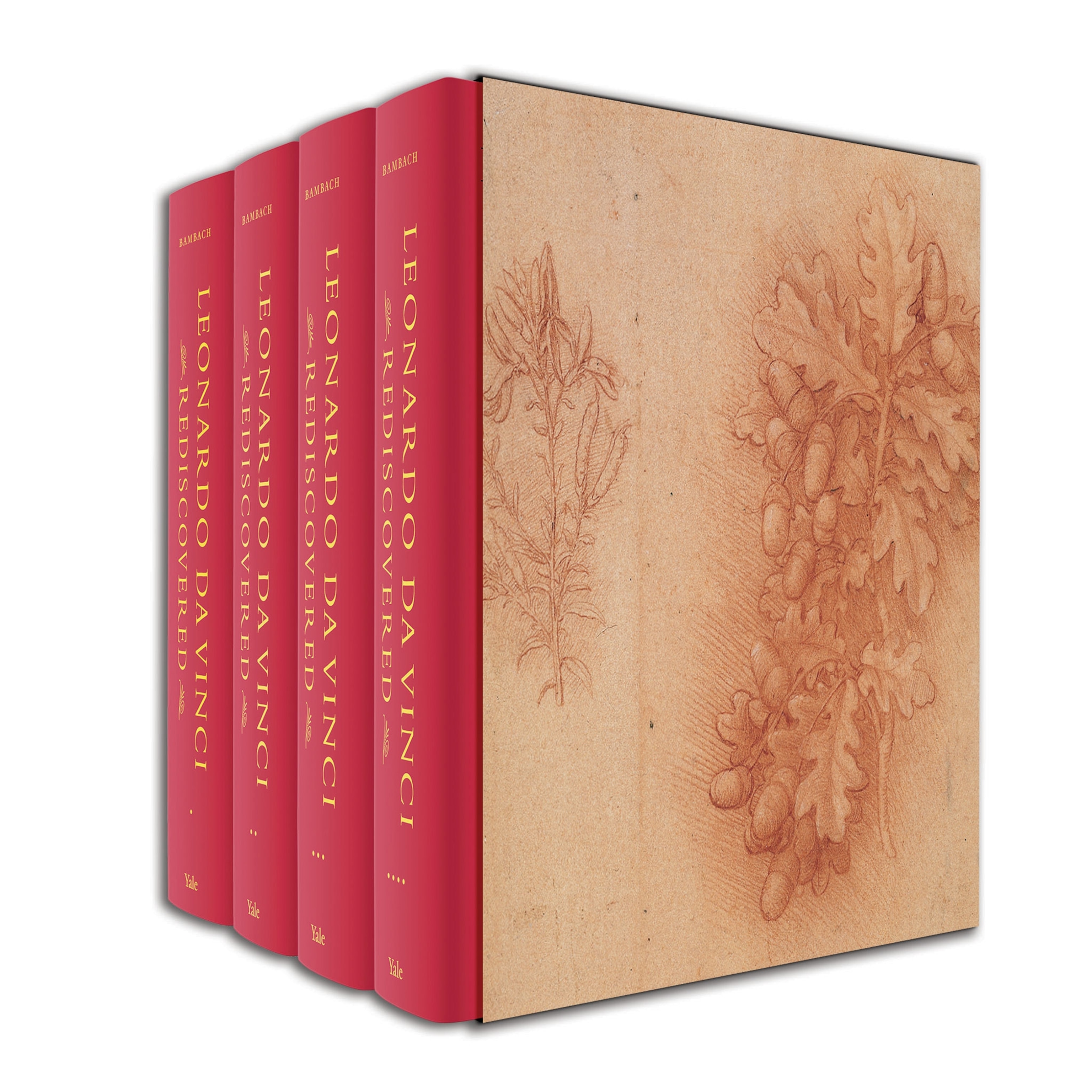

Carmen Bambach, curator in the Department of Drawings and Prints at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, spent 23 years studying the life and work of Leonardo da Vinci. The culmination of her research, a 2,200-page, four-volume book, Leonardo da Vinci Rediscovered, will be published by Yale University Press this summer.

In an interview at the Met, Bambach described what she calls the “archaeological method” she used to excavate details about Leonardo: she studied the intricacies of his handwriting; transcribed and translated the artist’s words herself instead of relying on previously published translations; and read the same books Leonardo read in their original form. Rather than focus on a single theme (anatomy or engineering) or on a single aspect of Leonardo’s artistic legacy (drawing or painting), Bambach resolved to present the artist in his entirety through the lens of both art historian and biographer.

