Mapping the Urban Bike Utopias of the 1890s

Bicycle mania swept the nation at the end of the 19th century. Can it happen again?

When you live in San Francisco, it’s not uncommon to see strange sights out your window. Once, I saw the mayor standing in the middle of the street, painting a bright green square on the asphalt.

This was a historic moment, I later learned—the inauguration of the city’s first “bike box,” a designated space for cyclists to wait at an intersection. That was in 2009. Cycling continued to grow in the following years. By 2015, San Franciscans took an estimated 82,000 bike trips per day, and the total length of the city’s bike lanes was 125 miles and growing.

The popularity of cycling in cities around the country, advocates say, is an encouraging trend that reduces traffic congestion and air pollution and promotes healthful exercise. But it’s not exactly new.

The maps in this post come from an earlier time when cycling mania swept the nation: the 1890s. The bicycle as we know it—with two wheels of equal size, among other features—had just been invented. “Bikes really took off in cities because they provided the first affordable private transportation,” says Evan Friss, an urban historian at James Madison University. “Horses were expensive, and cars, by and large, didn’t exist yet.”

In his 2016 book, The Cycling City, Friss writes that the bicycle gave middle-class people more freedom to travel when and where they wanted. It allowed them to get around the city more efficiently, but perhaps more importantly in an era of rapid industrialization and urban population growth, it allowed them to escape it.

“There was this great notion that on a bicycle you didn’t need a plan,” Friss says. “You could start out in the city and end up at the beach or a mountain or just go see some foliage.”

Then as now, bicycle advocates pushed for road improvements, and for dedicated lanes and paths for bike traffic. Local cycling clubs sprang up around the country (Manhattan alone had more than 50), and in 1897, the League of American Wheelmen boasted more than 100,000 members.

The most significant early bike path in the country was the Coney Island Cycle Path, which ran five and a half miles from Prospect Park in Brooklyn to Coney Island (it’s shown in the map at the top of this post). Completed in 1895, it epitomized the intent of many bike paths of the era—to give urbanites an easy way to get out of the city for the day.

