One Obsessed Musician, 299 Birds, and a Very Weird Crime

This is the true story of how a man stole hundreds of exotic birds to sell to salmon fly-tyers so that he could buy a golden flute. Really.

When Kirk Wallace Johnson, author of The Feather Thief, chanced on the story of how a young flute player named Edwin Rist had broken into the British Natural History Museum’s ornithological department and stolen hundreds of priceless exotic bird skins, he had no idea that he would be swept up into a world of fanatical fly-tyers, crime, and obsession that would completely take over his life.

When National Geographic caught up with him by phone in Washington, D.C., he explained how gentlemen fishermen in Victorian Britain created art while tying salmon flies; how their modern-day equivalents are willing to spend tens of thousands of dollars on feathers to decorate their lures; and how a cousin of the zany film character, Borat, became involved in the story.

At the heart of your book is a young American musician named Edwin Rist. Give us a brief biography and explain how he became involved in the world of salmon fly-tying.

Edwin is a virtuoso flautist. He was born in New York City and home-schooled, then at a fairly young age the family moved to the Hudson Valley. When he was around 10 years old, he came across a video about fly-tying and became completely transfixed by what was on the screen, racing around the house looking for materials to start tying his own flies. At the beginning it was trout flies, which are ugly-looking things made to look like real insects. He started competing in fly-tying festivals and conventions around New England. And at one of these shows, he came across the booth of a master salmon fly-tyer, who had about 60 shockingly beautiful salmon flies that employed up to a dozen different species of bird feathers, wrapped in intricate patterns around the hook. That was where something switched in his brain. He started taking lessons to master this craft, and he was amazing at it. But he was constrained by a lack of the authentic feathers. He always dreamt of being able to tie the recipes that were mapped out 150 years or so ago.

You were working with Iraqi refugees at the time. Talk about the List Project and why you became obsessed with this story.

I was formerly the coordinator for the reconstruction of Fallujah in Iraq for the U.S. government and became close to a lot of the Iraqis who were risking their lives to help us. But when I got back to the States, I realized they were now running for their lives because they are seen as traitors. In 2007, I started a non-profit to fight on their behalf. As meaningful as that was, I realized that I’d backed myself into a cause that would never end. It didn’t matter who was in the White House: Americans just didn’t want Muslims coming into the country. It became a suffocating time in my life, and the only way I could escape and get some calm in my mind was to go fly-fishing.

I was in Northern New Mexico and the guide I had hired opened up his fly box and pulled out a Victorian salmon fly he had tied. I had never seen anything like it! It was stunning! We got to talking and he mentioned this story about a kid who had broken into the British Museum and stolen hundreds of exotic bird skins to sell to Victorian salmon fly-tyers, so he could buy a new, golden flute! [laughs] There were so many elements to that sentence that were so bizarre as to be almost unbelievable. And as he was talking, some portion of my brain ignited.

Like me, I suspect most of our readers have no idea that salmon flies can generate this kind of obsession. Take us inside this arcane fraternity and introduce us to some of the legendary fly-tyers of the past and present.

For the most part, the 21st-century cohort hangs out on a few spots online, like classicflytying.com, or on Facebook groups. They also convene in real life at fly-tying festivals and conventions all over the world. These guys use the language of addiction and obsession in their posts about these rare feathers. They also observe an almost religious adherence to 19th-century texts written by Brits, like George Kelson or Major John Popkin Traherne.

One of the most famous flies is Major Traherne’s “chatterer.” It has so many feathers from what fly-tyers call “the blue chatterer,” and there’s such a scarcity of these things, you need about $2,000 in order to tie one. But no one would look at this and think it resembles anything from the natural world. The overwhelming majority of the 21st-century fly-tyers, like Rist, have no idea how to fish. This is a man-made creation designed to attract the respect of other men.

Rist stole the feathers from The Natural History Museum at Tring, in England. Take us inside the crime scene.

We use shorthand, but he actually stole the birds, then plucked the feathers from them. The Natural History Museum in Tring is the second-largest ornithological collection on the planet. It is an extraordinary place, representing hundreds of years of collecting and generations of curators protecting these things. During the Blitz, the main museum in South Kensington was hit 28 times, so the curator marshalled a fleet of unmarked trucks and secreted Russell Wallace’s and Darwin’s birds out in the cover of night to the newly acquired Rothschild Museum in Tring.

How did Rist get in there? Wasn't there a lot of security?

