Afghan refugees are finding a warm welcome in small-town America

An Amish refuge, a college town, and the “Ellis Island of the South” are resettling more refugees per-capita than any other U.S. cities.

It’s the first frosty day in November and a young Afghan father named Shirzad is sitting in the living room of a rented row house in Lancaster, Pennsylvania. Three former members of the Afghan National Army sit with him, fiddling with their phones and drinking tea. In Afghanistan, they guarded U.S. bases, gathered military intelligence, and interpreted for U.S. troops. Now they’ve been dropped into the heart of Pennsylvania Dutch Country, where horse-drawn buggies slow traffic and farmers peddle produce at America’s oldest farmers market.

None of these four men can return to his home in Afghanistan. As collaborators with Americans, they’re marked for revenge by the Taliban, now firmly back in control of the country. And while they feel lucky to have escaped, there’s an air of loneliness in the bare-walled house. Separated from their families, they live as roommates, sharing meals of eggs and beans, and trying to learn English.

For months, Afghan evacuees have been living in temporary camps on U.S. military bases. Now, as they move into permanent homes, some will be heading to communities with long histories of offering refuge to people fleeing danger.

But not necessarily to the bustling and multicultural cities you may imagine.

Lancaster, a quaint town of brick row homes with painted shutters, hosts the second-highest ratio of refugees in America, surpassed only by Clarkston, Georgia, and trailed by Bowling Green, Kentucky. Cities like New York and Minneapolis may absorb more refugees in total, but these three modest towns, according to the most recent figures available, take in more refugees per capita than anywhere else in the country.

In small town America, refugee resettlement programs have won over residents by reversing population declines and replenishing shrinking labor pools, data show. Religious traditions that encourage care for foreigners, as well as close-knit communities, have proved conducive to forming neighborly bonds. As one factory owner in Kentucky offered, resettlement works in Bowling Green “because we all know each other’s kids.”

Lancaster, Pennsylvania: Three centuries of refuge

Pop. 58,039 / Foreign born: 11.3% / Refugees resettled between 2016-2021: 1,605

Amish and Mennonite refugees arrived in Lancaster some 300 years ago seeking to escape religious persecution in Europe. Their descendants have been welcoming refugees ever since.

In the rented row house, the doorbell rings. Shirzad peers through the blinds. A tall, bearded man in a rain jacket waits outside with three formally dressed, blond children. The man introduces himself simply as Chris, their down-the-street neighbor, and proffers a bag of groceries.

Mismatched chairs are pulled up. Tea and pistachios are served. Chris Stoltzfus and his children squeeze onto a couch and he tells the new Afghan neighbors that he comes from a family of Amish farmers.

Shirzad had been surprised by how quiet his arrival in Lancaster had been. In Afghanistan, when someone new moves to town, neighbors cook for them all week. They linger over tea and swap stories. He’d expected the same in America. He tells Stoltzfus this, and then, wringing his hands, describes the chaos at the Kabul airport the day he was separated from his family.

Shirzad became an interpreter for the U.S. military at 17, accompanying U.S. troops on patrol just as he’d watched others do while growing up in the northern region of Kunduz. Thirteen years later, as the Taliban retook the country, he burned all evidence of his collaboration with the Americans and raced to the airport with his wife and four children. But in the scrum of people vying to get out, they were separated. He made it to Lancaster with only his eight-year-old daughter. His wife and three other children are still in Afghanistan.