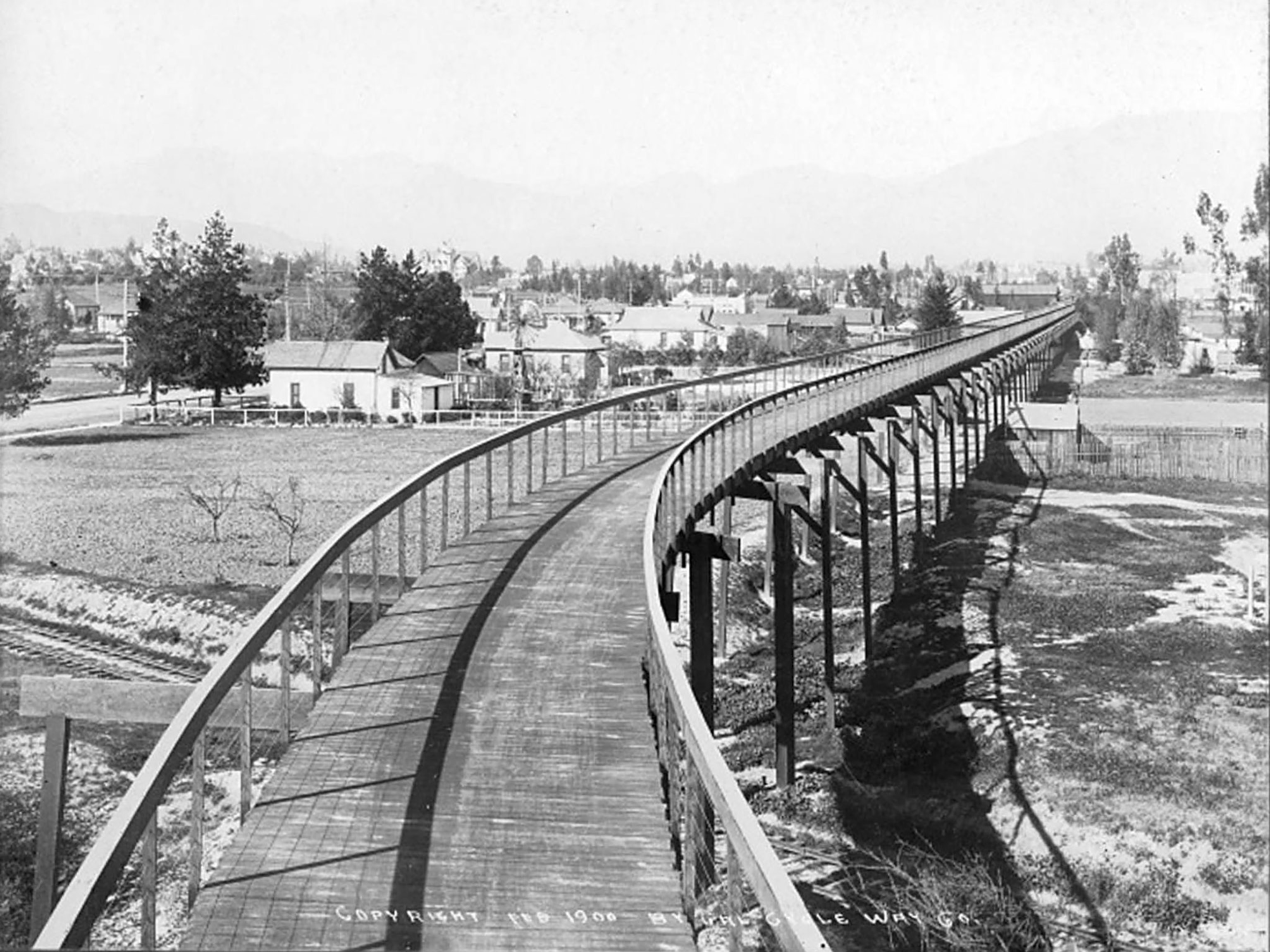

Even grander plans were proposed, including an illuminated “aerial bicycle highway” in Chicago; a 40-mile toll route connecting Baltimore and Washington, D.C.; and even a transcontinental route between San Francisco and New York. None of these came to pass. Construction did begin on a proposed nine-mile elevated bikeway between Los Angeles and Pasadena (see photo below), but the project was never completed.

The dream of the 1890s is alive in Portland, my current home town. The Oregon city routinely ranks near the top on lists of the most bikeable cities. Last year it opened a new bike-friendly bridge across the Willamette River, debuted a $10 million bike-share program, and approved a gas tax that will provide $28 million over four years for safety improvements for cyclists and pedestrians.

