Bidibidi, Uganda — On the morning of July 17, 2018, Hadia Michael woke up with a fever. She asked her daughter to skip school to help her watch the other kids. She’d been staying with her cousin, Ronah Halima, since a month before, when her husband had come home drunk and they’d fought. He hit her and ripped off her extension braids, pulling out the real hair underneath, too.

Hadia and Ronah lived just a few yards apart, their small clusters of mud-and-thatch houses nearly touching behind a row of market stalls in Bidibidi refugee camp in Uganda. The camp, the second largest in the world, had sprung up in the summer of 2016 as tens of thousands of refugees fled the civil war in South Sudan. Ronah and Hadia had been among the first to arrive, and were given prime plots next to where humanitarian organizations set up shop. Nearly three years later, a quarter-million people are still stuck in Uganda, awaiting for their leaders at home to strike a long-promised peace deal. In cemeteries across the sprawling camp, some will stay forever.

Hadia was unconscious by the time Ronah got home that day. They took her to a clinic and hooked her up to an IV. She died almost as soon as it drained. It was midnight. She was 26 years old. An ambulance took her body to the nearest city. Some people speculated that she’d taken drugs to induce an abortion, but the doctors who inspected her reported no evidence or cause of death.

Death is like that in Bidibidi. A refugee camp is built to be temporary, but within it there are shades of permanence that could someday outlast its inhabitants: a brick-and-mortar clinic, a water piping system, a final resting place. But health care is still scattered and ill-equipped, so the end is often a mystery. Some clinics are just white tarps hanging shabbily from wooden beams, and private pharmacies in the markets offer more painkillers than medicine. For refugees there are two options when their loved ones die: bury them in the camp, where they may someday be left, or take them on a dangerous journey home to South Sudan.

Ronah didn’t care where Hadia was buried; she was already dead. But Hadia’s family cared. “I took her to South Sudan because they want the children to know this is grave of their mother,” says Ronah, a few months later, sitting in the shade outside her home. “If she’s buried here and people go back [to South Sudan] then they will never be able to see their mother’s grave.”

The agency overseeing the camp does not help transport bodies, so Ronah hired a seven-seat mini bus at the market. At 5 a.m., they left for the border of South Sudan. Eight adults and Hadia’s three children squeezed in, some sitting on the coffin. It took seven hours to reach the border.

They slept before crossing and the next morning made the four-hour trip to Juba, the capital. The war in South Sudan, where government factions had divided the country along ethnic lines, was still raging. The drive was risky. The year before there were rumors that soldiers burned a funeral convoy killing everyone inside.

In Juba, Ronah learned their car had narrowly escaped a similar fate: the vehicle behind them had been ambushed. Ronah transferred the body and the death certificate to Hadia’s mother-in-law, and dropped off Hadia’s kids with their aunt and uncle. A second group took the body more than 100 miles farther, to a small village called Karika, where her parents still lived. She was buried in her family’s cemetery.

The trip cost nearly $400, paid for by a relative of Hadia’s now living in Australia. With such a high price tag attached to a home burial, cemeteries in Bidibidi are filling up.

