Where is tornado alley? How the deadliest storm zone in the U.S. is shifting east

Scientists say a new epicenter is forming for the deadliest storm zone in the U.S. Here’s where people are now most at risk from tornadoes.

Tornadoes are some of the most destructive natural disasters seen in the United States each year, and twisters are 10 times more common in Tornado Alley.

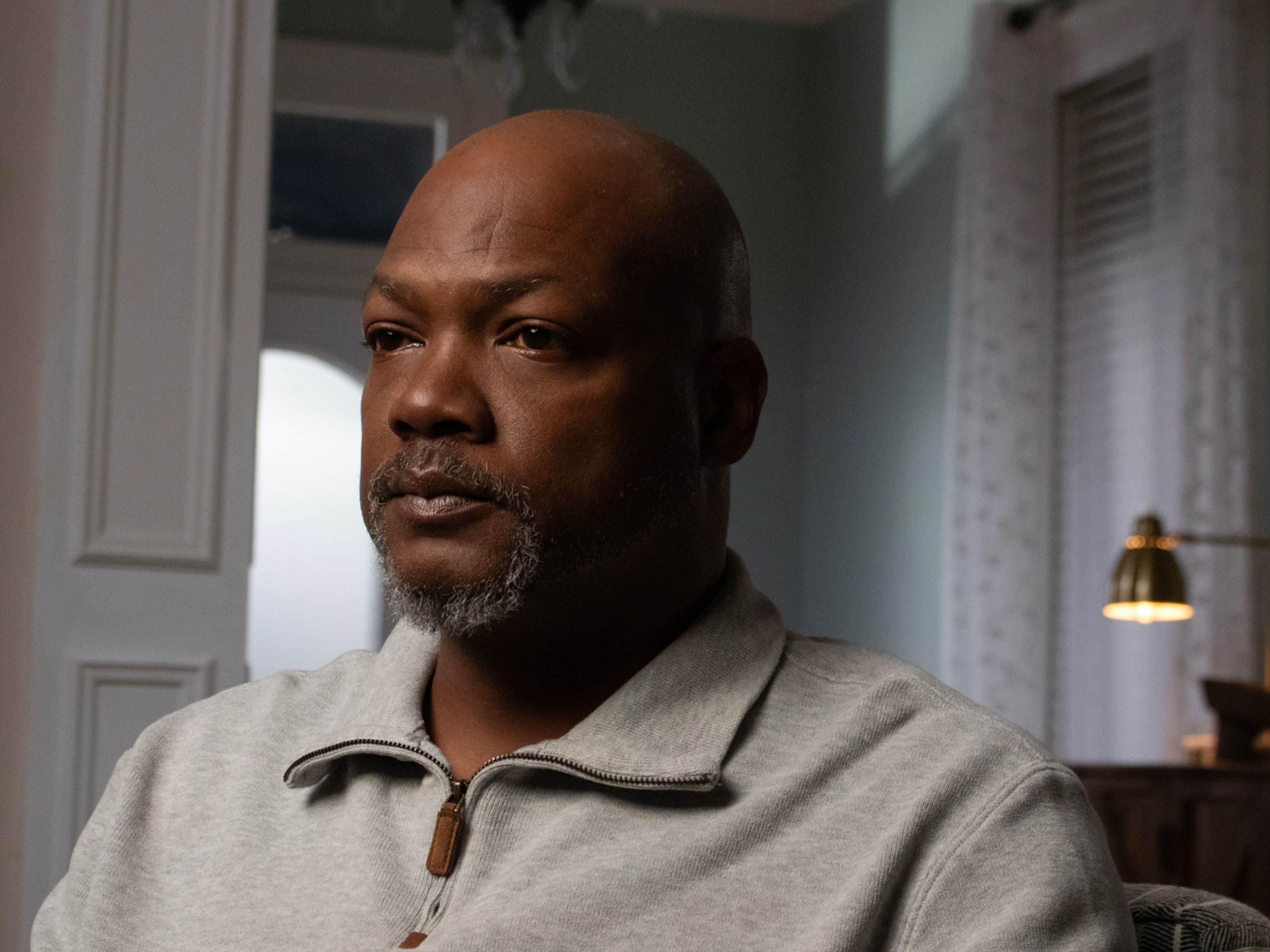

But for tornado expert Stephen Strader, the term Tornado Alley may be a bit outdated. “We've had devastating tornadoes outside of what people consider Tornado Alley,” the Villanova University associate professor explains. And the disastrous phenomenon is only expected to get worse.

Drier conditions in the Great Plains, coupled with increased moisture in the Southeast is shifting tornado activity away from states like Texas, Oklahoma, and Kansas. Scientists attribute this shift to the east to climate change.

“It’s a very subtle shift,” Strader says. Cities like Dallas and Austin, Texas, are seeing four fewer tornado days per decade, with an increase in tornado activity in places further east like Memphis, Tennessee.

Still, the shift is “notable,” says Jana Houser, associate geography professor at Ohio State University. “We are seeing places that are not expecting tornadoes become victims to tornadoes.”

