How did the walls of ancient Jericho fall? Archaeology offers a clue.

Centuries of excavations have unearthed a few theories about what really brought down one of the oldest cities in the ancient world.

.jpg)

The fall of Jericho is one of the most popular stories in the Bible. According to the Old Testament, Israelites—a group of Hebrew people whom Moses had led out of Egypt—conquered the city of Jericho in dramatic fashion: At the direction of God, they surrounded the city, blew on horns, and, with a little divine help, the blast was so powerful that it knocked over the city’s heavy walls. The story showcased the might of God and argued that the Israelites were his chosen people.

Jericho wasn’t just a biblical city. Modern Jericho still exists in Palestine’s West Bank and is popularly considered one of the world's oldest cities. The ruins of Jericho’s ancient remains are located just outside the sprawling modern city center. These ancient remains are now the UNESCO World Heritage site Tell es-Sultan.

Archaeologists have been excavating Tell es-Sultan for over a century, learning just how deep Jericho’s roots stretch. Here’s what they’ve discovered about the destruction of one of the oldest cities in the world—and the accuracy of the biblical story.

Jericho’s roots go back millennia

Humans have been living at Jericho for 10,000 years. Nestled in the Jordan Valley, the site sits west of the Jordan River. Its early settlers were part of an agricultural revolution in the so-called Fertile Crescent, transitioning from being hunter-gatherers to farmers in permanent settlements.

Jericho had a series of walls—perhaps to protect the city—and a stone tower whose function remains a mystery. In the Neolithic and Early Bronze Ages, Jericho underwent periods of destruction and abandonment, but archaeological finds show it always seems to have been rebuilt. Archaeologists have been able to determine this based on their dating of Jericho’s walls—newer walls were erected years after older ones had been destroyed.

(What was the Neolithic Revolution?)

The city of Jericho reached its height in the Middle Bronze Age, which lasted from roughly 2000 to 1500 B.C. Jericho was part of the Canaanite civilization, a cultural group that lived in the region known as Canaan in the Levant. According to archaeologist Felicity Cobbing, chief executive and curator of the Palestine Exploration Fund, “It’s a trading civilization. It has very, very good links with Egypt and the Mediterranean world as a whole. It’s a comfortable, successful place.”

Sometime toward the end of the Middle Bronze Age, Jericho experienced a major calamity: The ancient city was destroyed. No one knows exactly what happened, but the event pushed Jericho into a period of less significance.

What the Bible says about Jericho’s destruction

The Bible offers one explanation. After Moses’ death, Joshua became his successor as leader of the Israelites.

Under Joshua’s leadership, the Israelites invaded the region of Canaan, which God had gifted to them in exchange for their commitment to him and his word. He also commanded Joshua and the Israelites to “drive out from before you the Canaanites.”

As recounted in the Book of Joshua, the Israelites targeted and circled the walled Canaanite city of Jericho for six days. On the seventh, they sounded ram’s horns, shouted, and, by a divine miracle, Jericho’s walls tumbled down. The Israelites then sacked the city, burned it, and “devoted to destruction by the edge of the sword all in the city, both men and women, young and old, oxen, sheep, and donkeys.”

Scholars date the rise of Israelite presence in Canaan to sometime around 1200 B.C. To validate the biblical story, modern archaeologists would need to prove that Jericho’s walls fell down around the same time.

What archaeologists have learned about the ancient city

Since the 19th century, Tell es-Sultan has been identified as the site of ancient Jericho. Scholars came to this conclusion based on its location in the Jordan Valley and the presence of a natural spring, which the Bible claimed was near the city.

The first major excavation of Tell es-Sultan was led by Ernst Sellin and Carl Watzinger concluded in 1911. It revealed that Jericho had likely been destroyed. They also found evidence of city walls at the archaeological site.

