The disappearing art of making great Champagne by hand

To "riddle" a Champagne bottle is to turn it daily to remove sediment and make it crystal clear. And for the rarest bottles, only the human touch will do.

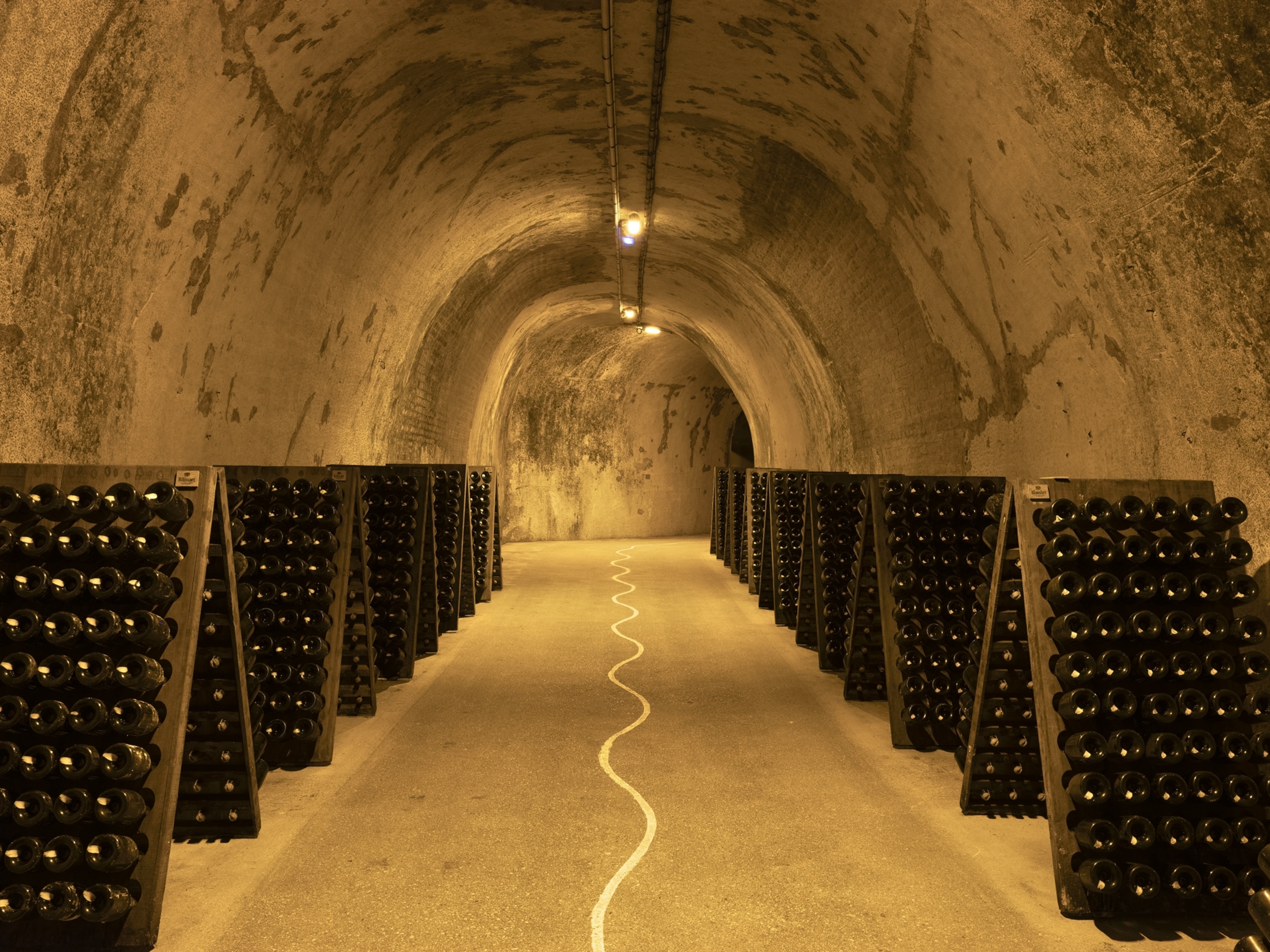

Pablo Lopez strikes a match and lights a short white candle as he peers inside a bottle of one of the world’s most coveted Champagnes. He is standing alongside a row of wooden A-frame racks filled with several other bottles in a damp, dark medieval cellar in Reims, France; the chalk-walled gallery belongs to Maison Ruinart, one of the oldest Champagne houses in the region. Today it’s also one of the few that still employ a traditional riddler—or remueur—like Lopez, who is tasked with filtering the sparkling wine by hand.

