Stuck at the border, migrant mothers confront a complex maze

Spurred on by rumors and false hope, women who reach Juárez, Mexico, are "the new face of migration."

Juárez, Mexico — At around 8:30 each night this past spring, some 100 people arrived at the Kiki Romero migrant shelter after having been caught trying to cross the border between Mexico and Texas. Many still wore the grey sweatpants and maroon shirts given to them at U.S. detention centers. They quietly formed a line that snaked out the building, which was previously a gym shared by the city’s high schools. Many had bloodshot eyes.

(Seeking a safe haven to grow a family)

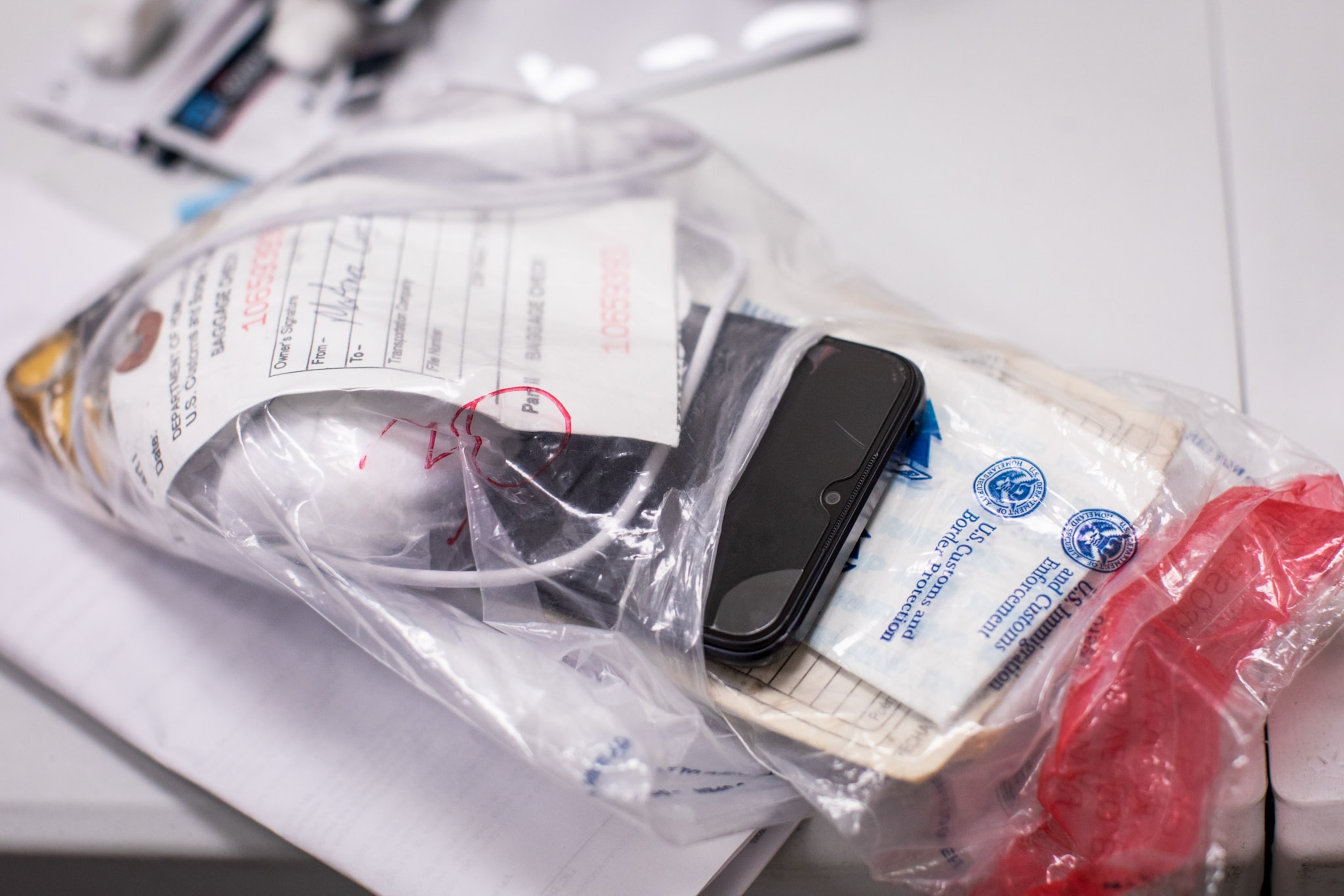

A few fathers carried toddlers in their arms, but the majority of newcomers were women and children. A mother held a baby clutching a Department of Homeland Security-branded plastic bag filled with their belongings. Another stood behind her sandy-haired son who was leaning against the wall, tears rolling down his cheeks.

