What your mouth can reveal about your health

Scientists are discovering that the oral microbiome—home to hundreds of species of bacteria and fungi—may help predict everything from cancer risk to heart and brain health.

More than a millennium ago, the Persian physician Avicenna suggested that oral maladies could affect the entire body. Today, modern research is showing just how far those effects may reach—revealing that the microbes living on our teeth, tongue, and gums could offer clues to the early detection and prevention of disease throughout the body.

A recent study in JAMA Oncology found that 27 species of oral bacteria and fungi were associated with a 3.5-fold higher risk of developing pancreatic cancer. Using whole-genome sequencing, researchers discovered that patients with evidence of certain microbes in their mouths were significantly more likely to be diagnosed with the disease.

“By profiling bacterial and fungal populations in the mouth, oncologists may be able to flag those most in need of pancreatic cancer screening,” says study co-senior author Jiyoung Ahn, director of the Epidemiology and Cancer Control Program at NYU’s Laura and Isaac Perlmutter Cancer Center.

These findings reflect a broader shift in how scientists view oral health—not as an isolated concern, but as a window into systemic health. “It starts in the mouth, and it evolves, impacting the gut,” says Marcelo Freire, a dentist and associate professor in the Genomic Medicine and Infectious Disease Department at the J. Craig Venter Institute.

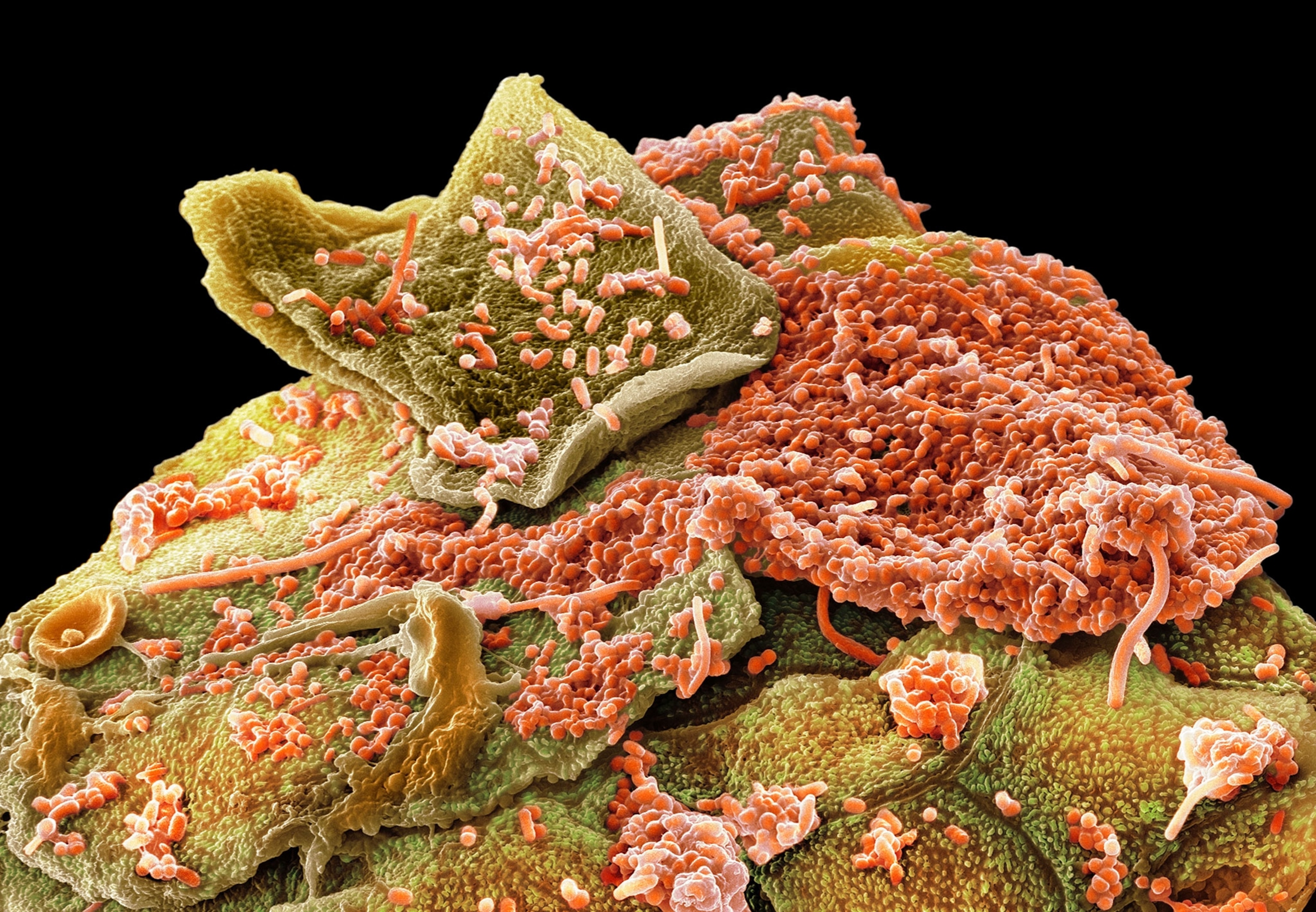

A microbial universe inside the mouth

The mouth hosts one of the body’s largest microbial communities. Known as the oral microbiome, it includes more than 700 species of bacteria, as well as fungi, viruses, and other microorganisms that occupy distinct niches throughout the mouth.