Lopez holds up a bottle so that the candlelight shines through the glass, showing sediment suspended in the liquid.

“You really need to understand the reading of the wines,” he says as he shakes the bottle to further loosen the dredge, an exercise called poignetage. It allows him to see the finer sediment, known as léger. It’s the léger he wants to control to ultimately remove it from the wine. This is the trickiest step, but also why he is so skilled in his craft. Without riddling, Champagne would be murky and cloudy instead of pristine and clear.

The process takes years to master, as it’s a complex and ever-changing study; Lopez has been a riddler for almost three decades and still doesn’t consider himself an expert. “My goal is always to achieve the best possible result,” he says. “If I’m not satisfied, I start over. We won’t move forward with a wine unless I consider it perfect.”

Combining both science and physical finesse in his practice, Lopez is among a dwindling breed of craftspeople who specialize in remuage in the Champagne region, about a 90-minute drive from Paris. Here, more than 131 square miles of vineyards—known as crus in the wine industry—are responsible for all the Champagne that consumers buy globally from store shelves and restaurant wine lists. (Famously, if it’s not produced here, it cannot be labeled Champagne.) In 2024, that totaled more than 270 million bottles, according to the region’s trade association, Comité Champagne.

It’s estimated that there are fewer than a dozen hand-riddlers still employed by a small number of the 370 registered Champagne houses—including at Ruinart, Maison Krug, Champagne Pol Roger, and Champagne Bollinger. For many brands, the task of rotating bottles has been outsourced to automated machines called gyro-palettes, which often work faster and, at times, more efficiently. Even houses with hand-riddlers, like Krug and Ruinart, now use gyro-palettes to turn a majority of their bottles in order to ramp up production; in many cases, the riddlers filter only the most expensive and rarefied cuvées by hand.

While technology has played a major role in the ability to produce enough Champagne to meet consumer demand, that transition comes at the expense of artisanal heritage, and that’s what some producers say is alarming: the loss of knowledge for a critical step in what makes Champagne Champagne. Though the gyro-palettes have generally been embraced, these houses are determined to keep the art of hand-riddling alive. As a keeper of this traditional yet fleeting wisdom, Lopez hopes the expertise will continue to be cherished by the next generation. “Passing on the knowledge is essential,” Lopez says. “The traditional craft itself could vanish if we do not preserve it.”

During the remuage, Lopez will visit the cellar daily to carefully rotate bottles a quarter, an eighth, even a 16th turn at a time, to the right or the left. The riddling is done in three cycles, starting with one turn a day before working up to two and ultimately three turns daily as the sediment collects. He’ll mark the bottles with chalk, noting sediment placement and tracking his movements. Most notably, he’ll “feel” the wine as he goes—the part of his job that comes from sheer experience, repetition, and intuition.

“Every wine is different, and every year the harvest changes, so we must start over each time,” Lopez says. “The wine truly guides us.”

Mastering the craft

Riddling is an integral part of the production of Champagne, which is different from other wines in that it always undergoes two fermentations to create those quintessential celebratory bubbles.

After the grapes—Chardonnay, Pinot Noir, Pinot Meunier, or a blend—are harvested from the vineyards, they are pressed into juice and fermented in stainless steel vats or wooden barrels, forming what winemakers refer to as a base wine. Any given harvest can produce dozens of base wines, which are blended into cuvées, then bottled under various terminologies like prestige cuvée or noted with a specific vintage date. Maison Krug, for example, includes up to 180 different wines in its numbered editions of Krug Grande Cuvée.

Once the cuvée is bottled, the chef de cave, or winemaker, will add a mixture of wine, yeast, and sugar to kick-start a secondary fermentation in each bottle. That’s what creates the iconic bubbles but also demands the work of the riddler.

During the secondary fermentation, the Champagne accumulates dead yeast cells called lees, crystallized particles called tartrates, and other floating gunk. Meanwhile, the riddler jumps into action, manually twisting the bottles as they rest on pupitres, or wooden racks, with their necks pointed toward the floor at a 45-degree angle.

To “read the wine,” riddlers like Lopez assess the amount of sediment in a bottle and slowly manipulate the angle, axis, and rotation over the course of six to seven weeks in order to guide the léger toward the neck. Then the sediment is frozen solid and the temporary cap on the wine bottle is removed. The pressure from the bottle—the same type of pressure that causes Champagne to pop when you open it—forces out the icy sludge. The chef de cave adds a mix of sugar and extra wine to top off the liquid in the bottle before sealing it back up with an iconic mushroom-shaped cork.