One 30-year-old mother of three had stood in a line like this a few weeks earlier. Now she was volunteering at the shelter as a nurse, the same work she’d done in Honduras, so she could stay indefinitely. Like the women who were just arriving, she had also faced the crushing realization that the rumors she’d heard back home—that the Biden administration had eased restrictions for immigrants crossing the border—are far from true.

Instead, these migrants are subject to the most restrictive measures in recent memory, including a late August Supreme Court ruling that solidifies barriers for asylum seekers. And those who are denied entry into the United States must now contend with life in Juárez, one of the most dangerous cities in Mexico, where the rate of women being killed has doubled in recent years.

So as this Honduran mother administered COVID-19 tests to the new arrivals, she’d sometimes ask: Where did you cross? And when they left for a more permanent shelter, she’d exchange phone numbers with some and ask them to let her know if they eventually made it into the U.S.

For decades, young single men primarily from Mexico dominated the immigration system. Now more and more families are making the journey each month, comprising around a quarter of the apprehensions U.S. Border Patrol has made so far this year. Juárez has become a clearinghouse for this demographic. Every day, women clutch their children and cross the five bridges that connect it with El Paso—some to enter the U.S., others to walk away after being expelled.

“The migrant woman is the new face of migration,” says Blanca Castillo, a shelter volunteer in Juárez.

Convoluted policies and misleading rumors

In the past three years, policies governing the U.S.-Mexico border have become more convoluted than ever, leaving migrants, immigration lawyers, and Mexican officials scrambling to adapt. Soon after taking office, President Joe Biden ended a controversial arrangement that sent asylum seekers to Mexico to wait for their hearings, but he’s kept in place a COVID-19–related protocol that allows Customs and Border Protection (CBP) agents to expel migrants caught crossing illegally without offering the opportunity for asylum, as required by international law.

Along the entire southern border, more migrants are trying to cross than at any other time in the past 20 years. But in a given month, more than half are immediately sent back to Mexico. Since Title 42 was enacted, border agents turned back around 70 percent of the migrants they encountered.

Just a few years ago, a shelter like Kiki Romero would have been packed with two-parent families, says its director, Rogelio Pinal. This spring there were only a dozen or so staying in one corner of the gym. Nearly all the remaining space—three full sections of bunk beds at the time—held single mothers and their children.

The demand for supplies had become so great that on one bright afternoon this spring a man from the city of Chihuahua, a few hours south of Juárez, arrived with 10,000 diapers packed into a van—all donated by friends who heard about the need on social media.

In the parking lot next to the gym, where UNICEF and the city set up bathrooms and large sinks for laundry, the Honduran mother of three and two others from Honduras gathered in a tent that served as a baby changing station. Their daughters ran in and out, flopping into a pile on the changing table and twisting each other’s hair as their moms described the journey.

The shelter is set up for seven-day stays, but these three migrant mothers had been living here nearly since it opened on April 5. Its location, right next to a police station, was chosen to dissuade coyotes—human smugglers who take migrants across the border—from soliciting customers. The three women felt safe, but their world had shrunk to a single block: They could leave only to buy chips and lollipops at the tiny tienda across the street.

In Honduras, the mother of three grew up in an orphanage, got a nursing job, and then pulled double shifts to earn enough to buy a house in the coastal town of Sonaguera. But it was never enough. “In Honduras you work many, many, many hours for nothing. For una miseria,” she says, using a word that can mean both a misery and a pittance. Her three children—two daughters, age 11 and 7, and a five-year-old son—still went hungry.

Shortly into Biden's presidency, he halted a 2019 Trump administration policy called the Migrant Protection Protocols (MPP), which required migrants caught crossing the border to wait for their asylum court date in Mexico. Some 25,000 people were part of that program, and as it began to be dismantled in February, small groups were allowed to enter the U.S. (Then, in August, the U.S. Supreme Court shot down Biden's attempt to dismantle MPP, ordering the government to again send migrants to Mexico to wait for their asylum hearings.)

This, in part, has contributed to the rumors, often claimed as facts by coyotes, that the border had opened up to migrants.

“Single mothers with children are particularly vulnerable,” says Dora Giusti, the head of UNICEF in Mexico. “They heard that in Mexico they wouldn’t be separated or detained. This has probably been a push factor in taking the journey.”

When the Honduran mother heard that rumor, she sold her house and bought four bus tickets for herself and her three children. “What I want is to work,” she says, “so my kids can study, so tomorrow they can be better people than me.”

Another Honduran migrant, a 28-year-old with a high ponytail, says she heard reports on TV that entry across the U.S.-Mexico border was easy. “I thought the doors of the country would be open,” she says. “I expected to be welcomed.”

