See Beijing in This Incredibly Detailed, Hand-Drawn Map

Artist Gareth Fuller spent a year walking the streets of Beijing, meticulously drawing a map of the city as it exists, and as it could look in the future.

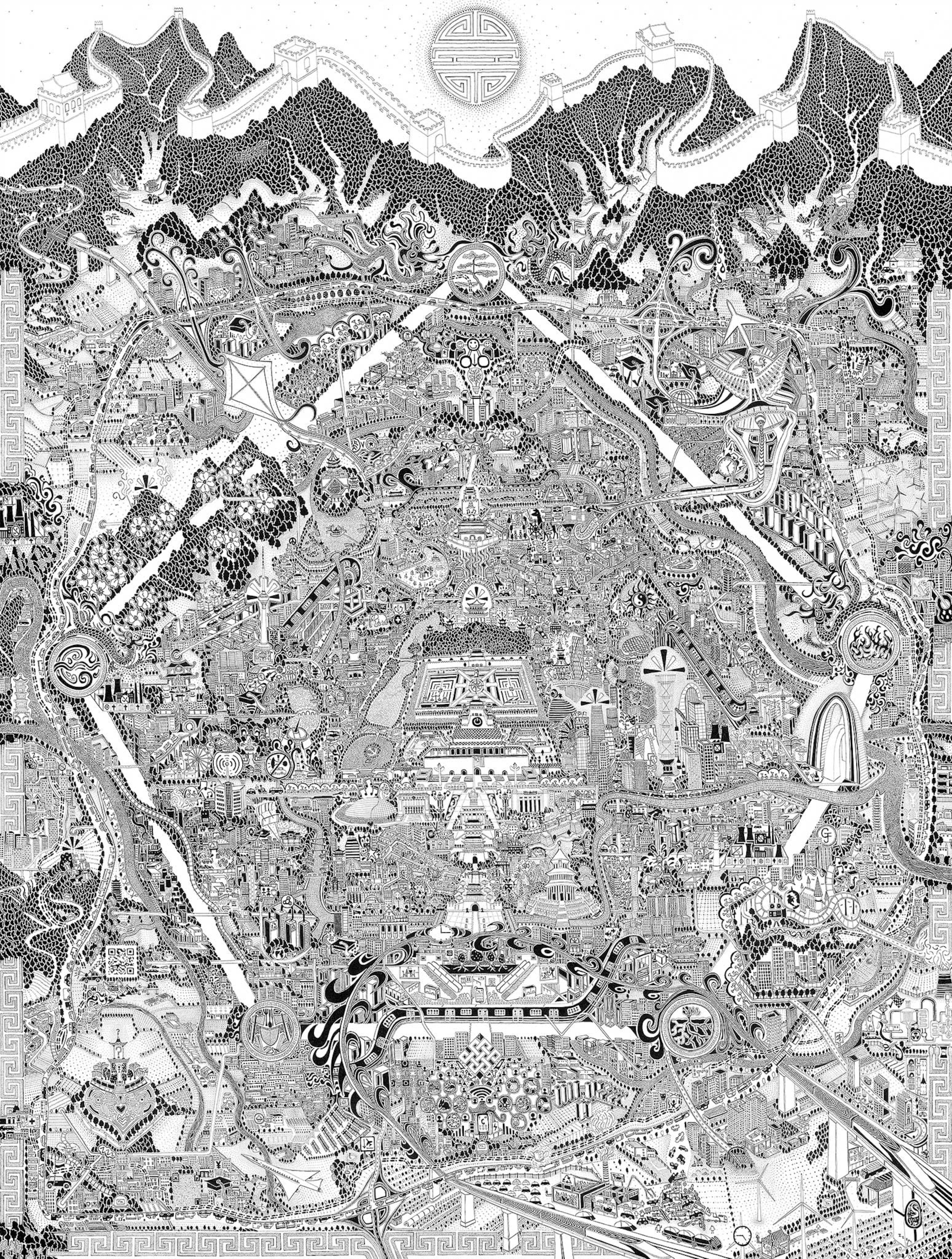

British map artist Gareth Fuller spent a year walking and bicycling the roads and back alleys of Beijing, logging more than 800 miles and 1000 hours of drawing time to make this remarkable map. It’s filled with playful details that capture the Chinese capital as it exists today, and as it could become.