There was a security guard, but he didn’t find Rist that night. An alarm apparently went off in a different part of the museum, but the guard didn’t hear. There is also dispute over whether he was watching a soccer match at the time, which the museum denies.

Edwin had cased the museum previously, gaining access under false pretenses by posing as a student photographer. He used the opportunity to take photos of a lot of the birds he would later steal. He also photographed the hallways and locations of each cabinet, as well as entry and exit points, to plot his heist. Over the next seven or eight months, he mapped out what he would need, creating a Word document titled “PLAN FOR MUSEUM INVASION.” He also prepared a shopping list of things he’d need, like a diamond-glazed glass-cutter, a wire-cutter, thousands of zip-lock bags to sell the stuff to the fly-tyers once he got it, and a pair of latex gloves he stole from his doctor.

On the night of June 23, 2009, he performed at a concert in London, boarded the train up to Tring, which is about a 45-minute ride, dragged this empty suitcase up a dark alley that runs directly behind the museum, climbed up, snipped away the barbed wire, then tried to cut the glass away. He didn’t succeed, so he ended up bashing it out with a rock. He then wedged the suitcase through the opening, climbed in and was there for hours stealing 299 of these birds.

He lost track of time to such an extent that he missed the last train back to London, so had to spend the night a couple of miles away from the scene of the crime with about $1 million worth of birds in his suitcase, nervously hoping no one would descend upon him.

In all, Rist stole hundreds of thousands of dollars’ worth of bird skins. But for their guardians at Tring, it wasn’t about money, was it?

This is where the gears shifted in my own investigation. At the beginning, I thought this was just a quirky bird theft story. But the Tring collection has contributed immensely to research. We now understand, for instance, the impact of DDT pesticides from our ability to compare eggs at the collection from before the introduction of DDT to immediately afterwards. Scientists then demonstrated that eggshells had grown thinner and less viable, which led to the banning of DDT. More recently, a study of 130 years of sea birds has demonstrated rising levels of mercury in the oceans, which affects not just fish and birds, but also humans.

What animated my whole investigation was that these birds held answers to questions that scientists hadn’t even thought to ask yet! We have no clue what technologies are going to exist in 100 years to allow us to interrogate the same birds that Wallace interrogated. And so Rist blew a huge hole in the scientific record.

Some of the most valuable feathers Rist stole were bird of paradise feathers brought to England in the 19th century by Alfred Russel Wallace. Tell us about those.

Wallace is kind of famous for being not famous! In the book, I wanted to give the reader a sense of the extreme lengths that he had gone to to gather these things. He was also obsessed, but for completely different reasons. He wanted to find and collect these things in the service of human knowledge and future research. One hundred and fifty years before the heist, Wallace described the specimens he had collected as individual letters in the volume of the Earth’s deep history; and if we allow these things to disappear we’re essentially blinding ourselves to these records of the past. That’s what led him to implore the British Government to fund and preserve these collections for future generations of researchers.

