Can the City of Light Become the City of Beer?

I was in Paris last week—French agricultural structure is part of my ongoing research—and because it was late spring, I expected to see new fruits in the market and lighter cocktails in the cafés.

Here’s what I didn’t expect: To run into posters that proclaimed, in large and stylish letters, “

.”

Paris just isn’t much of a beer town. In any bistro or café, you’ll see the same brews from the same giant breweries: Amstel, Heineken, Kronenbourg, Pelforth. For a place so focused on eating and drinking with attention and precision—historically, and now freshly thanks to bloggers such as Clotilde Dusoulier and groups such as Le Fooding—France somehow missed out on the craft-brew revolution that bred a generation of beer geeks in England and the United States.

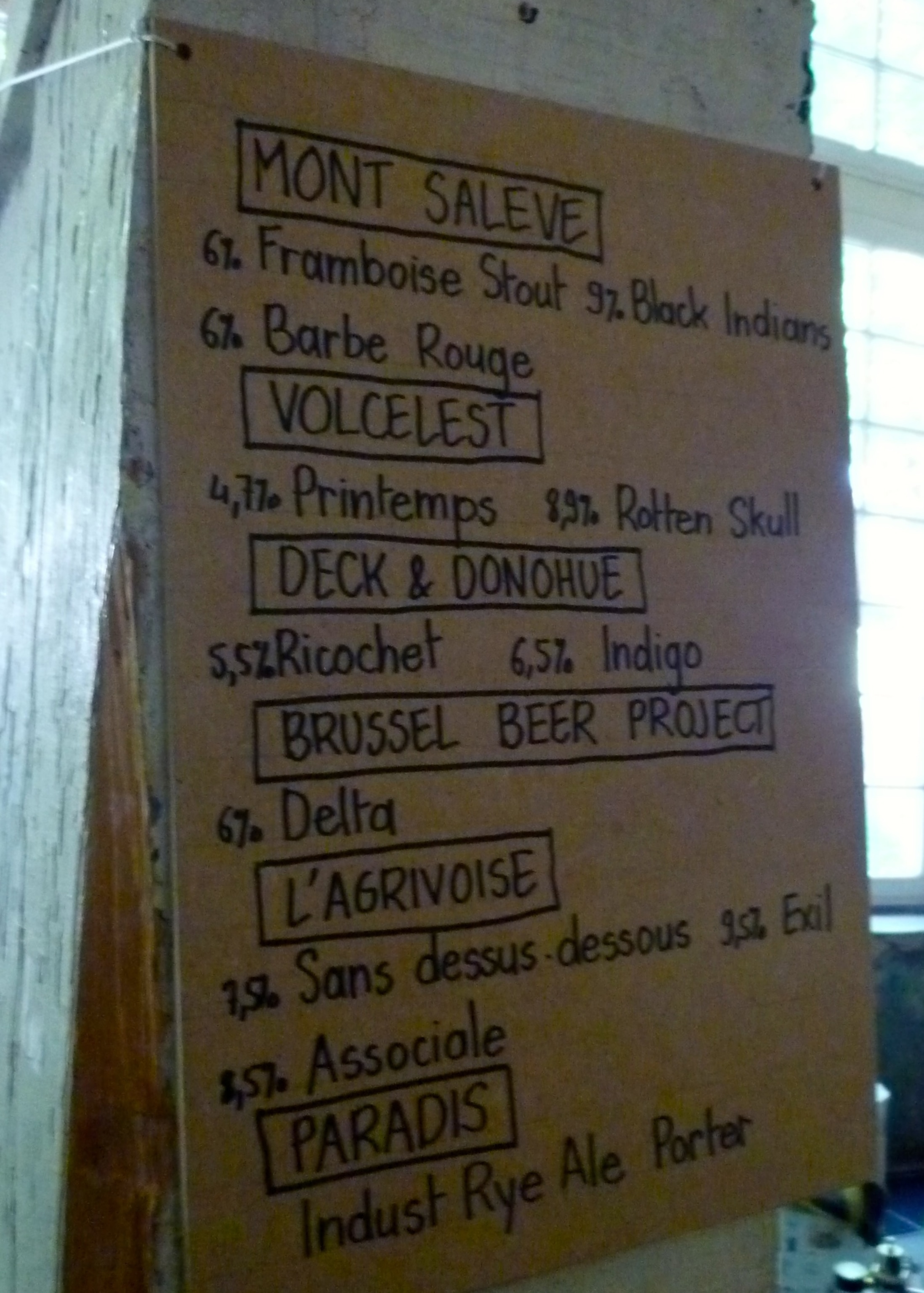

That seems to be changing. I spotted the poster in time to buy tickets to the week’s day-long closing party, held in a once-abandoned 17th-century convent that is still crumbling atmospherically, and discovered 30 brewers sharing types and styles of beers that would have been unthinkable 10 years ago. But as I heard from some of the brewers, and confirmed in quick visits to some new-style beer bars, craft beer in France is still a niche interest. It’s fighting to survive against industrial-scale breweries with a cheaper product and impenetrable distribution networks, the same struggle facing grass-fed beef, pasture-raised poultry, heirloom vegetables and almost-lost varieties of corn and wheat. But it is also facing off against a conservative food culture in which “values tradition” sometimes really means “dislikes change.”

In fact, whether craft beer succeeds in France could turn out to be a case study in how an artisanal product enters an established market, and in whether novelty and passion can overcome reliability and routine.

At the Beer Week party—the culmination of nine days of events—I met Anthony Baraff, an American software engineer brought to Paris by his wife’s job, who operates Les Brasseurs du Grand Paris with his friend Fabrice Le Goff. The partners met when Baraff bought home-brewing supplies from Le Goff, hoping to concoct his own solution to the paucity of complexly hopped American-style craft beers. They geeked out, compared recipes, and began brewing together in 2011 in a space above Le Goff’s walk-up apartment. Fairly soon, they realized there was a community of other brewers like themselves, all angling for an introduction to the Parisian palate.