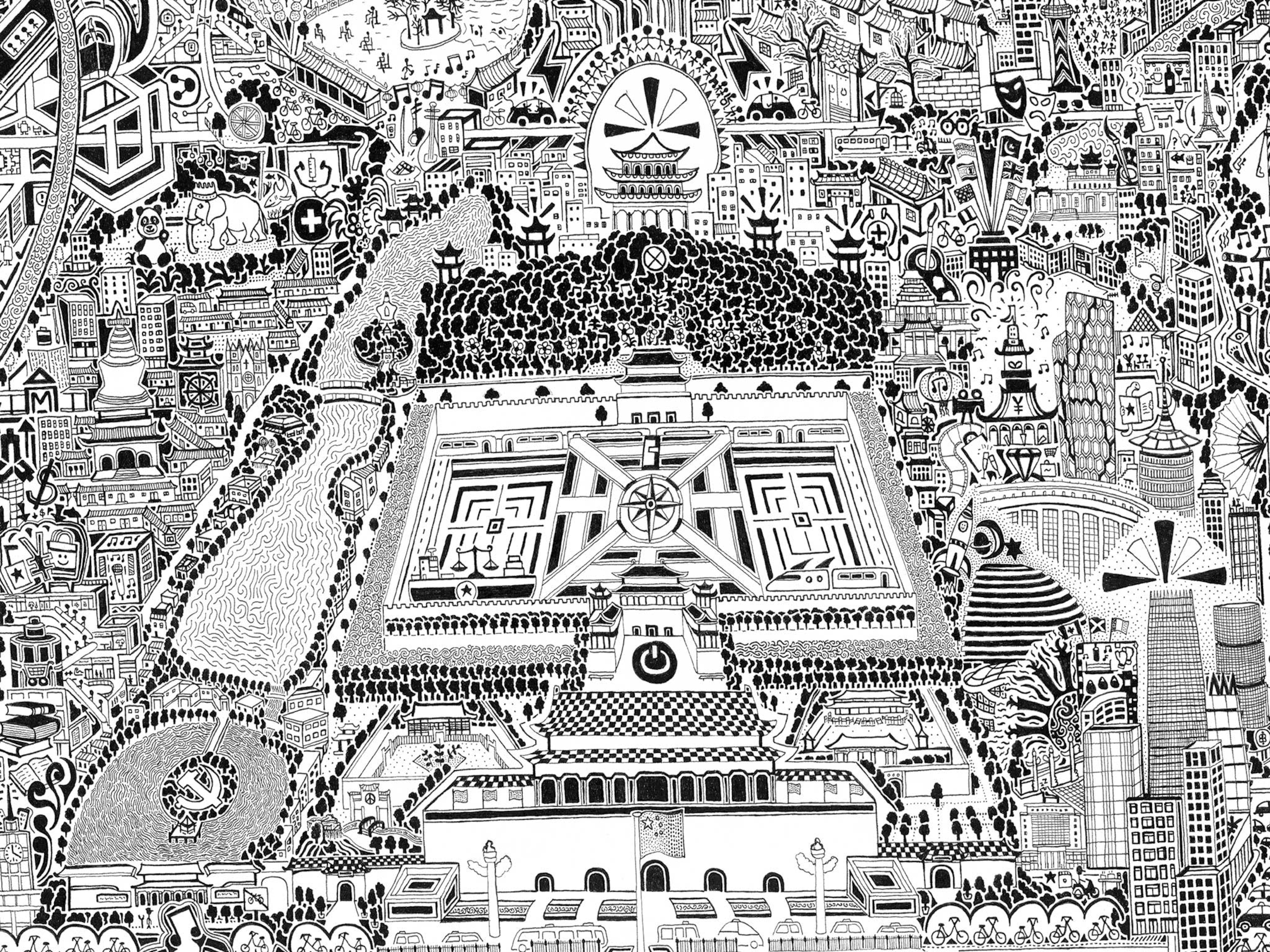

The map, roughly four feet wide and five feet tall, is loosely organized around real landmarks, like the concentric “ring roads” emanating from Beijing’s center, but much of the space is distorted to accommodate scenes inspired by Fuller’s exploration. After some preliminary sketching in pencil, he mostly draws in black ink. Mistakes can’t be erased, but Fuller says he tries to use them to inspire new ideas. “A mistake can often be excellent,” he says.

Fuller is best known for his 2005 work, “London Town.” That map was a decade in the making, and it’s filled with sly cultural commentary and hidden references to Fuller’s personal encounters and experiences in the city. “Beijing” charts the city through a personal lens as well, though this time through the eyes of an outsider trying to get a handle on a frenetic foreign city and its culture.

Fuller says he made a deliberate choice not to do extensive study before moving to Beijing in 2017 because he wanted to get to know the city firsthand. “I basically threw myself in the deep end,” he says. His explorations often took him to places foreigners don’t typically go, like the busy ring roads that surround the city and the back alleys of the inner city. “As a white guy walking along these busy roads in flip flops I was definitely out of place,” he says. But despite a few curious looks, he says, “people were incredibly friendly and welcoming.”