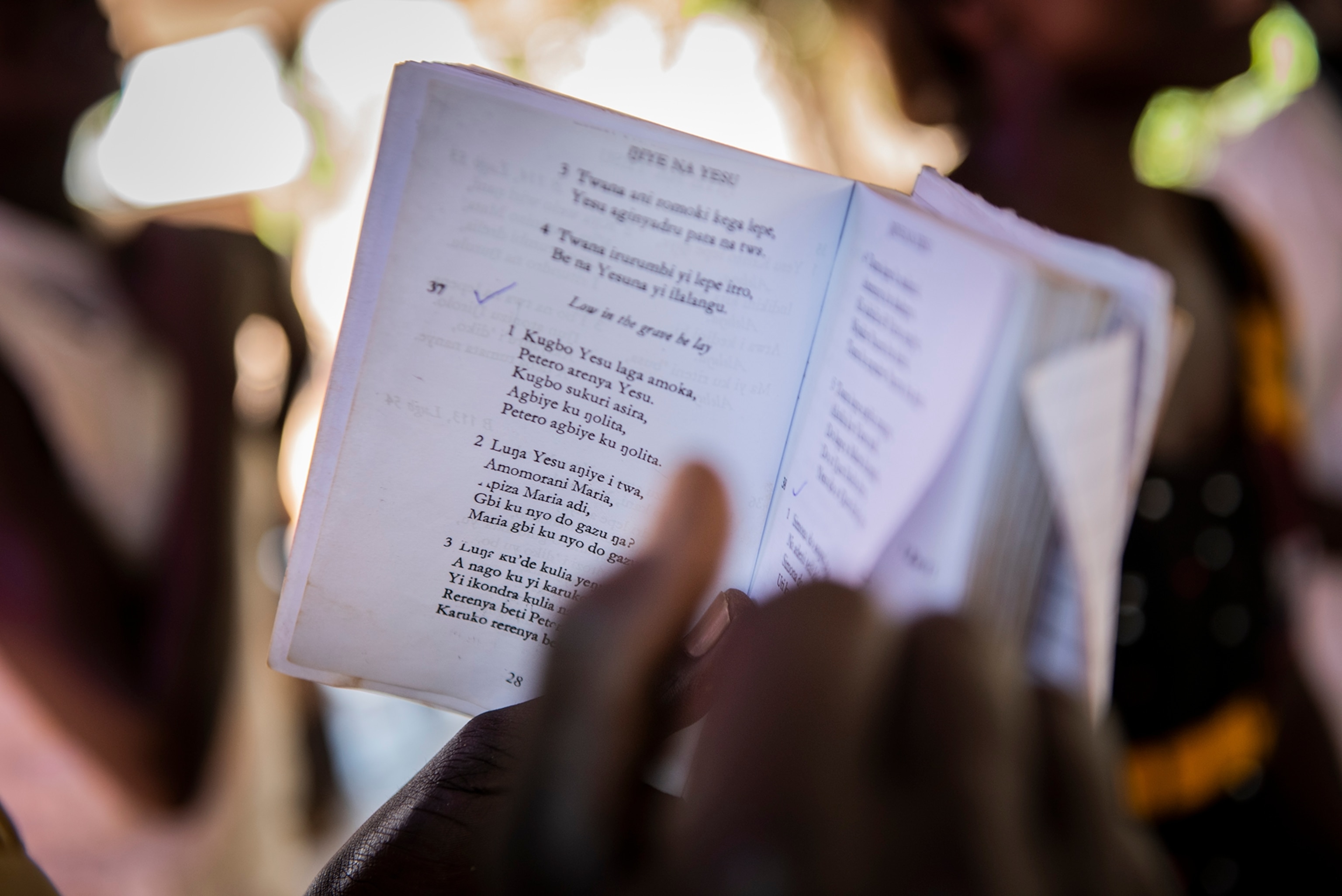

When someone dies there is a chain of events that must happen: the village chairperson must be contacted. He or she must contact one of multiple international NGOs that coordinate burials. A coffin must be purchased from a market outside the camp. A priest will be enlisted to run the service. Food for hundreds has to be purchased and cooked. Hopefully a truck will arrive to bring the body to the cemetery, where local men will have spent the morning digging a grave.

The first cemetery in the section of Bidibidi where Hadia lived sits at the intersection of two roads. When the camp opened in 2016, as the refugees poured over the border, there were many burials. Now, there are a couple a month. The Catholic church oversees the site, but the families dig the graves themselves and make the markers. Some graves are covered in tattered clothing. In South Sudanese tradition, only the uncles can take the clothes of the dead and if the uncles decline to, they are laid out on the grave. Some have sheets draped over the concrete blocks. Others are just piles of stones.

But that cemetery had recently gotten too full, so a second cemetery opened in the area. On a warm day in the fall, a body is about to be buried there. As the news spreads through the massive camp that Lily Ipayi, a refugee, mother, and tailor, has died after a decade-long fight with HIV/AIDS, new arrivals enter the small village where she lived. At the end of a dirt path leading off the main road, more than a hundred people have gathered in plastic chairs under a tarp strung over tree limbs for the funeral. A crying woman in a red dress kneels beside a wooden bed. Laid along the middle is a small woman wrapped in an embroidered white sheet. More decorative sheets are hanging behind her and the air is filled with chanting and drumming.

When a new mourner arrives, the music slows and a prayer or memory of the dead is announced. Some leave to wail outside the covering, sing, or stand up to dance. “God, guide us, the people from South Sudan, give us courage, you are the only one who strengthened us,” one man preaches. Various visitors stand up to deliver sermons. An impassioned priest screams about the fires of hell. “We are running here because of death,” he shouts. The violence in South Sudan has displaced more than two million people. “But death is taking us one by one.”

As they wait for a coffin to come from a nearby town, giant pots of beans and greens boil nearby. A pot is passed around for contributions, and small bills are deposited to help the family pay for the funeral costs.

Lily’s husband, Desmond Dongo, sits outside in a crisp blue button-down. Before she died, he spent months shuttling her back and forth for treatment outside of the camp. In the end, she needed a blood transfusion. They tried every hospital, but none had it. They decided to just come home to Bidibidi, where she died the next day. She was 42 or 43 years old, he says.

After, he went to the market to ask how much it would cost to take her body to Mongo, the village where he’s from in South Sudan. The quote was $250. He decided to keep her in Bidibidi now and move her home later, once it’s safe and he’s made enough money. “It’s better to bury her here and take to her to South Sudan in the future,” he says.

The next morning at 9 a.m., the coffin arrives, covered in purple cloth. “We don’t know if we’ll die here or in South Sudan,” the officiating pastor says. After he speaks, men hammer 13 nails into the coffin and place it on the bed, draping an embroidered sheet over it. These sheets, Lily’s husband says later, were made by her. They helped her earn enough to send her child, their three foster children, and his second wife’s children to school.

Later, the coffin is loaded into a pickup truck and driven down a bumpy road surrounded with head-high grasses. Men run ahead of the car, piling rocks in holes so the ride is as smooth as possible. In a small clearing, Lily is laid to rest alongside others who died in Bidibidi. Someone points out a nearby grave of a young man whose motorcycle crashed en route to get his monthly rations from the food distribution center. As the coffin is lowered, the priests sing and someone drums a hypnotic beat. Dirt is pushed into the grave and pounded down with sticks. Those crying remove themselves from the circle, their staccato wails fill the small cemetery like a bird song.

The funeral, Desmond says, will go on for months, with people arriving from far-flung camps to pay their respects. Then he recalls that when she first got sick in May, she asked whether he’d take her to South Sudan if she died. They were in an ambulance to the hospital. “I told her I could not bring her to South Sudan because security isn’t good,” he says. “I told her I would bury her here.” She didn’t react and they didn’t talk about it again.