California Gets Tough on Widespread Use of Antibiotics in Livestock

California is about to become the first place in the United States to put tough legal restrictions on the ways farmers can give antibiotics to livestock, going far beyond what new federal rules allow.

The controls come courtesy of a law that has been sent to Gov. Jerry Brown, which he will sign by Sunday. Bill 27 (prosaically titled, “Livestock: use of antimicrobial drugs”) represents the only legislation ever enacted in the U.S. that puts enforceable limits on antibiotic use, gives a state agency oversight of how farmers use the drugs, and prescribes fines if they go beyond what is allowed. (Update: Brown signed the bill one day after this was published, Saturday, Oct. 10.)

That’s a big advance. True, a number of cities (Seattle, Cleveland and Pittsburgh, among others) have passed resolutions supporting cutbacks in routine antibiotic use in meat animals—but since most meat animals aren’t raised within city limits, those resolutions are mostly symbolic. And yes, at the federal level, the Food and Drug Administration recently launched a voluntary program that should constrict what farms are permitted to do—but it exerts that control by asking for changes from antibiotic manufacturers, not their users.

The California program isn’t at all symbolic, and it aims straight at users and prescribers of antibiotics: farmers and their farm veterinarians.

“The law is a game-changer,” Avinash Kar, a staff attorney at the Natural Resources Defense Council, tells The Plate by phone. “It instantly puts California at the forefront of U.S. efforts to end livestock misuse of antibiotics.”

To understand how California’s new rules are different, here’s a brief primer on how antibiotics are used in meat animals. It’s a spectrum. At one end, animals get antibiotics when they are sick, just as humans do, or when there is diagnosed sickness in the herd or flock. At the other end, they get much smaller doses of antibiotics—far too small to cure anything—for “growth promotion,” which makes animals grow muscle faster, so that they get to sale weight with less feed or in less time. (Sometimes that is called “feed efficiency.”) In the middle, there’s a category called prophylaxis or “disease prevention and control,” which uses medium-sized doses to prevent disease from occurring—but those doses, like growth-promotion doses, are administered routinely in food or water, and are given whether any diseases are happening in the animals or not.