But the act of remuage is not the same for every bottle. “The gesture of riddling needs to be adapted from one wine to another,” says Florent Michel, the remueur at Champagne Bollinger in Aÿ. “The gesture is simple, but it takes time to understand the movement of the lees and manage it to have a nice deposit in the neck of the bottle.”

Michel would know. He is responsible for hand-riddling all of Champagne Bollinger’s prestige cuvées and vintage Champagnes, including La Grande Année, La Grande Année Rosé, R.D., and Vieilles Vignes Françaises—which can sell for up to thousands of dollars per bottle—as well as all the large-format bottles, like magnums and jeroboams. It’s been his main role at the family-run house for more than 30 years.

Michel was first introduced to riddling in 1990 by Patrice Charon, then the riddling manager at Bollinger. He was hooked immediately. Though he had already worked at the house for eight years, it was riddling that really inspired his career trajectory.

“I knew I wanted to master the craft as my top focus,” he says.

It took about two years of apprenticeship with Charon for Michel to get the basics down, but, as riddlers in Champagne say, you never really master the art; the gestures change with every blend and every vintage. You must approach each wine as if it’s unlike any you have ever riddled before, and you must continue to be intentional with every movement. The skill is one that requires extreme focus.

Raphael Joyon, the remueur at Maison Krug, has also been riddling since the 1990s. Like Michel, Joyon studied under a mentor whom he credits with teaching him not only the technique but also how each wine’s unique structure informs the manipulation. There is no recipe or rigid process to follow—and you can’t learn any of it in a book.

For Joyon, the nuance—and challenge—of every new wine that passes through his hands is what has been a driving force in his passion for riddling. Maison Krug is known for its precision in winemaking and high-end cuvées, such as the Krug Rosé, which blends together some 150 different wines. And for Joyon, no two riddling sessions will ever be the same.

Sometimes the sediment is volatile, Joyon says, while other times it’s compact. He notes that rosé tannins can be particularly tricky and often require extra care. The act of riddling is about picking up on these subtle cues.

“You have to understand [a wine’s] rhythm, its personality, and how it responds to each gentle movement,” Joyon says.

But riddlers must also move quickly. Olivier Krug, the sixth-generation director of Maison Krug, notes that riddlers can turn some 50,000 bottles a day by hand. Each bottle takes only a fraction of a second to turn, and Joyon likes to listen to classical music while turning them. He can finish a row of pupitres in minutes.

Krug finds it meditative to watch.

“There is an energy to riddling,” Krug says. “A riddler’s fingers have to feel the wine, and riddlers have to preserve that energy in their hands.”

Rise of the machines

Riddling was first introduced to Champagne winemaking in 1881 at Veuve Clicquot. The house credits Barbe Nicole Ponsardin Clicquot, “Madame Veuve Clicquot,” with the invention of the methodology alongside her then cellar master Antoine de Muller. The pair experimented with ways to clarify their sparkling wines, leading to the codification of riddling as well as the invention of the pupitres, which allow riddlers to more easily turn the bottles as they slowly invert them. Today it would be a feat to find a house that doesn’t riddle its wines either by hand or with a machine.

For all the romance of hand-riddling, though, the vast majority of Champagne producers have transitioned to using gyro-palettes, the cubically shaped machines that automate the process. Around the turn of the 21st century, these machines hit the market and quickly caught on in the Champagne region.

Not only are the gyro-palettes faster and cheaper, but some Champagne producers argue they are more precise. For a business with very slim profit margins, according to Peter Liem, a James Beard Award-winning wine critic and author of Champagne: The Essential Guide to the Wines, Producers, and Terroirs of the Iconic Region—when a year of bad weather can wipe out a significant chunk of the agricultural crop—the technology has been almost impossible to ignore.

At Champagne Laurent-Perrier in Tours-sur-Marne, enologist Constance Delaire says the house is no longer investing in hand-riddling for popular bottles like La Cuvée Champagne. The process was extremely tough, physical work that resulted in shoulder, back, and wrist problems for the riddlers, she says. The team now automates riddling with the gyro-palettes for production, with the rare exception of very specific cuvées like Grand Siècle Les Réserves, which is produced only after exceptional harvests, typically every few years.

Two cellar workers at Laurent-Perrier have mastered the craft of hand-riddling, Delaire says, but she doesn’t expect them to do the work of riddling 60,000 bottles a day. She explains that there is a difference between nodding to the ancestral craft and doing the labor day after day, especially when it comes with downsides. It would simply take too much of a toll on the human body when there is a viable and clear alternative, she says.

