The oldest known city map is startlingly precise

It took decades for archaeologists to realize this 3,500-year-old tablet depicts an ancient city at scale. But how did its creators pull that off?

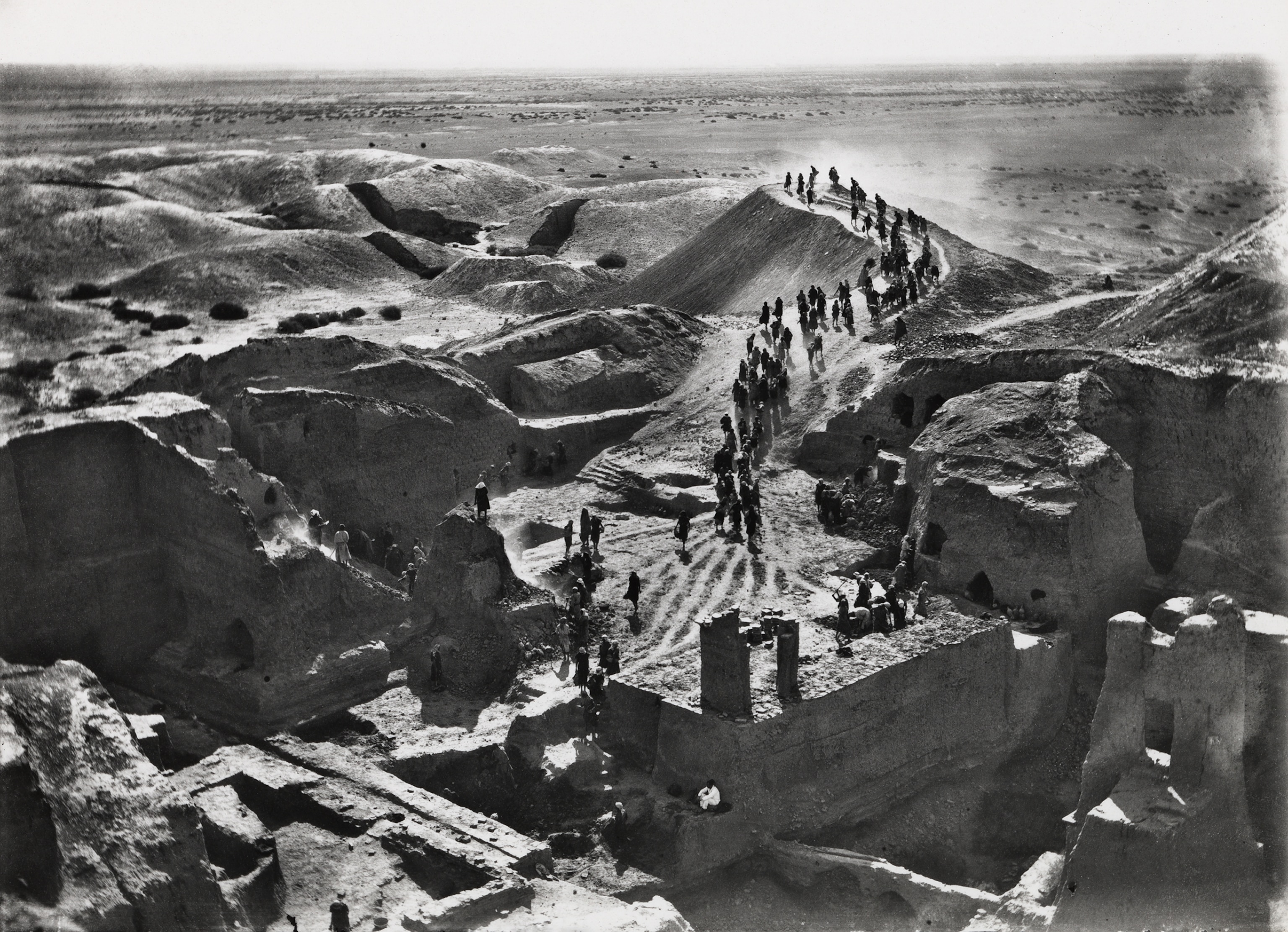

One of the world’s oldest maps was etched into a clay tablet likely sometime between 1500 and 1300 B.C. And ever since its discovery, during an 1899 excavation in what’s now Iraq, scholars have argued over how to read it. A bit larger than an adult hand, the map shows distances between gates in the wall surrounding the Mesopotamian city of Nippur. But to some archaeologists’ eyes, the locations of structures on the tablet didn’t seem to align with the city’s excavated remains.

Many experts believed the map was simply off—until the 1970s, when University of Chicago archaeologist McGuire Gibson came across aerial photos of Nippur and thought he could pinpoint where the map showed city walls jutting south. When excavations there revealed traces of fortifications, Gibson realized the map’s lines and angles “fit beautifully” with what he was uncovering. Oriented correctly, the map covered the whole city, an area of roughly half a square mile, and it was precise to within 10 percent.

No one knows for sure how its creators achieved this level of accuracy—or why, given that ancient people weren’t lugging around stone slabs to navigate. We know Mesopotamians were savvy land surveyors, as other unearthed tablets include detailed renderings of farm fields and housing plots useful for things like tax assessment, says Augusta McMahon, University of Chicago professor of Mesopotamian archaeology and director of the school’s Nippur excavations. But the Nippur tablet covers a far larger area. Its creators likely used rudimentary surveying tools, like knotted ropes and rods, and maybe also a form of trigonometry for calculating angles. But making the map would still have required laborious, incremental measurements and patient tabulation.

One clue to the map’s possible purpose emerged as historians realized that, in the centuries before it was etched, Nippur had been largely abandoned. Then a new line of kings, from a people called the Kassites, took power. According to Johannes Hackl, professor of Assyriology at Germany’s Friedrich Schiller University Jena, where the tablet is held, Mesopotamian rulers felt a “duty to be builders”—and we know the Kassites set about rebuilding parts of Nippur that had crumbled. What you’re looking at might be not just a map but a blueprint: the world’s oldest city plan.