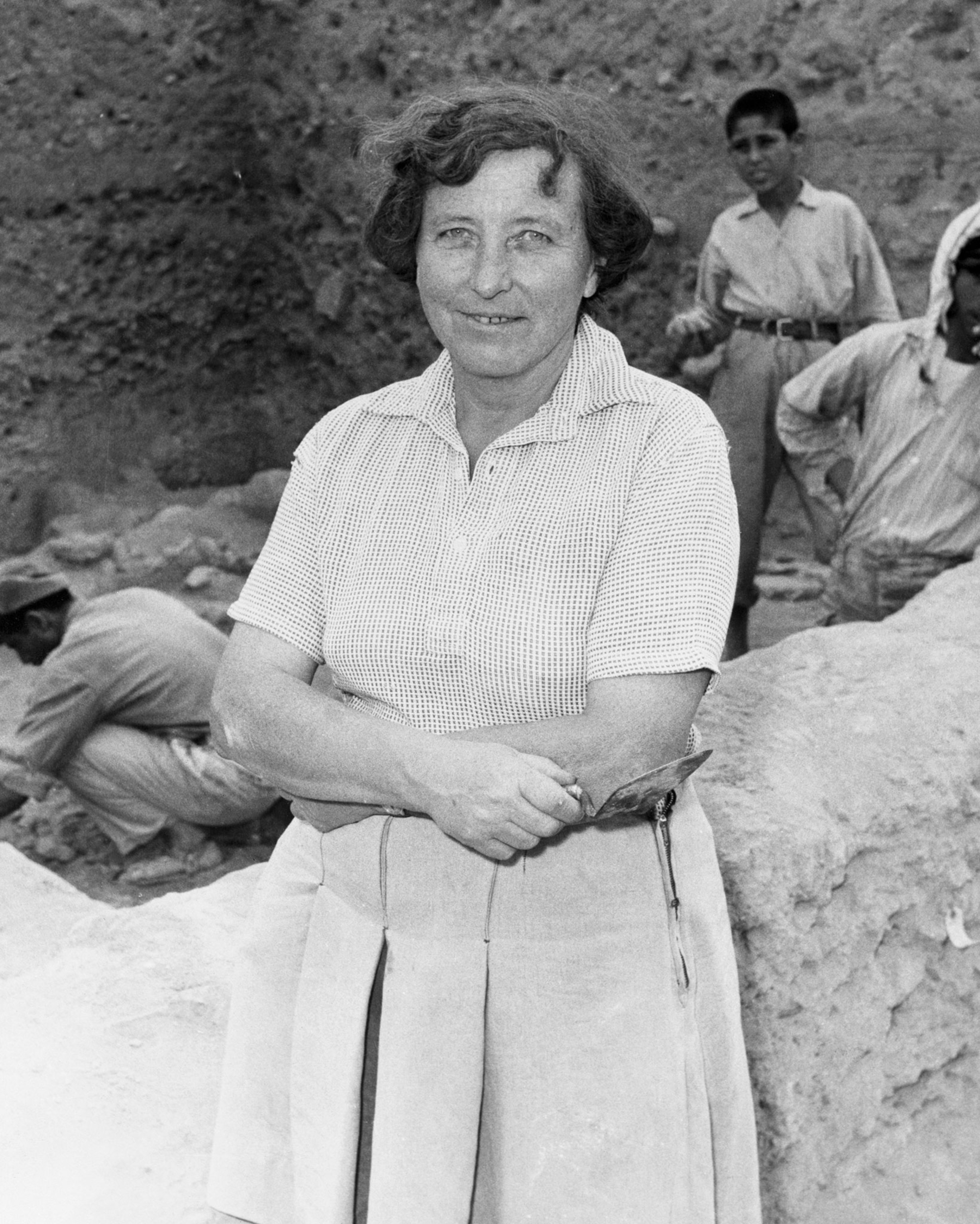

During British archaeologist John Garstang’s excavations in the 1930s, he argued that the site fit the biblical story and dated a set of walls to roughly 1400 B.C. However, new evidence soon emerged suggesting otherwise. One of the most influential archaeologists of the 20th century, Kathleen Kenyon, conducted an extensive excavation of the site from 1952 to 1958. Analyzing the site’s stratigraphy—layers of archaeological remains—and pottery shards, Kenyon established that the walls Garstang analyzed actually dated to 2700 B.C., well before the rise of the Israelites.

(Was the Garden of Eden a real place?)

“Jericho has had many walls,” says Cobbing. “None of them, however, fit with the story of Joshua’s conquest."

That’s because Jericho didn’t have any walls for the Israelites to knock down. Kenyon’s discoveries suggested that Middle Bronze Age Jericho was destroyed sometime around 1550 B.C., a finding that was later confirmed by radiocarbon dating conducted in the 1990s. The Israelites, on the other hand, supposedly conquered the city hundreds of years later.

But the date of Jericho’s destruction wasn’t the only thing Kenyon’s excavations confirmed. She found that a great fire had consumed the city at the time of its destruction in 1550 B.C.—but what had caused it?

The leading theories on what really fueled Jericho’s fall

Scholars say Jericho sits in an earthquake zone and earthquakes seem to have damaged the ancient city’s walls and buildings at different points in its history, especially in the Early Bronze Age.

Earthquakes have a specific signature, Cobbing explains. “You have a wall trotting along quite nicely, and then suddenly it slips, and it’s 50 centimeters lower,” she says. “Likewise with the corresponding floor level. Or you get buckling.”

Archaeologist Lorenzo Nigro, who has led recent excavations of Tell es-Sultan, concluded that “a violent earthquake struck” around 2700 B.C., requiring the city to be “completely rebuilt.” He has also argued that Jericho’s residents adapted their building techniques over time to mitigate the effects of earthquakes.

Garstang, for one, concluded an earthquake had destroyed Jericho. He reconciled this with the biblical version of the story by suggesting that Israelites then set fire to the devastated city, since Jericho’s remains reveal a layer of ash, suggesting a major fire.

Other researchers point out that fires frequently follow earthquakes, even today. All it would take is one oil lamp to get knocked off a shelf and into an open fire to start a conflagration that could soon engulf the whole city.

When it comes to the structures that existed around the time of Jericho’s destruction around the year 1550 B.C., they are intact, “just burned to a crisp,” Cobbing explains. She adds that archaeologists have even found jars filled with burnt grain.

The burnt remains of Jericho might suggest warfare, she adds, but likely not from Israelites—perhaps from Egypt, a theory that Kenyon also suggested. In the 16th century B.C., Egypt was in the midst of a campaign expelling Hyksos, a group of people who briefly ruled Egypt. The ancient group was chased into Canaan, fitting with the timeline of Jericho’s destruction.

Cobbing says the siege would have been “massive.”

“It wasn’t just a raiding party. This was the full force of the Egyptian army laying waste to Jericho,” she explains.

However, there isn’t much archaeological evidence—such as arrowheads or mass graves—to support the siege theory. “I wonder whether the inhabitants didn’t have a bit of forewarning,” Cobbing theorizes, suggesting that Jericho’s civilians could have fled ahead of the attack.

No matter how Jericho was destroyed, the result was the same. The city was largely abandoned and unfortified—for a little while at least. Jericho was revived in the Iron Age, and in the 9th century B.C. had a wall once more. In the subsequent centuries, it would endure—even hosting Herod the Great in the first century B.C.

“I think that’s the remarkable story of Jericho,” says Cobbing. “It’s about resilience. Never mind it being hard, never mind it being sometimes cataclysmic—it’s a place people come back to again and again.”