In fact the border may be more difficult than ever. Everyone in the Kiki Romero shelter had fallen into the dragnet of another Trump-era policy that has been left largely untouched by Biden: Title 42. Since March 2020 this provision in the U.S. health law has allowed for the immediate expulsion of any migrant caught crossing illegally into the U.S. Previously migrants could ask for asylum and be given a court date. Now that opportunity is rare, data shows, apparently left at the whim of border patrol agents.

Many of these mothers crossed into the U.S. from the Mexican state of Tamaulipas—currently the busiest crossing on the border. In March Tamaulipas stopped taking back deportees with young children from the U.S. Instead the American authorities began flying families caught crossing from Tamaulipas to El Paso, 600 miles away. The migrant families were then bused to a bridge and sent into Juárez on foot.

This is what happened to the three Honduran mothers. Though they traveled separately, their stories are almost identical. None had been told where they were going. “They made us feel like we were staying in the U.S.,” says the mother of three. “Then they took us off the plane and here we are.”

(The Honduran migrants requested they not be identified by name for fear that it could jeopardize their asylum requests.)

Bridges that divide and connect

From the air, Juárez and El Paso appear as a single sprawling metropolis divided by the curvy brown water line of the Rio Grande. On the ground the cities are separated by bridges, which commuters, shoppers, and students cross every day. The connection is bound by commerce and blood—most families are spread across both sides of the border. The bridges divide and connect them, and sometimes even act as a wedding venue so families and friends on both sides of the border can take part in the celebration.

Through his office window, Enrique Valenzuela has a nearly unobstructed view of the Santa Fe bridge, which connects cantina-lined downtown Juárez with the main shopping street in downtown El Paso. In the spring Valenzuela, who coordinates the Mexican government’s regional migration response, watched as U.S. officials began using that bridge to send migrant families back to Mexico. The chaos is still seared into his memory: confused young parents collapsing onto the ground in tears when they realized where they were.

At first Valenzuela and his staff brought them to the office in Juárez, fed them pizza, and helped transport them to local shelters. When he noticed that 60 percent were single mothers with young children, he knew they would need to open more shelters that could accommodate families and also acquire huge quantities of milk and diapers.

“It’s our job for this not to become a crisis,” Valenzuela says. Then he rattled off the changes of the past few years—from the migrant caravans to MPP to Title 42 during the pandemic—until he ran out of breath.

In the year after Title 42 was implemented only two percent of all migrants apprehended along the border were able to remain in the U.S. to pursue an asylum claim, according to government data.

“It’s a whole different ballgame with Title 42,” says Valenzuela. “People who are returned under Title 42 are sent back without a shot at anything. There’s nothing waiting for them here.”

Children crossing alone

The desperation under that new policy was palpable, Valenzuela says. A few months after it began, he and his colleagues started hearing alarming stories from the shelters they worked with: young mothers and fathers were sending their children across the border alone. They had never heard of this before.

Families caught crossing were being returned to Mexico immediately, but unaccompanied children were absorbed into the U.S. detention system and then transferred to the custody of relatives across the nation. For some parents, sending their child across the border was the only way to complete a journey that had caused so much hardship and cost so much money.

In March 19,000 unaccompanied children were found traveling alone across the border—the highest number ever counted. Many of them, CBP discovered, had previously tried to enter with a parent but had been expelled. (CBP has not since tracked this figure.)

In Juárez unaccompanied minors cross in plain sight.

The Chamizal park, with low trees and picnic tables, is a popular weekend gathering spot for Juárez residents. Past the park is a highway, and then beyond that is the Rio Grande, which serves as the natural and legal border between the U.S. and Mexico. The shallow, murky water flows through a sloping channel that was laid in cement to prevent the river from changing course and thereby altering the marked border.

This part of the border used to be so porous that students at the El Paso high school directly across from the park could watch migrants slip through the fence and race through the school’s courtyard. No longer. Beyond the river channel now is a narrow road where white CBP trucks often patrol, and then a towering border wall.

This is where some migrant mothers have sent their children to illegally cross into the U.S. side of the border on their own.

This was a decision made by a group of Central American mothers who lived in a rental house on the farthest western edge of Juárez, where the roads turn to sand and stray dogs run wild. Each woman had traveled to Juárez separately, driven by threats from boyfriends and gang members, or by the hope of a job. They had sought asylum in the U.S. and been returned to Mexico to wait for their asylum hearings. Soon the COVID-19 pandemic canceled the women’s court dates.

One night, in the government shelter where they met, gunshots echoed outside and soldiers rushed in, telling them to get under their beds. They decided to leave. A Honduran woman at the shelter told them that if they tried to cross the border with their children, they’d all be returned to Mexico. But if just their children went, they had a shot at getting into—and staying—in the U.S.

In August 2020, the mothers and their kids moved into a rental home together and soon after, on a hot morning, a Guatemalan mother walked her 13-year-old son though the Chamizal park and to the banks of the Rio Grande. She gave him his birth certificate and the phone number of his grandfather in South Carolina. Then she watched as he turned himself in to border patrol agents in a passing CBP vehicle.