“I can’t imagine,” Stoltzfus says, shaking his head. “I think about my children and having to be separated…”

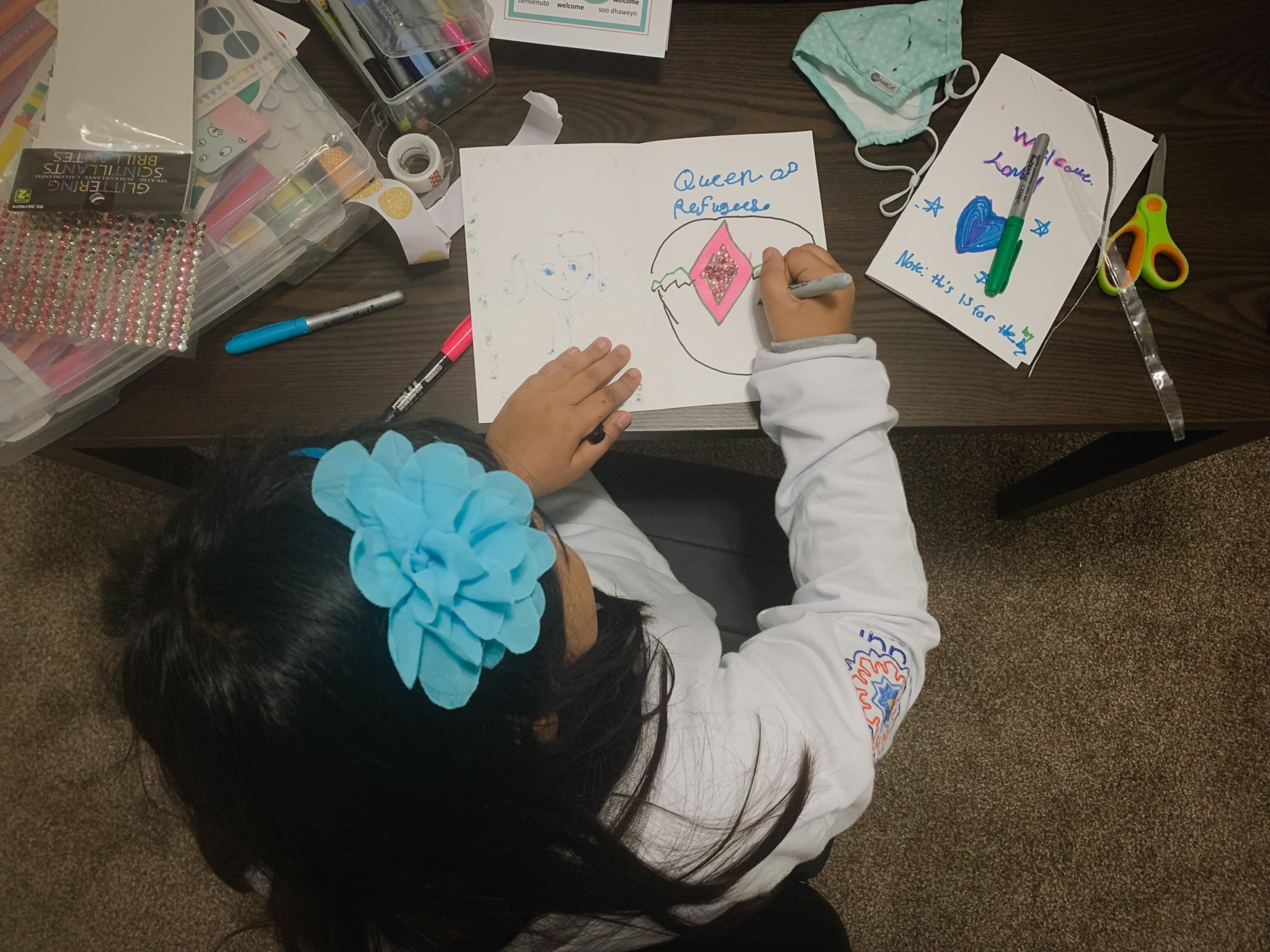

Shirzad’s daughter sits nearby, quietly coloring. The three other men look on politely, lost in the flurry of English. In Pashto, they ask Shirzad to tell Stoltzfus how happy they are to have a visitor in their home. Stoltzfus tells them about an English class hosted by his church and says he often hires refugees at his marketing firm. He invites them to come by his office.

Once the tea mugs are drained, Shirzad, who requested only his last name be used to protect his family in Afghanistan, walks Stoltzfus and his kids out. When he returns, he’s smiling widely. Seeing a face through the blinds gave him hope for this new life. “When I went to the door,” he says, “I felt like I was in Afghanistan again.”