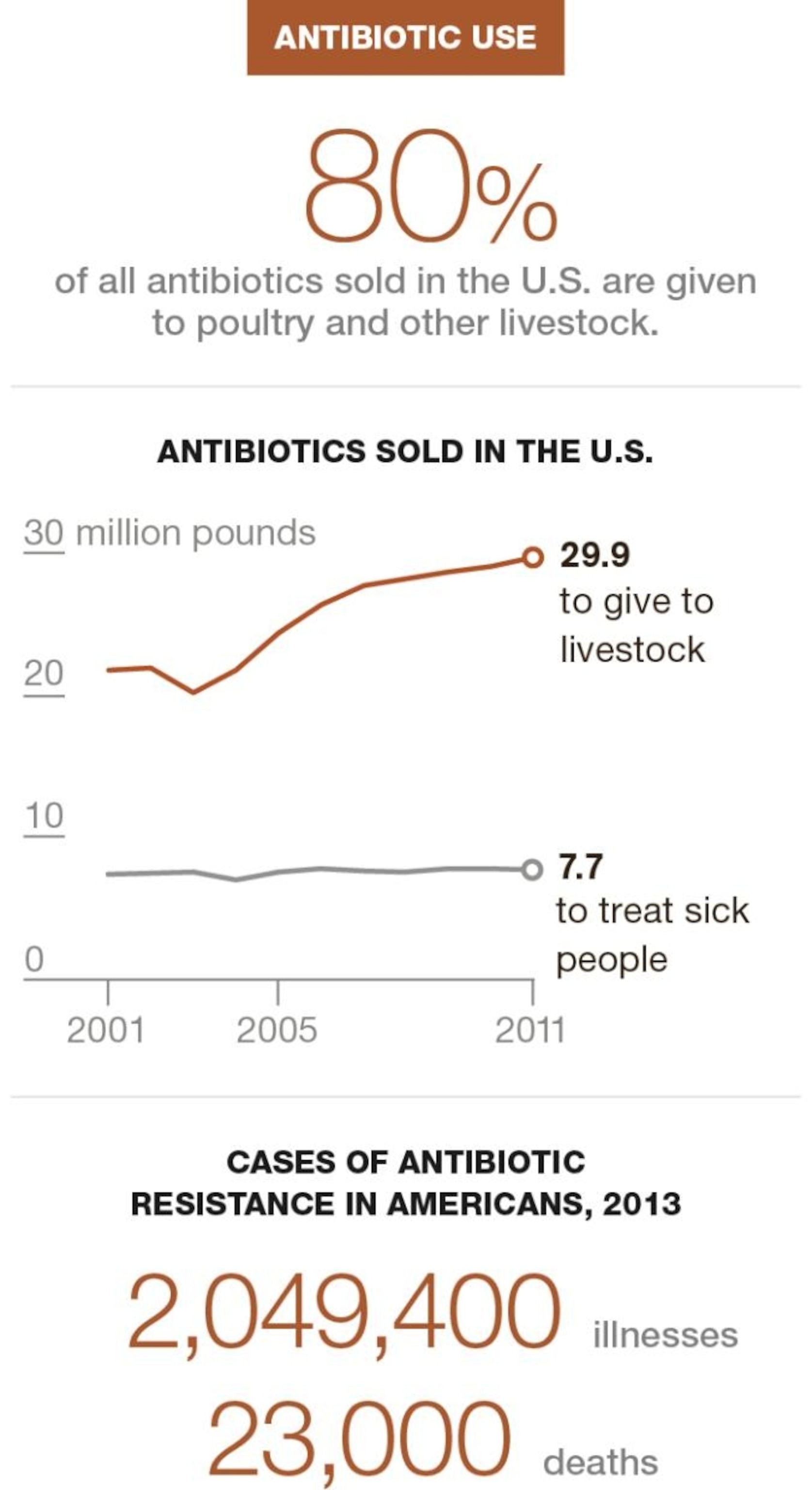

(How much is in which category? That’s hard to say precisely, because the FDA doesn’t currently ask for data that would let us know. But parsing the data that it does receive and publish, the two non-treatment categories, growth promotion and prophylaxis, probably comprise at least 90 percent of the farm antibiotics sold each year.)

Growth promotion, and also prophylaxis, go against the most important rule that governs antibiotic use in human medicine: to only give the drugs for an illness that they can affect. That is, in human medicine, we prescribe medicine only when someone is sick. But growth promoter and prophylactic doses go to animals that are not sick. By definition, they are a misuse of antibiotics’ power. And for decades, some portion of the growing problem of antibiotic resistance has plausibly been traced to that misuse on farms.

The major agricultural antibiotic-control programs, though—the FDA’s voluntary program, and the European Union’s 2006 ban—only aim at growth promoters. That’s where the new California bill is different. It prohibits both growth promotion and prophylaxis. Which means it could do more to control antibiotic use in livestock raising than any other program that has been tried.

Here’s what the bill specifies:

- It forbids growth promotion.

- It allows antibiotics to be used for any recovery from surgery, to cure cases of diagnosed diseases, or to prevent the spread of a diagnosed disease.

- Except for those three specific examples, it disallows administering “a medically important antimicrobial drug in a regular pattern.”

And that last clause describes routine prophylactic use.

“The bill is exciting on two fronts,” Laura Rogers, deputy director of the Antibiotic Resistance Action Center at George Washington University, tells The Plate. “First, it disallows use of antibiotics for routine disease prevention, which FDA’s new policies chose not to tackle. Second, it requires the state to collect information on how and why antibiotics are used in meat production. Right now we don’t have that depth of information.”

The bill also mandates other things that go beyond what the federal government is pursuing. As in the new FDA program, it requires that farmers have an ongoing relationship with a licensed veterinarian, and use only drugs that have been prescribed by that vet. But it also allows the state to request and review that paperwork, which the FDA has so far not committed to doing. And most strikingly, it imposes specific fines—$250 per day for a first violation, and $500 per day for subsequent ones— if the law is not followed.

Unlike California’s 2014 “cage-free law,” which mandated that all eggs sold in the state come from chickens given specified amounts of living space, this new law won’t affect meat animals raised beyond the state’s borders. It’s still likely to be influential.

First, because, though we think of California as the nation’s produce section, the state also boasts significant meat production. According to the U.S.Department of Agriculture’s Economic Research Service, California is the country’s biggest dairy producer and third-leading state (behind Iowa and Texas) for beef cattle. It produces 5 percent of US milk, beef cattle, and chicken eggs, and because of the new law, the lives of all the animals responsible for those products will change.

Second though, and maybe more important, California has always been a place that sets trends for the rest of the country to follow. Though the U.S. lags far behind Europe in controlling routine farm-antibiotic use, opposition to the practice has been building for a while: in school systems, in hospitals, among chefs and outspoken mothers, and in forward-thinking restaurant chains such as Chipotle and market-moving ones such as McDonald’s. California’s law could be the lever that tips those consumer movements into a national consensus. It will be worth watching to see.