“It’s a deliberate choice, driven by concern for our workers’ well-being,” says Delaire. “That’s what proper modernity means to us: honoring our heritage by passing on knowledge and focusing human craftsmanship where it creates exceptional value.”

More and more, the big Champagne houses have adopted the palette-first mentality. “Almost everyone can agree there is no qualitative difference between hand-riddling and gyro-palettes,” explains Liem. “There is no controversy about them, no anti-gyro-palette movement. But the Champenois are really proud of their history, and since riddling is so uniquely Champagne, it has survived.”

A typical winemaking model, Liem explains, is to use a gyro-palette for nonvintage house cuvées and to focus on hand-riddling select prestige cuvées and vintage cuvées, which may amount to only 3 percent of a brand’s total production. For houses like Champagne Bollinger, which makes several specialty blends, the prestige bottles are a larger segment of their production, and therefore the brands put more emphasis on the traditional craft involved, especially in their marketing.

Despite how important riddling is to the production process, it’s not well understood by the average wine consumer—but that doesn’t stop Champagne houses from talking about riddling by hand. Walk into any Champagne tasting and the sommelier will note how the wine is riddled. Specification sheets about a particular bottle of Champagne, given to wine shops and restaurant beverage directors, will often list hand-riddling. And the wine production notes for consumers, sometimes found on a QR code on the bottle, also list this step in the process.

“As consumers, we like handmade things,” Liem says. “We like artisanal products because we believe that contributes to the final product. Even if it doesn’t qualitatively, tradition is not nothing.”

The future of riddling

Dominique Demarville, the chef de cave of Champagne Lallier in Aÿ, teaches every new hire how to hand-riddle, even though the house uses gyro-palettes for all its Champagnes except the large-format bottles (which do not fit in a gyro-palette). He believes that anyone working in the cellar must understand the manual process to better work with the mechanical one. Plus, he says, the reading of the sediment must still be done in person, using the human eye.

Demarville has taken it upon himself to be a leader in the preservation of Champagne’s traditional crafts. He observes that the younger generation’s cellar workers have less knowledge of historical Champagne production, even if they do have an interest in learning about it. Indeed, the hand-riddling process often fascinates the newer cellar workers; it’s more instinctual than they might guess, and they really have to let go of overthinking it when they try it themselves.

“The craft is important because it is in the DNA of the winemaking,” Demarville says. “We want them to keep this knowledge, because there is always a need for the human touch.”

Whether a house has a formal program for apprenticeship or simply teaches winemakers and cellar workers how to riddle on the side, there is an emphasis by producers to maintain the knowledge of riddling. Liem explains that many smaller producers, often referred to in the industry as grower Champagnes, still riddle by hand since they may not make enough wine to warrant the purchase of a gyro-palette. Others, like Jacques Selosse, do it by choice, since the house philosophy is rooted in these ancestral techniques. And larger houses, some with backing from luxury conglomerates, have the capital to employ riddlers and take the time to mentor the younger generation.

When asked about the future of hand-riddling, Michel from Champagne Bollinger is unfazed. He is currently training colleagues himself, in the same way he learned from Charon years ago.

“The only way to learn the correct technique for placing the sediment in the neck of the bottle is through repeated practice with several vintages and cuvées,” Michel says. “It cannot be taught in a classroom.”

For training, he starts one year before the riddling process on a particular cuvée will begin. This is when he and his trainees test a few bottles to determine their strategy and optimal cycle for that specific cuvée. To showcase how sediment moves, Michel uses chalk marks on the bottles to record the concentrations and track the progress.

One colleague, Olivier Lannez, has been learning from Michel for years and is poised to take over the role when Michel retires. When Lannez is asked why he wants to become a remueur for Bollinger, he responds as riddlers typically do: to protect the craft and pass along the knowledge so that it is not lost forever.

Plus, Michel adds, riddling is a role that’s crucial to the quality of the final product, where you work with the house’s most prestigious vintages. He is immensely proud of his role as a member of the team, as well as every corked cuvée that passes through the hands of a Bollinger riddler.

“This commitment to craftsmanship and preservation of a labor-intensive technique underscores Bollinger’s philosophy that, if it’s good for the wine, we do it,” Michel says.

“There is something very special knowing that I am helping to preserve an almost forgotten, artisanal practice,” he adds, “that remains an essential pillar for Champagne.”