In 2024, six different tornado outbreaks caused billions of dollars in damage each, many of which affected states outside of Tornado Alley, such as Florida, Louisiana, Arkansas, and Kentucky, to name a few.

Here’s what you should know about Tornado Alley and why the shift is impacting millions of Americans.

How do tornadoes form?

Strader compares the severe weather phenomenon to baking a cake.

“If you go into your cupboard, and you go into your fridge, and you pull out butter, you pull out sugar, and you set them on the counter, those are the ingredients you need to make a cake,” Strader explains. “For severe weather, we look for ingredients similarly, but those ingredients are related to the atmospheric conditions.”

Those ingredients include heat and moisture, drier air above the warm air, and wind shear, or changes in wind speed and direction that can create the rotation that forms a tornado, Strader says.

(Why these weather enthusiasts are storm chasing in Tornado Alley.)

The dry air high up in the atmosphere comes from the Rocky Mountains and forms what’s called a “cap” that slows or even prevents the development of a tornado, he adds.

“What we know is that as climate change continues to increase, that cap is getting stronger and stronger, which means that storms that used to occur in eastern Oklahoma may be now starting to occur in Central Arkansas,” Strader explains. “It basically means you're gonna have to bake your [cake] longer.”

What states are in Tornado Alley?

Tornado Alley spreads across much of the Great Plains and Midwest regions of the United States. Texas, Oklahoma, Kansas, and Nebraska, as well as parts of Colorado, New Mexico, Missouri, and Iowa feel the effects of the twisters that are common in the area.

In 1948, two Air Force officers tasked with monitoring severe weather in the Great Plains, correctly predicted a tornado would hit Oklahoma’s Tinker Air Force Base where they were stationed—marking the start of modern tornado warnings. Four years later, the same officers first used the term Tornado Alley to refer to the region of Texas, Colorado, Kansas, and Oklahoma where they tracked storms.

But even though its boundaries are shifting, experts say tornado alley as we know it isn't going away any time soon.

“We don't expect [traditional Tornado Alley to disappear], and that's because the ingredients that make severe weather tornadoes, the Rocky Mountains, and the Gulf of Mexico, are critical for that, and we're not going to remove those.”

The rising tornado risk in the Southeast

Because the Southeast region of the U.S. is historically less familiar with tornadoes, this eastern shift poses distinct risks for those in the area.

With a larger population than the Great Plains, the eastern half of the country is more likely to experience tornadoes in developed areas, where there’s an increased risk of property damage and fatalities. The region also has more trees that reduce visibility during storms, making it more difficult to see the path of a tornado and understand the immediate danger, Strader explains.

Night tornadoes are more frequent in states like Mississippi and Alabama. They are twice as deadly as tornadoes that take place during the day, in part because people are asleep and more likely to miss critical alerts. Between 1950 and 2019, 46 percent of Tennessee’s tornadoes occurred at night—more than any other state.

The region also has a large share of the nation’s mobile homes, which aren’t designed to withstand tornadoes and if damaged, may disproportionately affect low-income residents. Climate change increasing severe storms in the Southeast further exacerbates the threat of year-round tornadoes. Milder temperatures extend tornado season well into the winter months, especially in Southern states like Arkansas, Tennessee, Mississippi, and Alabama.

How much does climate change affect tornadoes?

Climate change is just one factor contributing to Tornado Alley’s deadly shift, Strader says. There’s also a significant societal element at play—population growth.

“The tornado that was in the middle of a field 50 years ago is not going through a field today. It's going through the middle of a brand-new subdivision,” Strader explains.

The growing U.S. population is an even bigger concern than climate change, Strader says. “That's scary to us, because that's like saying, ‘If we woke up in a world without climate change, we'd still have a growing tornado problem.’”

But climate change isn’t going anywhere, “so now what we have is this multiplicative effect,” Strader says. “Impacts aren't going up in a straight line. Impacts are exponentially growing.”

How to stay safe as tornado threats expand across the U.S.

If you’re home when a tornado strikes, find an interior room without windows on the lowest level, ideally a basement. You can also cover yourself with a mattress or a blanket for extra protection.

If you’re driving, get out of your car and look for a ditch or any low-lying area away from trees. Protect your head with your hands. Houser warns to never park your car under a bridge due to the increased wind speed.

Updating your emergency weather plans in case of a tornado is also best to keep your family safe.

“The number one thing that everyone can do is that if you live east of the Continental Divide, you should have a NOAA Weather Radio,” Strader says. These radios stay on 24/7 but only alert you during severe weather.

Tornado warning sirens were originally used to alert people to bomb raids during the Cold War, Strader explains. “They actually were never meant to be heard indoors, so you can't rely on them.”

Strader also encourages homeowners to build structures that are better able to withstand tornadoes. For manufactured homes, improving how they are secured to the ground will go a long way toward protecting you and your family. Experts recommend checking with your insurance company to see if your plan offers incentives for strengthening your home against natural disasters.

“The reality is that things are changing, and we need to anticipate those changes as a society in an effort to stay ahead of the vulnerabilities that we're introducing by [climate change],” Houser says.