A long pause and new arrivals

Refugees are defined as people fleeing persecution, and there are some 26 million of them in the world today. Only one percent are considered for resettlement in the U.S. each year, usually those who’ve lived for years, even decades, in makeshift camps in other countries. The admissions process involves at least a year of background and health checks, making refugees widely considered the most thoroughly vetted group of immigrants. They’re also the smallest in number.

Each year, the president and Congress decide how many refugees to let in. Since the program began in 1980, the admissions cap has averaged 95,000 people a year. But when former President Donald Trump took office in January 2017, he temporarily suspended resettlement as part of a ban on travelers from seven Muslim-majority countries; he eventually reduced the number allowed in to 15,000 people.

President Joe Biden raised admissions for 2022 to 125,000. Newly arrived refugees will be spread across willing cities and towns, which determine their capacity in consultation with local health departments, schools, and public services. Communities are preparing for an influx, but after four years of record low arrivals and a corresponding dip in federal funding, resettlement agencies must first rebuild their programs.

The practice of welcoming refugees runs to the core of Lancaster, says Jonathan Charles. His ancestors came here in 1741 from Europe, where they were persecuted for their Mennonite faith. They’re buried in a graveyard next to Habecker Mennonite Church, a small brick building on a quiet country road.

Charles’s parents spent decades helping others in the same predicament as their forebears—from Ukrainian refugees after World War II, to a young dentist from Vietnam. In 2008, they hosted a family from the Karen ethnic group in Myanmar. By then, membership at Habecker had dwindled to only 40 aging congregants. Then Karen refugees began attending services.

On a recent Sunday, the church parking lot is full. Karen language prayer books are open and Htoo Gay, a Karen leader who trades off with two American pastors, is singing hymns at the pulpit. Toward the end of the service, a petite woman stands and shares grave news from Myanmar. Two land mines exploded in her home village, she says in Karen, with an English translation projected on the wall. “Please pray for those who still remain,” she asks. A pair of Mennonite women, their hair covered by crepe fabric, squeeze their eyes shut.

Today, the congregation at Habecker includes around 25 original members, most of whom are over 70, and some 200 Karen congregants. Jonathan Charles doesn’t resent being vastly outnumbered; he’s just glad his family’s church will survive beyond his generation. “I think it’s a testimony of what we believe louder than anything we can say,” he says.

Overcoming hostility

That sense of community doesn’t always come easily. In 2017, 29-year-old Mustafa Nuur got a message on Facebook from a stranger telling him to go home. Years earlier, Nuur’s father had been murdered in Somalia for refusing to support an armed group. The family spent a decade as refugees in Kenya before arriving in Lancaster in 2014.

Nuur’s father once told him that it would be hard for anyone to hate him if they knew his story. So he invited the Facebook messenger to join him for a cup of coffee. As they talked, they discovered they had much in common: Both grew up poor, lost their fathers at a young age, and had to step up to raise their siblings. They left the coffee shop friends.

Nuur wanted others to connect across their divisions. Some Americans, he says, “feel immigrants and refugees have taken the attention of the country and the government resources. I feel I deserve to be seen here, but I also need to see these people. There’s a reason they’re hurt and upset. It’s a giant elephant in America’s room.”

In 2017 Nuur founded Bridge, a social enterprise that brings paying guests—from university students to Amish farmers—to dinner at a refugee family’s home. When Nuur noticed his guests were largely liberal leaning, he started another dinner series called Bring Your Uncle. Guests are encouraged to invite someone who’s never met a refugee before. A questions box allows attendees to anonymously ask about anything.

Nuur, who also runs a local restaurant, likes to counter fears and unknowns with facts and figures. There are many to choose from, including a 2017 government report that found over the past decade that refugees contributed $63 billion more to the U.S. economy than the government spent on them.