“The market here is very bifurcated,” Baraff told me in a follow-up email. “There is a community of ex-pats, French who have lived abroad, and friends of the former two groups that make up a hardcore beer geek market. They expect beer to be extreme: bitter, strong, bold flavors and adventurous. Then there is a much larger market who only know beer as Heineken, Kronenbourg or one of the Belgian-branded abbey knock offs like Grimbergen or Affligem. They expect beer to be simply thirst-quenching, and have yet to experience what can be done with malt, hops, barley, yeast and other ingredients in the hands of someone who is willing to go beyond lager recipes or sugary Belgian styles. It’s often difficult to address these two parts of the market with the same beers.

Baraff and Le Goff now borrow space from other brewers to produce their beers, joining a cadre of other small-batch brewers determined to make a dent in the Paris market. They include Deck & Donohue, Outland, Zymotik, Distrikt and others—including Brasserie la Goutte d’Or, reputedly the first microbrewery founded within Paris. They are backed up by a raft of new-beer bars—La Fine Mousse, Les Trois 8, L’Express de Lyon and Supercoin—that serve as unofficial headquarters for the Paris craft-beer movement while also building up new audiences. Some of the brewers are finding shelf space in specialty beer stores such as Bières Cultes and Le Paris St. Bière; one, Parisis, sells its blonde and amber beers in my local supermarket.

The irony in this small explosion of craft-beer activity is that it is actually a renaissance. Paris once had a thriving micro-brew culture, housed in the brasseries that migrants from the province of Alsace brought to the city in the late 19th century. Brasseries were raucous and informal and open longer hours than traditional restaurants; they changed how Paris ate—but with their fresh, individual, northern-style beers, they changed how the city drank too.

Over the decades, the brasseries survived; when those of us outside France imagine a quintessential French restaurant, it’s often the dishes and furnishings of a brasserie that we see. But their beer culture was lost, preserved only in their name, which comes form the word for “brewery.” More than a century later, the new brewers of Paris may be bringing that culture back.

“it will be a long fight rather than an overnight change,” Baraff told me. “Already we’re getting somewhere though. I’d be more inclined to recommend Paris as a destination to have interesting beer, beer bars and breweries than I would for most towns in Germany. Next year’s Paris Beer Week will be many times larger than this year’s. There will be more craft beer bars, and more importantly we will continue to win over corner cafes and restaurants. It’s inconceivable to me that in 10 years that we will have the same situation, with bland industrial brew controlling every tap handle.”

This story is part of National Geographic’s special eight-month Future of Food series.