In addition to launching her book, Bambach is curating a display of Leonardo’s unfinished painting, St. Jerome in the Wilderness. The painting, on loan from the Vatican Museums, will be on view at the Met from July 15 to October 6, 2019. (Read why Leonardo's brilliance endures 500 years after his death.)

Excerpts:

How does your approach to studying Leonardo differ from other scholars?

There are art historians who are fixated on the manuscripts, on themes, or on the chronology of his work. There are those who are more fixated on him as a painter or on his drawings. I took on a kind of challenge and it’s pretty risk-taking: Who is this man and what happens when we incorporate this into a biographical framework? How can we integrate Leonardo the artist, Leonardo the thinker, Leonardo the author? This book is really meant to show why biography matters.

Who is the Leonardo that emerges for you?

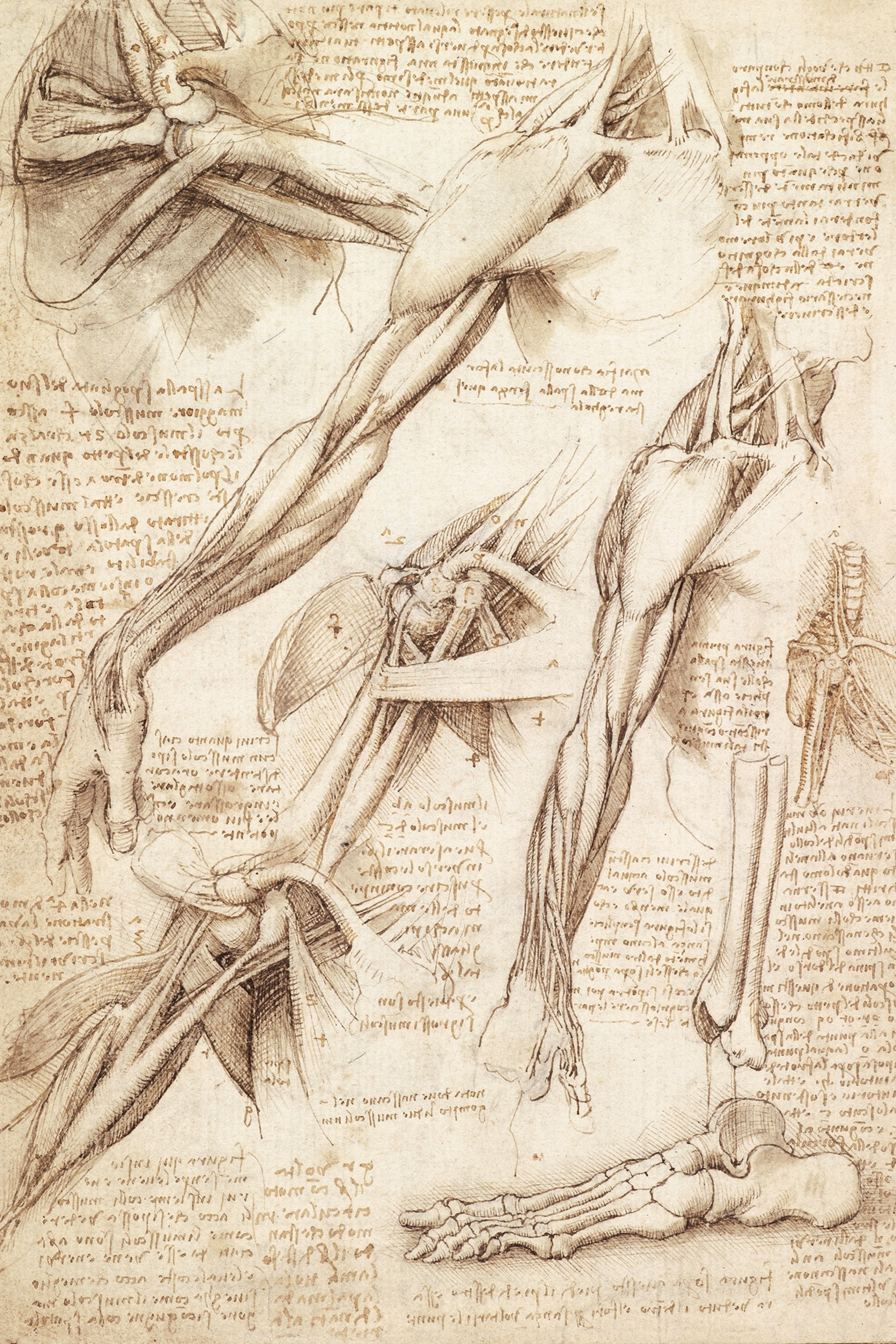

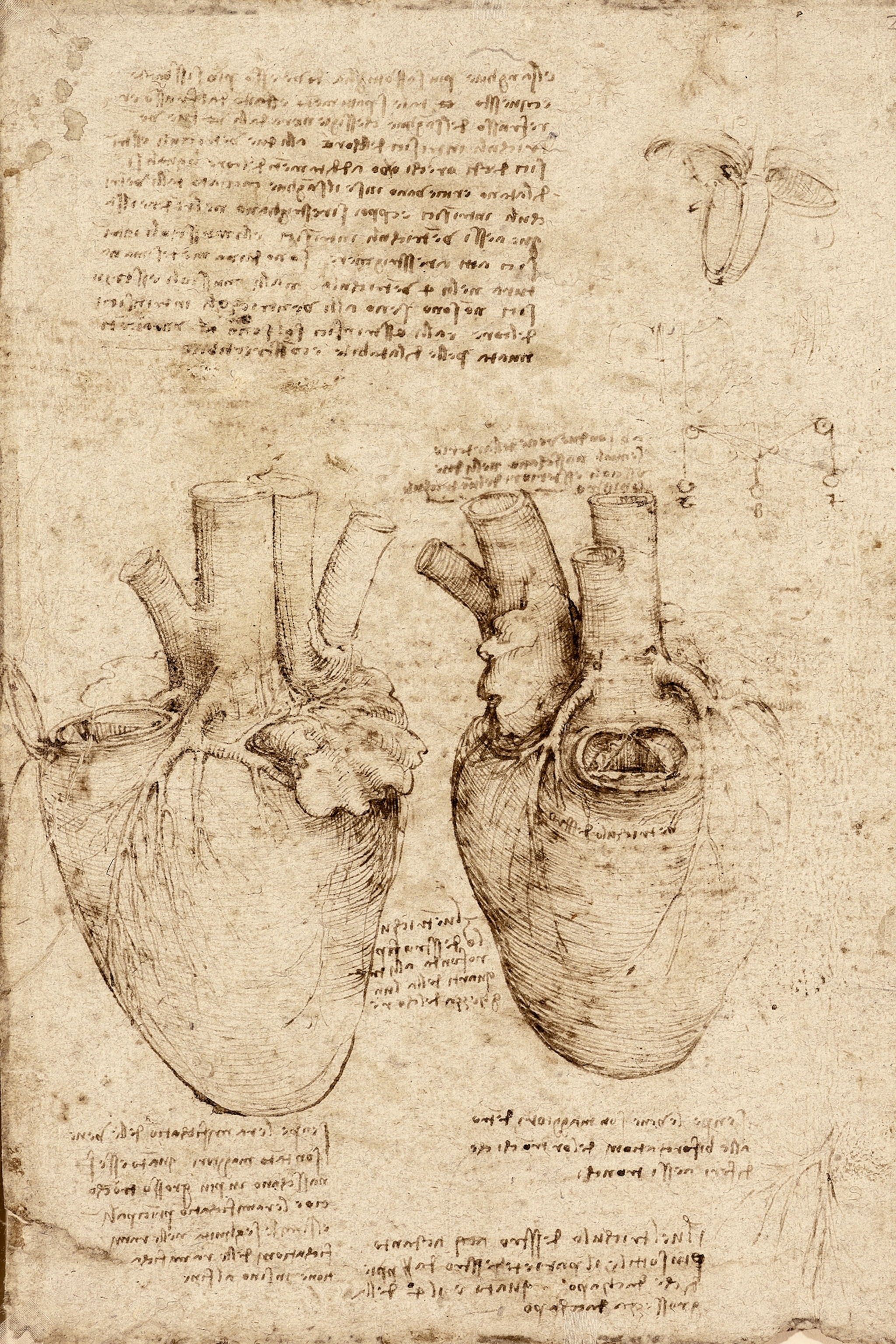

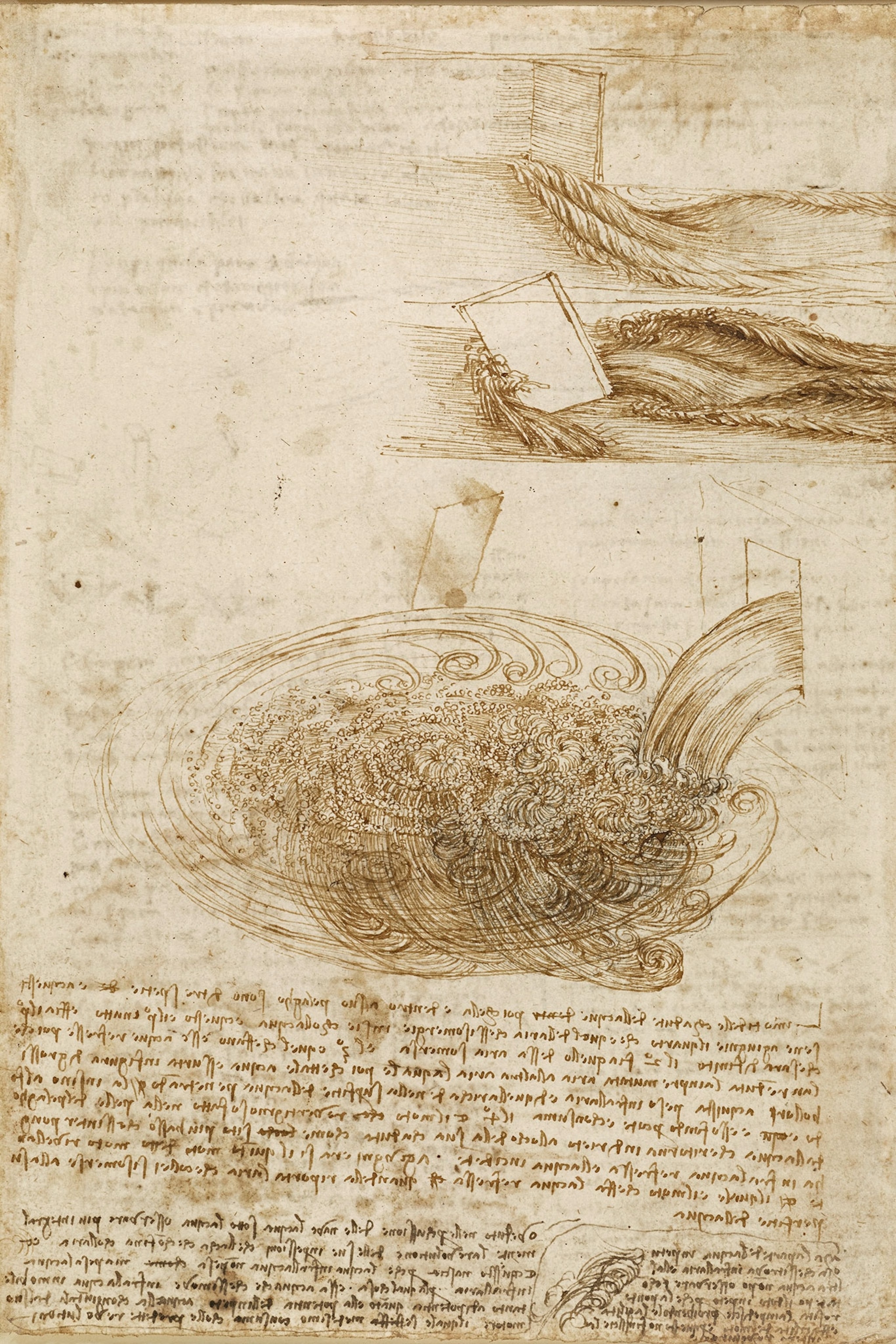

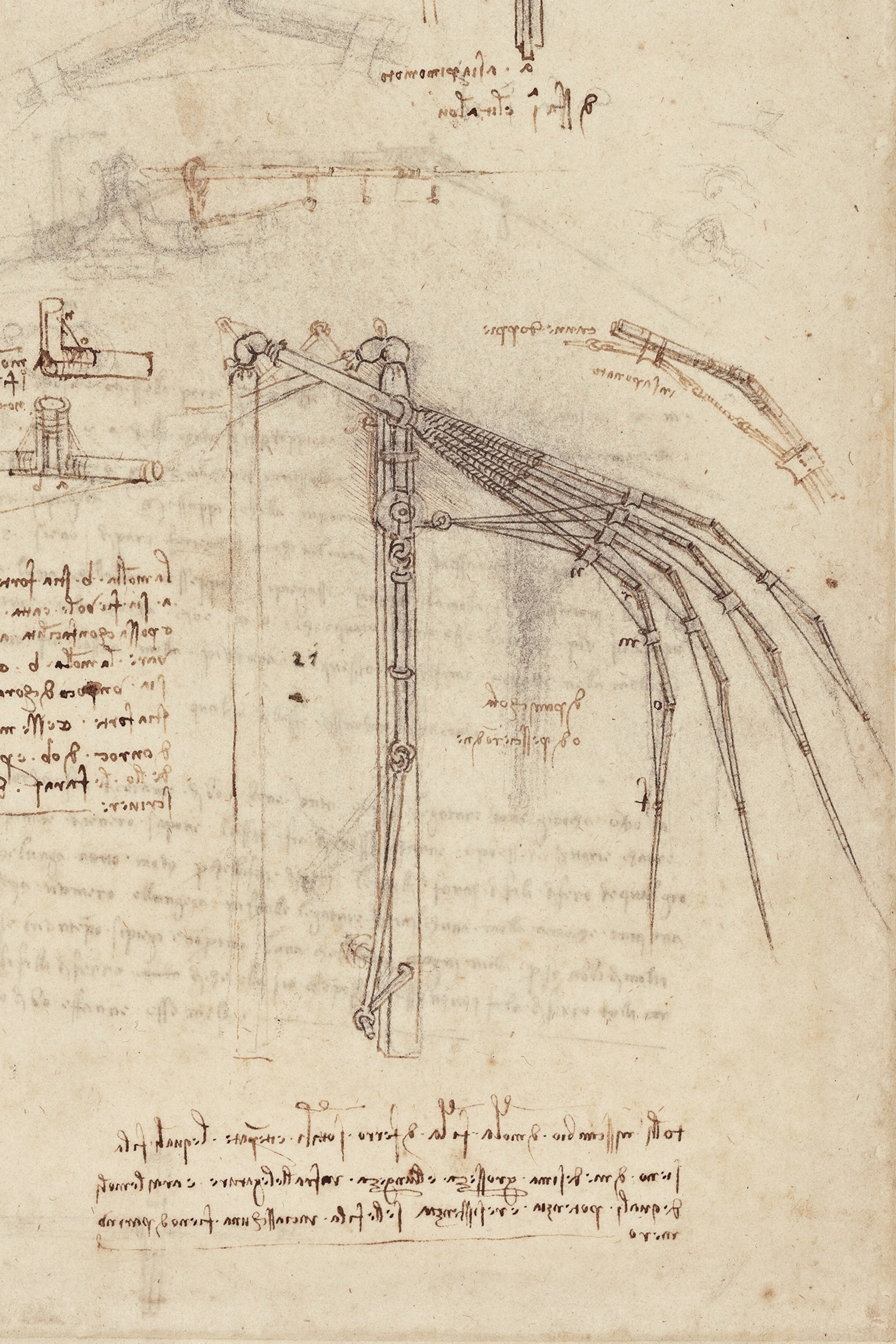

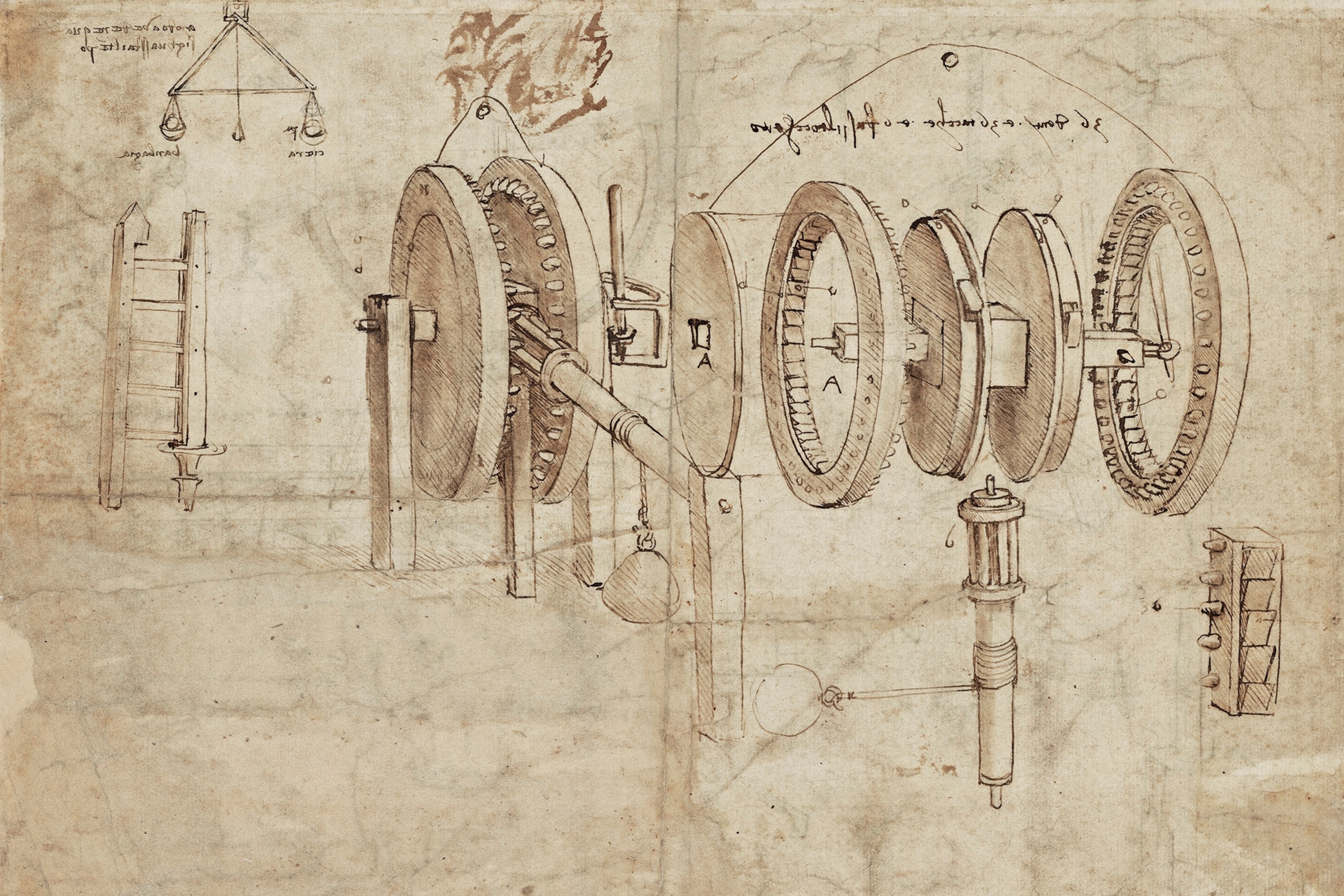

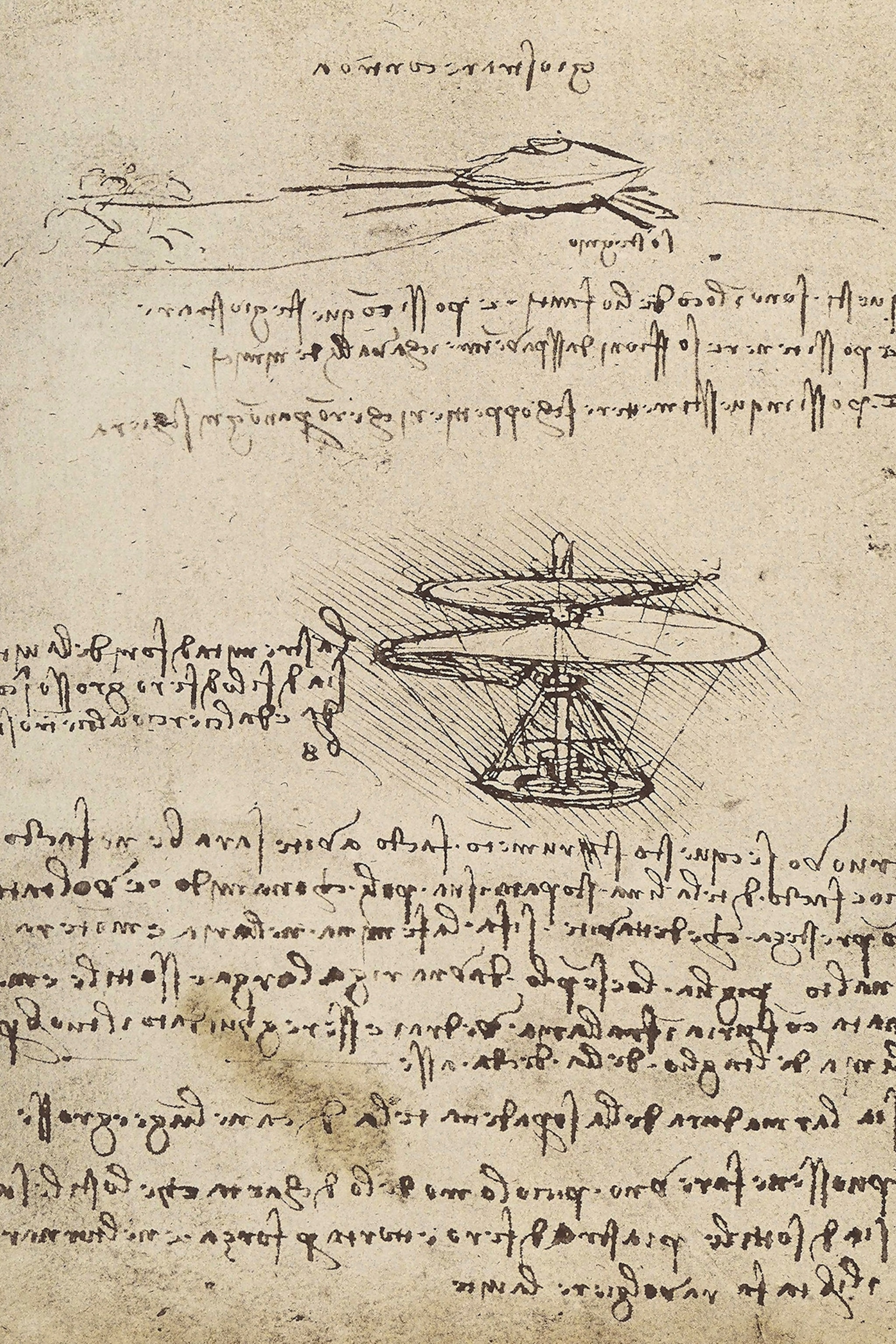

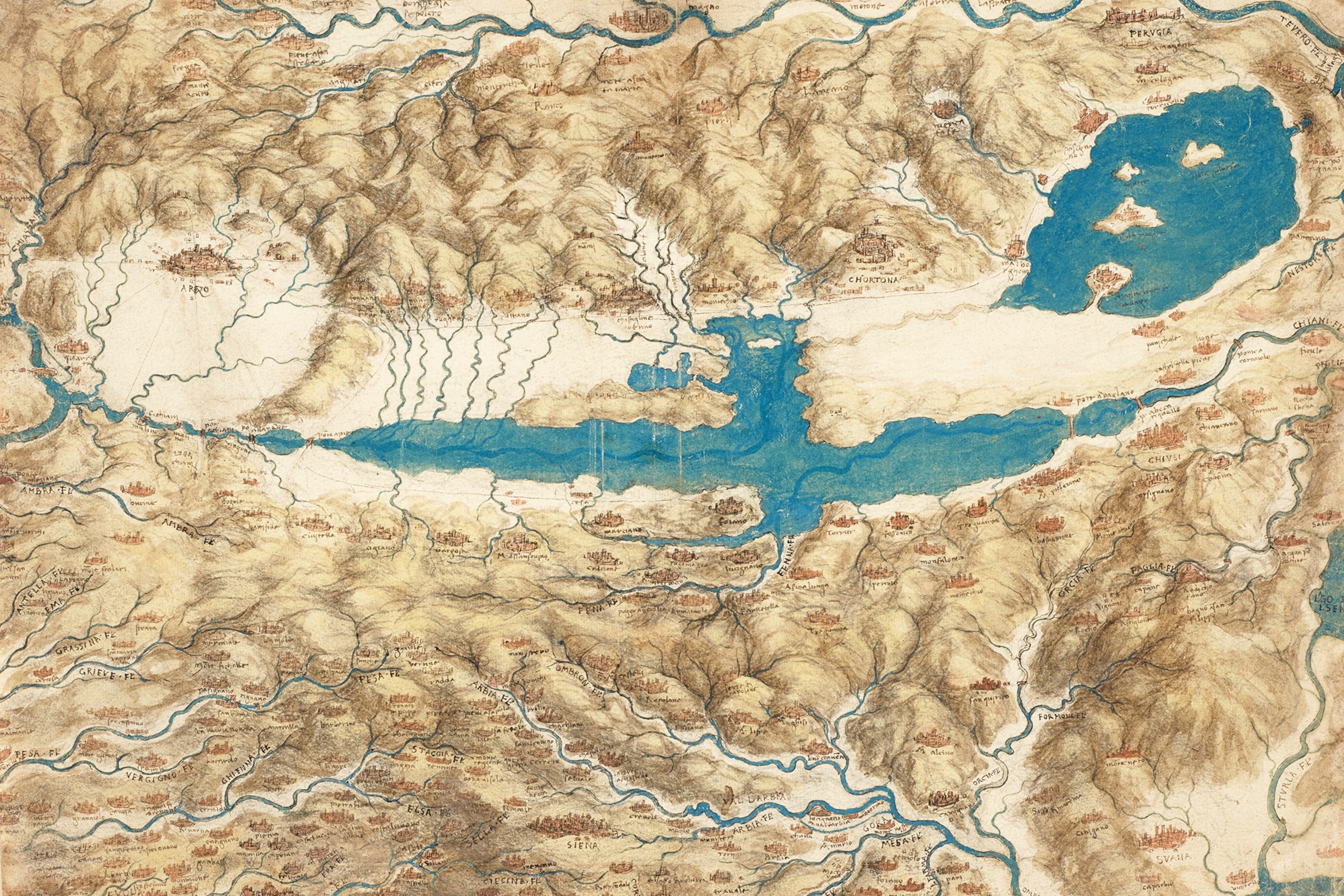

He is an artist of his time and one that transcends his time. He is very ambitious. It’s important to remember that although Leonardo was a “disciple of experience,” as he called