At one dinner, a man told Nuur he was worried that his son was getting involved in a hate group. That inspired Nuur to start a mentorship program, and now he gathers six mentees in his office once a month. He orders food and invites friends. They play games and hang out.

“I’m setting up my America for the next generation of immigrants,” Nuur says.

On a recent Friday night a group gathered in his office included two 20-something American brothers, a few Somali relatives, a recently arrived Afghan interpreter, and Mohammad Khilo, a young Syrian whose home was bombed during the Syrian civil war. As Nuur hands take-out boxes of fried rice to the group, one of the brothers tells Khilo that he’d been to a Bridge dinner at his home. Hearing the family’s story, he said, gave him goosebumps.

Bowling Green, Kentucky: A matter of economy

Pop. 72,294 / Foreign born: 12.8% / Refugees resettled between 2016-2021: 2,531

On a recent night at the Nashville International Airport, an American Airlines pilot noticed seven lost-looking Afghan men wearing blue lanyards around their necks. They spoke only Pashto, but the pilot helped them make their way out of the arrivals gate and into the arms of Hassan Eman. “Welcome to America!” Eman said in English, shaking hands with each of them.

“Kentucky?” one asked. Eman piled their bags into a white van and steered toward Bowling Green, an hour north. He dropped them at their new two-story home in a newly built development. It was only a few years ago that Eman had made the same trip, but as a passenger. He’d fled Somalia when terrorists attacked his school bus, leaving him among six survivors. Now, as an employee of the International Center of Kentucky, Bowling Green’s refugee agency, he’s often tasked with welcoming new arrivals.

The reverberations of global unrest seem unlikely to reach this quintessential college town, centered around a grassy square bordered by a marquee theater, a circa-1888 jeweler, and a coffee shop packed with students. But when the government of Myanmar was overthrown earlier this year, there were protests on the streets of Bowling Green. Every July 11, residents march 8,372 steps in remembrance of the Bosnian men and boys killed in the 1992 Srebrenica genocide.

One morning this past November, two dozen people met on Zoom to discuss the recent influx of Afghan refugees. Never before had so many come so quickly—already 90 in three weeks and 50 more on the way. The International Center staff was working nights and weekends to move them out of a hotel that offered free rooms and into permanent homes.

Albert Mbanfu, the International Center’s executive director, opened the Zoom session with a plea. “If you know anyone who’s renting a house, we’ll rent it,” he said. As is the case across much of America, Bowling Green is short on both housing and workers. There are currently 7,000 jobs open at local businesses. Without rentals, Mbanfu would be forced to place Afghan arrivals outside the city, “depriving these companies of people they need.”

Not only are the new arrivals a valuable workforce, but an industry has bloomed around resettlement, delivering an economic boost. Mbanfu’s agency injects its federal budget (around $5 million this fiscal year) into the local economy by renting apartments, paying staff salaries, and shopping locally.

Most refugees arriving from other countries had not been allowed to work in the camps where they had been living, sometimes for decades. “When they come to the U.S. and get hired and paid a wage, they feel like this is an opportunity to make up for the 20 years they haven’t been able to work,” say Mbanfu, who came to the U.S. after fleeing revolts in Cameroon in 2002.

Courting new hires

The first job a refugee gets is often “a survival job,” as it’s known, and nationwide it’s usually in meat packing. The nearest chicken processor to Bowling Green is 45 minutes away, but good pay has drawn many workers there. Now the city wants to get them back.

“There are certain companies that have aggressively recruited our refugee labor force,” says Leyda Becker, the international communities liaison for the city’s government. The pandemic, she says, along with a halt in immigration and refugee resettlement programs, as well as the retirement of baby boomers, has left positions unfilled. Competition for workers has pushed entry level pay to double the minimum wage.

Becker received so many calls from companies looking to hire that she launched a campaign to keep foreign-born workers from moving away. She proffers a flyer that reads: “From construction to manufacturing, from transportation to hospitality, Bowling Green has the right job for you!” Pictured on the flyer is a smiling man standing in front of a semi-truck. His name is Tahir “Taz” Zukic.