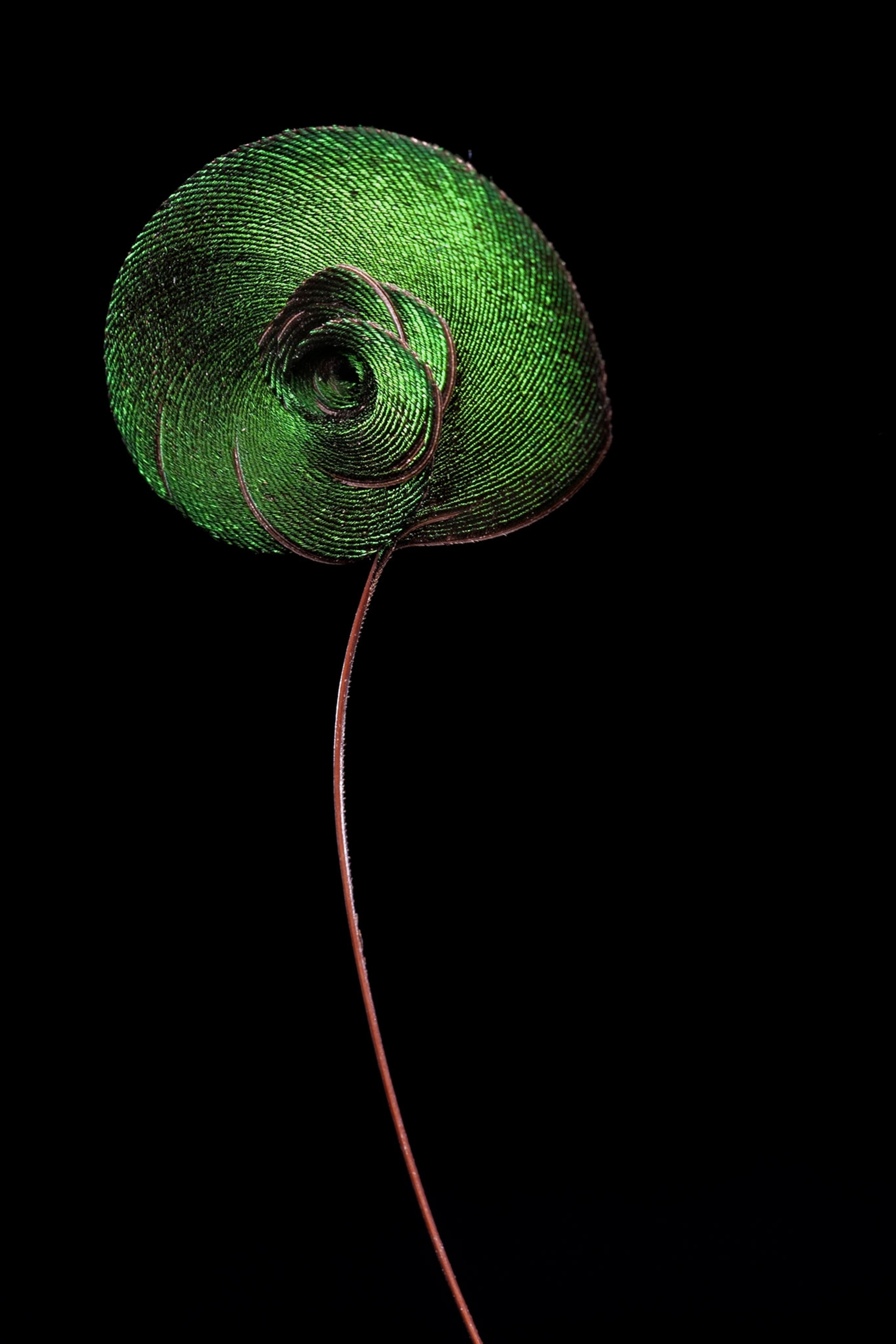

He was one of the first Western naturalists to encounter birds of paradise in the wild, like the king bird of paradise, which he found on remote islands off the coast of New Guinea. It’s a bird that is almost impossible to describe, with a brilliant red back, a white breast and these long tail feathers, at the end of which are coiled two coin-shaped, iridescent, emerald feathers. Edwin stole 37 of them.

When Wallace first saw birds of paradise, he recognized the paradox of their beauty, which he described as an almost wanton waste of it. He also realized that if people ever found these things, they would surely hunt them to extinction. That’s the nut of this whole story: whether or not we can restrain ourselves from destroying the beautiful things in nature that we’ve ascribed a value to.

Rist eventually got off scot free, after a psychologist, who is a cousin of comedian Sacha Baron Cohen, aka Borat, diagnosed him with Asperger syndrome. Many felt this was a BS defense. What’s your final take on Rist’s character and motivation?

I say this with no axe to grind against Asperger’s; I have people in my extended family who have it. But around the five- or six-hour mark of my interview with Edwin, I said, “I don’t want to sound like a jerk and I’m not an expert in it, but you don’t seem like you have Asperger’s. You’re not avoiding eye contact and you’re clearly reading the subtext of my questions.” I am paraphrasing what he told me: that he became what he needed to become during that phase in his life; that he’d never had any issues with eye contact before or since, but that all of the sudden he couldn’t look in people’s eyes, started rocking back and forth, and hiked his voice up an octave. To me, it was clear that he had gamed the system. He never spent a night in jail, graduated from the Royal Academy, and today plays the flute with orchestras throughout Germany—albeit under a different name.

When I met him, I thought he was charming. In another life, we might have been friends. I think he’s always been the smartest person in the room and that could be dangerous, given the wrong circumstances. Sometimes, I wonder why he agreed to an interview. I think it was partly because he wanted to see how much I knew, and if he could outsmart me. And maybe he did at certain points. He’s an alarmingly talented person, who let his obsessions and greed destroy a promising future.

This interview was edited for length and clarity.

Simon Worrall curates Book Talk. Follow him on Twitter or at simonworrallauthor.com.