20 years after Katrina, New Orleanians are redefining 'home'

After one of the deadliest hurricanes in American history, many New Orleans residents faced a mountain of obstacles to rebuild. These are their stories.

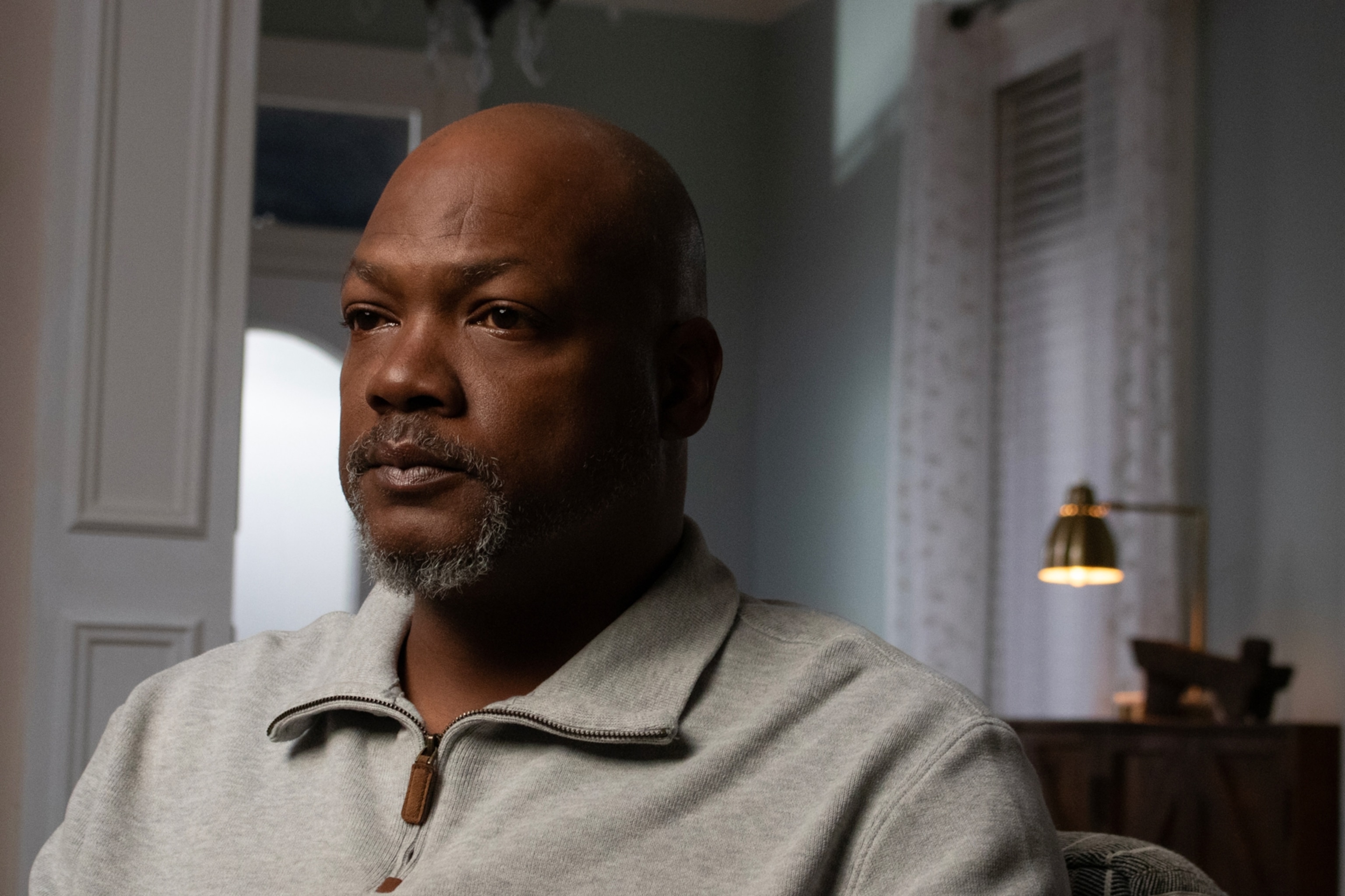

On August 28, 2005, the eve of Hurricane Katrina’s landfall, Shelton Alexander stood outside his home in St. Bernard Parish, a couple of miles away from Downtown New Orleans, as a storm warning echoed from a nearby radio. Katrina was gaining strength by the hour.

At that point, the poet and former Marine made sure his mother evacuated. But for himself, staying felt like the only option—a mix of necessity, responsibility, and quiet defiance in the face of a storm he knew would be unlike anything he’d seen before.

Nearly 1,900 people died as a result of Hurricane Katrina. More than 650,000 were displaced. And while some neighborhoods have rebuilt, others remain vacant of the lives that once lived there.

(Here's what made Hurricane Katrina one of the worst storms in U.S. history.)

Before that fateful storm, the city’s population stood at about 484,000. By July 2006, that number dropped to just over 230,000. Today, New Orleans has a population of about 351,399 that is steadily decreasing each year. The number of Black Americans residing in New Orleans has also declined from 67 percent in 2000 to 56 percent in 2024.

Ahead of the 20-year anniversary of the storm, Hurricane Katrina: Race Against Time, National Geographic’s five-part documentary series streaming on Disney+ starting July 28, offers an intimate look at Hurricane Katrina through the eyes of those who lived it. Below are two stories of the many, many survivors.