Zukic arrived in Bowling Green in 2000, a few years after he escaped a massacre of thousands of men in his hometown of Srebrenica, Bosnia. For a decade Zukic worked on an assembly line, then drove a truck, then bought his own. Now, on the industrial outskirts of Bowling Green, the Taz Business Center sits on Taz Court. A digital sign out front flashes “God Bless America.”

Taz Trucking was one of the first transport companies in town; now there are more than 60. Many are owned by other Bosnians, who comprise 14 percent of the county’s population.

“When you start a ball of snow down a hill, it rolls and gets bigger,” Zukic says. Today he lives in a 13,000-square-foot, French-style mansion with a movie theater. “That’s the refugee opportunity in Bowling Green.”

A global workforce

In a sprawling factory across town, the air is hazy from fire-spewing machinery. A line of Congolese workers filters in for the 3 p.m. shift past an Iranian supervisor. Above the din, it’s possible to pick up snatches of the 27 languages spoken at Trace Die Cast, where recycled aluminum is turned into auto parts.

“Foundry work has always been filled with immigrants,” says Chris Guthrie, the company president. Once they were Italian, German, and Irish. Since the Bosnians arrived in the mid-1990s, Trace Die Cast has been hiring refugees. “They’re filing the jobs that people who grew up playing Nintendo everyday don’t want. It’s hard and hot.” Refugees now make up half the 400-person workforce, and Guthrie hopes the new Afghans can fill his 80 open positions.

Guthrie says refugee resettlement isn’t a political issue in Bowling Green, but that hasn’t always been the case. At a town hall meeting in 2016, plans to resettle Syrian refugees sparked a debate so heated that police officers had to quell it. The community later agreed, but the Trump administration halted resettlement programs before any Syrians arrived.

Guthrie’s brother—U.S. Representative Brett Guthrie—supported the ban on Muslim refugees. But when the refugee admissions cap was lowered, there weren’t enough workers to run the foundry’s assembly line, and more than 100 jobs had to be filled by automated robots.

“I push him all the time about the immigration stuff, to reform the system to allow more freedom to come and go,” says Guthrie of his politician brother. As he walks through the plant, Guthrie complements his workers on their skill with complex engineering software. He asks how their kids are doing in college and tells them this country is lucky to have them. “If people think the American dream is dead,” he says, “come to Trace Die Cast.”

Clarkston, Georgia: Governing an international village

Pop. 14,756 / Foreign born: 53% / Refugees resettled between 2016-2020: around 4,000 (an estimated half of the 8,228 total refugees resettled in Georgia)

It’s a Sunday night in Clarkston, Georgia, and the Kathmandu Kitchen is buzzing. Young men clink drinks at the bar and head to a row of lottery machines. Families dig into plates of slippery momo dumplings. The restaurant is named for the capital of Nepal, but its owners are Bhutanese refugees who came to Clarkston in the early 2000s.

Waves of global crises are mirrored in Clarkston’s population. The town has been called many things: the most diverse square mile in America, the Ellis Island of the South, a refugee ecosystem, a wall-free refugee camp. Of the more than 14,000 residents who live within the town’s 1.6 square miles, about half were born outside the U.S.

In a booth at Kathmandu Kitchen, Amina Osman sips a dark beverage from a pint glass and peers down at two phones. A cameo scarf frames her face. “Mama Amina,” as she’s known, is 94 years old and originally from Somalia. She’s holding court with Ted Terry, who, in red Converse sneakers and a baseball cap, fits his press-branding as “the millennial mayor.” Osman is telling him that in the rush to resettle the newly arriving Afghans, some have been left without jackets or groceries.

“She’s like everyone’s campaign manager,” says Terry, who is now a county commissioner. Osman passes on rumors of bad landlords, black mold, fraudulent charities—things that would be unlikely to reach his ears otherwise. He takes those concerns to City Hall.