himself, he is also paying great attention to the sources of his time. After having devoured and looked at and bought many books, he realizes he can do better. He really wants to write books, but it’s a very steep learning curve. The way we should look at his notebooks and the manuscripts is that they are essentially the raw material for what he had intended to produce as treatises. His great contribution is being able to visualize knowledge in a way that had not been done before. (See what made Leonardo a genius.)

Why is Leonardo’s handwriting significant and how did it help you understand him?

One of the myths about Leonardo’s manner of writing, right to left, is that this is code. It really is not. It’s actually quite easy to read his handwriting without a mirror. Paleography, the study of handwriting in Leonardo’s manuscripts, is very important to me. You can see that he has a rhythm of the hand—he writes quite fast, all the letters have ligatures. The hand of the artist on paper is absolutely crucial, because as soon as you can see process on a sheet of paper—whether it’s handwriting or drawing—you know you’re looking at authentic work. I’m very interested in process, because that it is what allows you to get into the mind of the artist.

What does the process in this drawing, Head of a Young Woman (“Study for the Angel in the Virgin of the Rocks”) reveal about Leonardo?

It’s one of my favorites. The psychological presence of the model is so vivid. Look at the control. He knows how to focus the eye of the viewer to what is important. Look at that incredible sideways gaze. The conventional way to portray portraits at the time was straight on, three quarters, or profile. Instead, Leonardo explores this elegant turn in space. Look at the tremendously economical way of sketching what is not of interest—the quickness of the hand, the modeling with parallel hatching, being able to extract something in just a few strokes. He creates this contrast between high polish and sketching. At all levels—as an image, as a work of technical virtuosity—it’s just amazing. A copyist or imitator could not do that. (Discover how to spot an authentic Leonardo painting.)

Despite his ambitions, Leonardo never published his treatises. What happened at the end of his life?

For me it was a bit of a human tragedy. The difference between his ambitions and his vision and what he’s able to actually encapsulate and make concrete is enormous. You realize that the world of the unrealized and what lies beyond is exponentially much larger than what he is able to produce. In the end, the most interesting part for me was the becoming of Leonardo. As soon as you are able to undertake this as a journey, you are following the artist in his development. I felt ultimately this humanized the genius.

What kind of impact do you hope your book will have?

It’s been a profoundly moving privilege to work on Leonardo in this very extended way and to be able to present this book at the anniversary of his death. It’s very humbling. There is a margin of error with everything one undertakes, but I would like to think that by studying his manuscripts, drawings, and paintings from the ground up, I have been able to achieve a level of authenticity that is refreshing for the literature. And I really hope that a generation of younger scholars will pick up the mantle. I see my four volumes as opening the door for future research, not the last word.