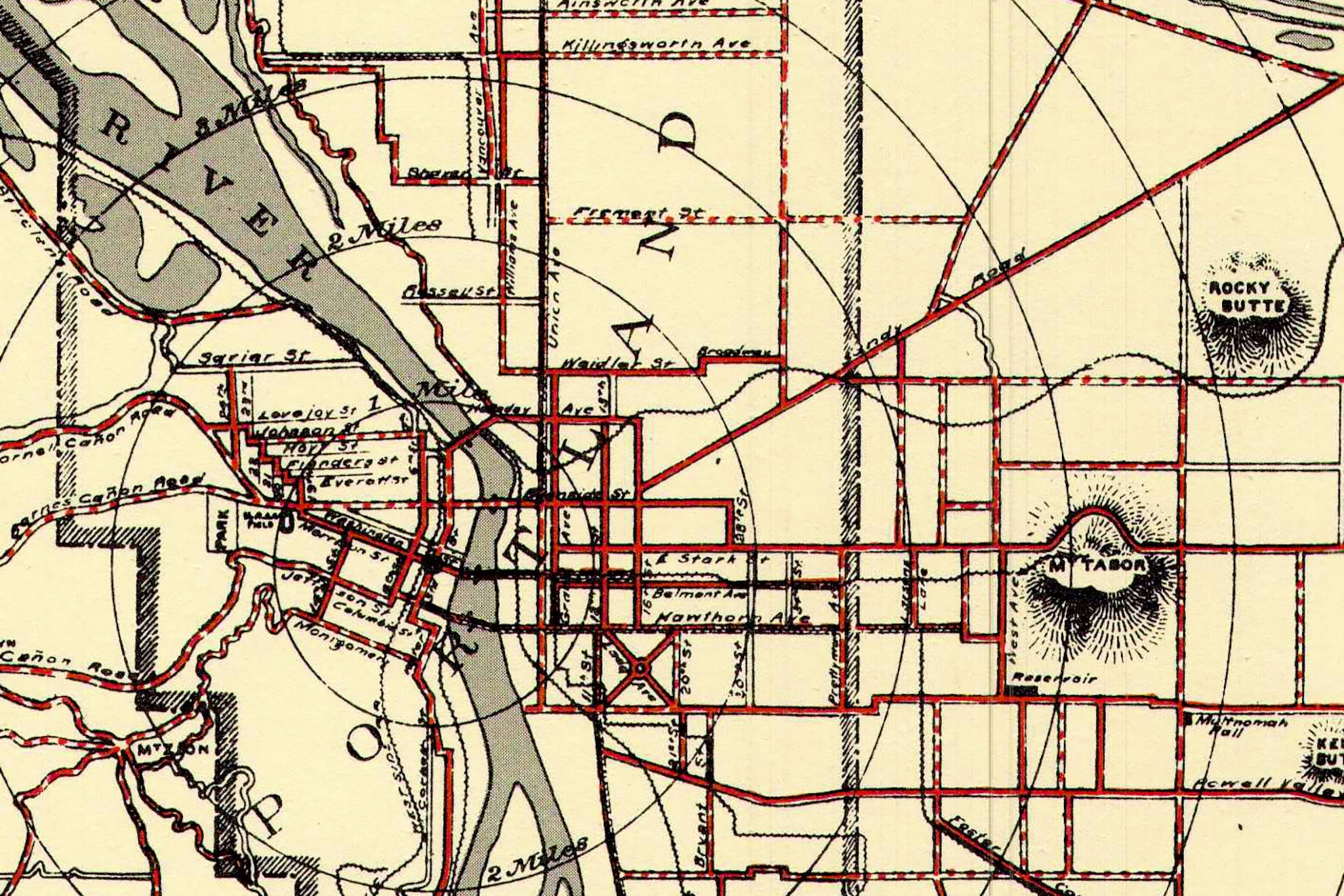

Portland had plenty of bike paths even back in 1896, as you can see in the map below. This 19th-century map is a source of inspiration for modern bike maps, says Matthew Hampton, senior cartographer for Metro, the regional government of Portland and its suburbs.

Hampton is currently working in his free time on a modern map using the same 19th-century styling. Like the older map, it will include taverns as well as bike routes. That creates a design challenge, however.

“The current density of taverns is overwhelming at its current scale,” Hampton says. He’s thinking of limiting it to brewpubs.

Most 19th-century bike maps were never intended to be cartographic works of art.

“The most common ones weren’t necessarily attractive,” says Friss. “Many of them were published by cycling clubs or bike manufacturers and used to promote cycling.”

Local clubs often published booklets, for example, that combined maps with step-by-step directions for various trips, along with advertisements for restaurants and other businesses along the way (not unlike the automobile tour guides of the early 20th century).

The cycling craze of the 1890s died out as suddenly as it started, but the rise of the automobile wasn’t the main reason, Friss says. He argues that it was more of a cultural shift: Cycling was a cool new thing that became less cool when more people started doing it.

“The hypermasculine men who adopted cycling as a sport early on began to see it as less sporting as more women began to ride,” Friss says. “The wealthy people who formed cycling clubs and organized fancy promenades began to see cycling as less exclusive as poorer people began to ride.”

The current enthusiasm for urban cycling seems to have some staying power, Friss says, but it may not last forever. The bike movement has been tied to a broader urban renaissance in the last two decades, but such social movements come and go, he says. If the desire for city living starts to wane, or if autonomous cars change the way people get around, bicycles may once again fall by the wayside.

“I’m excited about the current enthusiasm, but as an urban historian, I’m suspicious that in 20 or 30 years we’ll still be talking about bicycles the same way,” Friss says. “I hope I’m wrong.”