Clarkston, a historically white city, was chosen as a resettlement destination in 1980 for its proximity to Atlanta and high ratio of apartment buildings. But in 2013, when Terry became mayor, the city had placed a moratorium on refugees. There had been tensions over the use of a soccer field, and complaints that the new arrivals often walked on the roads. (With few sidewalks and without cars, they had little choice, Terry says.)

Terry ran on a safer streets platform and did something his predecessors hadn’t tried: He courted former refugees who’d lived in America for more than five years, became naturalized citizens, and could vote. He won the election and lifted the resettlement moratorium. Today, he credits that win in part to a volunteer who translated his message for the 75-odd Vietnamese voters.

“That’s a big part of politics [in Clarkston],” Terry says. “You’ve got to see the Somali elders, go to the mosque and the Ethiopian Orthodox church, and talk to the Rohingya community.”

Coffee diplomacy

This kind of small-town global diplomacy often plays out at Refuge Coffee, a gas-station-turned-cafe staffed by refugees. It sits in front of a cluster of strip malls, each filled with African restaurants, Asian groceries, and global pharmacies. This is the place to meet for do-gooders, politicians, and voyeurs of Clarkston’s spectrum of humanity.

Refugee resettlement agencies assist their clients for their first eight months in America. After that, Clarkston has nearly 140 nonprofits offering services like childcare, English classes, coding camps, and birthing doulas. But engaging refugee communities in politics remains challenging. Segregated by language and culture, refugees often don’t have the advocating power of their U.S.-born counterparts. Some don’t know how to access the system. Others fled authoritarian regimes and still fear speaking out.

Eight years after the city lifted its refugee moratorium, resettlement is far less controversial. But there are other problems on the horizon: Gentrification is creeping in and affordable housing is getting scarce. Clarkston’s future as a diverse community is under threat.

A few days before Thanksgiving, Refuge Coffee is hosting a “friendsgiving” lunch. Platters of Ethiopian injera bread steam next to trays of fried chicken. Marjan Nadir and Selina Asefaw sit at a table with heaping plates and describe growing up as children of Clarkston’s refugees. Asefaw, who was born to Eritrean refugees, and Nadir, who arrived at age eight from Afghanistan, went to work with their parents, translated for them, and learned two cultural identities. Now both are in their twenties, have college degrees, and recently returned to work in Clarkston with an organization called Refugee Women’s Network.

“One big part of feeling a part of the American community is politics,” says Asefaw, who runs the civic engagement program. Like knowing what a mayor does, she says. “I know my family didn’t know any of that. You’re focused on survival.”

When Asefaw and Nadir were growing up, Clarkston’s leadership was almost exclusively white. Today, two former refugees sit on city council and others serve on local boards and committees. Current Mayor Beverly Burks brought translators on the campaign trail and liaised with different community leaders when she ran for office in 2020. More than half the city—a record—voted in that election.

Through Refugee Women’s Network, cultural representatives are brought in front of city council to share concerns and requests—from better lit bus stops to more childcare. Before the city council election this November, candidates gathered at a local park to make their pitch through translators in front of seven different language groups.

“There was a system in their home that obviously wasn’t working,” says Asefaw. “That’s why they came here. The only way for them to know it’s working here is to see it and communicate with their candidates.”

As more people drop in, Refuge Coffee has reached a deafening decibel. Asefaw chats with Darara Gubo, a lawyer from Ethiopia and former city council candidate, about the need for better police-community relations. Commissioner Terry is in one corner, coordinating supplies for the impending Afghan arrivals. A line of new Afghan families comes in and Nadir rushes over to chat with them in Dari and help them get plates of food.

“Investing in someone new is a low investment,” says Nadir, sitting back down with a cup of coffee in hand. “And the next thing you know, they are the resources. Tomorrow, those individuals and their children are the talent pool that takes the community further.”

Nina Strochlic is a staff writer at National Geographic. Her latest stories about migration documented migrant mothers at the U.S. border and a hunger crisis in Guatemala.