All along the line, Confederate ranks crumbled under the searing impact of artillery and infantry fire. Against all odds, Armistead led a few hundred followers over the stone wall at the Angle, where the Federal line jutted forward slightly, but they were soon overpowered in hand-to-hand fighting. As Lee’s battered forces withdrew, hopes for the Confederate cause receded with them.

(It took more than 200 years to end slavery. Juneteenth honors that fight.)

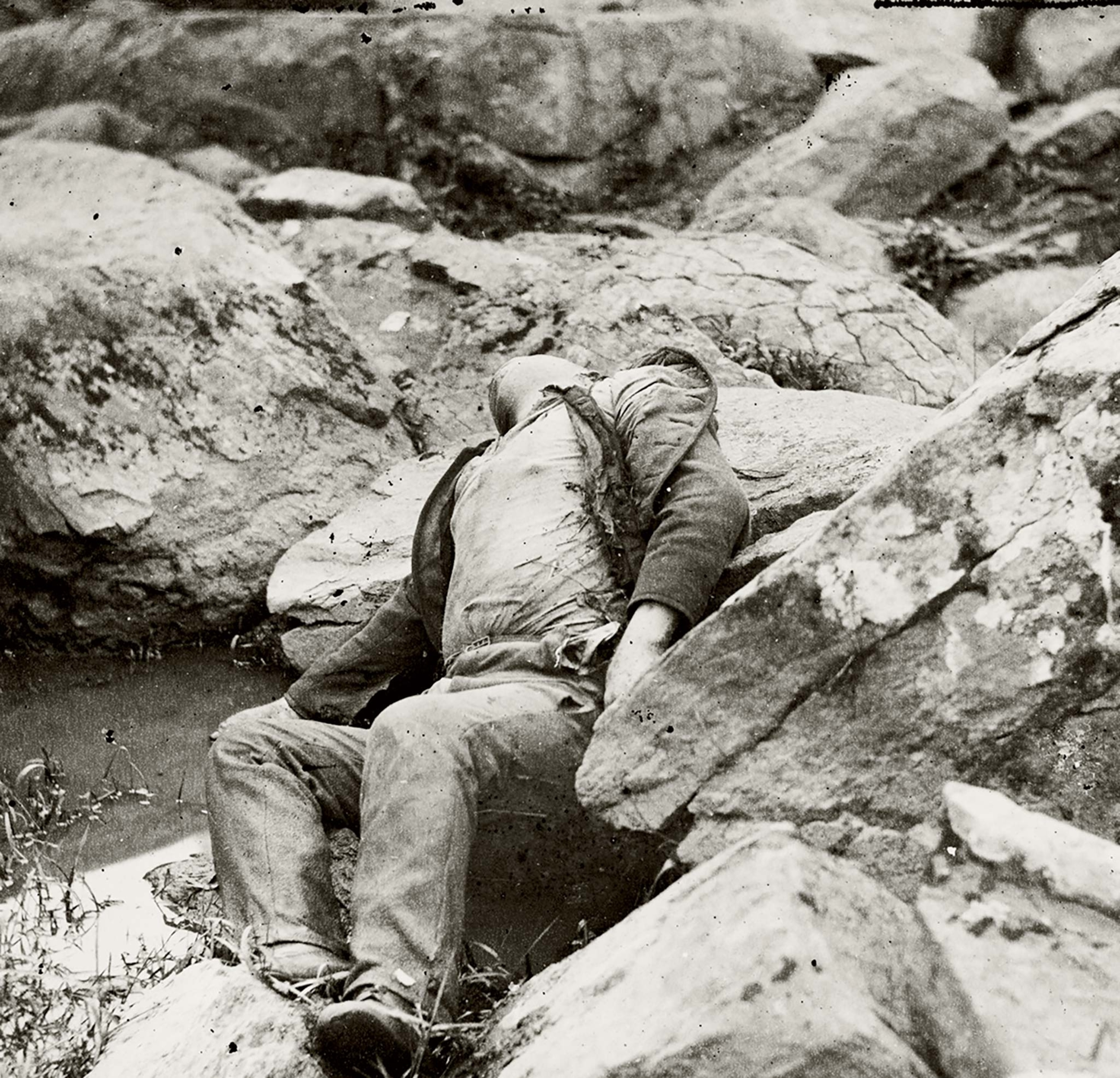

Aftermath: the final measure

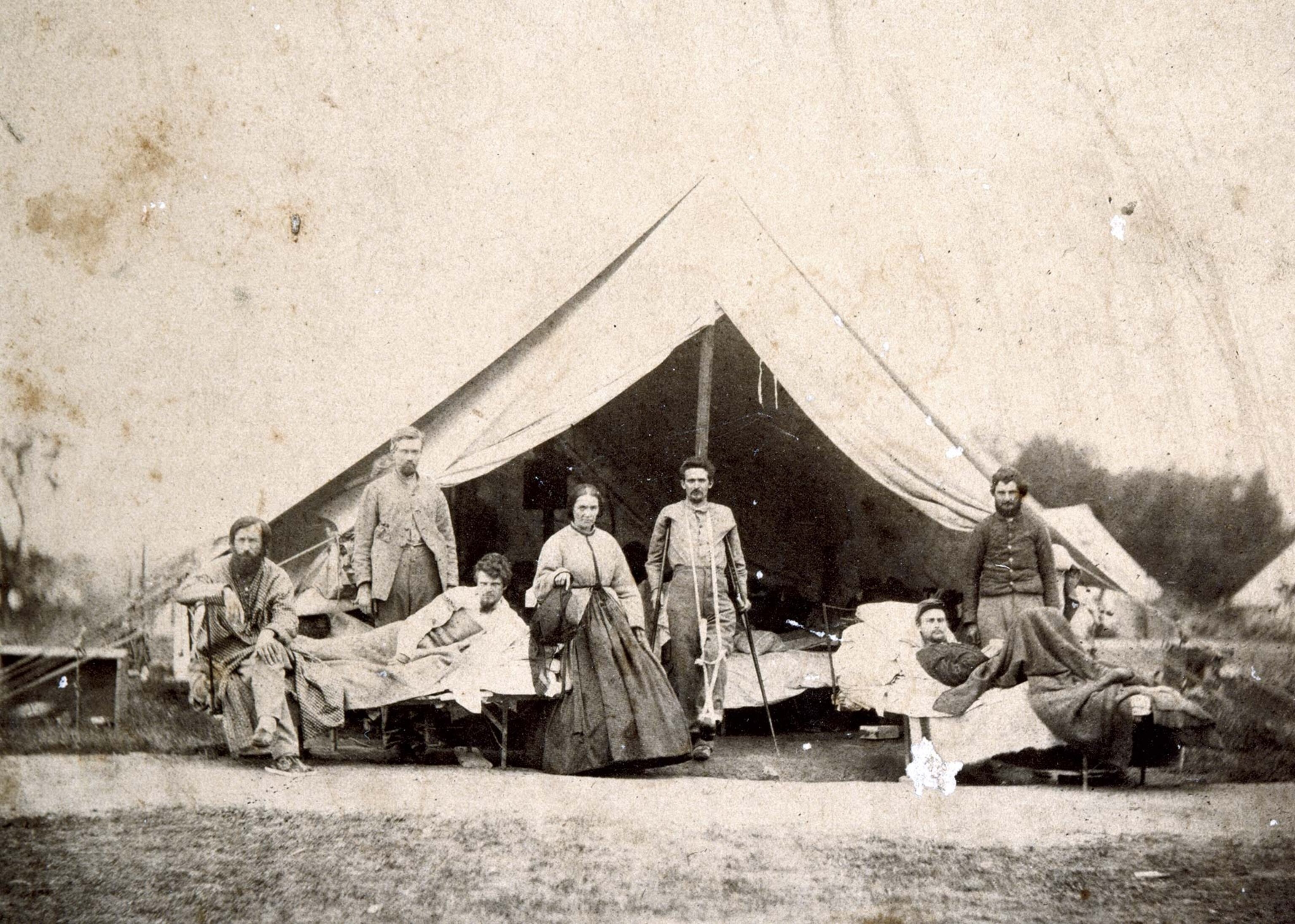

Like a monstrous storm, the Battle of Gettysburg left carnage in its wake. More than 50,000 men were killed, wounded, or missing in this tempest—a toll that bore harder on Lee’s smaller army and forced him to retreat into Virginia, leaving the dead behind. “Some with faces bloated and blackened beyond recognition, lay with glassy eyes staring up at the summer sun,” recalled Cpl. Thomas Marbaker of the 11th New Jersey Infantry. “Hugging the earth like a fog, poisoning every breath,” he added, was “the pestilential stench of decaying humanity.”

Burial parties digging in the hard, rocky soil did not linger over their grim task. “The dead are many, the time is short, so they got but very shallow graves,” wrote one soldier, “in fact most of them were buried in trenches, dug not over 18 inches deep, and as near where they fell as was possible.”

A few months afterward, remains of the Union’s dead were moved to the Soldiers’ National Cemetery, situated on Cemetery Hill, a local burial ground where Federals of Howard’s 11th Corps withstood Confederate attacks on July 2. This new cemetery held more than 3,500 bodies. Those whose identities were known were grouped by state, but nearly 1,600 graves were marked unknown. On November 19 President Lincoln dedicated the cemetery by delivering his Gettysburg Address, urging that “from these honored dead we take increased devotion to the cause for which they gave the last full measure of devotion.”