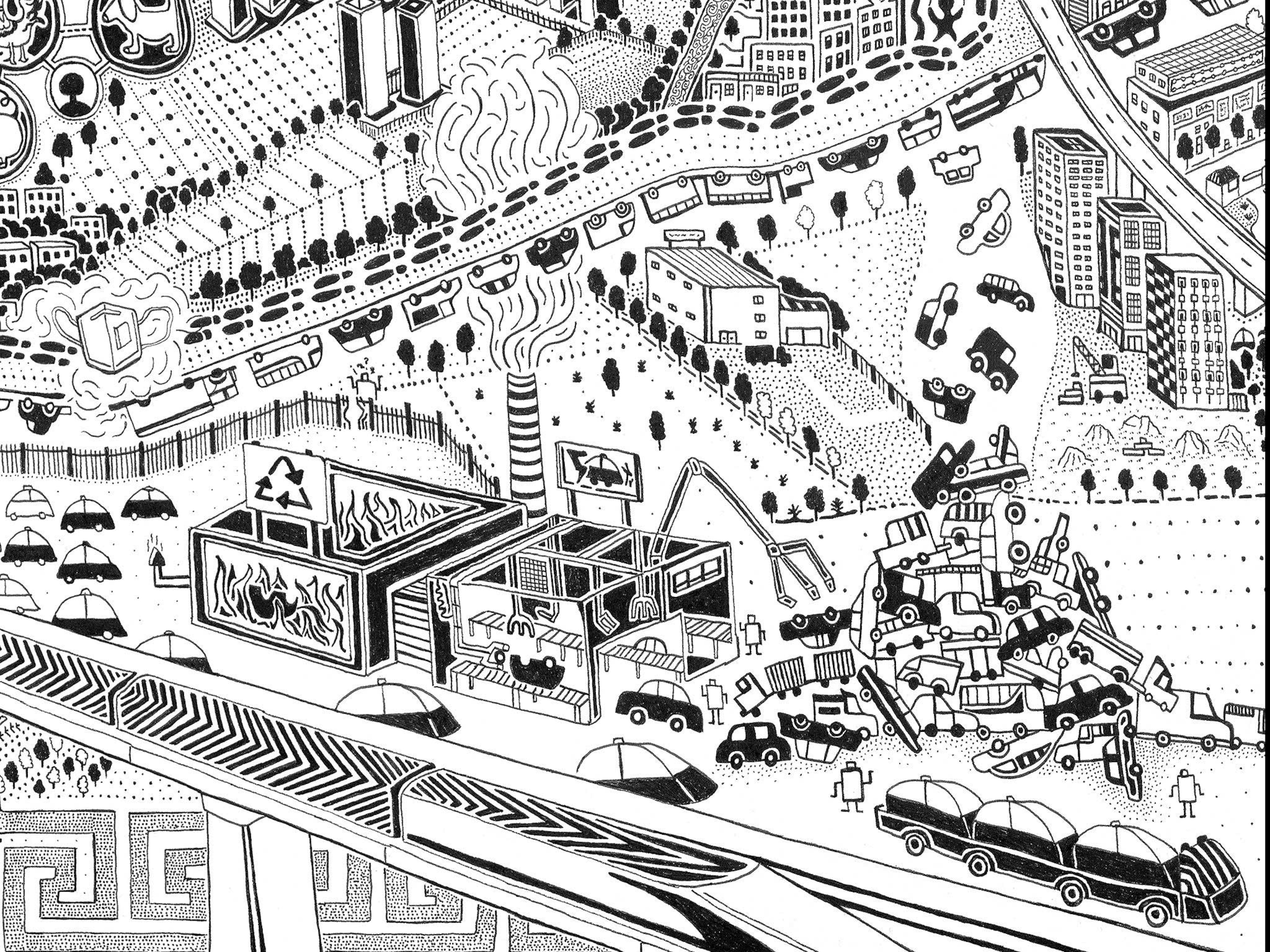

Fuller’s map of Beijing depicts a hopeful, if speculative, vision of the city’s future, where factories run by robots recycle conventional vehicles into electric ones and wind farms and nuclear power plants running on thorium generate power. Drones deliver packages of fresh vegetables grown on tiered platforms on the edge of the city (see the gallery above).

That’s not to say the map completely ignores the present reality. One river runs black with pollution; elsewhere a factory fence is lined with tombstones. Construction cranes symbolize the city’s building boom, which has displaced many people, especially immigrants, from the inner city, and a brick wall represents the city’s policy of closing down unofficial businesses in the hutongs, or back alleys, by bricking over their entrances. Other details highlight the intersection of ancient and modern traditions, from ancient Buddhism to the modern obsession with technology and wealth.

Fuller says his time exploring the city made him more aware of how cities and the natural world are interconnected. But it also inspired him to imagine a better future instead of dwelling on the pollution and other current problems. “The future could be bleak enough without me drawing it,” Fuller says. He hopes his more optimistic portrait of the city will inspire discussion about potential solutions. “China feels like an enormous experiment,” he says. “Whatever they do is important for the future of the planet.”

Greg Miller and Betsy Mason are authors of the forthcoming illustrated book from National Geographic, All Over the Map. Follow the blog on Twitter and Instagram.