A few days later two more mothers brought their daughters to the border to do the same. Both women fled from the Indigenous highlands of Guatemala, where decades of conflict, hunger, and drought have pushed thousands of people to the U.S. border each year. Both mothers have the same first name, Santos, but they called one—a petite mom who looked much younger than her 30 years—by the nickname "Santita."

Santita says she waded into the Rio Grande with the two girls. She told her seven-year-old daughter to give Border Patrol agents the names of her father and sister, who work in a coastal town in Oregon. “Trust me,” she says she told her daughter. “You’ll be with family.”

As la migra approached, Santita hurried back to the riverbank in Juárez. From there both Santos and Santita watched as a passing Border Patrol agent put their daughters into the patrol truck. Neither regretted what they’d done. “I wanted us to go in together, but it didn’t turn out that way,” Santita says.

Eight months later, as MPP was dismantled this spring, the mothers left the rented house and each managed to enter the U.S. to wait for their asylum dates with their families.

‘A last attempt at life’

Karina Breceda knows what goes through a mother’s mind when she decides to send her children across the border alone. Breceda is a fast-talking fronteriza, as those who grew up in the borderlands sometimes call themselves. Every morning she commutes from El Paso to Juárez and often she stays late, volunteering to pick up new arrivals at the bridges and drop them off at shelters. She helps run the shelter at San Juan Apóstol, a local Catholic parish that houses only migrant women and children.

This spring, as the U.S. sent more families to Juárez from other border crossings, Breceda took note of the worsening condition of the newcomers. There were mothers with toddlers who hadn’t showered more than a week. They were dehydrated and wearing clothes caked with mud. Some had soiled pants because they’d been denied sanitary pads in detention. Others had stopped producing breast milk due to dehydration. Their children had strep throat and concussions. “This is the first time I’ve seen so many vulnerable women,” she says.

In the magenta-hued office of the shelter’s volunteer psychologist, women describe being raped, kidnapped, and abused in front of their children on their journey to the U.S. Adding to the danger, Breceda thought, was the fact that some of those being expelled were sent back over the bridge as late as 11 p.m., on a street packed with seedy bars in a city known to be deadly for women.

So when they send their children into the U.S., Breceda understands. “They tell me that it feels like a last attempt at life,” she says, “a last grasp at a rope when they’re falling.”

Following a mother’s footsteps

Juárez has become a dead end for many of these women. As the U.S. border tightens, the number of migrants requesting asylum in Mexico is rising. In the shelters, they wait for a change in policy or the right moment to try crossing illegally again. With luck and determination, some are able to complete their journeys.

When Ivana Turcios was six, her mother Ana packed a bag and left their home in Honduras for the U.S. By the time Turcios saw her again, over video chat a decade later, she was surprised by how old her mother looked. Turcios was already married by then, and soon had children of her own.

Turcios, now 21, left Honduras to escape her ex-husband, who she says abused and threatened her. In March, Turcios got custody of her three-year-old son, Sneijder, and left Honduras, leaving behind a six-year-old daughter, who lives with her ex. She boarded a series of buses that would take her across three borders and to her mother in the United States.

Like many others, the pair was caught and sent back to Mexico, where they ended up at a migrant shelter in Juárez called Pan de Vida—bread of life. Small bungalows encircle a large sandy courtyard where kids play on jungle gyms. Inside, partitions of sheets and curtains offer a little privacy to the 260 residents.

This is where Turcios met Linda Rivas, the director of an El Paso-based immigration law firm, who applied for humanitarian parole for Turcios to enter the U.S. The criteria was murky, but recently Rivas had gotten in a child with cerebral palsy and a 38-week-pregnant woman. Now she would try with Turcios and her son, who has epilepsy.

The gamble worked. Turcios was elated. On the day she was to leave Juárez, Turcios met Rivas at the entrance to one of the bridges that stretched over the towering border wall and into El Paso. She had packed two small backpacks with a change of clothing and Sneijder’s epilepsy medicine. She’d carried nothing else from Honduras; all evidence of her former life was held on her phone.

Her mother would be waiting for her in Chicago. Once there she’d still need to argue her asylum case in court. But that’s not what Turcios was thinking about as she prepared to leave Juárez the night before: she was nervous. She had children of her own now, but she hadn’t had a mother in 15 years. “Maybe she will treat me like I’m six,” she said. Then she smiled. “It doesn’t matter.”

That smile faded quickly as she wondered if she’d ever see her daughter again. The last time they spoke on the phone, her daughter cried and asked why she’d left. “I tell her that her brother’s sick, what else can I do?” she said. “I’m hoping when she gets older she’ll understand the truth of what happened.”