“The bacteria that live on your teeth are pretty much entirely different from the bacteria that live on your tongue,” says Jessica Mark Welch, a biologist at the ADA Forsyth Institute who specializes in the oral microbiome. “And there’s a different group of bacteria on the roof of your mouth and on your gums.”

In people with good oral health, the microbiome has a diverse community of beneficial microbes, including Streptococcus and Rothia, which help control inflammation and fend off pathogens. But that balance is sensitive. Changes in diet, oral hygiene, or overall health can quickly shift the microbial mix.

“Bacteria always respond to their environment,” Mark Welch explains. “If the mouth is exposed to a lot of sugar, then bacteria that thrive on simple sugars become more abundant.”

One of the best-known culprits is Porphyromonas gingivalis, a bacterium closely linked to periodontal, or gum, disease. While most bacteria prefer carbohydrates, P. gingivalis thrives on protein—quite literally feeding on gum tissue.

The recent JAMA Oncology study found that P. gingivalis and two other periodontal pathogens, E. nodatum and P. micra, as well as the common oral fungus Candida, were associated with a heightened risk of pancreatic cancer.

The mouth–body connection

Chronic inflammation is a well-established risk factor for cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes, several cancers, and Alzheimer’s disease.

People with periodontal disease are three to five times more likely to develop cancers linked to the oral microbiome. “The hypothesis is that they develop a pathogenic type of inflammation rather than a healthy one,” Freire says.

Blood vessels under the tongue, cheeks, and other oral sites allow bacteria to migrate through the body, Freire adds. The immune system typically intercepts these bacteria, but some slip through, potentially leading to disease.

Fusobacterium nucleatum, which is typically found in the mouth, is an example of a pathogen that can promote tumor growth through migration. Patients with colorectal cancer were five times more likely to carry F. nucleatum in their stool than healthy counterparts, according to research from the National Cancer Institute.

Saliva offers another pathway for bacteria to travel through the digestive tract. In animal studies, P. gingivalis that migrated from the mouth has been shown to cause pancreatic cancer, according to a 2024 study.

(Can gum infections trigger arthritis symptoms?)

Research has also linked gum disease to cardiovascular events such as heart attacks and stroke, likely through chronic inflammation and vascular damage. Oral pathogens may even affect the brain: studies suggest that gum disease can alter microglial cells, which generally help clear amyloid plaques—a hallmark of Alzheimer’s disease—though researchers caution that these connections are still being investigated.

The challenge of proving causation

Despite the growing body of evidence linking oral microbes to systemic disease, researchers caution that proving a direct cause-and-effect relationship remains difficult.

“You can ask people to consume different diets and measure what that does to their microbiomes, but there are experiments you can’t ethically do,” says Mark Welch, such as intentionally infecting people with pathogens.

Animal studies can help, but mouse and human microbiomes differ significantly. Moreover, humans host similar bacterial species in varying proportions, and those proportions fluctuate over time.

That’s why researchers are first mapping what a “healthy” oral microbiome looks like to identify when the balance tips toward disease, Mark Welch says. Genetics also plays a role: some people can have heavy dental plaque without gum inflammation, while others develop gingivitis easily.

The clinical frontier

Therapies targeting the oral microbiome are less developed than those for the gut or lungs, Freire says. Yet saliva, a window into systemic health, is emerging as a powerful diagnostic tool. It’s easier to collect than blood, and scientists are studying its composition for biomarkers that could signal disease.

(Why we add fluoride to water—and how it became so controversial.)

“If we can identify bacteria that serve as early indicators of cancers or other conditions detectable through saliva, we could diagnose them much earlier,” Mark Welch says.

Microbes themselves could one day become medicine. Some produce anti-inflammatory fatty acids, such as butyrate, which researchers are exploring for therapeutic potential, Freire says. Others may lead to new vaccines as scientists unravel how oral microbes interact with the immune system.

Freire and colleagues are also studying how oral bacteria influence neutrophils—white blood cells central to the immune response and associated with autoimmune disorders. They are also using artificial intelligence to map microbial persistence of pathogens such as SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, within oral tissues.

Keeping the oral microbiome in balance

The good news is that everyday habits can go a long way toward maintaining a healthy oral microbiome and, by extension, promoting overall well-being.

Eating whole, unprocessed foods rich in pre- and probiotics—such as fermented dairy, fruits, and vegetables—fosters beneficial microbes, Freire says. Omega-3 fatty acids, found in salmon, sardines, walnuts, flaxseed, and chia, also help control low-grade inflammation.

(Here’s how ultra-processed food harms the body and brain.)

Plant-derived nitrates from leafy greens, beets, and celery can also play a role. Bacteria such as Rothia reduce nitrate to nitrite, which the stomach then converts to nitric oxide, a compound that relaxes blood vessels and lowers blood pressure.

At the other end of the spectrum, sugar disrupts the microbial balance. Sweetened drinks, desserts, and even flavored yogurts feed harmful bacteria that promote inflammation and cravings. “From your mouth to your gut, it’s affecting how you crave food,” Freire warns.

The basics of good oral hygiene—regular brushing, flossing, gentle tongue scraping, and professional cleanings—remain essential. But scientists caution against using harsh bactericidal mouthwashes daily, which can wipe out helpful microbes along with harmful ones.

“You want oral rinses that freshen breath but don’t contain alcohol or detergents that disrupt the entire microbiome,” Freire advises. “Because there’s good in the microbiome as well.”