Residents neglected by their own city

As Katrina loomed off the Gulf Coast, Alexander made plans to evacuate temporarily to Baton Rouge. But when he realized he didn’t have enough gas, he rerouted to the Superdome—a shelter of last resort—navigating three feet of floodwater along the way.

“I was grabbing a crucifix, praying, ‘Lord, please let me get through it,’” he says. Along the way, he picked up 19 people who were also looking for shelter.

What he found at the Superdome was not relief, but neglect. “The National Guard was there, but nobody really was in charge,” says Alexander. “There were so many breakdowns of communication—it was chaos.”

(Read a detailed timeline of how the storm developed.)

Alexander brought with him a video camera—something he often used to capture his poems, stories, and thoughts. In the middle of that darkened dome, his footage became something else entirely: evidence.

“Without that video proof, a lot of people wouldn’t have believed my story,” he says.

There was no coordination of food, water, or medical aid, and no official word on what came next. Just tempers rising and the Louisiana summer heat pressing in from all sides.

“It was unbearable,” says Lynette Boutte, a resident of the Tremé neighborhood. She recalls how a group of men left the Superdome, discovered water trucks parked beneath a nearby bridge, and began distributing bottles to the crowd.

“When they started distributing, the only thing they said was, ‘Drink it—don’t waste it, because we don’t know how long it’ll last or when we’ll get out.’”

The fight to return home

When the waters receded a month later, a second crisis began. Recovery money flowed into New Orleans, but much of it bypassed the people who needed it most. Road Home, a federal relief program run by the Louisiana Recovery Authority, cheated people in poor neighborhoods while giving more to those in wealthy areas.

“It was November 2005 when I came back to the city,” Boutte, who went to Florida shortly after the storm hit to stay with a friend, says. “I didn’t get help from the state or the federal government. I became aggressive in my pursuit, because I realized, if you don’t take care of yourself, nobody else will.”

Boutte’s roots can be traced back to the 1800s in Tremé, one of the oldest Black neighborhoods in the United States.

“My parents built our family home in 1960, just before Hurricane Betsy,” she says. “That house is still there. My niece lives in it now—we sold it to her mother. My grandmother was born two doors away in 1903. Her siblings, too.”

When Boutte, a hairdresser, was ready to open her own beauty salon in 1995, she searched for a place close to her roots. She found a building just around the corner from her family’s place that had once been a ballroom turned grocery store, then a beauty salon in the 1950s. In the back, a small residence—added in the 1920s after the neighborhood’s first major flood—became her home.

Before Katrina, Boutte remembers a neighborhood full of community spirit. Walking from her mother's house, it was customary to stop and greet neighbors along the way, something she says has since faded. She also notes that the neighborhood no longer hosts community events.

In the aftermath of the hurricane, Boutte feels that city leaders prioritized tourism over the needs of residents. Instead of rebuilding for the community, she believes they used the disaster as an opportunity to push gentrification and reshape New Orleans for outsiders, essentially eliminating the neighborhood’s character.

“They’ve torn down these beautiful, old houses that lined Esplanade,” she says of a major neighborhood street. “Now, everything is gawky—they lost all their historic value.”

The New Orleans that Katrina left behind

For Alexander, returning wasn’t immediate. Not long after the storm hit, he headed west to California, where he found work alongside his father, a master carpenter.

Many New Orleans residents quickly found that rebuilding was out of reach—contractors overcharged or abandoned jobs, local labor was sidelined, and those without resources or connections were priced out of their own recovery.

“Me and my dad came back from California to help," Alexander says. "But they didn’t want local people doing the work. We were living in FEMA trailers, watching guys from out of state getting paid $35, $40 an hour just to sit in trucks. Locals like me—people who wanted to rebuild—could’ve used those jobs to invest in properties in our neighborhoods.”

Alexander watched the New Orleans he once knew and loved turn into a different place entirely.

“When I was growing up, neighborhoods like the Lower Ninth Ward and Seventh Ward were mostly African American,” says Alexander. “They were in locations close to hospitals and what people needed. After Katrina, they tore down the projects and replaced them with mixed-income housing. Most of the people who lived there before weren’t allowed back in.”

Boutte also watched homes disappear—not because they were damaged beyond repair, but because the people who owned them couldn’t afford to fight for them.

Like her neighbors, she is still approached by people offering to buy out her property for a higher price. “Like I told them, they can't get it from me,” she says.

The city that pulls you back

For years, it felt Alexander’s mother, who passed away shortly after he returned from California, was still tethering him to New Orleans. But in 2019, he felt like he had accomplished all he came back to the city to do—from renovating the trailer his late mother bought to hosting open mic nights in the city.

It was his mother’s voice in his head that pushed him to make his move to Texas. “As I was in reflection and prayer, I heard my mom say ‘You did all you can do, so it's time to move on. You could always come back home, you know, but don't sit here and be mourning for me.'"

Although Alexander left Louisiana for Texas, the city continues to leave its mark on him.

“I came for Good Friday this year,” he says. “I was supposed to stay two weeks. I stayed six. That’s the hold the city has on you.”

The trauma of Katrina still echoes through the streets of New Orleans, but so does the strength of its people—through Second Line Sundays, in the smell of red beans on Mondays, in the generations of families still rooted in place.

“I think in the next year, we're going to see another influx of people that left that’s going to be coming back after realizing there is no place like New Orleans,” Boutte says.

Nearly 20 years later, New Orleans is still healing, and its people are still returning.

“My mom used to say New Orleans is a boomerang,” Boutte says. “You come here, and trust me, you're coming back.”